A Narrative of Filipino Ambitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philippines Illustrated

The Philippines Illustrated A Visitors Guide & Fact Book By Graham Winter of www.philippineholiday.com Fig.1 & Fig 2. Apulit Island Beach, Palawan All photographs were taken by & are the property of the Author Images of Flower Island, Kubo Sa Dagat, Pandan Island & Fantasy Place supplied courtesy of the owners. CHAPTERS 1) History of The Philippines 2) Fast Facts: Politics & Political Parties Economy Trade & Business General Facts Tourist Information Social Statistics Population & People 3) Guide to the Regions 4) Cities Guide 5) Destinations Guide 6) Guide to The Best Tours 7) Hotels, accommodation & where to stay 8) Philippines Scuba Diving & Snorkelling. PADI Diving Courses 9) Art & Artists, Cultural Life & Museums 10) What to See, What to Do, Festival Calendar Shopping 11) Bars & Restaurants Guide. Filipino Cuisine Guide 12) Getting there & getting around 13) Guide to Girls 14) Scams, Cons & Rip-Offs 15) How to avoid petty crime 16) How to stay healthy. How to stay sane 17) Do’s & Don’ts 18) How to Get a Free Holiday 19) Essential items to bring with you. Advice to British Passport Holders 20) Volcanoes, Earthquakes, Disasters & The Dona Paz Incident 21) Residency, Retirement, Working & Doing Business, Property 22) Terrorism & Crime 23) Links 24) English-Tagalog, Language Guide. Native Languages & #s of speakers 25) Final Thoughts Appendices Listings: a) Govt.Departments. Who runs the country? b) 1630 hotels in the Philippines c) Universities d) Radio Stations e) Bus Companies f) Information on the Philippines Travel Tax g) Ferries information and schedules. Chapter 1) History of The Philippines The inhabitants are thought to have migrated to the Philippines from Borneo, Sumatra & Malaya 30,000 years ago. -

Appendix 7 Information and Data of Existing Outfall

Appendix 7 Information and Data of Existing Outfall Data Collection Survey for Sewerage Systems in West Metro Manila Outfall Location A Date Surveyed: 13 & 17 May 2016 City/Town: Las Pinas Weather: Fair - Cloudy - Rainy p p Notes: e n N1 - Water Depth (Full / PartlyFull) N6 - Water Color (Clear) N11 - with floating trash/garbage LPR - Las Pinas River Outfall Identification d N2 - Water Depth (Half) N7 - Water Color (Brown) U/S - upstream IC - Ilet Creek LP-OF000 i x N3 - Water Depth (Low / Below Half) N8 - Water Color (Dark/Murky) D/S - downstream 7 N4 - Water Flow (Stagnant) N9 - Water Odor (None) OF - outfall outfall N5 - Water Flow (Flowing) N10 - Water Odor (Foul) LP - Las Pinas number E City/Municipality x i s OUTFALL INFORMATION t i Coordinates Findings/Observations n Tributary g Main River UTM N (Latitude) E (Longitude) Other Remarks Photo Reference No. River/Waterway ID N1 N2 N3 N4 N6N5N7 N8 N9 N10 N11 N E Deg. Min. Sec. Deg. Min. Sec. O u 4.00m wide box culvert crossing t f Diego Cera Avenue, catchment area a Zapote River LP-OF1 1600478.96 281172.44 14 28 5.59 120 58 11.43 X X XXX - residential & commercial, on-going 4088, 4089 l l construction of sluiceway and bridge D/S of box culvert LP-OF2/LSP- 0.30m dia pipe culvert, no water Las Piñas River 1601179.76 282053.89 14 28 28.64 120 58 40.65 4091 OF003 flowing, catchment area - residential App7-1 LP-OF3/LSP- 0.30m dia pipe culvert, no water Las Piñas River 1601180.74 282046.71 14 28 28.67 120 58 40.41 4091 OF004 flowing, catchment area - residential 0.50m wide concrete box conduit located U/S of Pulang Lupa bridge, LP-OF4/LSP- Las Piñas River 1601159. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

