FR-29-Kavieng.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kansas Fishing Regulations Summary

2 Kansas Fishing 0 Regulations 0 5 Summary The new Community Fisheries Assistance Program (CFAP) promises to increase opportunities for anglers to fish close to home. For detailed information, see Page 16. PURCHASE FISHING LICENSES AND VIEW WEEKLY FISHING REPORTS ONLINE AT THE DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND PARKS' WEBSITE, WWW.KDWP.STATE.KS.US TABLE OF CONTENTS Wildlife and Parks Offices, e-mail . Zebra Mussel, White Perch Alerts . State Record Fish . Lawful Fishing . Reservoirs, Lakes, and River Access . Are Fish Safe To Eat? . Definitions . Fish Identification . Urban Fishing, Trout, Fishing Clinics . License Information and Fees . Special Event Permits, Boats . FISH Access . Length and Creel Limits . Community Fisheries Assistance . Becoming An Outdoors-Woman (BOW) . Common Concerns, Missouri River Rules . Master Angler Award . State Park Fees . WILDLIFE & PARKS OFFICES KANSAS WILDLIFE & Maps and area brochures are available through offices listed on this page and from the PARKS COMMISSION department website, www.kdwp.state.ks.us. As a cabinet-level agency, the Kansas Office of the Secretary AREA & STATE PARK OFFICES Department of Wildlife and Parks is adminis- 1020 S Kansas Ave., Rm 200 tered by a secretary of Wildlife and Parks Topeka, KS 66612-1327.....(785) 296-2281 Cedar Bluff SP....................(785) 726-3212 and is advised by a seven-member Wildlife Cheney SP .........................(316) 542-3664 and Parks Commission. All positions are Pratt Operations Office Cheyenne Bottoms WA ......(620) 793-7730 appointed by the governor with the commis- 512 SE 25th Ave. Clinton SP ..........................(785) 842-8562 sioners serving staggered four-year terms. Pratt, KS 67124-8174 ........(620) 672-5911 Council Grove WA..............(620) 767-5900 Serving as a regulatory body for the depart- Crawford SP .......................(620) 362-3671 ment, the commission is a non-partisan Region 1 Office Cross Timbers SP ..............(620) 637-2213 board, made up of no more than four mem- 1426 Hwy 183 Alt., P.O. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 39/Wednesday, February 27, 2019

6576 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 39 / Wednesday, February 27, 2019 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Protected Resources, National Marine active acoustic survey sources. TPWD Fisheries Service, 1315 East-West has requested take of dolphins from four National Oceanic and Atmospheric Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910. stocks, by mortality or serious injury, Administration Instructions: Comments sent by any incidental to gillnet fishing in Texas other method, to any other address or bays. For both applicants, the 50 CFR Part 219 individual, or received after the end of regulations would be valid from 2018 to [Docket No. 161109999–8999–01] the comment period, may not be 2023. considered by NMFS. All comments Legal Authority for the Proposed Action RIN 0648–BG44 received are a part of the public record and will generally be posted for public Section 101(a)(5)(A) of the MMPA (16 Taking and Importing Marine viewing on www.regulations.gov U.S.C. 1371(a)(5)(A)) directs the Mammals; Taking Marine Mammals without change. All personal identifying Secretary of Commerce to allow, upon Incidental to Southeast Fisheries information (e.g., name, address), request, the incidental, but not Science Center and Texas Parks and confidential business information, or intentional taking of small numbers of Wildlife Department Fisheries otherwise sensitive information marine mammals by U.S. citizens who Research submitted voluntarily by the sender will engage in a specified activity (other than commercial fishing) within a specified AGENCY: National Marine Fisheries be publicly accessible. NMFS will Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and accept anonymous comments (enter geographical region for up to five years if, after notice and public comment, the Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), ‘‘N/A’’ in the required fields if you wish agency makes certain findings and Commerce. -

Health Situation Report 65 (Released: 22 March 2021; Report Period: 15 - 21 February 2021)

