Fish Welfare in Recreational Fishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dewey Gillespie's Hands Finish His Featherwing

“Where The Rivers Meet” The Fly Tyers of New Brunswi By Dewey Gillespie The 2nd Time Around Dewey Gillespie’s hands finish his featherwing version of NB Fly Tyer, Everett Price’s “Rose of New England Streamer” 1 Index A Albee Special 25 B Beulah Eleanor Armstrong 9 C Corinne (Legace) Gallant 12 D David Arthur LaPointe 16 E Emerson O’Dell Underhill 34 F Frank Lawrence Rickard 20 G Green Highlander 15 Green Machine 37 H Hipporous 4 I Introduction 4 J James Norton DeWitt 26 M Marie J. R. (LeBlanc) St. Laurent 31 N Nepisiguit Gray 19 O Orange Blossom Special 30 Origin of the “Deer Hair” Shady Lady 35 Origin of the Green Machine 34 2 R Ralph Turner “Ralphie” Miller 39 Red Devon 5 Rusty Wulff 41 S Sacred Cow (Holy Cow) 25 3 Introduction When the first book on New Brunswick Fly Tyers was released in 1995, I knew there were other respectable tyers that should have been including in the book. In absence of the information about those tyers I decided to proceed with what I had and over the next few years, if I could get the information on the others, I would consider releasing a second book. Never did I realize that it would take me six years to gather that information. During the six years I had the pleasure of personally meeting a number of the tyers. Sadly some of them are no longer with us. During the many meetings I had with the fly tyers, their families and friends I will never forget their kindness and generosity. -

Fishing Tackle Related Items

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF FISHING TACKLE and RELATED ITEMS at the CROSFIELD HALL BROADWATER ROAD ROMSEY, HANTS SO51 8GL on SATURDAY, 10th April 2021 at 12 noon 1 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) All Lots are offered for sale as shown and neither A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. VAT is payable on the Hammer Price. The Buyer shall pay the Auctioneer a premium of VAT is payable at the rates prevailing on the date of 18% of the Hammer Price (together with VAT at the auction. -

IGFA Angling Rules

International Angling Rules The following angling rules have been formulated by the International Game Fish Association to promote ethical and sporting angling practices, to establish uniform regulations for the compilation of world game fish records, and to provide basic angling guidelines for use in fishing tournaments and any other group angling activities. The word “angling” is defined as catching or attempting to catch fish with a rod, reel, line, and hook as outlined in the international angling rules. There are some aspects of angling that cannot be controlled through rule making, however. Angling regulations cannot insure an outstanding performance from each fish, and world records cannot indicate the amount of difficulty in catching the fish. Captures in which the fish has not fought or has not had a chance to fight do not reflect credit on the fisherman, and only the angler can properly evaluate the degree of achievement in establishing the record. Only fish caught in accordance with IGFA international angling rules, and within the intent of these rules, will be considered for world records. Following are the rules for freshwater and saltwater fishing and a separate set of rules for fly fishing. RULES FOR FISHING IN FRESH AND SALT WATER (Also see Rules for Fly fishing) E. ROD Equipment Regulations 1. Rods must comply with sporting ethics and customs. A. LINE Considerable latitude is allowed in the choice of a rod, but rods giving 1. Monofilament, multifilament, and lead core multifilament the angler an unfair advantage will be disqualified. This rule is lines may be used. For line classes, see World Record Requirements. -

Best Practices for Catch-And-Release Recreational Fisheries – Angling Tools and Tactics

G Model FISH-4421; No. of Pages 13 ARTICLE IN PRESS Fisheries Research xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fisheries Research j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fishres Best practices for catch-and-release recreational fisheries – angling tools and tactics a,∗ b a Jacob W. Brownscombe , Andy J. Danylchuk , Jacqueline M. Chapman , a a Lee F.G. Gutowsky , Steven J. Cooke a Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Ottawa-Carleton Institute for Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Dr., Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada b Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 160 Holdsworth Way, Amherst, MA 01003 USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Catch-and-release angling is an increasingly popular conservation strategy employed by anglers vol- Received 12 October 2015 untarily or to comply with management regulations, but associated injuries, stress and behavioural Received in revised form 19 April 2016 impairment can cause post-release mortality or fitness impairments. Because the fate of released fish Accepted 30 April 2016 is primarily determined by angler behaviour, employing ‘best angling practices’ is critical for sustain- Handled by George A. Rose able recreational fisheries. While basic tenants of best practices are well established, anglers employ a Available online xxx diversity of tactics for a range of fish species, thus it is important to balance science-based best practices with the realities of dynamic angler behaviour. Here we describe how certain tools and tactics can be Keywords: Fishing integrated into recreational fishing practices to marry best angling practices with the realities of angling. -