Tourism Battlefields

distinctive story. Some of these sites are sacred and some are commemorating Tourism battlefields. More importantly, all of these places have contributed a sense of time, identity, and place to our understanding of Cavite as a whole. Tourism is travel for recreational, leisure or business purposes. The World Tourism Organization defines tourists as people "traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year Metro Tagaytay Growth Corridor for leisure, business and other purposes". It has become a popular global leisure “Metro Tagaytay” is one major growth corridor of the Province. This would activity. Tourism is important, and in some cases, vital for many countries. It include the Municipalities of Silang, Alfonso, Mendez, Amadeo, Indang, was recognized in the Manila Declaration on World Tourism of 1980 as "an Magallanes, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo (Bailen), Maragondon, Ternate and Tagaytay activity essential to the life of nations because of its direct effects on the social, City. These municipalities are also the areas with high potential for tourism cultural, educational and economic sectors of national societies and on their considering its desirable weather condition and proximity to Tagaytay City, the international relations. center of tourism in Cavite. The Philippines is a very blessed nation in terms of its natural attractions. Since Tagaytay City has its own identity as a popular tourist destination due to Similarly, Cavite abounds with great objects, and subjects, of culture and its cool environment and attractions, it would be utilized seemingly as a “lead history. It is the birthplace of a good number of Filipino heroes and it has an anchor” to tow its adjacent municipalities into prominence as well as a viable interesting range of sites associated with the Philippine Revolution of 1896. -

Old Street Names of Manila Several Streets of Manila Have Been Renamed Through the Years, Sometimes Without Regar

4/30/2016 Angkan ng Leon Mercado at Emiliana Sales Yahoo Groups Old Street Names of Manila Several streets of Manila have been renamed through the years, sometimes without regard to street names as signpost to history. For historian Ambeth Ocampo, old names of the streets of Manila , “in one way reaffirmed and enhanced our culture.” Former names of some streets in Binondo were mentioned by Jose Rizal in his novels. Calle Sacristia (now Ongpin street ) was the street where Rizal’s leading character Crisostomo Ibarra walked the old Tiniente back to his barracks. The house of rich Indio Don Capitan Tiago de los Santos was located in Calle Anloague (now Juan Luna). Only a century ago, the surrounding blocks of Malate and Ermita were traverse only by Calle Real (now M.H. del Pilar Street ) and Calle Nueva (now A Mabini Street ) that followed the curve of the Bay and led to Cavite ’s port. Today’s Roxas Boulevard was underwater then. Along the two main roads were houses and rice fields punctuated by the churches of Malate and Ermita and the military installations like Plaza Militar and Fort San Antonio Abad. After the FilipinoAmerican War, new streets were laid out following the Burnham Plan. In Malate for instance, streets were named after the US states that sent volunteers to crush Aguinaldo’s army. Today, those streets were renamed after Filipinos patriots some became key players in Aguinaldo’s government. It is fascinating to learn that Manila ’s rich heritage is reflected in its streets. Below is a list of current street names and the little history behind it: Andres Soriano Avenue in Intramuros was formerly called theAduana, after the Spanish custom house whose ruins stand on the street. -

Chapter 6. Economic Sector Agriculture

Chapter 6. Economic Sector Figure 6.1. Distribution of Agricultural and Non-Agricultural Area (Has) Province of Cavite: 2012 Agriculture 2nd District 3rd District 1st District 0.22% 1.18% 4th District Agriculture, as defined, is the science of cultivating land, producing crops and 0.27% 1.71% raising livestock; and these were among the agricultural activities that the Caviteño farm workers had been actively involved with. Furthermore, fishery is 5th District 8.10% also another major component of the agricultural sector wherein the province is home to numerous fishery activities providing livelihood to many Caviteños. As 6th District previously discussed, Cavite is now one of the most populous provinces in the 8.21% country and has achieved industrial growth, but despite the growing of many industrial establishments and industrial estates which have been or are being Non-Agricultural developed in various parts of the province, it is still considered agricultural and Area has a lot of potentials in the production of corn, coffee, vegetables and other 49.83% high value crops. 7th District 30.47% Based on the data gathered from the Office of the Provincial Agriculturist, the agricultural land is about 50.17% of the total land area of the province or 71,590.71 hectares while 49.83% or 71,115.29 hectares is non-agricultural area. Out of the agricultural area, 43,478.54 hectares or 30.47% came from 7th District, 8.21% or 11,717.71 hectares comprised 6th District, 5th District has 11,563.20 hectares or 8.10% while 2,445.56 hectares or 1.71% is from 4th District. -

