C:\Faili\DARBI\Daugavpils UNIVERSITATE\Konferences Un

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of Fall 8-21-2012 Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 08/21/2012 This essay is a work in progress. It was uploaded for the first time in August 2012, and the present document is the first version. The author welcomes comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army bands and their bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the bands and bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. Army in World War I. They underwent rapid mobilization and demobilization over 1917-1919, and were for the most part unconnected by personnel or traditions to the long-established bands of the four black regular U.S. Army regiments that preceded them and continued to serve after them. Pressed to find sufficient numbers of willing and able black band leaders, the army turned to schools and the entertainment industry for the necessary talent. -

Fabulously Tidal — Issue 117, 1 January 2018

Fabulously Tidal — Issue 117, 1 January 2018 SPONSORED FEATURE — PHILIP SAWYERS' THIRD SYMPHONY Alice McVeigh: 'This is a fabulously tidal symphony, with wild expanses of differing moods, but it begins with a ripple of unease. We in the cello section were told to play the opening with as much stillness as possible, allowing the first theme to grow as it weaves into violins and violas, into threads of flute and oboe, and — from there — into a tempestuous section of interweaving themes. The argument descends into a woodwind quarrel, resolved by flute and oboe, decorated by horns — while the strings continue to niggle and churn away at any sense of calm. 'Then solo bassoon ignites a new, still tenser, section. The violins take over, lightly but resolutely, answered by middle strings conveying a sense of tenderness — but with a bitter aftertaste. (This is incidentally one of Sawyers' most characteristic strengths: a tenderness, never saccharine, often undermined by subtle discontent.) From the brass comes the first glimpse of escape: the powerful broken octave theme over which the other themes furiously contend. 'The cellos at the recapitulation, now deepened and enriched, are twisted by Sawyers into something passionate and grounded in lower brass, reinforced by timpani. The movement ends with the heavy brass seemingly triumphant over the strings' stubborn reiteration of the theme. Still, the lower strings' pessimism prevails. 'Tutti violins kick-start the second movement with a dramatic leap from their richest register, only yielding to keening solo oboe. 'The sobered strings leave the solo winds to mourn, yet, with characteristic Sawyers intensity, something is brewing at subterranean depths: eventually, the violas' chuntering is answered by full insistent brass, in a stormily ecstatic tantrum. -

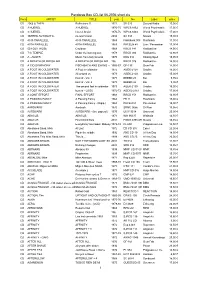

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell Glenn Miller Original release label “Sun Valley Serenade” Though Glenn Miller and His Orchestra’s well-known, robust and swinging hit “In the Mood” was recorded in 1939 (and was written even earlier), it has since come to symbolize the 1940s, World War II, and the entire Big Band Era. Its resounding success—becoming a hit twice, once in 1940 and again in 1943—and its frequent reprisal by other artists has solidified it as a time- traversing classic. Covered innumerable times, “In the Mood” has endured in two versions, its original instrumental (the specific recording added to the Registry in 2004) and a version with lyrics. The music was written (or written down) by Joe Garland, a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith who also composed “Leap Frog” for Les Brown and his band. The lyrics are by Andy Razaf who would also contribute the words to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose.” For as much as it was an original work, “In the Mood” is also an amalgamation, a “mash-up” before the term was coined. It arrived at its creation via the mixture and integration of three or four different riffs from various earlier works. Its earliest elements can be found in “Clarinet Getaway,” from 1925, recorded by Jimmy O’Bryant, an Arkansas bandleader. For his Paramount label instrumental, O’Bryant was part of a four-person ensemble, featuring a clarinet (played by O’Bryant), a piano, coronet and washboard. Five years later, the jazz piece “Tar Paper Stomp” by Joseph “Wingy” Manone, from 1930, beget “In the Mood’s” signature musical phrase. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

Piotr Illitch Tchaikovsky

Esoteric Profile of Piotr Ilitch Tchaikovsky May 7, 1840 – November 6, 1893 By Marilene dos Santos 1 - Mini Biography Introduction Piotr Ilitch Tchaikovsky was a Russian composer of the Romantic era, born on May 7, 1840, 6:35 AM in Votkinsk, Vyatka region, Russia. His works include symphonies, concertos, operas, ballets, chamber music, and a choral setting of the Russian Orthodox Divine Liturgy. Some of these are among the most popular theatrical music in the classical repertoire including the ballets Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally, which he bolstered with appearances as a guest conductor later in his career in Europe and the United States. Tchaikovsky was honored in 1884 by Emperor Alexander III, and awarded a lifetime pension in the late 1880s. Family Tchaikovsky was born to a fairly wealthy middle class family. His father, named Ilya Tchaikovsky was a mining business executive in Votkinsk. His father's ancestors were from Ukraine and Poland. His mother, named Aleksandra Assier, was of Russian and French ancestry. His father, Ilya Petrovich (a two time divorced) married Alexandra and the two had two sons, Pyotr and Modest. Childhood and Mother death Tchaikovsky started piano studies at five and soon showed remarkable gifts. He also learned to read French and German by the age of six. A year later, he was writing French verses. The family hired a governess, Fanny Dürbach, to keep watch over the children, and she often referred to Tchaikovsky as the "porcelain child." Tchaikovsky was ultra sensitive to music. -