Papua New Guinea Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Health Situation Report #65 22 March 2021 Period of report: 15 - 21 March 2021 This Situation Report is jointly issued by PNG National Department of Health and World Health Organization once weekly. This Report is not comprehensive and covers information received as of reporting date. Situation Summary and Highlights ❒ As of 21 March 2021 (12:00 pm), there have been 3574 COVID-19 cases and 36 COVID-19 deaths reported in Papua New Guinea. From the period of 15 to 21 March, there were 1305 newly reported cases including 15 new deaths. This is the seventh consecutive week of increasing cases, and more than double the previous highest number of cases reported in a single week in PNG. ❒ The total number of provinces that have reported COVID-19 cases to date is twenty. Only Manus and Oro (Northern) Provinces have not reported cases to date. ❒ Public Health Unit at Doherty Institute in Australia has conducted whole genome sequencing on positive test samples sent from PNG and no variants of concern have been identified in sequencing conducted to date. ❒ The COVID-19 Hotline has experienced a 33.83% increase in calls since the last fortnight and the rate of health-related calls being referred to the Rapid Response Teams and PHAs has also increased by 33% from the prior week. ❒ This week the Australian government will deploy an Australian Medical Assistance Team (AUSMAT) to undertake assessments and Please note: Due to data cleaning, the number of critical planning for a potential full deployment cases may not add up exactly from last week. -

The Need for Premium Agri-Fisheries for the Disaster-Affected Areas of Leyte, Philippines

Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture 10: 76-90 ( 2015) The Need for Premium Agri-fisheries for the Disaster-Affected Areas of Leyte, Philippines Dora Fe H. Bernardo1*, Oscar B. Zamora2 and Lucille Elna P. de Guzman2 1 Institute ofBiological Sciences, College ofArts and Sciences, University ofthe Philippines Los Baños, College, Laguna 4031 Philippines 2 Crop Science Cluster, College ofAgriculture, University ofthe Philippines Los Baños, College, Laguna 4031 Philippines On 8 November 2013, Super Typhoon Yolanda (internationally, “Haiyan”), a category-five typhoon, traversed the central Philippines. It was reportedly the strongest recorded storm ever to hit land, with winds over 300 km h-1 and storm surges over 4 m around coastal towns ofthe central Philippines. Total losses fromthe storm were PHP 571.1 billion (USD 12.9 billion); the estimate for Leyte Province was PHP 9.4 billion. In Leyte, the typhoon almost totally destroyed most crops, fishing boats and gear, aquaculture infrastructure, seaweed farms, mangroves, onshore facilities, and markets. The Leyte Rehabilitation and Recovery Plan was initiated to restore the economic and social conditions ofthe people in Leyte to at least pre-typhoon levels, and to establish greater disaster resiliency. However, to simply re- establish pre-typhoon conditions would be a missed opportunity. The tragedy should be used to foster sustainable and climate-resilient agri-fisheries in the province of Leyte. The typhoon calamity demonstrated that the current practice ofmono-cropping (or monoculture) is unsustainable and not resilient to climate change. Agriculture systems that are small-scale and labor-intensive, with diverse crop strategies that consider on-farm, farm-related, and off-farm food and income generation should be developed. -

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

Official Rules for Georgia Saltwater Gamefish Record Submission

GEORGIA SALTWATER GAMEFISH RECORDS ANGLING RULES Angling rules associated with Georgia's Saltwater Gamefish Records Program are patterned largely after saltwater rules established by the International Game Fish Association. Subtle and obvious modifications, such as the lack of line classes in Georgia regulations, do exist. Each angler should carefully review each set of rules to discern these differences. Only fish landed in accordance with program rules outlined below and within the intent of these rules will be eligible for status as a Georgia Saltwater Gamefish Record. Like IGFA, the Georgia program is designed to recognize not only the fighting abilities of fishermen and their quarry, but also to promote ethical, sporting angling practices and a greater appreciation of coastal resources. In light of these considerations, each fisherman must determine whether his achievement reflects the intent and the spirit of these standards. Rules alone cannot ensure that angling experiences equal the catch, or vice versa. A. SAFETY Anglers must consider several factors in the pursuit of a Georgia Saltwater Gamefish Record. Primary among these is safety for the angler, crew, and/or vessel. Fishermen should carefully weigh safety demands against the inherent risks associated with certain gamefish, such as sharks, billfish, and other large species. It is ultimately the decision of the angler (and vessel captain, if applicable) to decide whether the catch can be safely accomplished under the existing circumstances and with the knowledge and equipment available. B. LINE 1. Monofilament, multifilalment, and lead core multifilament lines may be used. 2. Wire lines are prohibited. C. DOUBLE LINE AND LINE BACKING The use of a double line is not required. -