Annual, 35 1St 35 Annual, 35 1St Packaging of Reports

Highlights Of Accomplishment Report CY 2014 Prepared by: Corporate Planning and Management Staff Table of Contents TRAFFIC DISCIPLINE OFFICE ……………….. 1 TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT Income from Traffic Fines Traffic Direction & Control; Metro Manila Traffic Ticketing System 60-Kph Speed Limit Enforcement Bus Management and Dispatch System Southwest Integrated Provincial Transport System (SWIPTS) E-Tagging for Public Utility Vehicles Enhance Bus Segregation System (EBSS) Anti-Illegal Parking Operations Enforcement of the Yellow Lane and Closed-Door Policy Anti-Jaywalking Operations EDSA Bicycle-Sharing Project Anti-Colorum and Out-of-Line Operations Operation of the TVR Redemption Facility Road Emergency Operations (Emergency Response and Roadside Clearing) Continuing Implementation of the Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) Monitoring of Field Personnel Other Traffic Management Measures implemented in 2014 TRAFFIC ENGINEERING Launching of the ITB-based Traffic Control System and Inauguration of the New Metrobase Building Design and Construction of Pedestrian Footbridges Geometric Improvement/ Road Widening Development of Bike Lanes Fabrication of Bike Shelters Application of Thermoplastic Pavement Markings Traffic Signal Operation and Maintenance Fabrication and Manufacturing/ Maintenance/ Installation of Traffic Road Signs/ Facilities Other TEC-TED Special Projects Other Traffic Improvement-Related/ Special Projects/ Activities Replacement of City Bus Stickers under the Enhanced Bus Segregation System -

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT for the Light Rail Transit Line 1 South Extension Project Volume 1

E1970 Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT for the Light Rail Transit Line 1 South Extension Project Public Disclosure Authorized Volume 1 Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted by Light Rail Transit Authority August 21, 2008 Public Disclosure Authorized i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . i Brief Description of the Project . i Brief Description of Data Gathering . ii Project Screening and Scoping . iii Brief Description of Project Environment . iii Physico-chemical Aspects . iv Biological Aspects . vii Socio-Economic Aspects . vii 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 1.1 Project Background . 2 1.2 EIA Approach and Methodology . 3 1.3 EIA Process Documentation . 12 1.4 EIA Team . 14 1.5 EIA Study Schedule . 15 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION . 16 2.1 Project Rationale . 17 2.2 Alternatives . 20 2.2.1 The Five (5) Basic Alternative Routes . 20 2.2.2 The Four (4) Short-Listed Alternative Routes . 23 2.2.3 Selection of Technically Preferred Route for North and Central Section . 33 2.3 Project Area and Location . 36 2.4 Project Description . 39 2.4.1 System Overview . 39 ii 2.4.2 Pre-Construction and Construction Phases . 72 2.4.3 Operational Phase . 97 3 BASELINE ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS . 99 3.1 Environmental Study Area . 100 3.2 Physical Environment . 100 3.2.1 Geomorphology . 100 3.2.2 Geology . .. 105 3.2.3 Statigraphy . 106 3.2.4 Seismicity . 107 3.2.5 Earthquake Generators . 109 3.2.6 Hazard Identification . 113 3.2.7 Surface Hydrology . 120 3.2.8 Land Use . 125 3.2.9 Pedology . 129 3.2.10 Water Quality and Limnolgy . -

28 SEPTEMBER 2020, MONDAY Headline STRATEGIC September 28, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 1 Opinion Page Feature Article

28 SEPTEMBER 2020, MONDAY Headline STRATEGIC September 28, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 1 Opinion Page Feature Article DENR suspends 2 Cebu dolomite firms ByEireene Jairee Gomez September 28, 2020 THE Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has suspended two dolomite firms in Alcoy, Cebu, pending results of an investigation of alleged coral reef damage, water quality monitoring and ambient air quality, the DENR chief said recently. This came after an inspection, led by DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu, who immediately called for the suspension of Dolomite Mining Corp. (DMC) for its quarry operations and Philippine Mining Service Corp. (PMSC), a processing plant for dolomite. He directed the DENR-Environmental Management Bureau in Region 7 to conduct a water-quality sampling in waters below the conveyor at the shiploading facility and conduct ambient air quality. He also ordered the Provincial Environment and Natural Resources-Cebu to conduct a coral assessment to determine the health condition of the corals that was the subject of the complaint by the provincial government. DMC, the only large-scale producer of dolomite materials, is a holder of a 25-year mineral production sharing agreement covering 524.6103 hectares of dolomite property, located within the municipalities of Alcoy and Dalaguete, Cebu, which will expire in 2030. PMSC is a holder of a mineral processing permit, which will expire in 2023. Source: https://www.manilatimes.net/2020/09/28/news/regions/denr-suspends-2-cebu- dolomite-firms/773052/ -

