Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Preliminary Manatee Mortality Table with 5-Year Summary From: 01/01/2019 To: 11/22/2019

FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION MARINE MAMMAL PATHOBIOLOGY LABORATORY 2019 Preliminary Manatee Mortality Table with 5-Year Summary From: 01/01/2019 To: 11/22/2019 County Date Field ID Sex Size Waterway City Probable Cause (cm) Nassau 01/01/2019 MNE19001 M 275 Nassau River Yulee Natural: Cold Stress Hillsborough 01/01/2019 MNW19001 M 221 Hillsborough Bay Apollo Beach Natural: Cold Stress Monroe 01/01/2019 MSW19001 M 275 Florida Bay Flamingo Undetermined: Other Lee 01/01/2019 MSW19002 M 170 Caloosahatchee River North Fort Myers Verified: Not Recovered Manatee 01/02/2019 MNW19002 M 213 Braden River Bradenton Natural: Cold Stress Putnam 01/03/2019 MNE19002 M 175 Lake Ocklawaha Palatka Undetermined: Too Decomposed Broward 01/03/2019 MSE19001 M 246 North Fork New River Fort Lauderdale Natural: Cold Stress Volusia 01/04/2019 MEC19002 U 275 Mosquito Lagoon Oak Hill Undetermined: Too Decomposed St. Lucie 01/04/2019 MSE19002 F 226 Indian River Fort Pierce Natural: Cold Stress Lee 01/04/2019 MSW19003 F 264 Whiskey Creek Fort Myers Human Related: Watercraft Collision Lee 01/04/2019 MSW19004 F 285 Mullock Creek Fort Myers Undetermined: Too Decomposed Citrus 01/07/2019 MNW19003 M 275 Gulf of Mexico Crystal River Verified: Not Recovered Collier 01/07/2019 MSW19005 M 270 Factory Bay Marco Island Natural: Other Lee 01/07/2019 MSW19006 U 245 Pine Island Sound Bokeelia Verified: Not Recovered Lee 01/08/2019 MSW19007 M 254 Matlacha Pass Matlacha Human Related: Watercraft Collision Citrus 01/09/2019 MNW19004 F 245 Homosassa River Homosassa -

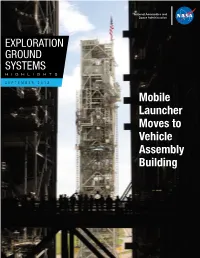

Mobile Launcher Moves to Vehicle Assembly Building EGS MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS

National Aeronautics and Space Administration EXPLORATION GROUND SYSTEMS HIGHLIGHTS SEPTEMBER 2018 Mobile Launcher Moves to Vehicle Assembly Building EGS MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS 3 Mobile launcher on the move 4 In the driver’s seat 5 Prepping for Underway Recovery Test 7 6 Employees, guests view ML move MOBILE LAUNCHER ON THE MOVE NASA’s mobile launcher is inside High Bay 3 at the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on Sept. 11, 2018, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Photo credit: NASA/Frank Michaux NASA’s mobile launcher, atop crawler-transporter 2, traveled from Launch Pad 39B to the Vehicle Assembly Building at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, on Sept. 7, 2018. Arriving late in the afternoon, the mobile launcher stopped at the entrance to the VAB. Early the next day, Sept. 8, engineers and technicians rotated and extended the crew access arm near the top of the mobile launcher tower. Then the mobile launcher was moved inside High Bay 3, where it will spend about seven months undergoing verification and validation testing with the 10 levels of new work platforms, ensuring that it can provide support to the agency’s Space Launch System (SLS). The 380-foot-tall structure is equipped with the crew access Cliff Lanham, NASA project manager for the mobile launcher, takes a break arm and several umbilicals that will provide power, environmental to attend the employee event for the mobile launcher move to the Vehicle control, pneumatics, communication and electrical connections Assembly Building on Sept. 7, 2018, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. -

