Correspondence and Media Coverage of Interest Between January 26, 2021 and February 4, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

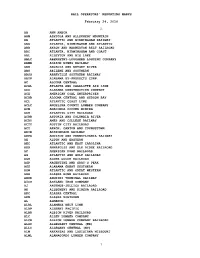

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

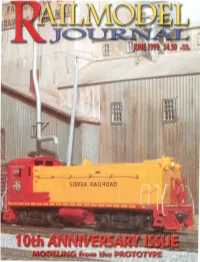

Sierra Rail Oad 000

SIERRA RAIL OAD 000 Earty EMD production without Dynamic Brakes. Deliveryto stores In late May/earty June. Roadname/ltem # Paint Scheme/Road No. Paint Scheme/Road No. Canadian National CN North America/GTW Burlington Northern Green and Black Milwaukee Road Orange and Black #37-2801 5931 #37-2701 6333 #37-2708 149 #37-2802 5934 #37-2702 6363 #37-2709 160 Missouri Pacific Norfolk Southern Black Yellow and Gray/GTW Chicago & North Western Falcon Service #37-2803 3108 #37-2703 6910 #37-2710 6139 Soo Line Red and White #37-2704 6922 #37-2711 6142 #37-2804 759 CSX New Image Union Pacific "We Can Handle It" #37-2805 787 #37-2705 8186 #37-2712 3220 Union Pacific Yellow and Gray/Large Number #37-2706 8204 #37-2713 3342 #37-2804 759 EMD Leasing Supplied with both versions of brake housings #37-2805 787 #37-2707 f 111.11K:.A.TO I TE PIE The needAztek A4709 is a mastercomplete tools. (WEATHERING) The Aztek A4709 Set airbrush set that includes everything you need to per includes: A470 Airbrush fect a full range of effects... without time-consuming, and 15'(4.5m) hose; Fine (AUTHENTIC LOOK) complex needle adjustments. Move from fine detail to Line Nozzle/.30Illm; General Purpose Nozzle/.401ll1ll; broad application railroad scenery simply by installing High Flow Nozzle/.50Illm; Medium Cover Nozzle/.70mm; a different nozzle ... change colors in less than 30 sec 2.5cc Side Feed Color Cup; 3cc Gravity Feed Color Cup; onds. This easy to use, easy to clean system 7.5cc Gravity Feed Color Cup; lOcc Gravity Feed Color works as both a single- or double Cup; 28mm Siphon Cap and Bottle; 33ml11 Siphon Cap action airbrush. -

Yosemite Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Yosemite National Park California December 2016 Foundation Document k e k e e r e C r Upper C n Yosemite o h y c r Fall n k A a e C e l r Yosemite Point a n C 6936ft y a Lower o 2114m i North Dome e d R t 7525ft i Yosemite n I 2294m m Fall e s ek o re Y U.S. Yosemite Valley Visitor Center C ya Court a Wilderness Center n e Museum Royal Arch T Lower Yosemite Medical Clinic Cascade Fall Trail Washington Columbia YOSEMITE Column Mirror Rock VILLAGE ROYAL Eagle Lake T ARCHES 4094ft Peak H 1248m 7779ft R The Ahwahnee Half Dome 2371m Sentinel Visitor E 8836ft Bridge Parking E North 2693m B Housekeeping Pines Camp 4 R Yosemite Camp Lower O Lodge Pines Chapel Stoneman T Bridge Middle H LeConte Brother E Memorial Road open ONLY to R Lodge pedestrians, bicycles, Ribbon S Visitor Parking and vehicles with Fall Swinging Bridge Curry Village Upper wheelchair emblem Pines Lower placards Sentinel Little Yosemite Valley El Capitan Brother Beach Trailhead for Moran 7569ft Four Mile Trail (summer only) R Point Staircase Mt Broderick i 2307m Trailhead 6706ft 6100 ft b Falls Horse Tail Parking 1859m b 2044m o Fall Trailhead for Vernal n Fall, Nevada Fall, and Glacier Point El Capitan Vernal C 7214 ft Nature Center John Muir Trail r S e e 2199 m at Happy Isles Fall Liberty Cap e n r k t 5044ft 7076ft ve i 4035ft Grizzly Emerald Ri n rced e 1230m 1538m 2157m Me l Peak Pool Silver C Northside Drive ive re Sentinel Apron Dr e North one-way Cathedral k El Capitan e Falls 0 0.5 Kilometer -

