Factsheet: Impacts of Recreational Fishing on Wildlife and Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kansas Fishing Regulations Summary

2 Kansas Fishing 0 Regulations 0 5 Summary The new Community Fisheries Assistance Program (CFAP) promises to increase opportunities for anglers to fish close to home. For detailed information, see Page 16. PURCHASE FISHING LICENSES AND VIEW WEEKLY FISHING REPORTS ONLINE AT THE DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND PARKS' WEBSITE, WWW.KDWP.STATE.KS.US TABLE OF CONTENTS Wildlife and Parks Offices, e-mail . Zebra Mussel, White Perch Alerts . State Record Fish . Lawful Fishing . Reservoirs, Lakes, and River Access . Are Fish Safe To Eat? . Definitions . Fish Identification . Urban Fishing, Trout, Fishing Clinics . License Information and Fees . Special Event Permits, Boats . FISH Access . Length and Creel Limits . Community Fisheries Assistance . Becoming An Outdoors-Woman (BOW) . Common Concerns, Missouri River Rules . Master Angler Award . State Park Fees . WILDLIFE & PARKS OFFICES KANSAS WILDLIFE & Maps and area brochures are available through offices listed on this page and from the PARKS COMMISSION department website, www.kdwp.state.ks.us. As a cabinet-level agency, the Kansas Office of the Secretary AREA & STATE PARK OFFICES Department of Wildlife and Parks is adminis- 1020 S Kansas Ave., Rm 200 tered by a secretary of Wildlife and Parks Topeka, KS 66612-1327.....(785) 296-2281 Cedar Bluff SP....................(785) 726-3212 and is advised by a seven-member Wildlife Cheney SP .........................(316) 542-3664 and Parks Commission. All positions are Pratt Operations Office Cheyenne Bottoms WA ......(620) 793-7730 appointed by the governor with the commis- 512 SE 25th Ave. Clinton SP ..........................(785) 842-8562 sioners serving staggered four-year terms. Pratt, KS 67124-8174 ........(620) 672-5911 Council Grove WA..............(620) 767-5900 Serving as a regulatory body for the depart- Crawford SP .......................(620) 362-3671 ment, the commission is a non-partisan Region 1 Office Cross Timbers SP ..............(620) 637-2213 board, made up of no more than four mem- 1426 Hwy 183 Alt., P.O. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7.841,126 B2 Huppert (45) Date of Patent: Nov.30, 2010

USOO7841 126B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7.841,126 B2 Huppert (45) Date of Patent: Nov.30, 2010 (54) MODULAR SINKER 2004/0000385 A1 1/2004 Ratte ......................... 164f76.1 2009.0114162 A1* 5/2009 Locklear ..................... 119.256 (76) Inventor: Mikel Huppert, 1327 Debra St., Ellsworth, WI (US) 54011 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS JP 11196738 A * 7, 1999 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this JP 200O262197 A * 9, 2000 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 JP 2003125,685 A * 5, 2003 U.S.C. 154(b) by 39 days. JP 2004305108 A * 11, 2004 (21) Appl. No.: 12/082,061 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Machine translation of JP11 196738 A from http://www19.ipdl.inpit. (22) Filed: Apr. 8, 2008 go.jp/PA1/cgi-bin/PA1 INIT?1181685164439.* Machine translation of JP2000262197 A from http://www19.ipdl. (65) Prior Publication Data inpit.go.jp/PA1/cgi-bin/PA1 INIT?1 181685164439.* Machine translation of JP2003125685 A from http://www19.ipdl. US 2009/O249679 A1 Oct. 8, 2009 inpit.go.jp/PA1/cgi-bin/PA1 INIT?1 181685164439.* (51) Int. Cl. * cited by examiner AIK 95/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ..................................................... 43/43.14 Primary Examiner Son TNguyen (58) Field of Classification Search ................ 43/44.87, Assistant Examiner Shadi Baniani 43/42.06, 42.09, 42.31, 43.1, 44.96, 43.14; A0IK 95/00, (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm DLTschida AOIK 95/02 See application file for complete search history. (57) ABSTRACT (56) References Cited An improved slip sinker having a hollow non-buoyant tubular body mounted intermediate a flanged headpiece having a fish U.S. -

