Aneuploidy and More in Neural Diversity and Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Familial Intellectual Disability As a Result of a Derivative Chromosome

Zhang et al. Molecular Cytogenetics (2018) 11:18 DOI 10.1186/s13039-017-0349-x RESEARCH Open Access Familial intellectual disability as a result of a derivative chromosome 22 originating from a balanced translocation (3;22) in a four generation family Kaihui Zhang1†, Yan Huang2†, Rui Dong1†, Yali Yang2, Ying Wang1, Haiyan Zhang1, Yufeng Zhang1, Zhongtao Gai1* and Yi Liu1* Abstract Background: Balanced reciprocal translocation is usually an exchange of two terminal segments from different chromosomes without phenotypic effect on the carrier while leading to increased risk of generating unbalanced gametes. Here we describe a four-generation family in Shandong province of China with at least three patients sharing severe intellectual disability and developmental delay resulting from a derivative chromosome 22 originating from a balanced translocation (3;22) involving chromosomes 3q28q29 and 22q13.3. Methods: The proband and his relatives were detected by using karyotyping, chromosome microarray analysis, fluorescent in situ hybridization and real-time qPCR. Results: The proband, a 17 month-old boy, presented with severe intellectual disability, developmental delay, specific facial features and special posture of hands. Pedigree analysis showed that there were at least three affected patients. The proband and other two living patients manifested similar phenotypes and were identified to have identically abnormal cytogenetic result with an unbalanced translocation of 9.0 Mb duplication at 3q28q29 and a 1.7Mb microdeletion at 22q13.3 by karyotyping and chromosome microarray analysis. His father and other five relatives had a balanced translocation of 3q and 22q. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and real-time qPCR definitely validated the results. -

Whole Chromosome Gain Does Not in Itself Confer Cancer-Like Chromosomal Instability

Whole chromosome gain does not in itself confer cancer-like chromosomal instability Anders Valinda,1, Yuesheng Jina, Bo Baldetorpb, and David Gisselssona aDepartment of Clinical Genetics, Lund University, University and Regional Laboratories, Biomedical Center B13, Lund SE22184, Sweden; and bDepartment of Oncology, Lund University, Skåne University Hospital, Lund SE22185, Sweden Edited* by George Klein, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, and approved November 4, 2013 (received for review June 12, 2013) Constitutional aneuploidy is typically caused by a single-event and chromosomal instability in humans is using constitutional meiotic or early mitotic error. In contrast, somatic aneuploidy, aneuploidy syndromes as a model. Cells from patients with these found mainly in neoplastic tissue, is attributed to continuous syndromes provide a good experimental system for studying the chromosomal instability. More debated as a cause of aneuploidy effects of aneuploidy on overall genome stability on representative is aneuploidy itself; that is, whether aneuploidy per se causes human material. Such cells typically only have a single or a limited chromosomal instability, for example, in patients with inborn set of stem-line chromosome aberrations compared with tumor aneuploidy. We have addressed this issue by quantifying the level cell lines, which typically harbor a multitude of genetic lesions, as of somatic mosaicism, a proxy marker of chromosomal instability, well as a cancer phenotype. The few earlier studies performed on in patients with -

Post-Zygotic Mosaic Mutation in Normal Tissue from Breast Cancer Patient

Extended Abstract Research in Genes and Proteins Vol. 1, Iss. 1 2019 Post-zygotic Mosaic Mutation in Normal Tissue from Breast Cancer Patient Ryong Nam Kim Seoul National University Bio-MAX/NBIO, Seoul, Korea, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Even though numerous previous investigations had shed errors during replication, defects in chromosome fresh light on somatic driver mutations in cancer tissues, segregation during mitosis, and direct chemical attacks by the mutation-driven malignant transformation mechanism reactive oxygen species. the method of cellular genetic from normal to cancerous tissues remains still mysterious. diversification begins during embryonic development and during this study, we performed whole exome analysis of continues throughout life, resulting in the phenomenon of paired normal and cancer samples from 12 carcinoma somatic mosaicism. New information about the genetic patients so as to elucidate the post-zygotic mosaic diversity of cells composing the body makes us reconsider mutation which may predispose to breast carcinogenesis. the prevailing concepts of cancer etiology and We found a post-zygotic mosaic mutation PIK3CA pathogenesis. p.F1002C with 2% variant allele fraction (VAF) in normal tissue, whose respective VAF during a matched carcinoma Here, I suggest that a progressively deteriorating tissue, had increased by 20.6%. Such an expansion of the microenvironment (“soil”) generates the cancerous “seed” variant allele fraction within the matched cancer tissue and favors its development. Cancer Res; 78(6); 1375–8. ©2018 AACR. Just like nothing ha s contributed to the may implicate the mosaic mutation in association with the causation underlying the breast carcinogenesis. flourishing of physics quite war, nothing has stimulated the event of biology quite cancer. -

