Out of the Best Books: Mormon Assimilation and Exceptionalism Through Secular Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relief Society

9. Relief Society The Relief Society is an auxiliary to the priesthood. in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith All auxiliary organizations exist to help Church [1998], 185). members grow in their testimonies of Heavenly The Relief Society was “divinely made, divinely Father, Jesus Christ, and the restored gospel. authorized, divinely instituted, divinely ordained of Through the work of the auxiliaries, members God” ( Joseph F. Smith, in Teachings: Joseph F. Smith, receive instruction, encouragement, and support as 184). It operates under the direction of priest- they strive to live according to gospel principles. hood leaders. 9.1 9.1.3 Overview of Relief Society Motto and Seal The Relief Society’s motto 9.1.1 is “Charity never faileth” Purposes (1 Corinthians 13:8). This prin- ciple is reflected in its seal: Relief Society helps prepare women for the bless- ings of eternal life as they increase faith in Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ and His Atonement; 9.1.4 strengthen individuals, families, and homes through Membership ordinances and covenants; and work in unity to help All adult women in the Church are members of those in need. Relief Society accomplishes these Relief Society. purposes through Sunday meetings, other Relief Society meetings, service as ministering sisters, and A young woman normally advances into Relief welfare and compassionate service. Society on her 18th birthday or in the coming year. By age 19, each young woman should be fully participating in Relief Society. Because of individ- 9.1.2 ual circumstances, such as personal testimony and History maturity, school graduation, desire to continue with The Prophet Joseph Smith organized the Relief peers, and college attendance, a young woman may Society on March 17, 1842. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Doctrine and Covenants Stories

CHAPTER 52 The Relief Society March 1842 he Saints were building the temple in Nauvoo. TThe men’s clothes were wearing out, and the women wanted to help them. One woman said she would make clothes for the men, but she didn’t have money to buy cloth. Sarah Kimball said she would give the woman some The women asked Eliza R. Snow to write some rules for cloth. Sister Kimball also asked other women to help. the society. She took the rules to Joseph Smith. He said The women had a meeting in Sister Kimball’s home and the rules were good, but he also said the Lord had a decided to start a society for women in the Church. better plan for the women. 186 Joseph Smith asked the women to come to a meeting. their society. Emma Smith was chosen to be the leader of He said priesthood leaders would help the women with the women. They called their group the Relief Society. 187 Joseph Smith told the women to help people who were The women had meetings to learn the things they sick or poor. They should give people any help they needed to know. They were very glad they could help needed. The bishop would help the women know what the members of the Church. to do. The women made clothes for the men who were building The women took food to people who needed it. They the temple. They also made items to be used in the temple. took care of people who were sick and did many other things to help the Saints. -

In Union Is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1998 In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900 Kathleen C. Haggard Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Haggard, Kathleen C., "In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900" (1998). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 738. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/738 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. " IN UNION IS STRENGTH" MORMON WOMEN AND COOPERATION, 1867-1900 by Kathleen C. Haggard A Plan B thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1998 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Anne Butler, for never giving up on me. She not only encouraged me, but helped me believe that this paper could and would be written. Thanks to all the many librarians and archival assistants who helped me with my research, and to Melissa and Tige, who would not let me quit. I am particularly grateful to my parents, Wayne and Adele Creager, and other family members for their moral and financial support which made it possible for me to complete this program. Finally, I express my love and gratitude to my husband John, and our children, Lindsay and Mark, for standing by me when it meant that I was not around nearly as much as they would have liked, and recognizing that, in the end, the late nights and excessive typing would really be worth it. -

Sunday Lesson: Family History Stories

Sunday Lesson: Family History Stories This outline is for a Sunday lesson to be taught by the bishop in a combined group of Melchizedek Priesthood holders, Relief Society sisters, and youth and singles 12 years and older. In preparing for the lesson, it will be helpful to click on the following links and watch the videos suggested for this lesson. Download those you will use. Now I’m Converted He Was a Blacksmith It’s Easier Than Ever Watching My Grandson Play Ball It will also be helpful to: Read the New York Times article, The Stories That Bind Us. Review the booklet, My Family: Stories That Bring Us Together. Prayerfully decide which discussion questions you would like to use. 1. INTRODUCTION Begin with prayer. Explain that the family history experience has changed. The objective of today’s class is to introduce members to a new approach that includes: . Working together as families in their homes on their family history. Using the Church’s website FamilySearch.org that has been redesigned to be easier to use anywhere on any device. Using the booklet My Family: Stories That Bring Us Together, which is an easier way for families and youth to get started doing family history. Receiving help from the ward family history consultant and high priests group leader. Introduce these leaders to the class. 2. USING FAMILY HISTORY TO INVOLVE YOUTH Watch: Now I’m Converted Discussion Questions: 1 . Q: What insights does this video provide concerning our youth’s ability to organize and carry out family history efforts? A: Youth are very capable of organizing and conducting family history efforts activities. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986

