The Greening of Paradise Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instructionally Related Activities Report

Instructionally Related Activities Report Linda O’Hirok, ESRM ESRM 463 Water Resources Management Owens Valley Field Trip, March 4-6, 2016 th And 5 Annual Water Symposium, April 25, 2016 DESCRIPTION OF THE ACTIVITY; The students in ESRM 463 Water Resources Management participated in a three-day field trip (March 4-6, 2016) to the Owens Valley to explore the environmental and social impacts of the City of Los Angeles (LA DWP) extraction and transportation of water via the LA Aqueduct to that city. The trip included visiting Owens Lake, the Owens Valley Visitor Center, Lower Owens Restoration Project (LORP), LA DWP Owens River Diversion, Alabama Gates, Southern California Edison Rush Creek Power Plant, Mono Lake and Visitor Center, June Mountain, Rush Creek Restoration, and the Bishop Paiute Reservation Restoration Ponds and Visitor Center. In preparation for the field trip, students received lectures, read their textbook, and watched the film Cadillac Desert about the history of the City of Los Angeles, its explosive population growth in the late 1800’s, and need to secure reliable sources of water. The class also received a summary of the history of water exploitation in the Owens Valley and Field Guide. For example, in 1900, William Mulholland, Chief Engineer for the City of Los Angeles, identified the Owens River, which drains the Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains, as a reliable source of water to support Los Angeles’ growing population. To secure the water rights, Los Angeles secretly purchased much of the land in the Owens Valley. In 1913, the City of Los Angeles completed the construction of the 223 mile, gravity-flow, Los Angeles Aqueduct that delivered Owens River water to Los Angeles. -

May 16-31, 1970

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/16/1970 A Appendix “A” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/17/1970 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/18/1970 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/22/1970 A Appendix “C” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/24/1970 A Appendix “A” 6 Memo From Office of Stephen Bull – Appendix 5/26/1970 A “C” OPEN 6/2013 7 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/28/1970 A Appendix “F” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-5 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary May 16, 1970 – May 31, 1970 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

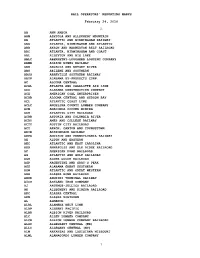

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Enhancing Environmental Flows of Putah Creek for Chinook Salmon Reproductive Requirements

Enhancing environmental flows of Putah Creek for Chinook salmon reproductive requirements Written by: Chan, Brian; Jasper, Chris Reynolds; Stott, Haley Kathryn UC Davis, California ESM 122, Water Science and Management, Section: A02 Abstract: Putah creek, like many of California’s rivers and streams, is highly altered by anthropogenic actions and historically supported large populations of resident and anadromous native fish species. Now its ecosystem dynamics have changed drastically with the Monticello dam, the Solano diversion canal and the leveeing of its banks. Over time the creek has found a balance of habitats for native and non-native fish species that is mainly dictated by species-preferred temperature tolerances (Keirman et. al. 2012). Cooler temperatures and faster flows upstream from Davis prove to be ideal habitats for native species, in particular, the federally endangered Chinook salmon, which is the most widely distributed and most numerous run occurring in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and their tributaries. As water moves downstream, it becomes shallower and warmer, resulting in ideal conditions for non-native species (Winters, 2005). This report analyzes the environmental flows released into putah creek and how much salmon preferred breeding habitat is available from this flow regime based on temperature. Introduction: Figure 1: Teale GIS Solutions Group (1999), US Census Bureau (2002), USGS (1993) [within Winters, 2005] The Putah Creek watershed is an important aspect in the natural, social, and economic livelihoods of the people of Yolo and Solano counties. The Putah Creek watershed begins at the highest point in Lake County, Cobb Mountain, and flows down to the Central Valley where it empties into the Yolo Bypass at near sea level. -