093Tit-Wildlife Adventures Map-Pad 1.Indd

Find Your Launch Point. START ANYWHERE. north GO EVERYWHERE. 1 Mosquito 95 Lagoon 1 WILDLIFE ADVENTURE POINTS | START EXPLORING HERE | 3 Canaveral National 1 Turnbull Creek 2 Seashore 2 Scottsmoor Landing To Orlando-Sanford 4 International Airport 3 Mosquito 3 Haulover Canal & Lagoon Manatee Observation Deck Indian River 46 5 4 Klondike Beach 8 5 Playalinda Beach Buck Lake 95 6 Conservation 6 Eddy Creek St. Johns Area 1 9 7 River WY 46 Atlantic Ocean 7 Bio Lab Road 406 10 Seminole X BREWER PK 402 Ranch MA 12 8 Scrub Ridge Trail Conservation Titusville Parrish Marina Park Merritt Area Island 3 9 Black Point Wildlife Drive National Hatbill Park Wildlife 11 Apollo/Saturn V Refuge Center 10 Oak Hammock & Palm Hammock Trails Your Adventure 13 405 VAB 11 Gator Creek Road & Begins Here Peacocks Pocket Road For Info and Other Maps, or to Rent a Bicycle, WELCOME Stop at the Downtown Welcome Center! CENTER 50 Kennedy 12 MINWR Visitor Center Orlando Space Wetlands Park 14 Center 13 Fox Lake Sanctuary & Park* 50 15 NASA PKWY Space Coast 405 14 Blue Heron Wetlands Regional Airport Kennedy 520 Valiant Air Space Center 15 Enchanted Forest* Command Visitor Complex Warbird Museum Cycling Trails 407 To Orlando Indian *Brevard County Environmentally River Banana Endangered Lands Program International River Airport 528 1 95 LAUNCH WY 3 FROM SOM PK HERE PORT CANAVERAL GRIS • 520 To Orlando-Melbourne International Airport 528 COCOA BEACH A1A • THE BEST OF NATURAL FLORIDA & UNFORGETTABLE WILDLIFE EXPERIENCES AWAIT. #LAUNCHFROMHERE 1 Turnbull Creek | At times a narrow creek with winding turns, it native peoples saw when they lived here hundreds of years ago. -

SPORT FISH of OHIO Identification DIVISION of WILDLIFE

SPORT FISH OF OHIO identification DIVISION OF WILDLIFE 1 With more than 40,000 miles of streams, 2.4 million acres of Lake Erie and inland water, and 450 miles of the Ohio River, Ohio supports a diverse and abundant fish fauna represented by more than 160 species. Ohio’s fishes come in a wide range of sizes, shapes and colors...and live in a variety of aquatic habitats from our largest lakes and rivers to the smallest ponds and creeks. Approximately one-third of these species can be found in this guide. This fish identification guide provides color illustrations to help anglers identify their catch, and useful tips to help catch more fish. We hope it will also increase your awareness of the diversity of fishes in Ohio. This book also gives information about the life history of 27 of Ohio’s commonly caught species, as well as information on selected threatened and endangered species. Color illustrations and names are also offered for 20 additional species, many of which are rarely caught by anglers, but are quite common throughout Ohio. Fishing is a favorite pastime of many Ohioans and one of the most enduring family traditions. A first fish or day shared on the water are memories that last a lifetime. It is our sincere hope that the information in this guide will contribute significantly to your fishing experiences and understanding of Ohio’s fishes. Good Fishing! The ODNR Division of Wildlife manages the fisheries of more than 160,000 acres of inland water, 7,000 miles of streams, and 2.25 million acres of Lake Erie. -

Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region

$10 $10 PB1785 PB1785 Invasive Weeds Invasive Weeds of the of the Appalachian Appalachian Region Region i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………...i How to use this guide…………………………………ii IPM decision aid………………………………………..1 Invasive weeds Grasses …………………………………………..5 Broadleaves…………………………………….18 Vines………………………………………………35 Shrubs/trees……………………………………48 Parasitic plants………………………………..70 Herbicide chart………………………………………….72 Bibliography……………………………………………..73 Index………………………………………………………..76 AUTHORS Rebecca M. Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, The University of Tennessee Gregory R. Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Specialist for Invasive Weeds, The University of Tennessee Robert J. Richardson, Assistant Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, North Caro- lina State University G. Neil Rhodes, Jr., Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, The University of Ten- nessee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank all the individuals and organizations who have contributed their time, advice, financial support, and photos to the crea- tion of this guide. We would like to specifically thank the USDA, CSREES, and The Southern Region IPM Center for their extensive support of this pro- ject. COVER PHOTO CREDITS ii 1. Wavyleaf basketgrass - Geoffery Mason 2. Bamboo - Shawn Askew 3. Giant hogweed - Antonio DiTommaso 4. Japanese barberry - Leslie Merhoff 5. Mimosa - Becky Koepke-Hill 6. Periwinkle - Dan Tenaglia 7. Porcelainberry - Randy Prostak 8. Cogongrass - James Miller 9. Kudzu - Shawn Askew Photo credit note: Numbers in parenthesis following photo captions refer to the num- bered photographer list on the back cover. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Tabs: Blank tabs can be found at the top of each page. These can be custom- ized with pen or marker to best suit your method of organization. Examples: Infestation present On bordering land No concern Uncontrolled Treatment initiated Controlled Large infestation Medium infestation Small infestation Control Methods: Each mechanical control method is represented by an icon. -

Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions

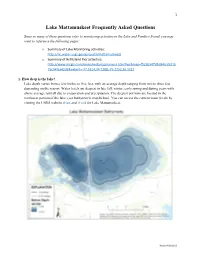

1 Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions Since so many of these questions refer to monitoring activities in the Lake and Pamlico Sound, you may want to reference the following pages: o Summary of Lake Monitoring activities: http://nc.water.usgs.gov/projects/mattamuskeet/ o Summary of Bell Island Pier activities: http://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=f52ab347d5e84ccc921b 75c34fea42d5&extent=-77.5214,34.7208,-75.2252,36.3212 1. How deep is the lake? Lake depth varies from a few inches to five feet, with an average depth ranging from two to three feet depending on the season. Water levels are deepest in late fall, winter, early spring and during years with above average rainfall due to evaporation and precipitation. The deepest portions are located in the northwest portion of the lake. (see bathymetric map below). You can access the current water levels by visiting the USGS website (East and West) for Lake Mattamuskeet. Updated 10/12/16 2 2. Why is the lake so high/low? Lake levels fluctuate on a daily, seasonal and yearly basis. Water levels are primarily determined by climatic conditions. Generally, seasonal lake levels follow a pattern of being lower in the summer due to high evaporation rates and higher in fall, winter and spring due to lower evaporation rates and greater precipitation. Lake levels will increase by a few inches after a heavy rain. During wet years with lots of precipitation, water levels will rise; during drought years, water levels will fall. You can access current water levels by visiting the USGS website for Lake Mattamuskeet (East and West). -

Water Resources Brevard County, Florida

STATE OF FLORIDA STATE BOARD OF CONSERVATION DIVISION OF GEOLOGY FLORIDA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Robert O. Vernon, Director REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO. 28 WATER RESOURCES OF BREVARD COUNTY, FLORIDA By D. W. Brown, W. E. Kenner, J. W. Crooks, and J. B. Foster U. S. Geological Survey Prepared by the UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY in cooperation with the CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN FLORIDA FLOOD CONTROL DISTRICT the U. S. ARMY, CORPS OF ENGINEERS and the. FLORIDA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TALLAHASSEE 1962 /AJ.z7s FLORIDA STATE BOA ~"• OF CONSERVATION FARRIS BRYANT Governor TOM ADAMS J. EDWIN LARSON Secretary of State Treasurer THOMAS D. BAILEY RICHARD ERVIN Stperintendent of Public Instruction Attorney General RAY E. GREEN DOYLE CONNER Comptroller Commissioner of Agriculture W. RANDOLPH HODGES Director . ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Qfo'ida Ge)oloqicaf 5 urvej January 11, 1962 Honorable Farris Bryant, Chairman Florida State Board of Conservation Tallahassee, Florida Dear Governor Bryant: The Florida Geological Survey is pleased to publish as Report of In- vestigations No. 28, a comprehensive study of the water resources of Brevard County. This report was prepared by Messrs. D. W. Brown, W. E. Kenner, J. W. Crooks, and J. B. Foster, of the U. S. Geological Survey, in cooperation with the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control District; U. S. Army, Corps of Engineers; and the Florida Geological Survey. This is a very timely study, since the development of adequate supplies of fresh water and the prevention and alleviation of flooding are the principal water problems in Brevard County. The rapid expansion of popu- lation and the development of new industries associated with the space effort have made large demands for increased supplies of fresh water, particularly in the Atlantic Coastal Ridge area on Merritt Island and in the barrier beach area. -

