Yosemite Foundation Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yosemite National Park U.S

National Park Service Yosemite National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The Ahwahnee Comprehensive Rehabilitation Plan Where is The Ahwahnee is located in Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park. The Ahwahnee area the project includes a National Historic Landmark hotel, as well as guest cottages, an employee dormitory, and located? associated grounds and landscaping. Built in 1927, The Ahwahnee hotel is an iconic landmark and is used year-round by both overnight and day visitors to Yosemite Valley. After more than 80 years in service, the hotel and associated structures are in need of rehabilitation because: Why Facilities at The Ahwahnee are not fully compliant with the most recent building and undertake this planning accessibility codes, including: International Building Code (IBC) effort? National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Code Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and IBC seismic requirements; and Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards. Many of the electrical, plumbing and mechanical systems serving The Ahwahnee facilities are aging and need to be replaced and updated. Some historic hotel finishes and landscape components are time-worn or have been altered over the years, potentially affecting the historic integrity of this property. The current operational layout of some working areas reduces the efficiency of providing a high level of visitor services. The purpose of this project is to develop a comprehensive plan for phased, long-term rehabilitation of The Ahwahnee National Historic Landmark hotel and associated guest cottages, employee dormitory, What does and landscaped grounds in order to: this plan propose? Restore, preserve, and protect the historic integrity and character-defining features of The Ahwahnee by rehabilitating aged or altered historic finishes and contributing landscape features. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Yosemite National Park Visitor Study: Winter 2008

Social Science Program National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Yosemite National Park Visitor Study Winter 2008 Park Studies Unit Visitor Services Project Report 198 Social Science Program National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Yosemite National Park Visitor Study Winter 2008 Park Studies Unit Visitor Services Project Report 198 October 2008 Yen Le Eleonora Papadogiannaki Nancy Holmes Steven J. Hollenhorst Dr. Yen Le is VSP Assistant Director, Eleonora Papadogiannaki and Nancy Holmes are Research Assistants with the Visitor Services Project and Dr. Steven Hollenhorst is the Director of the Park Studies Unit, Department of Conservation Social Sciences, University of Idaho. We thank Jennifer Morse, Paul Reyes, Pixie Siebe, and the staff of Yosemite National Park for assisting with the survey, and David Vollmer for his technical assistance. Yosemite National Park – VSP Visitor Study February 2–10, 2008 Visitor Services Project Yosemite National Park Report Summary • This report describes the results of a visitor study at Yosemite National Park during February 2-10, 2008. A total of 938 questionnaires were distributed to visitor groups. Of those, 563 questionnaires were returned, resulting in a 60% response rate. • This report profiles a systematic random sample of Yosemite National Park. Most results are presented in graphs and frequency tables. Summaries of visitor comments are included in the report and complete comments are included in the Visitor Comments Appendix. • Fifty percent of visitor groups were in groups of two and 25% were in groups of three or four. Sixty percent of visitor groups were in family groups. -

{Osemite Nature Notes F Di.Ljme Xxxvii - Number 12 December 1958 Nationai Park R Service

{OSEMITE NATURE NOTES F DI.LJME XXXVII - NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1958 NATIONAI PARK R SERVICE IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . —Anderson NPC Organized cross-country skiing is an excellent way to enjoy the winter beauty of Yosemite's high country . in its 37th year of public service. The YOSEMITE monthly publication of Yosemite 's park naturalists and the Yosemite Natural Nature Notes History Association. John C . Preston, Superintendent D . H . Hubbard, Park Naturalist Robert F . Upton, Assoc . Park Naturalist P . F . McCrary, Asst . Park Naturalist S . J . Zachwieja, Junior Park Naturalist Robert A . Groin, Park Naturalist Trainee VOL . XXXVII DECEMBER 1958 NO . 12 TIOGA PEAK By William Neely, Ranger-Naturalist P When climbing our Tuolumne Glaciers have never been up here. mountains it is difficult to remember During glacial ages the ice gathered that they have not been pushed up in hollows on slopes and ground their individually, but rather that they way down valleys . The mountain are remnants of flat land that has tops, if high enough, were spared been cut away. Here we hike much and stood above the Tuolumne ice of the time in glacier-scoured, glacier- field as isolated peaks or nunataks, worn, glacier-sculptured topography being gnawed away on all sides. and see the new surfaces, the work Cockscomb and Cathedral peaks are of ice chisels and ice tools, the signs of action and tremendous grinding the spiry fragments of once fatter . The ice, working easily forces. But there is that region above mountains that is untouched by glacier work, a in the vertical joint planes and cracks quiet and ancient region . -

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

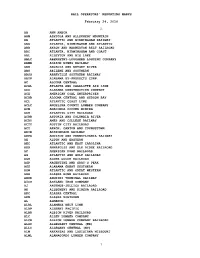

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

Castle Crags State Park Brochure

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is Castle Crags to provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping he lofty spires and to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological T State Park diversity, protecting its most valued natural and granite dome of Castle Crags cultural resources, and creating opportunities for high-quality outdoor recreation. rise to more than 6,500 feet. The grandeur of the crags has been revered as California State Parks supports equal access. an extraordinary place Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the park for millennia. at (530) 235-2684. This publication can be made available in alternate formats. Contact [email protected] or call (916) 654-2249. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Discover the many states of California.™ Castle Crags State Park 20022 Castle Creek Road Castella, CA 96017 (530) 235-2684 © 2014 California State Parks M ajestic Castle Crags have inspired The Okwanuchu Shasta territory covered A malaria epidemic brought by European fur enduring myths and legends since about 700 square miles of forested mountains trappers wiped out much of the Okwanuchu prehistoric times. More than 170 million from the headwaters of the Sacramento River Shasta populace by 1833. years old, these granite formations in to the McCloud River and from Mount Shasta With the 1848 gold discoveries at the the Castle Crags Wilderness border the to Pollard Flat. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park July 29, 2015 - September 1, 2015 1, September - 2015 29, July Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS 1904. Grove, Mariposa Monarch, Fallen the astride Soldiers” “Buffalo Cavalry 9th D, Troop Volume 40, Issue 6 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