UC Davis Books

UC Davis Books Title Checklist of Reports Published in the Appendices to the Journals of the California Legislature 1850-1970 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5wj2k3z4 Author Stratford, Juri Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Checklist of Reports Published in the Appendices to the Journals of the California Legislature 1850-1970 Revised Edition 2018 Juri Stratford Copyright © 2016, 2018 Juri Stratford 2 Introduction The California Legislature published reports in the Appendices to the Journals from 1850 to 1970. The present Checklist covers the reports published in the Appendices to the Journals from 1850 to 1970. The Checklist is arranged by volume. The Appendices include reports produced by California executive agencies as well as the California Legislature. In a few instances, the reports include work by the United States federal government or the University of California. Each entry gives the volume number for the report in one of two formats: 1909(38th)(1) This first example indicates Appendix to the 1909 Journals, Volume 1, 38th session. The Legislature stopped assigning session numbers after the 57th session, 1947. For later years, the Appendices were published as separate series of Senate and Assembly volumes. For some years, only Senate volumes were published. 1955(S)(1) This second example indicates Appendix to the 1955 Senate Journals, Volume 1. 3 4 1850(1st)(Journal of the Legislature) McDougall, Lieut. Governor and President, &c.. [G] 1850(1st)(Journal of the Legislature) Special Report of Mr. -

Eocene Origin of Owens Valley, California

geosciences Article Eocene Origin of Owens Valley, California Francis J. Sousa College of Earth, Oceans, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; [email protected] Received: 22 March 2019; Accepted: 26 April 2019; Published: 28 April 2019 Abstract: Bedrock (U-Th)/He data reveal an Eocene exhumation difference greater than four kilometers athwart Owens Valley, California near the Alabama Hills. This difference is localized at the eastern fault-bound edge of the valley between the Owens Valley Fault and the Inyo-White Mountains Fault. Time-temperature modeling of published data reveal a major phase of tectonic activity from 55 to 50 Ma that was of a magnitude equivalent to the total modern bedrock relief of Owens Valley. Exhumation was likely accommodated by one or both of the Owens Valley and Inyo-White Mountains faults, requiring an Eocene structural origin of Owens Valley 30 to 40 million years earlier than previously estimated. This analysis highlights the importance of constraining the initial and boundary conditions of geologic models and exemplifies that this task becomes increasingly difficult deeper in geologic time. Keywords: low-temperature thermochronology; western US tectonics; quantitative thermochronologic modeling 1. Introduction The accuracy of initial and boundary conditions is critical to the development of realistic models of geologic systems. These conditions are often controlled by pre-existing features such as geologic structures and elements of topographic relief. Features can develop under one tectono-climatic regime and persist on geologic time scales, often controlling later geologic evolution by imposing initial and boundary conditions through mechanisms such as the structural reactivation of faults and geomorphic inheritance of landscapes (e.g., [1,2]). -

Geologic Features and Ground-Water Storage Capacity of the Sacramento Valley California

Geologic Features and Ground-Water Storage Capacity of the Sacramento Valley California By F. H. OLMSTED and G. H. DAVIS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1497 Prepared in cooperation with the California Department of ff^ater Resources UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director Tlie TT.S. Geological Survey Library catalog card for this publication appears after page 241. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract___________________________________________________ -_ 1 Introduction.-.--- .___-___________-___._--.______-----_ 5 Purpose and scope of the investigation.__________________ ______ 5 Location of area__-__-________-____________-_-___-_-__--____-_- 6 Development of ground water___________________-___-__ ___ __ 7 Acknowledgments....-------- ____________ _________________ 8 Well-numbering system..________________________________ _ 9 Geology--__--_--_--__----_--_-----____----_ --_ ___-__-- 10 Geomorphology_____________________________________________ 10 General features _______________________________________ 10 Mountainous region east of the Sacramento Valley...__________ 11 Sierra Nevada_______________________________________ 11 Cascade Range.._____________________-__--_-__-_---- 13 Plains and foothill region on the east side of the Sacramento Valley..__-_________-_.-____.___________ 14 Dissected alluvial uplands west of the Sierra -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