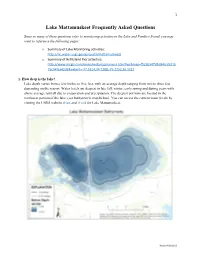

Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions

1 Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions Since so many of these questions refer to monitoring activities in the Lake and Pamlico Sound, you may want to reference the following pages: o Summary of Lake Monitoring activities: http://nc.water.usgs.gov/projects/mattamuskeet/ o Summary of Bell Island Pier activities: http://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=f52ab347d5e84ccc921b 75c34fea42d5&extent=-77.5214,34.7208,-75.2252,36.3212 1. How deep is the lake? Lake depth varies from a few inches to five feet, with an average depth ranging from two to three feet depending on the season. Water levels are deepest in late fall, winter, early spring and during years with above average rainfall due to evaporation and precipitation. The deepest portions are located in the northwest portion of the lake. (see bathymetric map below). You can access the current water levels by visiting the USGS website (East and West) for Lake Mattamuskeet. Updated 10/12/16 2 2. Why is the lake so high/low? Lake levels fluctuate on a daily, seasonal and yearly basis. Water levels are primarily determined by climatic conditions. Generally, seasonal lake levels follow a pattern of being lower in the summer due to high evaporation rates and higher in fall, winter and spring due to lower evaporation rates and greater precipitation. Lake levels will increase by a few inches after a heavy rain. During wet years with lots of precipitation, water levels will rise; during drought years, water levels will fall. You can access current water levels by visiting the USGS website for Lake Mattamuskeet (East and West). -

2020 Journal

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Physiological Impacts of Catch-And-Release Angling Practices on Largemouth Bass and Smallmouth Bass

Physiological Impacts of Catch-and-Release Angling Practices on Largemouth Bass and Smallmouth Bass STEVEN J. COOKE1 Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois and Center for Aquatic Ecology, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, Illinois 61820, USA JASON F. S CHREER Department of Biology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada DAVID H. WAHL Kaskaskia Biological Station, Center for Aquatic Ecology, Illinois Natural History Survey, RR #1, Post Office Box 157, Sullivan, Illinois 61951, USA DAVID P. P HILIPP Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois and Center for Aquatic Ecology, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, Illinois 61820, USA Abstract.—We conducted a series of experiments to assess the real-time physiological and behavioral responses of largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides and smallmouth bass M. dolomieu to different angling related stressors and then monitored their recovery using both cardiac output devices and locomotory activity telemetry. We also review our current understanding of the effects of catch-and-release angling on black bass and provide direction for future research. Collectively our data suggest that all angling elicits a stress response, however, the magnitude of this response is determined by the degree of exhaustion and varies with water temperature. Our results also suggest that air exposure, especially following exhaustive exercise, places an additional stress on fish that increases the time needed for recovery and likely the probability of death. Simulated tournament conditions revealed that metabolic rates of captured fish increase with live-well densities greater than one individual, placing a greater demand on live-well oxygen conditions. -

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

How to Match Your Catch to the Season

The Dish 06.05.2018 ild garlic and British springtime: Scottish variegated mint are lobster, turbot, sea trout, plaice, sprouting on the brill and crab. “It’s nice to look Wriverbank and forward to the seasons,” says Rex swallows swoop overhead. My HOW TO Goldsmith, the owner, who waders aren’t wet yet. Instead, celebrates the arrival of spring Stuart Wardle is teaching me the by roasting the first trout of the importance of reading the river. year, serving it with Jersey royals, “There’s no point fishing where M ATC H new-season asparagus and there aren’t any fish,” the expert homemade mayonnaise. angler points out, as we happily Most of the fish in Goldsmith’s tramp along the bank looking for display have recently finished clues — a hatch of mayflies or YOUR their spawning season, and are birds divebombing for insects now back on his counter after bobbing on the water. months of absence. For a lot of “Everything in nature is linked,” native British species, the mating Wardle explains. Warm weather CATC H period falls over the start of the coaxes insects out of hibernation. year, which is why May signals a They feed on the new leaves, and springtime bounty — the fish have they, in turn, become a juicy meal finished replenishing their stocks for the fish. “I look forward to TO THE and are in prime condition for every season, but there’s the table. something special about late “You don’t want to eat fish spring — everything is bursting during the spawning season. -

