3 Chromosome Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Familial Intellectual Disability As a Result of a Derivative Chromosome

Zhang et al. Molecular Cytogenetics (2018) 11:18 DOI 10.1186/s13039-017-0349-x RESEARCH Open Access Familial intellectual disability as a result of a derivative chromosome 22 originating from a balanced translocation (3;22) in a four generation family Kaihui Zhang1†, Yan Huang2†, Rui Dong1†, Yali Yang2, Ying Wang1, Haiyan Zhang1, Yufeng Zhang1, Zhongtao Gai1* and Yi Liu1* Abstract Background: Balanced reciprocal translocation is usually an exchange of two terminal segments from different chromosomes without phenotypic effect on the carrier while leading to increased risk of generating unbalanced gametes. Here we describe a four-generation family in Shandong province of China with at least three patients sharing severe intellectual disability and developmental delay resulting from a derivative chromosome 22 originating from a balanced translocation (3;22) involving chromosomes 3q28q29 and 22q13.3. Methods: The proband and his relatives were detected by using karyotyping, chromosome microarray analysis, fluorescent in situ hybridization and real-time qPCR. Results: The proband, a 17 month-old boy, presented with severe intellectual disability, developmental delay, specific facial features and special posture of hands. Pedigree analysis showed that there were at least three affected patients. The proband and other two living patients manifested similar phenotypes and were identified to have identically abnormal cytogenetic result with an unbalanced translocation of 9.0 Mb duplication at 3q28q29 and a 1.7Mb microdeletion at 22q13.3 by karyotyping and chromosome microarray analysis. His father and other five relatives had a balanced translocation of 3q and 22q. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and real-time qPCR definitely validated the results. -

Human Chromosome‐Specific Aneuploidy Is Influenced by DNA

Article Human chromosome-specific aneuploidy is influenced by DNA-dependent centromeric features Marie Dumont1,†, Riccardo Gamba1,†, Pierre Gestraud1,2,3, Sjoerd Klaasen4, Joseph T Worrall5, Sippe G De Vries6, Vincent Boudreau7, Catalina Salinas-Luypaert1, Paul S Maddox7, Susanne MA Lens6, Geert JPL Kops4 , Sarah E McClelland5, Karen H Miga8 & Daniele Fachinetti1,* Abstract Introduction Intrinsic genomic features of individual chromosomes can contri- Defects during cell division can lead to loss or gain of chromosomes bute to chromosome-specific aneuploidy. Centromeres are key in the daughter cells, a phenomenon called aneuploidy. This alters elements for the maintenance of chromosome segregation fidelity gene copy number and cell homeostasis, leading to genomic instabil- via a specialized chromatin marked by CENP-A wrapped by repeti- ity and pathological conditions including genetic diseases and various tive DNA. These long stretches of repetitive DNA vary in length types of cancers (Gordon et al, 2012; Santaguida & Amon, 2015). among human chromosomes. Using CENP-A genetic inactivation in While it is known that selection is a key process in maintaining aneu- human cells, we directly interrogate if differences in the centro- ploidy in cancer, a preceding mis-segregation event is required. It was mere length reflect the heterogeneity of centromeric DNA-depen- shown that chromosome-specific aneuploidy occurs under conditions dent features and whether this, in turn, affects the genesis of that compromise genome stability, such as treatments with micro- chromosome-specific aneuploidy. Using three distinct approaches, tubule poisons (Caria et al, 1996; Worrall et al, 2018), heterochro- we show that mis-segregation rates vary among different chromo- matin hypomethylation (Fauth & Scherthan, 1998), or following somes under conditions that compromise centromere function. -

Detailed Genetic and Physical Map of the 3P Chromosome Region Surrounding the Familial Renal Cell Carcinoma Chromosome Translocation, T(3;8)(Pl4.2;Q24.1)1