Thejoy That Comes with Music

(I Jnfernafionaf JlJRJ8Jl SEND IN YOUR SUGGESTIONS FOR RECUTTING BY NICK JARRETT Mieczyslaw Manz, 75, Is Dead; I know many of us have a pet roll or rolls we would A Concert Pianist and Teacher like to see recut. I took this matter up with . Mieczyslaw Munz, a fonner major, the Brahms concerto in Elwood Hansen, owner of the plant at Turlock. He concert pianist who appeared D minor and the Franck Sym assured me that there is no exclusive contract to ~ith many of the.world's lead- phonic Variations. prevent such a project, and suggested that I might 109 orchestras, di~ yesterday Mr Munz made his solo of a heart attack 10 an ambu-' . co-ordinate requests from the membership. Please lance as he was being taken to debut at Aeoli:an, Hall 10 New write and let me know what ~ would like. hospital from his home at the York on Oct. 20, 1922. The Ten Park Avenue Hotel. He New York Times review called was 75 years old. him "an absorbed artist, under It has been suggested that special attention be Mr. Munz, who taught at the whose hands mere tricks and given to the type of rolls that seldom appear on Juilliard School for 12 years, graces of piano playm'.. fall was scheduled to return to the . • lists of recuts: PIANO music played by the great Juilliard School next month, away as chips from the sculp- artists of the reproducing piano's heyday. This is after a sabbatical year of teach- tor's chisel, wbliIe he lays ~are iing at Giebel University in the larger curves of sustamed not an attempt to put AMR or Klavier out of business, Tokyo. -

Review of “22 Chopin Studies” by Leopold Godowsky by OPUS KLASSIEK , Published on 25 February 2013

Review of “22 Chopin Studies” by Leopold Godowsky by OPUS KLASSIEK , published on 25 February 2013 Leopold Godowsky (Zasliai, Litouwen 1870 - New York 1938) was sailing with the tide around 1900: the artistic and culturally rich turn of the century was a golden age for pianists. They were given plenty of opportunities to expose their pianistic and composing virtuosity (if they didn't demand the opportunities outright), both on concert stages as well as in the many music salons of the wealthy. Think about such giants as Anton Rubinstein, Jan Paderewski, Josef Hoffmann, Theodor Leschetizky, Vladimir Horowitz, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Ferruccio Busoni and Ignaz Friedman. The era of that other great piano virtuoso, Franz Liszt, was actually not even properly past. Liszt, after all, only returned from his last, very successful, but long and exhausting concert tour in the summer of 1886. The tour, through England and France, most likely did him in. (He died shortly afterwards, on the 31st of July 1886, at the age of seventy-four). Leopold Godowsky Godowsky's contemporaries called him the 'Buddha' of the piano, and he left a legacy of more than four hundred compositions, which make it crystal-clear that he knew the piano inside and out. Even more impressive, he shows in his compositions that as far as the technique of playing he had more mastery than his great contemporary Rachmaninoff, which clearly means something! It was by the way the very same Rachmaninoff who saw in Godowsky the only musician that made a lasting contribution to the development of the piano. -