Journal of Mormon History Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 1 1986 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Table of Contents • --Mormon Women, Other Women: Paradoxes and Challenges Anne Firor Scott, 3 • --Strangers in a Strange Land: Heber J. Grant and the Opening of the Japanese Mission Ronald W. Walker, 21 • --Lamanism, Lymanism, and Cornfields Richard E. Bennett, 45 • --Mormon Missionary Wives in Nineteenth Century Polynesia Carol Cornwall Madsen, 61 • --The Federal Bench and Priesthood Authority: The Rise and Fall of John Fitch Kinney's Early Relationship with the Mormons Michael W. Homer, 89 • --The 1903 Dedication of Russia for Missionary Work Kahlile Mehr, 111 • --Between Two Cultures: The Mormon Settlement of Star Valley, Wyoming Dean L.May, 125 Keywords 1986-1987 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff LEONARD J. ARRINGTON, Editor LOWELL M. DURHAM, Jr., Assistant Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Assistant Editor FRANK McENTIRE, Assistant Editor MARTHA ELIZABETH BRADLEY, Assistant Editor JILL MULVAY DERR, Assistant Editor Board of Editors MARIO DE PILLIS (1988), University of Massachusetts PAUL M. -

Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-19-2011 Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R. Ricketts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ricketts, eJ remy R.. "Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeremy R. Ricketts Candidate American Studies Departmelll This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Commillee: , Chairperson Alex Lubin, PhD &/I ;Se, tJ_ ,1-t C- 02-s,) Lori Beaman, PhD ii IMAGINING THE SAINTS: REPRESENTATIONS OF MORMONISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE BY JEREMY R. RICKETTS B. A., English and History, University of Memphis, 1997 M.A., University of Alabama, 2000 M.Ed., College Student Affairs, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2011 iii ©2011, Jeremy R. Ricketts iv DEDICATION To my family, in the broadest sense of the word v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been many years in the making, and would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. My dissertation committee has provided invaluable guidance during my time at the University of New Mexico (UNM). -

More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women As Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2017 More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860 Kim M. (Kim Michaelle) Davidson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Davidson, Kim M. (Kim Michaelle), "More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860" (2017). WWU Graduate School Collection. 558. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/558 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans 1830-1860 By Kim Michaelle Davidson Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Jared Hardesty Dr. Hunter Price Dr. Holly Folk MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

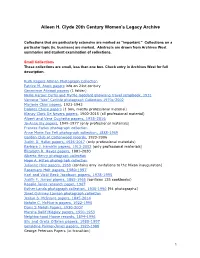

Clyde Archive Finding

Aileen H. Clyde 20th Century Women's Legacy Archive Collections that are particularly extensive are marked as “important.” Collections on a particular topic (ie. business) are marked. Abstracts are drawn from Archives West summaries and student examination of collections. Small Collections These collections are small, less than one box. Check entry in Archives West for full description. Ruth Rogers Altman Photograph Collection Patrice M. Arent papers info on 21st century Genevieve Atwood papers (1 folder) Nellie Harper Curtis and Myrtle Goddard Browning travel scrapbook, 1931 Vervene “Vee” Carlisle photograph Collection 1970s-2002 Marjorie Chan papers, 1921-1943 Dolores Chase papers (1 box, mostly professional material) Klancy Clark De Nevers papers, 1900-2015 (all professional material) Albert and Vera Cuglietta papers, 1935-2016 Jo-Anne Ely papers, 1949-1977 (only professional materials) Frances Farley photograph collection Anne Marie Fox Felt photograph collection, 1888-1969 Garden Club of Cottonwood records, 1923-2006 Judith D. Hallet papers, 1926-2017 (only professional materials) Barbara J. Hamblin papers, 1913-2003 (only professional materials) Elizabeth R. Hayes papers, 1881-2020 Alberta Henry photograph collection Hope A. Hilton photograph collection Julianne Hinz papers, 1969 (contains only invitations to the Nixon inauguration) Rosemary Holt papers, 1980-1997 Karl and Vicki Beck Jacobson papers, 1978-1995 Judith F. Jarrow papers, 1865-1965 (contains 135 cookbooks) Rosalie Jones research paper, 1967 Esther Landa photograph collection, 1930-1990 [94 photographs] Janet Quinney Lawson photograph collection Jerilyn S. McIntyre papers, 1845-2014 Natalie C. McMurrin papers, 1922-1995 Doris S Melich Papers, 1930-2007 Marsha Ballif Midgley papers, 1950-1953 Neighborhood House records, 1894-1996 Stu and Greta O’Brien papers, 1980-1997 Geraldine Palmer-Jones papers, 1922-1988 George Peterson Papers (in transition) 1 Ann Pingree Collection, 2011 Charlotte A. -