The Greening of Paradise Valley

The Greening of Paradise Valley The first 100 years (1887-1987) of the Modesto Irrigation District By Dwight H. Barnes Commissioned by the Modesto Irrigation District In recognition of its centennial year Dedication In the span of recorded history, the story of the San Joaquin Valley and that portion of it served by the Modesto Irrigation District is quite brief. The impact of a region upon a nation, however, cannot be measured by time alone. Settled by adventurous, innovative, courageous people who had the vision and determination to change a huge valley which was desert waste in the summer and whose flood-swollen rivers ran 10 miles wide in the spring, the San Joaquin Valley today is the nation’s most productive agricultural region. This was the home of people such as Irwin S. Wright, who in 1868 invented jerk-line control of long pulling teams; of Benjamin Holt, inventor of the Caterpillar tractor who subsequently made possible the first army tanks; of George Stockton Berry, who, starting with a discarded portable steam engine, built the first mechanically-driven combine to harvest, thresh and sack wheat in a single operation, and of political and military leaders such as John C. Fremont, the first presidential nominee of the Republican Party, and famed General William Tecumseh Sherman. It was in this region that the farm cooperative received its greatest stimulus, resulting in the development of the world’s largest cooperatives such as the Milk Producers Association of California and Tri/Valley Growers, both of which were founded in Modesto. More than a century ago, enterprising leaders of this caliber envisioned the rich potential of the region’s agriculture; needed was a practical means of bringing water to the land throughout the summer months. -

M.M. O'shaughnessy Photograph Collection, Circa 1885-1986 (Bulk 1890-1934)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/k6mg7pb7 Online items available Finding Aid to the M.M. O'Shaughnessy photograph collection, circa 1885-1986 (bulk 1890-1934) Chris McDonald and Lori Hines The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. BANC PIC 1992.058 1 Finding Aid to the M.M. O'Shaughnessy photograph collection, circa 1885-1986 (bulk 1890-1934) Collection number: BANC PIC 1992.058 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Chris McDonald and Lori Hines Date Completed: 2007 Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: M.M. O'Shaughnessy photograph collection Date (inclusive): circa 1885-1986 Date (bulk): 1890-1934 Collection Number: BANC PIC 1992.058 Extent: 9 cartons, 10 volumes, 4 oversize boxes, 8 oversize folders, 6 boxes (negatives), 2 sleeves (strip negatives), 1 object90 digital objects (91 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: The M.M. (Michael Maurice) O’Shaughnessy photograph collection, 1887-1986, consists of photographic prints, film negatives, reports, albums, cartoons, lantern slides and ephemera relating to M.M. -

Roots of Motive Power

Roots of Motive Power Complete List of Titles Subjects Author Title <aA Feasibility Study :Redwood Logging M <Modern Sawmill Techniques, Vol. 5 Barber, H. H. <Our First Five Decades - The Story of the Park, Kenneth F. <Principles of Modern Excavation and Equi Morrison Knudsen Company 177 Days - Northwestern Pacific Railroad Anonymous 1937 Logging Ramsey, Dan 1948 Diamond T Truck - Owned By Seabisc 21st. Oregon Logging Conference and Logg A Feasibility Study: Redwood Logging Muse Cook, Margarite A Glance Back Anonymous A Pioneer Lumberman's Story Anonymous A Review of Harvesting Redwoods Chappell, Gordon A Short History of Steam Trains Over Cumb A.W. Davis Supply Company Anonymous Adams Motor Grader Maintenance Manual Anonymous Adlake Trimmings Beebe, Lucius Age of Steam, The J. I. Case Threshing Machine Co. Agitator is Thresher King Davidson, J. Brownlee Agricultural Engineering Davidson, J. Brownlee Agricultural Machinery Hawkins, N. Aids to Engineers' Examinations Anonymous Ain't No More Jones, Fred L. Air Brake Manual Kirkman, Marshall M. Air Brake: Construction and Working Williams, A. N. Air Brakes and Railway Signals Anonymous Air Compressors, 3-CD, 3-CDB & 3-CDC Cummins Engine Co. Air For Your Engine Anonymous Alaska Highway 1942 - 1992 Clymer, Floyd Album Of Historical Steam Traction Engines Anonymous Alco Domestic Parts Price Book Anonymous Alco Locomotive Renewal Parts Anonymous Alco Parts List Anonymous Alco Renewal-Parts Catalog Anonymous Alco Renewal-Parts Catalog, DRP-306 Anonymous Alco Staybolts Anonymous Alco Staybolts Bulletin No. 2011 Anonymous Alco Tool Catalog for Road & Switching Loc Yenne, Bill All Aboard! White, Ron All Kinds of Trains Allis - Chalmers Allis Chalmers Manufacturing Co. -