FR-29-Kavieng.Pdf

Secretariat of the Pacific Community FIELD REPORT No. 29 on TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE ON SMALL-SCALE BAITFISHING TRIALS AND COURSE PRESENTATION TO THE NATIONAL FISHERIES COLLEGE, AND FAD EXPERIMENTS TO THE COMMUNITY FISHERIES MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT ASSISTING IN KAVIENG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA 12 September to 7 December 2005 by William Sokimi Fisheries Development Officer Secretariat of the Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia 2006 © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2006 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. The SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided the SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. This field report forms part of a series compiled by the Fisheries Development Section of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community’s Coastal Fisheries Programme. These reports have been produced as a record of individual project activities and country assignments, from materials held within the Section, with the aim of making this valuable information readily accessible. Each report in this series has been compiled within the Fisheries Development Section to a technical standard acceptable for release into the public arena. Secretariat -

FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles The Republic of Uzbekistan Part I Overview and main indicators 1. Country brief 2. FAO Fisheries statistics Part II Narrative (2008) 3. Production sector Inland sub-sector Aquaculture sub-sector Recreational sub-sector 4. Post-harvest sector Fish utilization Source of information United Nations Geospatial Information Section http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm Fish markets Imagery for continents and oceans reproduced from GEBCO, www.gebco.net 5. Socio-economic contribution of the fishery sector Role of fisheries in the national economy Supply and demand Trade Food security Employment Rural development 6. Trends, issues and development Constraints and opportunities Government and non-government sector policies and development strategies Research, education and training Foreign aid 7. Institutional framework 8. Legal framework Additional information 9. FAO Thematic data bases 10. Publications 11. Meetings & News archive FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Part I Overview and main indicators Part I of the Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profile is compiled using the most up-to-date information available from the FAO Country briefs and Statistics programmes at the time of publication. The Country Brief and the FAO Fisheries Statistics provided in Part I may, however, have been prepared at different times, which would explain any inconsistencies. Country brief Prepared: March 2018 Uzbekistan covers an area of 447400km2. It is a landlocked country and mountains dominate the landscape in the east and northeast. The fisheries in Uzbekistan comprise two main components, namely inland capture fisheries and aquaculture. -

Tuna Fishing and a Review of Payaos in the Philippines

Session 1 - Regional syntheses Tuna fishing and a review of payaos in the Philippines Jonathan O. Dickson*1', Augusto C. Nativiclacl(2) (1) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, 860 Arcadia Bldg., Quezon Avenue, Quezon City 3008, Philippines - [email protected] (2) Frabelle Fishing Company, 1051 North Bay Blvd., Navotas, Metro Manila, Philippines Abstract Payao is a traditional concept, which has been successfully commercialized to increase the landings of several species valuable to the country's export and local industries. It has become one of the most important developments in pelagic fishing that significantly contributed to increased tuna production and expansion of purse seine and other fishing gears. The introduction of the payao in tuna fishing in 1975 triggered the rapid development of the tuna and small pelagic fishery. With limited management schemes and strategies, however, unstable tuna and tuna-like species production was experienced in the 1980s and 1990s. In this paper, the evolution and development of the payao with emphasis on the technological aspect are reviewed. The present practices and techniques of payao in various parts of the country, including its structure, ownership, distribution, and fishing operations are discussed. Monitoring results of purse seine/ringnet operations including handline using payao in Celebes Sea and Western Luzon are presented to compare fishing styles and techniques, payao designs and species caught. The fishing gears in various regions of the country for harvesting payao are enumerated and discussed. The inshore and offshore payaos in terms of sea depth, location, designs, fishing methods and catch composi- tion are also compared. Fishing companies and fisherfolk associations involved in payao operation are presented to determine extent of uti- lization and involvement in the municipal and commercial sectors of the fishing industry. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 39/Wednesday, February 27, 2019

6576 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 39 / Wednesday, February 27, 2019 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Protected Resources, National Marine active acoustic survey sources. TPWD Fisheries Service, 1315 East-West has requested take of dolphins from four National Oceanic and Atmospheric Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910. stocks, by mortality or serious injury, Administration Instructions: Comments sent by any incidental to gillnet fishing in Texas other method, to any other address or bays. For both applicants, the 50 CFR Part 219 individual, or received after the end of regulations would be valid from 2018 to [Docket No. 161109999–8999–01] the comment period, may not be 2023. considered by NMFS. All comments Legal Authority for the Proposed Action RIN 0648–BG44 received are a part of the public record and will generally be posted for public Section 101(a)(5)(A) of the MMPA (16 Taking and Importing Marine viewing on www.regulations.gov U.S.C. 1371(a)(5)(A)) directs the Mammals; Taking Marine Mammals without change. All personal identifying Secretary of Commerce to allow, upon Incidental to Southeast Fisheries information (e.g., name, address), request, the incidental, but not Science Center and Texas Parks and confidential business information, or intentional taking of small numbers of Wildlife Department Fisheries otherwise sensitive information marine mammals by U.S. citizens who Research submitted voluntarily by the sender will engage in a specified activity (other than commercial fishing) within a specified AGENCY: National Marine Fisheries be publicly accessible. NMFS will Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and accept anonymous comments (enter geographical region for up to five years if, after notice and public comment, the Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), ‘‘N/A’’ in the required fields if you wish agency makes certain findings and Commerce. -