Church News - New Mission Presidents Church News

7/7/2014 Church News - New mission presidents Church News New mission presidents Published: Saturday, Jan. 24, 1998 Eight new mission presidents have been called by the First Presidency. The mission presidents and their wives will begin their service about July 1. Their assignments will be announced later. The new mission presidents are: - Richard M. Andrus, 61, San Luis Obispo 1st Ward, San Luis Obispo California Stake; former stake president and counselor, bishop and counselor, and missionary in the Western Canadian Mission; retired personnel director for San Luis Coastal Unified School District; received bachelor's degree in education from California State University-Los Angeles, and master's degree in educational administration from California State Polytechnic University-San Luis Obispo; born in Bell, Calif., to Richard Morris and Roma Irene Boston Andrus; married Darlene Hill, five children. She is a Relief Society instructor; former stake missionary, Young Women president and teacher, counselor in Relief Society presidency, teacher development instructor, and missionary in the Spanish American Mission; received real estate license from Lumbleau Real Estate School and attended Cuesta College and BYU; born in Salt Lake City to John Hyrum Hill Jr. and Clara Vada Horne Hill.- Steven R. Ballard, 51, Harmony Park Ward, Mesa Arizona Kimball Stake; high councilor; former high councilor, bishop, elders quorum president and instructor, assistant deacons quorum adviser, and Sunday School teacher; owner of Intermedics Southwest; received bachelor's degree in biology from BYU; born in Logan, Utah, to William Wallace and Hannah Jueschke Ballard; married Marta Jo Skousen, six children. She is Relief Society president; former stake Primary president, stake missionary, counselor in Relief Society presidency, organist, and Cub Scout leader; received bachelor's degree in nursing from BYU; born in Mesa, Ariz., to Willard Ivan and Marta Ruth Nielson Skousen. -

First Presidency Letter Dated October 6, 2018

THE GHURGH OF JESUS GHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS OFFICE OF THE FIRST PRESIDENCY 47 EAST SOUTH TEMPLE STREET, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84150·1200 October 6, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, and District Presidents; Bishops and Branch Presidents; Stake and Ward Councils (To be read in sacrament meeting) DearBrothers and Sisters: A New Balancebetween Gospel Instruction in the Home andin the Church For many years, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been working on a home-centered and Church-supported plan for members to learndoctrine, fortify faith, and foster heartfelt worship. Today we announce a significant step in achieving a new balance between gospel instruction in the home andin the Church. Beginning in January 2019, the Sunday schedule followed throughout the Church will include a 60-minute sacrament meeting each Sunday, and aftera 10-minute transition, a SO-minute class period. Sunday School classes will be held in this class period on the firstand third Sundays, and priesthood quorums, Relief Society, and Young Women will be held on the second andfourth Sundays. Primary will be held weekly and will last 50 minutes. In addition, we encourage individuals and families to hold home evening andto study the gospel at home on Sunday--or at other times as individuals and families choose. A new resource, Come, Follow Me-For Individuals and Families, provides ideas for personal scripture study, familyscripture study, and home evening. These adjustments will be implemented in January 2019. Additional information is enclosed and is also available at Sabbath.lds.org. -

Worldwide Leadership Training Meeting the Priesthood and the Auxiliaries of the Relief Society, Young Women, and Primary

Worldwide Leadership Training Meeting The Priesthood and the Auxiliaries of the Relief Society, Young Women, and Primary JANUARY 10, 2004 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 8/03. 24240 Contents Challenges Facing the Family . 1 President James E. Faust The Doctrinal Foundation of the Auxiliaries . 5 Elder Richard G. Scott The Purposes of the Auxiliaries . 9 Bonnie D. Parkin Susan W. Tanner Coleen K. Menlove The Priesthood and the Auxiliaries . 16 Elder Dallin H. Oaks Standing Strong and Immovable . 20 President Gordon B. Hinckley PRESIDENT JAMES E. FAUST to this decline are young people Second Counselor in the First Presidency delaying marriage, increases in the proportion of adult population who have never married, and an increase in cohabitation.3 The marriage rates Challenges Facing in four reported South American countries have dramatically declined in the past decade, and in most the Family European countries they have also dramatically decreased for several decades.4 Studies, however, show that Latter-day Saints are more likely to marry than people in the general population and also that men who marry generally live longer and are more healthy and happy than those who do not.5 righteous living are the church and At the heart of a happy family is the family. complete devotion of both parents The family relationship of father, to each other. In terms of sexual mother, and children is the oldest intimacy, the Lord’s law is abstinence and most enduring institution in the before marriage and fidelity after- world.