Documenta Polonica Ex Archivo Generali Hispaniae in Simancas

DOCUMENTA POLONICA EX ARCHIVO GENERALI HISPANIAE IN SIMANCAS Nova series Volumen I POLISH ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DOCUMENTA POLONICA EX ARCHIVO GENERALI HISPANIAE IN SIMANCAS Nova series Volumen I Edited by Ryszard Skowron in collaboration with Miguel Conde Pazos, Paweł Duda, Enrique Corredera Nilsson, Matylda Urjasz-Raczko Cracow 2015 Research financed by the Minister for Science and Higher Education through the National Programme for the Development of Humanities in 2012-2015 Editor Ryszard Skowron English Translation Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz Proofreading of Spanish Texts Cristóbal Sánchez Martos Proofreading of Latin Texts Krzysztof Pawłowski Design & DTP Renata Tomków © Copyright by Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences (PAU) & Ryszard Skowron ISBN 978-83-7676-233-3 Printed and Bound by PASAŻ, ul. Rydlówka 24, Kraków Introduction Between 1963 and 1970, as part of its series Elementa ad Fontiun Editiones, the Polish Historical Institute in Rome issued Documenta polonica ex Archivo Generali Hispaniae in Simancas, seven volumes of documents pertinent to the history of Poland edited by Rev. Walerian Meysztowicz.1 The collections in Simancas are not only important for understanding Polish-Spanish relations, but also very effectively illustrate Poland’s foreign policy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and the role the country played in the international arena. In this respect, the Spanish holdings are second only to the Vatican archives. In terms of the quality and quantity of information, not even the holdings of the Vienna archives illuminate Poland’s European politics on such a scale. Meysztowicz was well aware of this, opening his introduction (Introductio) to the first part of the publication with the sentence: “Res gestae Christianitatis sine Archivo Septimacensi cognosci vix possunt.”2 1 Elementa ad Fontium Editiones, vol. -

Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 8

225187 bk Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 8 Claudius zugeschriebenen Gedichts. Litanei, Robert Braun gewidmet, nach der DDD In Wohin?, dessen Widmungsträger Sergej Vertonung eines Gedichts von Johann Georg Jacobi, ist Rachmaninow ist, bearbeitet Godowsky das zweite Lied ein Gebet für den Seelenfrieden der Verstorbenen. Das Leopold 8.225187 der Schönen Müllerin, in dem der junge Müllersbursche Originallied und die Transkription sind von einer den Bach hört, dessen sanftes Rauschen, in der Stimmung inneren Friedens durchzogen. Klavierfassung eingefangen, ihn aufzufordern scheint, Godowskys Schubert-Transkriptionen enden mit GODOWSKY seine Reise fortzusetzen, doch wohin? einem Konzertarrangement der Ballettmusik zu Die junge Nonne, David Saperton gewidmet, Rosamunde aus dem Jahr 1923 und der Bearbeitung des basiert auf der Vertonung eines Gedichts von Jacob dritten Moment musical op. 94 von 1922. Schubert Transcriptions Nicolaus Craigher. Die junge Nonne kontrastiert den in der Natur brausenden Sturm mit dem Frieden und Keith Anderson Wohin? • Wiegenlied • Die Forelle • Das Wandern • Passacaglia ewigen Lohn des religiösen Lebens. Deutsche Fassung: Bernd Delfs Konstantin Scherbakov, Piano 8.225187 8 225187 bk Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 2 Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938) für 44 Variationen in der traditionellen barocken Form, Godowsky jede Strophe des Original-Lieds. Piano Music Volume 6: Schubert Transcriptions zu denen u.a. auch eine gelungene Anspielung auf den Das Wandern ist das erste Lied des Zyklus Die Erlkönig zählt. Die Variationen, in denen das Thema in schöne Müllerin, in dem der junge Müllersbursche seine The great Polish-American pianist Leopold Godowsky of Saint-Saëns, Godowsky transcribed for piano his unterschiedlichen Gestalten und Registern zurückkehrt, Wanderung beginnt. -

NORDIC COOL 2013 Feb. 19–Mar. 17

NORDIC COOL 2013 DENMARK FINLAND Feb. 19–MAR. 17 ICELAND NorwAY SWEDEN THE KENNEDY CENTER GREENLAND THE FAroE ISLANDS WASHINGTON, D.C. THE ÅLAND ISLANDS Nordic Cool 2013 is presented in cooperation with the Nordic Council of Ministers and Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Presenting Underwriter HRH Foundation Festival Co-Chairs The Honorable Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, Marilyn Carlson Nelson, and Barbro Osher Major support is provided by the Honorable Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, Mrs. Marilyn Carlson Nelson and Dr. Glen Nelson, the Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation, David M. Rubenstein, and the State Plaza Hotel. International Programming at the Kennedy Center is made possible through the generosity of the Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts. NORDIC COOL 2013 Perhaps more so than any other international the Faroe Islands… whether attending a performance festival we’ve created, Nordic Cool 2013 manifests at Sweden’s Royal Dramatic Theatre (where Ingmar the intersection of life and nature, art and culture. Bergman once presided), marveling at the exhibitions in Appreciation of and respect for the natural environment the Nobel Prize Museum, or touring the National Design are reflected throughout the Nordic countries—and Museum in Helsinki (and being excited and surprised at they’re deeply rooted in the arts there, too. seeing objects from my personal collection on exhibit there)… I began to form ideas and a picture of the The impact of the region’s long, dark, and cold winters remarkable cultural wealth these countries all possess. (sometimes brightened by the amazing light of the , photo by Sören Vilks Sören , photo by aurora borealis).