[CANCER RESEARCH 53. 3118-3124. July I. 1993] Detailed Genetic and Physical Map of the 3p Chromosome Region Surrounding the Familial Renal Cell Carcinoma Chromosome Translocation, t(3;8)(pl4.2;q24.1)1 Sal LaForgia,2 Jerzy Lasota, Parida Latif, Leslie Boghosian-Sell, Kumar Kastury, Masataka Olita, Teresa Druck, Lakshmi Atchison, Linda A. Cannizzaro, Gilad Barnea, Joseph Schlessinger, William Modi, Igor Kuzmin, Kaiman Tory, Berton Zbar, Carlo M. Croce, Michael Lerman, and Kay Huebner3 Jefferson Cancer Institute. Thomas Jefferson Medical College. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107 (S. L. J. L. L B-S.. K. K.. M. O.. T. D.. L A. C.. C. M. C.. K. H.I: Laboratory of Immunobiology. National Cancer Institute. Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center. Frederick. Maryland 21701 (F. L, l. K.. K. T.. B. Z.. M. L): Biological Carcinogenesis and Development Program. Program Resources Inc./Dyn Corp.. Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center. Frederick. Maryland 21701 1W. M.Õ: Chestnut Hill College. Philadelphia. Pennsylvania 19118 (L A.): and Department oj Pharmacology. New York University. New York. New York 10012 (G. B., J. S.I ABSTRACT location of the critical 3p region(s) harboring the target gene(s) had been hampered by the paucity of well-localized, widely available Extensive studies of loss of heterozygosity of 3p markers in renal cell molecular probes. Recently, efforts to isolate and localize large num carcinomas (RCCs) have established that there are at least three regions bers of 3p molecular probes have been undertaken (25-28). As the critical in kidney tumorigenesis, one most likely coincident with the von Hippel-Lindau gene at 3p25.3, one in 3p21 which may also be critical in probe density on 3p increased, in parallel with recent LOH studies, it small cell lung carcinomas, and one in 3pl3-pl4.2, a region which includes became clear that multiple independent loci on 3p were involved the 3p chromosome translocation break of familial RCC with the t(3;8)- (summarized in Refs. -

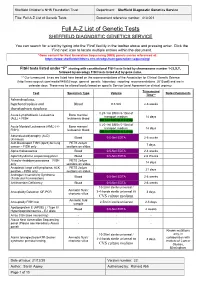

Full A-Z List of Genetic Tests Document Reference Number: 413.001

Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Department: Sheffield Diagnostic Genetics Service Title: Full A-Z List of Genetic Tests Document reference number: 413.001 Full A-Z List of Genetic Tests SHEFFIELD DIAGNOSTIC GENETICS SERVICE You can search for a test by typing into the ‘Find’ facility in the toolbar above and pressing enter. Click the ‘Find next’ icon to locate multiple entries within the document. *Gene content for Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) panels can be referenced at: https://www.sheffieldchildrens.nhs.uk/sdgs/next-generation-sequencing/ FISH tests listed under “F” starting with constitutional FISH tests listed by chromosome number 1-22,X,Y, followed by oncology FISH tests listed A-Z by gene name. ** Our turnaround times are listed here based on the recommendations of the Association for Clinical Genetic Science (http://www.acgs.uk.com/media/949852/acgs_general_genetic_laboratory_reporting_recommendations_2015.pdf) and are in calendar days. These may be altered locally based on specific Service Level Agreement or clinical urgency. Turnaround Test Specimen Type Volume Notes/Comments Time** Achondroplasia, hypchondroplasia and Blood 0.5-5ml 2-6 weeks thanatophoric dysplasia 0.25-1ml BM in 5-10ml of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Bone marrow/ transport medium 14 days (ALL) + FISH leukaemic blood OR 1ml BM/VB in Li Hep 0.25-1ml BM in 5-10ml of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) (+/- Bone marrow/ transport medium 14 days FISH) leukaemic blood OR 1ml BM/VB in Li Hep Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) Blood 0.5-5ml EDTA 2-6 weeks (X-linked) -