Michael Maurice) O'shaughnessy Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb5d5nb6sr Online items available Finding Aid to the M.M. (Michael Maurice) O'Shaughnessy papers Finding Aid written by Mary L. Morganti, in memory of Archivist, Linda Jordan, 1952-2001. Funding for processing this collection was provided by George A. Miller. The Bancroft Library © 2005 The Bancroft Library University of California Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library Finding Aid to the M.M. (Michael BANC MSS 92/808 c 1 Maurice) O'Shaughnessy papers Language of Material: Italian Contributing Institution: The Bancroft Library Title: M.M. (Michael Maurice) O'Shaughnessy papers creator: O'Shaughnessy, M. M. (Michael Maurice), 1864-1934 Identifier/Call Number: BANC MSS 92/808 c Physical Description: 125 linear feet20 boxes, 54 cartons, 42 volumes, 5 oversize boxes, 154 oversize folders, 52 tubes Date (inclusive): 1882-1937 Abstract: The M. M. (Michael Maurice) O'Shaughnessy papers, 1882-1937, consist of materials relating to his career as a civil engineer, working first as a consultant in private practice, and later as City Engineer of San Francisco. The collection contains primary and secondary source materials both created and collected by O'Shaughnessy in the course of planning, conducting, and overseeing a large range of engineering projects, and later kept as part of his own private files. His writings include typescripts and published versions of many speeches, articles, and books by O'Shaughnessy—both in his role as City Engineer, and as a consulting engineer who was active at the national and local level in professional organizations and societies. -

Railroads and the National Parks Presents an Excellent Discussion of the Importance of Railroads to the Establishment and Promotion of the National Parks in the West

RAILROADS IN THE NATIONAL PARKS William B. Butler Background Railroads were associated with the National Parks even before the Park Service was formally established in 1916. Although not yet a National Park, Hot Springs in Arkansas was set aside as a reservation in 1832 and the “Diamond Jim Line” was built between Malvern and Hot Springs in 1875 to bring tourists to the attraction; the reservation became a National Park in 1921. On a somewhat grander scale, the Northern Pacific completed a branch line – “the Park Branch” – in 1883 from Livingston to Cinnabar, Montana, to bring tourists to Yellowstone National Park. The railroad became an ardent supporter of the nation’s first National Park (1872) and promoted it widely to the pubic such as in the booklet Wonderland 1904 by the Northern Pacific’s director of advertising and historian, Olin Wheeler. Like the railroads to Yellowstone, the main line of the Great Northern across the northern United States was built just south of Glacier National Park in 1893, and the railroad promoted visitation and constructed several lodging facilities including the Many Glaciers Hotel. A subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway constructed a line from Williams, Arizona, to the south rim of the Grand Canyon in 1901, and to accommodate travelers, the railroad (through the Fred Harvey Company) built the El Tovar Hotel in 1905. Realizing that National Parks were becoming a great attraction for the public – and thus generating revenue producing passengers – the AT&SF then successfully led the lobbying effort to establish Grand Canyon National Park (1919). -

Sierra Railway Shops

NPS Form 10 900 OMB Control No. 1024 0018 expiration date 03/31/2022 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Sierra Railway Shops Historic District____DRAFT____ Other names/site number: ____Sierra Railway Jamestown Shops, Railtown 1897 SHP_____ Name of related multiple property listing:______________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing__________________ 2. Location Street & number: __18115 5th Avenue_____________________ City or town: __Jamestown____ State: __California_____ County: _Tuolumne______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ______________________________________________________________ ______________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places -