AEG-ANR House Offer #1

Conference Committee on Senate Agriculture, Environment, and General Government Appropriations/ House Agriculture & Natural Resources Appropriations Subcommittee House Offer #1 Budget Spreadsheet Proviso and Back of the Bill Implementing Bill Saturday, April 17, 2021 7:00PM 412 Knott Building Conference Spreadsheet AGENCY House Offer #1 SB 2500 Row# ISSUE CODE ISSUE TITLE FTE RATE REC GR NR GR LATF NR LATF OTHER TFs ALL FUNDS FTE RATE REC GR NR GR LATF NR LATF OTHER TFs ALL FUNDS Row# 1 AGRICULTURE & CONSUMER SERVICES 1 2 1100001 Startup (OPERATING) 3,740.25 162,967,107 103,601,926 102,876,093 1,471,917,888 1,678,395,907 3,740.25 162,967,107 103,601,926 102,876,093 1,471,917,888 1,678,395,907 2 1601280 4,340,000 4,340,000 4,340,000 4,340,000 Continuation of Fiscal Year 2020-21 Budget Amendment Dacs- 3 - - - - 3 037/Eog-B0514 Increase In the Division of Licensing 1601700 Continuation of Budget Amendment Dacs-20/Eog #B0346 - 400,000 400,000 400,000 400,000 4 - - - - 4 Additional Federal Grants Trust Fund Authority 5 2401000 Replacement Equipment - - 6,583,594 6,583,594 - - 2,624,950 2,000,000 4,624,950 5 6 2401500 Replacement of Motor Vehicles - - 67,186 2,789,014 2,856,200 - - 1,505,960 1,505,960 6 6a 2402500 Replacement of Vessels - - 54,000 54,000 - - - 6a 7 2503080 Direct Billing for Administrative Hearings - - (489) (489) - - (489) (489) 7 33N0001 (4,624,909) (4,624,909) 8 Redirect Recurring Appropriations to Non-Recurring - Deduct (4,624,909) - (4,624,909) - 8 33N0002 4,624,909 4,624,909 9 Redirect Recurring Appropriations to Non-Recurring -

January 6, 1997 KSC Contact: Joel Wells KSC Release No

January 6, 1997 KSC Contact: Joel Wells KSC Release No. 1-97 Note to Editors/News Directors: KSC TO CELEBRATE GRAND OPENING OF APOLLO/SATURN V CENTER JAN. 8 On Wednesday, Jan. 8, news media representatives will have several opportunities to interview former Apollo astronauts, NASA and KSC officials, and Space Shuttle astronauts at the new Apollo/Saturn V Center. From 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. members of the media will be able to interview several former Apollo astronauts at the Apollo/Saturn V Center. Media interested in conducting interviews during this time block must contact Melissa Tomasso, KSC Visitor Center, at (407) 449-4254 by close of business on Jan. 7. She will schedule all interview appointments. Media members should arrive at the KSC Press Site 30 minutes before their scheduled interview time for transport to the Apollo/Saturn V Center. In addition, a formal grand opening gala is planned for Wednesday evening. Several Apollo astronauts will also be available for interview at 6 p.m. at the Apollo/Saturn V Center. Media interested in this opportunity must be at the KSC Press Site by 5:30 p.m. for transport to the new facility. Invited guests and media wishing to attend the gala at the regular time will meet at the KSC Visitor Center (KSCVC) between 6:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. for transport to the Apollo/Saturn V Center. A tour of the new facility’s shows and exhibits is included. A ceremony featuring presentations from NASA Administrator Dan Goldin, KSC Director Jay Honeycutt, and former astronauts John Young and Eugene Cernan will begin at 8 p.m. -