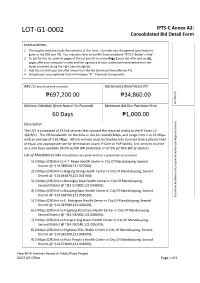

IPTS-C Annex A2: Consolidated Bid Detail Form

LOT-G1-0002 IPTS-C Annex A2: Consolidated Bid Detail Form Instructions: 1. Thoroughly read and study the contents of this form. Consider also the general specifications given in the BDS and ITB. You may also refer to the MS Excel workbook “IPTS-C Bidder’s Aide”. 2. To bid for this lot, print all pages of this lot and fill-in on the Page 1 your bid offer and on ALL pages affix your company’s name and the signature of your authorized representative in the boxes provided along the right hand margin(s). 3. Add this lot with your bid offer amount on the Bid Summary Sheet (Annex A1). 4. Include your accomplished form in Envelope "B" - Financial Components ABC (12-month service contract) Bid Security Bond Value (P) (P) ₱697,200.00 ₱34,860.00 Offer Delivery Schedule (from Notice-To-Proceed) Minimum Bid Doc Purchase Price Bid 60 Days ₱1,000.00 Description ) The LOT is composed of 23 link services that connect the required site(s) to the IP Core: L1- tative 1[A/B/C]. The CIR bandwidth for the links in this lot total 83 Mbps, and range from 2 to 23 Mbps with an average of 3.61 Mbps. All link services must be trunked into no more than 2 phycial links of equal and appropriate size for termination at any IP Core or PoP facility. Link services shall be on a 24H basis available 99.0% w/ NO BW protection or 97.9% w/ 50% BW protection. List of Mandatory Links (Coordinates are given without a guarantee of accuracy) 1) 2 Mbps (CIR) link to A.T. -

3Rd Quarter of 2014

Highlights Of Accomplishment Report 3rd Quarter of 2014 Prepared by: Corporate Planning and Management Staff Table of Contents TRAFFIC DISCIPLINE OFFICE ……………….. 1 TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT Income from Traffic Fines Traffic Direction & Control; Metro Manila Traffic Ticketing System 60-Kph Speed Limit Enforcement Bus Management and Dispatch System Southwest Integrated Provincial Transport System (SWIPTS) Anti-Illegal Parking Operations EDSA Bicycle-Sharing Project Anti-Jaywalking Operations Enforcement of the Yellow Lane and Closed-Door Policy Anti-Colorum and Out-of-Line Operations Operation of the TVR Redemption Facility Road Emergency Operations (Emergency Response and Roadside Clearing) Continuing Implementation of the Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) Monitoring of Field Personnel TRAFFIC ENGINEERING Design and Construction of Pedestrian Footbridges Application of Thermoplastic Pavement Markings Fabrication and Manufacturing/ Maintenance/ Installation of Traffic Road Signs/ Facilities Installation of Traffic Facilities and Road Signs Maintenance of Traffic Road Signs and Facilities Street Lighting Maintenace Traffic Signal Operation and Maintenance Other Special Projects TRAFFIC EDUCATION Other Traffic Improvement-Related/ Special Projects/ Activities Replacement of City Bus Stickers under the Enhanced Bus Segregation System (EBSS) Creation of Task Force Pantalan Creation of the Special Truck Lane Task Force METROBASE FLOOD CONTROL & SEWERAGE MANAGEMENT OFFICE (FCSMO) ……………….. 17 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT -

100 Significant Events in Philippine History

100 significant events in Philippine history Philippine history is made up of thousands of events that happened from the earliest period ever documented to the present. This list includes only 100 major events that influenced Philippine history from the 14th century to the end of the 20th century. Interestingly, the events included on this list represent major areas where the life of the nation revolves like trade and commerce, religion, culture, literature and arts, education, various movements, wars and revolutions, laws and government, and military. Moreover, the events mentioned here are crucial in understanding the present and future of the Philippines as a nation. 1. Trading with the Chinese. 10th century. They dominated Philippine commerce from then on. 2. Arrival of Arab traders and missionaries. Mid-14th century. They conducted trade and preached Islam in Sulu that later spread to other parts of the country. 3. Arrival of Ferdinand Magellan. March 1521. It marked the beginning of Spanish interest in the Philippines as several Spanish expeditions followed. 4. First Mass in the Philippines. March 31, 1521. It was held in Limasawa, an island in Southern Leyte. Symbolized the conversion of many Filipinos to Roman Catholicism. 5. Death of Ferdinand Magellan. April 27, 1521. 6. Landing of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in Cebu. 1565. This marked the beginning of Spanish dominion in the Philippines as Legazpi later established the seat of Spanish colonial government in Manila. 7. Blood Compact. March 1565. Spanish Captain General Legazpi and Rajah Sikatuna performed the blood compact in Bohol as a sign of peace agreement between their parties.