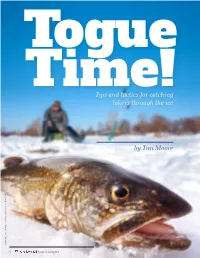

Tips and Tactics for Catching Lakers Through the Ice by Tim Moore

Togue Time!Tips and tactics for catching lakers through the ice by Tim Moore STOCKPHOTO.COM i © LEMONADE LUCY / FEDBUL - COMPOSITE IMAGE 4 January / February 2018 he crisp air, the frozen surface of a lake, the One day, while out with a group of ice anglers on Lake Tsilence broken only by the sound of ice augers Winnipesaukee, we began the trip jigging. The previous day, we had and snowmobiles, and the challenge of pursuing New done well jigging in this same Hampshire’s largest wild trout species. These are spot, and I felt confident that this day would be no different. A few some of the things that inspire ice anglers to get out lakers showed some interest early, onto New Hampshire’s frozen lakes each winter to but no takers. Then it was as if they had vanished. I was hesitant catch lake trout through the ice. to abandon such a consistent loca- tion, so I decided to try a couple Togue, laker, namaycush – whatever you call them, lake trout tip-ups with live smelt. Before I could get the second tip-up provide great fishing action through the ice during the long in the water, the flag went up on the first! I spent the next winter months in New Hampshire. few hours cycling between the two tip-ups. The action was As soon as the season opens and the ice is safe enough to non-stop. Later that afternoon, everything changed, and we fish, anglers from around New England flock to lakes such as were back to jigging. -

Protests Against His Rule

BUSINESS | 14 SPORT | 16 Jet Airways Gutsy Kerber approves rescue stays on deal to plug course for $1.2bn gap Doha final Friday 15 February 2019 | 10 Jumada II 1440 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 23 | Number 7803 | 2 Riyals Amir in Munich to Amir meets Ambassadors of Kyrgyzstan and Peru attend security conference QNA The 55th session of MUNICH/DOHA the Munich Security Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Conference is Hamad Al Thani arrived expected to be the yesterday evening in Munich, the biggest and most Federal Republic of Germany, to participate in the 55th session of important since the Munich Security Conference the founding of the (MSC) which will begin today and conference. will run until February 17. H H the Amir is accompanied by an official delegation. most important since the founding MSC is one of the largest and of the conference. Over the course most important international con- of three days, MSC 2019 will be ferences on the global security held under the chairmanship and defence policies. Twenty-one Wolfgang Ischinger and with the heads of state and 75 foreign and participation of German Chan- defence ministers participated in cellor Angela Merkel, US Vice- the last session of the MSC. President Mike Pence and a A strong strategic part- number of heads of governments nership, between Qatar and the and international community MSC, emerged during the 18th organisations. session of Doha Forum. The year This year’s conference will be 2011 witnessed the convening of held in exceptional circumstances the first meeting of MSC officials amidst many problems, crises and in Doha, where the two sides events, which will give the 2019 agreed to work together more session great importance. -

The Court of Justice Dismisses the Action Brought by the Netherlands Against the Ban on Fishing by Vessels Using Electric Pulse Trawls