Klipsun Magazine, 2013, Volume 43, Issue 04 - Winter

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Klipsun Magazine Western Student Publications Winter 2013 Klipsun Magazine, 2013, Volume 43, Issue 04 - Winter Branden Griffith Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/klipsun_magazine Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Griffith, anden,Br "Klipsun Magazine, 2013, Volume 43, Issue 04 - Winter" (2013). Klipsun Magazine. 153. https://cedar.wwu.edu/klipsun_magazine/153 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Klipsun Magazine by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KLIPSUNRISE | WINTER 2013 On Ice Takedowns, Strikes and Submissions Earth Rise Experiencing the ultimate thrill sport Life behind the gloves Rediscovering our home planet DEAR READER, Klipsun is an independent student publication of Western Washington University EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Branden Griffith MANAGING EDITOR Lani Farley COPY EDITOR Lisa Remy STORY EDITORS Olivia Henry Chelsea Poppe Lauren Simmons LEAD DESIGNER Julien Guay-Binion DESIGNERS Adam Bussing Kinsey Davis PHOTO EDITOR Brooke Warren Photo by Brooke Warren PHOTOGRAPHERS Brooke Warren Mindon Win ime to come clean. I’m afraid of flying. This issue of Klipsun tells the tale of the man who helped ONLINE EDITOR Unfortunately, I didn’t know this until the us discover Earth through a photo, and why owning solar Elyse Tan airplane I was on started taxiing down the panels in a state known for rain isn’t a terrible idea. runway, preparing to take me and my family to People stronger than I, the 15-year-old kid sweating WRITERS the happiest place on Earth: Disneyland. -

Council Enters Into Historic Community Workforce Agreement with UCSF, Creating 1,000 Long-Term Construction Jobs

121th Year OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION TRADES COUNCIL OF SAN FRANCISCO Volume 121, No. 2 February 2021 www.SFBuildingTradesCouncil.org Council Enters Into Historic Community Workforce Agreement With UCSF, Creating 1,000 Long-Term Construction Jobs w The 10-year, $3 Billion Project Will Result in a New State-of-the-Art Hospital for the City, Good-Paying Work for Tradespeople, and More an Francisco’s Gonzalez said. “It couldn’t have OF UCSF COURTESY building and con- come at a more crucial moment struction trades in our city’s history.” workers can count To ensure the highest quality, a massive new safety, and efficiency in con- projectS in the “win” column: struction, the Council will enter construction of the new hos- into the agreement on behalf of pital at UCSF Helen Diller its 60,000 local skilled workers Medical Center at Parnas- in 32 trade unions. The pact, the sus Heights. Last month, the first of its kind for the Univer- San Francisco Building and sity of California system, is a Construction Trades Coun- formal agreement between the cil, together with UC San Council and HBW, the general Francisco and Herrero Boldt contractor hired by UCSF. It Webcor (HBW), announced a ensures that the $3 billion build- Community Workforce Agree- ing project will employ a union ment (CWA) that will pro- workforce with strong represen- The UCSF Parnassus Heights Campus is seen here as it currently exists. The new hospital will take better mote collaboration between tation of local labor. advantage of its beautiful surroundings, with a plan in place to better integrate it into the serene green the university, labor unions (continued on page 9) space at the foot of Mount Sutro. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 155, Pt. 3 February

3826 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 155, Pt. 3 February 12, 2009 Committee on Intelligence be author- In 1976, he ran and won election to ner that reflects the true values of this ized to meet during the session of the the U.S. House of Representatives, and country. Senate on February 12, 2009 at 2:30 p.m. he served in the House for 16 years. The committee did its work. It ques- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without During that time, he also served as tioned Mr. Panetta on a broad array of objection, it is so ordered. chairman of the Budget Committee. issues he will confront as Director of f In 1993, he joined the Clinton admin- the CIA, and it submitted followup istration as head of the Office of Man- questions, all of which were answered. EXECUTIVE SESSION agement and Budget. In July 1994, Mr. These questions, and Mr. Panetta’s Panetta became President Clinton’s answers, can be found at the Intel- EXECUTIVE CALENDAR chief of staff. ligence Committee Web site. He served in that capacity until Jan- I urge all Members of the Senate, as Mr. BEGICH. Mr. President, I ask uary 1997, when he returned to Cali- well as the public, to review them in unanimous consent that the Senate fornia to found and lead the Leon and order to obtain a better understanding proceed to executive session to con- Sylvia Panetta Institute for Public of his views about the office to which sider Calendar No. 17, the nomination Policy at California State University he has been nominated.