BAYLANDS & CREEKS South San Francisco

Oak_Mus_Baylands_SideA_6_7_05.pdf 6/14/2005 11:52:36 AM M12 M10 M27 M10A 121°00'00" M28 R1 For adjoining area see Creek & Watershed Map of Fremont & Vicinity 37°30' 37°30' 1 1- Dumbarton Pt. M11 - R1 M26 N Fremont e A in rr reek L ( o te C L y alien a o C L g a Agua Fria Creek in u d gu e n e A Green Point M a o N l w - a R2 ry 1 C L r e a M8 e g k u ) M7 n SF2 a R3 e F L Lin in D e M6 e in E L Creek A22 Toroges Slou M1 gh C ine Ravenswood L Slough M5 Open Space e ra Preserve lb A Cooley Landing L i A23 Coyote Creek Lagoon n M3 e M2 C M4 e B Palo Alto Lin d Baylands Nature Mu Preserve S East Palo Alto loug A21 h Calaveras Point A19 e B Station A20 Lin C see For adjoining area oy Island ote Sand Point e A Lucy Evans Lin Baylands Nature Creek Interpretive Center Newby Island A9 San Knapp F Map of Milpitas & North San Jose Creek & Watershed ra Hooks Island n Tract c A i l s Palo Alto v A17 q i ui s to Creek Baylands Nature A6 o A14 A15 Preserve h g G u u a o Milpitas l Long Point d a S A10 A18 l u d p Creek l A3N e e i f Creek & Watershed Map of Palo Alto & Vicinity Creek & Watershed Calera y A16 Berryessa a M M n A1 A13 a i h A11 l San Jose / Santa Clara s g la a u o Don Edwards San Francisco Bay rd Water Pollution Control Plant B l h S g Creek d u National Wildlife Refuge o ew lo lo Vi F S Environmental Education Center . -

2018 Spring WTC Newsletter

Vol. 29, No. 1 / Spring 2018 Blood, Sweat and Ink on the PCT (pg. 2) Is This the End? (pg. 5) Adventure in Your Own Backyard (pg. 6) Experience Trips: You Want Them, We’ve Got Them! (pg. 12) Shawnté Salabert, guidebook author and WTC instructor, on the Pacific Crest Trail WTC OFFICERS Contents (see your Student Handbook for contact information) WTC Chair WTC Outings Co-Chairs Bob Myers Adrienne Benedict Tom McDonnell WTC Registrar FEATURES Jim Martins LONG BEACH/SOUTH BAY SAN GABRIEL VALLEY Smiles, Not Miles Area Chair Area Chair Writer and WTC-instructor Shawnté Salabert spent 2 Brian Decker Jeremy Netka more than two years writing the guidebook on Area Vice Chair Area Vice Chair section hiking the southern section of the Pacific Sharon Moore Jan Marie Perry Crest Trail—and she’s got some advice for you. Area Trips Area Trips Mike Adams Mat Kelliher Is This the End? Spoiler alert—no, it isn’t! Lubna Debbini and Victor 5 Area Registrar Area Registrar Joan Rosenburg Amy Smith Gomez point you down the road of post-WTC fun and adventure. ORANGE COUNTY WEST LOS ANGELES Area Chair Area Chair Adventure in Your Own Backyard Matt Hengst Pamela Sivula Ditch the long drive—in Southern California 6 Area Vice Chair Area Vice Chair there’s adventure right out the back door and Gary McCoppin Katerina Leong Will McWhinney has a few ideas. Area Trips Area Trips Matt Hengst Adrienne Benedict Alphabet Soup Dig into the Angeles Chapter’s sections and you 8 Area Registrar Area Registrar find plenty of outdoor and other possibilities— Wendy Miller Pamela Sivula and acronyms. -

Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S

Yosemite National Park National Park Service Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S. Department of the Interior To To ) S k Tioga n Tioga m e To o e k w r Road 10 Shuttle Route / Stop Road 7 Tioga . C Ranger Station C 4 n 3.I mi (year round) 6.9 mi ( Road r e i o 5.0 km y I e II.I km . 3.6 mi m n 6 k To a 9 m 5.9 km 18 Shuttle Route / Stop . C Self-guiding Nature Trail Tioga North 0 2 i Y n ( . o (summer only) 6 a Road 2 i s . d 6 m e 5.0 mi n m k i I Trailhead Parking ( 8.0 km m Bicycle / Foot Path I. it I.3 0 e ) k C m (paved) m re i ( e 2 ) ) k . Snow I Walk-in Campground m k k m Creek Hiking Trail .2 k ) Falls 3 Upper e ( e Campground i r Waterfall C Yosemite m ) 0 Fall Yosemite h I Kilometer . c r m 2 Point A k Store l 8 6936 ft . a ) y 0 2II4 m ( m I Mile o k i R 9 I. m ( 3. i 2 5 m . To Tamarack Flat North m i Yosemite Village 0 Lower (5 .2 Campground . I I Dome 2.5 mi Yosemite k Visitor Center m 7525 ft 0 Fall 3.9 km ) 2294 m . 3 k m e Cre i 2.0 mi Lower Yosemite Fall Trail a (3 To Tamarack Flat ( Medical Royal Mirror .2 0 y The Ahwahnee a m) k .