See Shalini C Reshmi's Curriculum Vitae

Shalini C. Reshmi, Ph.D. Contact Information: Institute for Genomic Medicine Nationwide Children’s Hospital 575 Childrens Crossroads, RB3-WB2233 Columbus, OH 43215 Lab: (614) 722-5321 Fax: (614) 355-6833 [email protected] CURRENT ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2/2018-present Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 7/2009-present Assistant Professor (Clinical), Department of Pathology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENT 10/2016-present Director, Clinical Laboratory Institute for Genomic Medicine Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH 9/2012-10/2016 Associate Director, Cytogenetics/Molecular Genetics Laboratory Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH 12/2008-9/2012 Assistant Director, Cytogenetics/Molecular Genetics Laboratory Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH EDUCATION 9/2001-5/2005 Ph.D. Human Genetics University of Pittsburgh, Graduate School of Public Health Pittsburgh, PA 9/1994-4/1996 M.S. Human Genetics University of Pittsburgh, Graduate School of Public Health Pittsburgh, PA 8/1988-5/1992 B.S. Biology The Catholic University of America Washington, D.C. TRAINING 7/2007-10/2008 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Clinical Molecular Genetics University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine Chicago, IL 7/2005-6/2007 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Clinical Cytogenetics University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine Chicago, IL Board Certifications 2 9/01/09- Diplomate, American Board of -

De Novo Centromere Formation on a Chromosome Fragment in Maize

De novo centromere formation on a chromosome fragment in maize Shulan Fua,1, Zhenling Lva,1, Zhi Gaob,1, Huajun Wuc, Junling Pangc, Bing Zhanga, Qianhua Donga, Xiang Guoa, Xiu-Jie Wangc, James A. Birchlerb,2, and Fangpu Hana,2 aState Key Laboratory of Plant Cell and Chromosome Engineering, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; bDivision of Biological Science, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211-7400; and cState Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Contributed by James A. Birchler, March 1, 2013 (sent for review February 3, 2013) The centromere is the part of the chromosome that organizes the been described for a barley chromosome (14) and a maize chro- kinetochore, which mediates chromosome movement during mito- mosome fragment in oat (15). Here we provide evidence that a sis and meiosis. A small fragment from chromosome 3, named small chromosome fragment in maize, which was recovered from Duplication 3a (Dp3a), was described from UV-irradiated materials UV irradiation decades ago, lacks CentC and CRM sequences but by Stadler and Roman in the 1940s [Stadler LJ, Roman H (1948) Ge- nevertheless has a de novo site with centromere function through- netics 33(3):273–303]. The genetic behavior of Dp3a is reminiscent of out the life cycle. This small chromosome fragment has a 350-kb a ring chromosome, but fluoresecent in situ hybridization detected CENH3-binding region, which is involved in new centromere for- telomeres at both ends, suggesting a linear structure. -

Cytogenetic Abnormalities in 772 ... -.: Scientific Press International Limited

Journal of Applied Medical Sciences, vol. 3, no. 3, 2014, 19-29 ISSN: 2241-2328 (print version), 2241-2336 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2014 Cytogenetic Abnormalities in 772 Patients with Mental Retardation (MR) in Southern Region of Turkey: Report and Review Osman Demirhan1*, Nilgün Tanrıverdi1, Erdal Tunç1, Dilara Süleymanova1 and Deniz Taştemir2 Abstract Mental retardation (MR) is a heterogeneous condition, affecting 1-3% of general population. Identification of chromosomal abnormalities (CAs) associated with mental disorders may be especially important given the unknown pathophysiology and the probable genetic heterogeneity of MR. In this study, we aimed to evaluate karyotype results of 772 MR cases, retrospectively. For karyotyping, standard lymphocyte culturing and GTG banding methods were done. For analysis, cytovision software was used. In result, out of 772 MR cases, 87 cases showed abnormal chromosomal constitutions (11.3%), and normal karyotype results were detected in 88.7% of all patients. Numerical and structural CAs were detected in 2.6% (20 of 772) and 8.7 (67 of 772) of cases, respectively. This study revealed Down syndrome as the most common chromosomal abnormality (1%). The ratio of X chromosome monosomy was 0.6%. In conclusion, patients with MR should be routinely karyotyped. Interesting CAs we found, may harbor important genes for MR and give important tips for linkage in possible genome scan projects. Keywords: Chromosomal abnormalities, GTG-banding, karyotype, MR 1 Introduction MR is the most frequent cause of serious handicap in children and young adults with an estimated prevalence up to 1-3% of the population, and is one of the more important topics in medical science [1,2]. -

Arabidopsis MZT1 Homologs GIP1 and GIP2 Are Essential for Centromere Architecture