Print 1990-05-14 Symp Artificial Reefs for Management of Marine

INDONESIA'S EXPERIENCE OF FISH AGGREGATING DEVICES (FADS) BY HARDJONO' 1. INTRODUCTION As an archipelagic state, Indonesia is endowed with a vast area of marine waters amounting to 5.8 million km, comprising 2.8 million km of internal waters, 0.3 million km of territorial waters, and 2.7 million km of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Large areas of marine waters in Indonesia offer good resource potential typical of the tropics and marine fisheries play an important role in the Indonesia fisheries. Among the multispecies tropical resources available in Indonesia waters those of great value are skipjack, tuna, promfret, Spanish mackerel, snapper, grouper and some carangids. Among shellfish, shrimp (Penaeus sp.) and spiny lobster are the most expensive. Recent estimates of the fisheries potentials of the country indicate a.potentia1 reaching 6.6 million mt, comprising of 4.5 million mt ib archipelagic and territorial waters and 2.1 million mt in the EEZ. The development of marine fish production in Indonesia during the the years 1980-1987 shows an average increase of 6.22% a year. At present marine fisheries contribute 76% of the total fisheries production which by 1987 reached 2.017 million mt. As a result of diverse characteristics of the Indonesian archipelago, the country's marine fisheries are complex and varied, and are dominated by traditional fishing activities operating a large number of very small vessels. Various kinds of fishing gear are employed which are dominated by gill nets comprising nearly one third of all fishing units operated. When the amount of fish landed by different types of fishing gear is considered, payang: and purse seine contribute the largest part of fish landed amounting to about 26% of total annual fish landings. -

Aquatic Animal Welfare in U.S Fish Culture

AQUATIC ANIMAL WELFARE IN U.S FISH CULTURE F. S. Conte Department of Animal Science University of California Davis 60th Annual Northwest Fish Culture Conference Redding, CA December 1-3, 2009 Animal Rights People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) http://www.animalactivist.com/ Animal Rights & Animal Welfare Animal Rights: A philosophy that animals have the same rights as people. Objective: to end the use of animals as companions and pets, and in extreme cases, opposition to the use of animals for food, fiber, entertainment and medical research. Animal Welfare: Concern for the well-being of individual animals, unrelated to the perceived rights of the animal or the ecological dynamics of the species. The position usually focuses on the morality of human action (or inaction), as opposed to making deeper political or philosophical claims about the status of animals Fish Welfare: A challenge to the feeling-based approach, with implications to recreational fisheries Table 1 Implications of animal welfare, animal liberation and animal rights concepts for the socially accepted interaction of humans with fish. Animal welfare Animal Animal Criteria liberation rights Fish have intrinsic value Yes/No No Yes Fish have rights No No Yes Duties towards fish Yes Yes Yes Catch, kill and eat Yes No No Regulatory catch-and-release Yes No No Voluntary catch-and-release Yes No No Recreational fishing Yes No No Fishery management Yes No No Use of animals (food, work, Yes No No manufacture, recreation and science) Robert Arlinghaus, Steven J. Cooke, Alexander Schwab & Ian G. Cowx. Fish and Fisheries, 2007, 8, 57-71. -

2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 20062006 NationalNational SurveySurvey ofof Fishing,Fishing, Hunting,Hunting, andand Wildlife-AssociatedWildlife-Associated RecreationRecreation FHW/06-NAT 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of Commerce Dirk Kempthorne, Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary Secretary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Economics and Statistics Administration H. Dale Hall, Cynthia A. Glassman, Director Under Secretary for Economic Affairs U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Charles Louis Kincannon, Director U.S. Department of the Interior Economics and Statistics Dirk Kempthorne, Administration Secretary Cynthia A. Glassman, Under Secretary for Economic Affairs U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service H. Dale Hall, Director U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Charles Louis Kincannon, Director Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Rowan Gould, Assistant Director The U.S. Department of the Interior protects and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage; provides scientifi c and other information about those resources; and honors its trust responsi- bilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affi liated Island Communities. The mission of the Department’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fi sh, wildlife, and their habitats for the continuing benefi t of the American people. The Service is responsible for national programs of vital importance to our natural resources, including administration of the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Programs. These two programs provide fi nan- cial assistance to the States for projects to enhance and protect fi sh and wildlife resources and to assure their availability to the public for recreational purposes. -