Release Recreational Angling to Effectively Conserve Diverse Fishery

Biodiversity and Conservation 14: 1195–1209, 2005. Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10531-004-7845-0 Do we need species-specific guidelines for catch-and- release recreational angling to effectively conserve diverse fishery resources? STEVEN J. COOKE1,* and CORY D. SUSKI2 1Department of Forest Sciences, Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, 2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4; 2Department of Biology, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada K7L 3N6; *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Received 2 April 2003; accepted in revised form 12 January 2004 Key words: Catch-and-release, Fisheries conservation, Hooking mortality, Recreational angling, Sustainable fisheries Abstract. Catch-and-release recreational angling has become very popular as a conservation strategy and as a fisheries management tool for a diverse array of fishes. Implicit in catch-and-release angling strategies is the assumption that fish experience low mortality and minimal sub-lethal effects. Despite the importance of this premise, research on this topic has focused on several popular North American sportfish, with negligible efforts directed towards understanding catch-and-release angling effects on alternative fish species. Here, we summarise the existing literature to develop five general trends that could be adopted for species for which no data are currently available: (1) minimise angling duration, (2) minimise air ex- posure, (3) avoid angling during extremes in water temperature, (4) use barbless hooks and artificial lures=flies, and (5) refrain from angling fish during the reproductive period. These generalities provide some level of protection to all species, but do have limitations. Therefore, we argue that a goal of conservation science and fisheries management should be the creation of species-specific guidelines for catch-and-release. -

Programme and Abstracts THANKS to OUR SPONSORS!

5th Pan-European Duck Symposium 16th-20th April 2018 Isle of Great Cumbrae, Scotland Programme and Abstracts THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS! 2 ORGANISING COMMITTEE Chris Waltho (Independent Researcher) Colin A Galbraith (Colin Galbraith Environment Consultancy) Richard Hearn (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust / Duck Specialist Group) Matthieu Guillemain (Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage / Duck Specialist Group) SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Tony Fox (University of Aarhus) Colin A Galbraith (Colin Galbraith Environment Consultancy) Andy J Green (Estación Biológica de Doñana) Matthieu Guillemain (Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage / DSG) Richard Hearn (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust / Duck Specialist Group) Sari Holopainen (University of Helsinki) Mika Kilpi (Novia University of Applied Sciences) Carl Mitchell (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust) David Rodrigues (Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra) Diana Solovyeva (Russian Academy of Sciences) Chris Waltho (Independent Researcher) 3 PROGRAMME Monday 16th April: Pre- meeting Workshop on marine issues 11.00 – 16.00. DAY1 (Tuesday 17th April) Chair: Chris Waltho 9:00 – 9:05 Chris Waltho – Welcome. 9:05 – 9:10 Provost Ian Clarkson - North Ayrshire Council. 9:10 – 9:20 Lady Isobel Glasgow - Chair of the Clyde Marine Planning Partnership. 9:20 – 9:30 Colin Galbraith – The aims and objectives of the Conference. 9:30 – 10:20 Plenary 1 Dr. Jacques Trouvilliez, (Executive Secretary of the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA)) 10:20 - 10:45 Coffee break SESSION 1 POPULATION DYNAMICS AND TRENDS Chair: Colin Galbraith 10:45 – 11:00 New pan-European data on the breeding distribution of ducks. Verena Keller, Martí Franch, Sergi Herrando, Mikhail Kalyakin, Olga Voltzit and Petr Voříšek 11:00 – 11:15 Trends in breeding waterbird guild richness in the southwestern Mediterranean: an analysis over 12 years (2005-2017). -

Kayaking and Fishing Go Together - Go out for a Paddle and Bring Home Some Fish for “Your Dinner…

kayak fishing safetyWORDS & IMAGES: Derek Hairon of Jersey Kayak Adventures [except where stated] Photo: Mark Rainsley Kayaking and fishing go together - go out for a paddle and bring home some fish for “your dinner… The massive growth of kayak fishing using sit on top new skills if you are to use the craft safely. Do not assume kayaks is resulting in many people taking up kayaking that just because you are an experienced angler or with little knowledge of” key safety skills. paddler that you can simply go out and start fishing. That's the theory. The reality is different. Whether you are Before you consider kayak fishing ensure you have a a competent kayaker or angler by linking the two sports good foundation of basic kayak skills. I see far too many together you create a lot of issues which impact upon sit on top anglers who are learning the hard way when a your safety afloat once you start fishing from a sit on bit of training would have fast tracked their development top kayak. The massive growth of kayak fishing using and enjoyment. Sign up for a sit-on-top kayak safety sit on top kayaks is resulting in many people taking up clinic or kayak fishing course. That way you can learn kayaking with little knowledge of key safety skills. Forget quickly and safely and avoid making potentially costly the marketing hype that portrays the kayak as an easy mistakes when selecting equipment. craft to fish from. Ditch this idea and any thoughts that you can simply transfer shore or boat based fishing skills If you are kayak fishing on the sea enrol on one of the over to the kayak without modification.