Arabidopsis MZT1 homologs GIP1 and GIP2 are essential for centromere architecture Morgane Batzenschlagera, Inna Lermontovab, Veit Schubertb, Jörg Fuchsb, Alexandre Berra, Maria A. Koinic, Guy Houlnéa, Etienne Herzoga, Twan Ruttenb, Abdelmalek Aliouaa, Paul Franszc, Anne-Catherine Schmita, and Marie-Edith Chaboutéa,1 aInstitut de biologie moléculaire des plantes, CNRS, Université de Strasbourg, 67000 Strasbourg, France; bLeibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research OT Gatersleben, D-06466 Stadt Seeland, Germany; and cSwammerdam Institute for Life Sciences, University of Amsterdam, 1098 XH, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by James A. Birchler, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, and approved May 12, 2015 (received for review April 2, 2015) Centromeres play a pivotal role in maintaining genome integrity Previously, we characterized the γ-tubulin complex protein 3- by facilitating the recruitment of kinetochore and sister-chromatid interacting proteins (GIPs), GIP1 and GIP2 (Table S1), as es- cohesion proteins, both required for correct chromosome segre- sential for the recruitment of γ-tubulin complexes at microtubule gation. Centromeres are epigenetically specified by the presence (MT) organizing centers in Arabidopsis (7, 8). This function seems of the histone H3 variant (CENH3). In this study, we investigate the conserved in the human and Schizosaccharomyces pombe GIP role of the highly conserved γ-tubulin complex protein 3-interact- homologs named mitotic spindle organizing protein 1 (MZT1) ing proteins (GIPs) in Arabidopsis centromere regulation. We show (9–11). More recently, we localized GIPs at the nucleoplasm pe- that GIPs form a complex with CENH3 in cycling cells. GIP depletion riphery, close to chromocenters, where they modulate the nuclear in the gip1gip2 knockdown mutant leads to a decreased CENH3 architecture (12, 13). -

Deletion 2Q24

Deletion 2q24 Authors: Doctor Saskia M. Maas1 Scientific editor: Professor Raoul CM Hennekam Creation date: June 2001 Update: March 2004 1Department of Clinical Genetics, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 22700, 1100 DE Amsterdam. The Netherlands. mailto:S.M. [email protected] Abstract Key words Disease name and synonyms Excluded diseases Diagnosis criteria/definition Differential diagnosis Prevalence Clinical description Management including treatment Etiology Diagnostic methods Genetic counselling Antenatal diagnosis Unresolved questions References Abstract Deletion of 2q24, i.e. the loss of a small but specific region of the long arm of chromosome 2 forms a clinically recognizable syndrome. Twenty-three cases are known from the literature. Several symptoms are commonly seen in patients with chromosome aberrations, such as low birth weight, growth retardation, mental retardation, and low and malformed ears. However, the eye anomalies (coloboma, cataract and microphthalmia), anomalies of hands and feet (flexion deformities) and the congenital heart defects are more specific features, and are especially important in recognizing the clinical phenotype. Key words chromosome 2q23q24, interstitial deletion, camptodactyly, eye anomalies, cardiac defects Disease name and synonyms and feet and/or heart defects seem to be more Deletion of chromosome band 2q24 specific for this deletion. Monosomy 2q24 Differential diagnosis Excluded diseases If the cytogenetic anomaly is detected, no All the other chromosome anomalies associated differential diagnosis is needed. If no with low birth weight, growth retardation, mental microdeletion at 2q24 can be found the clinical retardation and facial dysmorphism. features may point to a vast array of other chromosome anomalies of monogenic entities. Diagnosis criteria/definition The diagnosis is made when chromosome Prevalence analysis shows a deletion of a specific part To our knowledge there are twenty-three (band q24) of the long arm of chromosome 2. -