EIFAAC International Symposium Recreational Fishing in an Era of Change Lillehammer, Norway 14 – 17 June 2015

REPORT M-369 | 2015 EIFAAC International Symposium Recreational fishing in an era of change Lillehammer, Norway 14 – 17 June 2015 COLOPHON Executive institution Norwegian Environment Agency Project manager for the contractor Contact person in the Norwegian Environment Agency Øystein Aas Arne Eggereide M-no Year Pages Contract number 369 2015 70 Publisher The project is funded by Norwegian Environment Agency, NINA, NASCO, Norwegian Environment Agency EIFAAC Registration Fees Author(s) Øystein Aas (editor) Title – Norwegian and English EIFAAC International Symposium - Recreational fishing in an era of change. Symposium Program and Abstracts. Summary – sammendrag Norway host an international symposium on recreational fisheries initiated and organised through the European Inland Fisheries and Aquaculture Advisory Commission (EIFAAC), in Lillehammer, 14 – 17 June 2015. Nearly 200 participants from around 20 countries have registered for the meeting. This report presents the full program of the Symposium, including abstracts for the more than 100 presentations given at the meeting. 4 emneord 4 subject words Konferanse, fritidsfiske, EIFAAC, program Conference, programme, EIFAAC, angling Front page photo Øystein Aas 2 EIFAAC International Symposium | M-369 | 2015 Content 1. Preface ....................................................................................................... 4 2. Symposium organisation ................................................................................... 5 3. Supporters and sponsors .................................................................................. -

Official Rules for Georgia Saltwater Gamefish Record Submission

GEORGIA SALTWATER GAMEFISH RECORDS ANGLING RULES Angling rules associated with Georgia's Saltwater Gamefish Records Program are patterned largely after saltwater rules established by the International Game Fish Association. Subtle and obvious modifications, such as the lack of line classes in Georgia regulations, do exist. Each angler should carefully review each set of rules to discern these differences. Only fish landed in accordance with program rules outlined below and within the intent of these rules will be eligible for status as a Georgia Saltwater Gamefish Record. Like IGFA, the Georgia program is designed to recognize not only the fighting abilities of fishermen and their quarry, but also to promote ethical, sporting angling practices and a greater appreciation of coastal resources. In light of these considerations, each fisherman must determine whether his achievement reflects the intent and the spirit of these standards. Rules alone cannot ensure that angling experiences equal the catch, or vice versa. A. SAFETY Anglers must consider several factors in the pursuit of a Georgia Saltwater Gamefish Record. Primary among these is safety for the angler, crew, and/or vessel. Fishermen should carefully weigh safety demands against the inherent risks associated with certain gamefish, such as sharks, billfish, and other large species. It is ultimately the decision of the angler (and vessel captain, if applicable) to decide whether the catch can be safely accomplished under the existing circumstances and with the knowledge and equipment available. B. LINE 1. Monofilament, multifilalment, and lead core multifilament lines may be used. 2. Wire lines are prohibited. C. DOUBLE LINE AND LINE BACKING The use of a double line is not required. -

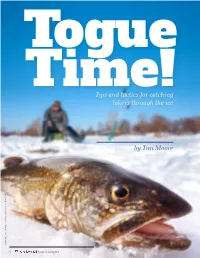

Tips and Tactics for Catching Lakers Through the Ice by Tim Moore

Togue Time!Tips and tactics for catching lakers through the ice by Tim Moore STOCKPHOTO.COM i © LEMONADE LUCY / FEDBUL - COMPOSITE IMAGE 4 January / February 2018 he crisp air, the frozen surface of a lake, the One day, while out with a group of ice anglers on Lake Tsilence broken only by the sound of ice augers Winnipesaukee, we began the trip jigging. The previous day, we had and snowmobiles, and the challenge of pursuing New done well jigging in this same Hampshire’s largest wild trout species. These are spot, and I felt confident that this day would be no different. A few some of the things that inspire ice anglers to get out lakers showed some interest early, onto New Hampshire’s frozen lakes each winter to but no takers. Then it was as if they had vanished. I was hesitant catch lake trout through the ice. to abandon such a consistent loca- tion, so I decided to try a couple Togue, laker, namaycush – whatever you call them, lake trout tip-ups with live smelt. Before I could get the second tip-up provide great fishing action through the ice during the long in the water, the flag went up on the first! I spent the next winter months in New Hampshire. few hours cycling between the two tip-ups. The action was As soon as the season opens and the ice is safe enough to non-stop. Later that afternoon, everything changed, and we fish, anglers from around New England flock to lakes such as were back to jigging.