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's National Estuary Program

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Estuary Program Story Map Text-only File 1) Introduction Welcome to the National Estuary Program story map. Since 1987, the EPA National Estuary Program (NEP) has made a unique and lasting contribution to protecting and restoring our nation's estuaries, delivering environmental and public health benefits to the American people. This story map describes the 28 National Estuary Programs, the issues they face, and how place-based partnerships coordinate local actions. To use this tool, click through the four tabs at the top and scroll around to learn about our National Estuary Programs. Want to learn more about a specific NEP? 1. Click on the "Get to Know the NEPs" tab. 2. Click on the map or scroll through the list to find the NEP you are interested in. 3. Click the link in the NEP description to explore a story map created just for that NEP. Program Overview Our 28 NEPs are located along the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts and in Puerto Rico. The NEPs employ a watershed approach, extensive public participation, and collaborative science-based problem- solving to address watershed challenges. To address these challenges, the NEPs develop and implement long-term plans (called Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plans (link opens in new tab)) to coordinate local actions. The NEPs and their partners have protected and restored approximately 2 million acres of habitat. On average, NEPs leverage $19 for every $1 provided by the EPA, demonstrating the value of federal government support for locally-driven efforts. View the NEPmap. What is an estuary? An estuary is a partially-enclosed, coastal water body where freshwater from rivers and streams mixes with salt water from the ocean. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge BIRD LIST

Merrritt Island National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service P.O. Box 2683 Titusville, FL 32781 http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Merritt_Island 321/861 0669 Visitor Center Merritt Island U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD National Wildlife Refuge March 2019 Bird List photo: James Lyon Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, located just Seasonal Occurrences east of Titusville, shares a common boundary with the SP - Spring - March, April, May John F. Kennedy Space Center. Its coastal location, SU - Summer - June, July, August tropic-like climate, and wide variety of habitat types FA - Fall - September, October, November contribute to Merritt Island’s diverse bird population. WN - Winter - December, January, February The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee lists 521 species of birds statewide. To date, 359 You may see some species outside the seasons indicated species have been identified on the refuge. on this checklist. This phenomenon is quite common for many birds. However, the checklist is designed to Of special interest are breeding populations of Bald indicate the general trend of migration and seasonal Eagles, Brown Pelicans, Roseate Spoonbills, Reddish abundance for each species and, therefore, does not Egrets, and Mottled Ducks. Spectacular migrations account for unusual occurrences. of passerine birds, especially warblers, occur during spring and fall. In winter tens of thousands of Abundance Designation waterfowl may be seen. Eight species of herons and C – Common - These birds are present in large egrets are commonly observed year-round. numbers, are widespread, and should be seen if you look in the correct habitat. Tips on Birding A good field guide and binoculars provide the basic U – Uncommon - These birds are present, but because tools useful in the observation and identification of of their low numbers, behavior, habitat, or distribution, birds. -

1987 (5.2Mb Pdf)

1'4evvs National Aeronautics and Space Administration JohnF.KennedySpace Center Kennedy Space Center, Florida 32899 AC305 867-2468 , ... I For Release: David W. Garrett April 13, 1987 Headquarters, Washington, D.C. (Phone: 202/453-8400) RELEASE: 87-56 SHEEHAN NAMED ASSOCIATE AE_INISTRATOR FOR _NICATIONS William Sheehan has been appointed Associate Administrator for Cournnunications, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C., effective May 4, 1987. This new position, announced in February 1987, reflects the importance that NASA management places on full and complete communications within and outside the agency. Sheehan will be the principal advisor to the Administrator and Deputy Administrator on public affairs matters. He will be responsible for policy level management and direction of NASA's public affairs, television development and internal communications organizat ions. Sheehan comes to NASA from The Executive Television Workshop, Inc., where he was director of the Detroit office. Prior to this position he was executive director, Corporate Public Affairs, Ford Motor Co. and vice president Public Affairs, Ford Aerospace and Corrrnunications Corp., Detroit. In 1974, Sheehan was appointed president of ABC News, a position he held until 1977. He had held various positions at ABC since 1961 including five years as a national and foreign correspondent. He was a radio and television anchorman, labor reporter and chief of ABC News' London bureau between 1961 and 1966. In 1966, he returned to New York to become vice president, Television News,_"';iseni.o.r _ vice president and then president, ABC News. Recently, Sheehan has been/working in public television on the local and national level as chairman of the board of station WTVS of Detroit and is a member of the board of directors and on the executive committee of the Public Broadcasting Service.