Chromosome 17

Chromosome 17 Description Humans normally have 46 chromosomes in each cell, divided into 23 pairs. Two copies of chromosome 17, one copy inherited from each parent, form one of the pairs. Chromosome 17 spans about 83 million DNA building blocks (base pairs) and represents between 2.5 and 3 percent of the total DNA in cells. Identifying genes on each chromosome is an active area of genetic research. Because researchers use different approaches to predict the number of genes on each chromosome, the estimated number of genes varies. Chromosome 17 likely contains 1, 100 to 1,200 genes that provide instructions for making proteins. These proteins perform a variety of different roles in the body. Health Conditions Related to Chromosomal Changes The following chromosomal conditions are associated with changes in the structure or number of copies of chromosome 17. 17q12 deletion syndrome 17q12 deletion syndrome is a condition that results from the deletion of a small piece of chromosome 17 in each cell. Signs and symptoms of 17q12 deletion syndrome can include abnormalities of the kidneys and urinary system, a form of diabetes called maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 5 (MODY5), delayed development, intellectual disability, and behavioral or psychiatric disorders. Some females with this chromosomal change have Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, which is characterized by underdevelopment or absence of the vagina and uterus. Features associated with 17q12 deletion syndrome vary widely, even among affected members of the same family. Most people with 17q12 deletion syndrome are missing about 1.4 million DNA building blocks (base pairs), also written as 1.4 megabases (Mb), on the long (q) arm of the chromosome at a position designated q12. -

Mutagen Exposures and Chromosome 3 Aberrations in Acute Myelocytic Leukemia R Lindquist1, AM Forsblom1,ÅO¨ St2 and G Gahrton1

Leukemia (2000) 14, 112–118 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 0887-6924/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/leu Mutagen exposures and chromosome 3 aberrations in acute myelocytic leukemia R Lindquist1, AM Forsblom1,ÅO¨ st2 and G Gahrton1 1Department of Hematology, Karolinska Institutet at Huddinge University Hospital, Huddinge; and 2Department of Pathology and Cytology, Karolinska Institutet and Medilab, Stockholm, Sweden Thirteen patients with acute myelocytic leukemia (AML) and have had such exposures or other exposures of mutagens such with clonal aberrations involving chromosome 3 were studied. as previous therapies with antineoplastic agents and/or Three patients had monosomy 3, four had trisomy 3, and six had structural aberrations of chromosome 3. In the majority of radiation. cases chromosome 3 aberrations were parts of complex kary- otypes, but in two patients, the abnormalities appeared as sin- gle aberrations, one as an interstitial deletion del(3)(p13p21) Materials and methods and the other as monosomy 3. All breakpoints of chromosome 3 were found in the fragile site regions 3p14.2, 3q21 and 3q26– Patients 27. All patients with monosomy 3 or structural aberrations of chromosome 3 and one of the four patients with trisomy 3 had been exposed to mutagens, such as occupational exposures Thirteen patients with AML and chromosome 3 aberrations to organic solvents and/or petroleum products or treatments were investigated; six males and seven females. The median with irradiation or antineoplastic agents. The association age was 62 years (range 16–84) (Table 1). The patients partici- among mutagen exposure, structural chromosome 3 aber- pated in prospective treatment studies within the Leukemia rations and fragile sites in AML may indicate that targeting of Group of Middle Sweden (LGMS).19,20 Almost all patients with the mutagens to these sites is of importance for the etiology of the disease. -

Molecular Aspects of Y-Chromosome Degeneration in Drosophila

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 30, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Letter Sex chromosome evolution: Molecular aspects of Y-chromosome degeneration in Drosophila Doris Bachtrog Department of Ecology, Behavior and Evolution, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093, USA Ancient Y-chromosomes of various organisms contain few active genes and an abundance of repetitive DNA. The neo-Y chromosome of Drosophila miranda is in transition from an ordinary autosome to a genetically inert Y-chromosome, while its homolog, the neo-X chromosome, is evolving partial dosage compensation. Here, I compare four large genomic regions located on the neo-sex chromosomes that contain a total of 12 homologous genes. In addition, I investigate the partial coding sequence for 56 more homologous gene pairs from the neo-sex chromosomes. Little modification has occurred on the neo-X chromosome, and genes are highly constrained at the protein level. In contrast, a diverse array of molecular changes is contributing to the observed degeneration of the neo-Y chromosome. In particular, the four large regions surveyed on the neo-Y chromosome harbor several transposable element insertions, large deletions, and a large structural rearrangement. About one-third of all neo-Y-linked genes are nonfunctional, containing either premature stop codons and/or frameshift mutations. Intact genes on the neo-Y are accumulating amino acid and unpreferred codon changes. In addition, both 5Ј- and 3Ј-flanking regions of genes and intron sequences are less constrained on the neo-Y relative to the neo-X. Despite heterogeneity in levels of dosage compensation along the neo-X chromosomeofD.