Newsletter Spring 2020 in Memoriam Betty Himoto

Newsletter Spring 2020 IN THIS ISSUE: COVID-19 Results in In Memoriam Program Postponement 1 In Memoriam 1 Postponement of Programs Betty Himoto Betty Himoto Railroad Scholarship Fund 2 Using an abundance of caution and to protect our Where Are They Now? 3 members and the community, we are postponing Locomotive #1000 all tours, presentations, and our upcoming Annual Oceano Depot Tour 3 Dinner Gala until further notice. We will continue to monitor guidance from local, national, and Female Railroad Directors 4 world health organizations and officials and will reschedule when it is safe to do so. UPCOMING EVENTS: In the meantime we are continuing to work remotely researching new articles for upcoming Friends Annual Dinner Gala The Santa Maria Valley Railroad Santa Maria Fairpark newsletters and planning future events. We are POSTPONED announced the passing of Director also performing research for several projects, Betty Chiyoko Himoto on Friends Presentation designing future exhibits, etc. So even though our "Heart of the Valley Talks" Wednesday January 22, 2020 at in Shepard Hall at the member activities are postponed, we continue to the age of 95. She was described Santa Maria Public Library work behind the scenes. We encourage all of you as a tireless advocate for rail POSTPONED to continue to support the Friends and renew your transportation on the Central Coast Annual BBQ at SMVRR Friends membership if you have not done so yet. and an unwavering supporter of Saturday, August 22, 2020 reinvestment for the company. 11 am to 3 pm The Santa Maria Valley Railroad asks that we convey to all of our members and the general The Santa Maria Valley Railroad public that the railroad continues to fully operate was purchased by the Coast Belle and is making every effort to keep their Rail Corp from the descendants of the Hancock Family on October 1, employees healthy and the trains running. -

Paradise Regained

Paradise Regained SOLUTIONS FOR RESTORING YOSEMITE’S HETCH HETCHY VALLEY Paradise Regained SOLUTIONS FOR RESTORING YOSEMITE’S HETCH HETCHY VALLEY AUTHORS Spreck Rosekrans Nancy E. Ryan Ann H. Hayden Thomas J. Graff John M. Balbus Cover image: Composite created using digital panorama photography and 3D animation software. Photo and composite by Greg Richardson, Level Par. Our mission Environmental Defense is dedicated to protecting the environmental rights of all people, including the right to clean air, clean water, healthy food and flourishing ecosystems. Guided by science, we work to create practical solutions that win last- ing political, economic and social support because they are nonpartisan, cost- effective and fair. ©2004 Environmental Defense Printed on paper that is 80% recycled, 80% post-consumer, processed chlorine free (text); 100% recycled, 50% post-consumer, processed chlorine free (cover). The complete report is available online at www.environmentaldefense.org. Contents Foreword iv CHAPTER 9 Impact of restoration on Acknowledgments v hydropower production and revenues 68 About the authors vi CHAPTER 10 Executive summary vii Water and power replacement costs 86 CHAPTER 11 CHAPTER 1 Introduction 1 Legal status and institutional considerations 94 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 12 Hetch Hetchy: past, present 5 Conclusion and recommendations 106 and future Glossary of technical terms 110 CHAPTER 3 California water summary 13 Acronyms 112 CHAPTER 4 Notes 113 California power summary 22 APPENDIX A CHAPTER 5 Summary of technial analyses The Tuolumne River and 30 Hetch Hetchy Reservoir alternatives Bay Area water system (Schlumberger Water Services) CHAPTER 6 APPENDIX B Alternative water-system 42 Water quality evaluation for Hetch components Hetchy Reservoir alternatives (Eisenberg, Olivieri & Associates) CHAPTER 7 Equivalent water-supply reliability 49 APPENDIX C Memorandum: Hetch Hetchy water CHAPTER 8 and power issues Water-quality analysis 62 (Somach, Simmons & Dunn) iii Foreword Douglas P. -

Hetch Hetchy: to Drain Or Not to Drain Brian E

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 2006 Hetch Hetchy: To Drain or Not to Drain Brian E. Gray UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian E. Gray, Hetch Hetchy: To Drain or Not to Drain, 57 Hastings L.J. 1261 (2006). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/194 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Gray Brian Author: Brian E. Gray Source: Hastings Law Journal Citation: 57 Hastings L.J. 1261 (2006). Title: Hetch Hetchy: To Drain or Not to Drain Originally published in HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL. This article is reprinted with permission from HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL and University of California, Hastings College of the Law. Hetch Hetchy: To Drain or Not to Drain Moderator PROF. BRIAN GRAY, U.C. HASTINGS COLLEGE OF THE LAW Panelists DAVID BEHAR, SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION HEATHER DEMPSEY, TUOLUMNE RIVER TRUST RON GOOD, RESTORE HETCH HETCHY RAY MCDEVITT, HANSON BRIDGETr MARCUS VLAHOS RUDY, LLP GRAY: I'd like to introduce our four panelists: Ron Good, from Restore Hetch Hetchy'; David Behar, from the City of San Francisco; Heather Dempsey, from Tuolumne River Trust; and Ray McDevitt, from the Bay Area Water Supply & Conservation Agency.