Court of Justice of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 59/21 Luxembourg, 15 April 2021 Judgment in Case C-733/19 Press and Information Netherlands v Council and Parliament The Court of Justice dismisses the action brought by the Netherlands against the ban on fishing by vessels using electric pulse trawls The EU legislature has a wide discretion in this field and is not obliged to base its legislative choice on scientific and technical opinions only In 2019, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union adopted new rules on the conservation of fisheries resources and the protection of marine ecosystems. 1 Accordingly, certain destructive fishing gear or methods which use explosives, poison, stupefying substances, electric current, pneumatic hammers or other percussive instruments, towed devices and grabs for harvesting red coral or other types of coral and certain spear-guns are prohibited. However, the use of electric pulse trawl remains possible during a transitional period (until 30 June 2021) and under certain strict conditions. On 4 October 2019, the Netherlands brought an action before the Court of Justice for the annulment of the provisions of this regulation concerning electric pulse fishing vessels. The Netherlands argued inter alia that the EU legislature had not relied on the best scientific opinions available concerning the comparison of the environmental impacts of electric pulse trawling and traditional beam trawling in the exploitation of North Sea sole. In its judgment delivered today, the Court recalls, first of all, that the EU legislature is not obliged to base its legislative choice as to technical measures on the available scientific and technical opinions only. -

Fnw1834-4-Compressed.Pdf

Find us on Twitter £3.25 Join in the conversation 23 August 2018 Issue: 5426 @YourFishingNews £300M FLEET INVESTMENT TURN TO PAGE 2 FOR THE FULL REPORT Mary May – new Cygnus Typhoon 40 for Seahouses REGIONAL NEWS Seahouses skipper Neal Priestley’s new Cygnus … preparing to Valentine’s crew ‘on Typhoon 40 Mary May… start potting from Seahouses. guard’ for Folkestone Trawler Race 2018 Twenty-fiveboats and imaginatively-dressed crews took part in the popular Folkestone Trawler Race, held in fine sunny weather on 11-12 August. Further details on page 23. This year’s winners were: ● Valentine – first boat home, sponsored by Folkestone Trawlers ● Viking Princess – second boat home, sponsored by the Ship Inn ● Gilly – first motor boat home ● Poseidon – first visiting boat home ● Valentine – best-dressed fishing boat ● Viking Princess – best-dressed fishing boat crew ● Silver Lining – last boat home Seahouses skipper Neal Priestley, together with crewmen completion of a 900-mile delivery trip from Co Kerry. Darren Flanagan and Daniel Blackie, have started to fish static Insured by Sunderland Marine, Mary May is designed for gear on the new fast potter Mary May BK 8 off the coast of pot self-hauling and shooting. North Northumberland, reports David Linkie. Catches of lobsters and brown and velvet crab will be The battle-weary crew of the overall winner of Mary May is based on a Cygnus Typhoon 40 hull, moulded kept in optimum condition by an innovative sprinkler system Folkestone Trawler Race, Valentine, salute as they return and fully fitted out by Murphy Marine Services at Valentia fitted in a large hold amidships, before being landed daily to to harbour, ahead of Viking Princess in second place. -

Michigan Trout Unlimited “Position on Chumming”

Michigan Trout Unlimited “Position on Chumming” Background: Chumming has been practiced in Michigan to varying degrees by some anglers through the years, and at times, has been both lawful and prohibited. In recent years, the practice of chumming has been reported to be increasing, both in the number of people and in the volume of chum that is being used by each of them. It is a fishing practice that some anglers say works very well, while other anglers vigorously oppose the practice. Chumming involves luring or attracting fish by depositing chum -- fish eggs, corn, rice, noodles, maggots or oatmeal– into the water to get fish into a actively feed. It's often used to target rainbow (steelhead) trout with fish eggs. The prevalence of the chumming practice is causing conflicts due to its increasing in severity among some guides and recreational anglers and distribution on Michigan rivers. Left unaddressed, the problem will escalate and be significantly more difficult to manage later. MITU supports the Natural Resources Commission to ban chumming in Michigan. Current Issue: Michigan Trout Unlimited (MITU) is currently faced with deciding on a position on the practice of chumming. Very little “hard” data exists on the biological or sociological impacts of this practice, to help inform the Natural Resource Commission (NRC) with the decision-making process. This results in the impression that this is purely a “social” issue, where the NRC should simply evaluate the number in favor or opposed to chumming. This could not be further from the truth. Michigan Trout Unlimited “Position on Chumming” will therefore address the plausible risks and impacts that this practice could be assumed to pose, purpose the NRC use the “Precautionary Principle” to guide action, and confirm that approach bu presenting what other states have chosen to do on this issue.