Genetic Mosaicism: What Gregor Mendel Didn't Know

Genetic mosaicism: what Gregor Mendel didn't know. R Hirschhorn J Clin Invest. 1995;95(2):443-444. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI117682. Research Article Find the latest version: https://jci.me/117682/pdf Genetic Mosaicism: What Gregor Mendel Didn't Know Editorial The word "mosaic" was originally used as an adjective to depending on the developmental stage at which the mutation describe any form of work or art produced by the joining to- occurs, may or may not be associated with somatic mosaicism gether of many tiny pieces that differ in size and color (1). In and may include all or only some of the germ cells. (A totally that sense, virtually all multicellular organisms are mosaics of different mechanism for somatic mosaicism has been recently cells of different form and function. Normal developmentally described, reversion of a transmitted mutation to normal [4]. determined mosaicism can involve permanent alterations of We have additionally identified such an event [our unpublished DNA in somatic cells such as the specialized cells of the im- observations]. ) mune system. In such specialized somatic cells, different re- Somatic and germ line mosaicism were initially inferred on arrangements of germ line DNA for immunoglobulin and T cell clinical grounds for a variety of diseases, including autosomal receptor genes and the different mutations accompanying these dominant and X-linked disorders, as presciently reviewed by rearrangements alter DNA and function. However, these alter- Hall (3). Somatic mosaicism for inherited disease was initially ations in individual cells cannot be transmitted to offspring definitively established for chromosomal disorders, such as since they occur only in differentiated somatic cells. -

Phenotype Manifestations of Polysomy X at Males

PHENOTYPE MANIFESTATIONS OF POLYSOMY X AT MALES Amra Ćatović* &Centre for Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sarajevo, Čekaluša , Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina * Corresponding author Abstract Klinefelter Syndrome is the most frequent form of male hypogonadism. It is an endocrine disorder based on sex chromosome aneuploidy. Infertility and gynaecomastia are the two most common symptoms that lead to diagnosis. Diagnosis of Klinefelter syndrome is made by karyotyping. Over years period (-) patients have been sent to “Center for Human Genetics” of Faculty of Medicine in Sarajevo from diff erent medical centres within Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with diagnosis suspecta Klinefelter syndrome, azoo- spermia, sterilitas primaria and hypogonadism for cytogenetic evaluation. Normal karyotype was found in (,) subjects, and karyotype was changed in (,) subjects. Polysomy X was found in (,) examinees. Polysomy X was expressed at the age of sexual maturity in the majority of the cases. Our results suggest that indication for chromosomal evaluation needs to be established at a very young age. KEY WORDS: polysomy X, hypogonadism, infertility Introduction Structural changes in gonosomes (X and Y) cause different distribution of genes, which may be exhibited in various phenotypes. Numerical aberrations of gonosomes have specific pattern of phenotype characteristics, which can be classified as clini- cal syndrome. Incidence of gonosome aberrations in males is / male newborn (). Klinefelter syndrome is the most common chromosomal disorder associated with male hypogonadism. According to different authors incidence is / male newborns (), /- (), and even / (). Very high incidence indicates that the zygotes with Klinefelter syndrome are more vital than those with other chromosomal aberrations. BOSNIAN JOURNAL OF BASIC MEDICAL SCIENCES 2008; 8 (3): 287-290 AMRA ĆATOVIĆ: PHENOTYPE MANIFESTATIONS OF POLYSOMY X AT MALES In , Klinefelter et al. -

3 Chromosome Chapter

Chromosome 3 ©Chromosome Disorder Outreach Inc. (CDO) Technical genetic content provided by Dr. Iosif Lurie, M.D. Ph.D Medical Geneticist and CDO Medical Consultant/Advisor. Ideogram courtesy of the University of Washington Department of Pathology: ©1994 David Adler.hum_03.gif Introduction The size of chromosome 3 is ~200 Mb. Within this chromosome, there are thousands of genes, many of which are necessary for normal intellectual development or involved in the formation of body organs. Deletions of Chromosome 3 The length of the short arm of chromosome 3 is ~90 Mb. Most known deletions of 3p are caused by the loss of its distal 15 Mb segment (3p25–pter). Deletions of the more proximal segments are relatively rare; there are only ~50 reports on such patients. Therefore, it would be premature to talk about any syndrome related to deletions of the proximal part of 3p. The location of the breakpoints, size of deletion, and reported abnormalities are different in most described patients. However, recurrent aortal stenosis in patients with deletion 3p11p14.2, abnormal lung lobation in patients with deletion 3p12p14.2, agenesis or hypoplasia of the corpus callosum in patients with deletion 3p13, microphthalmia and coloboma in patients with deletion 3p13p21.1, choanal atresia and absent gallbladder in patients with deletion 3p13p21, and hearing loss in patients with deletion 3p14 are all indicators that the above–mentioned segments likely contain genes involved in the formation of these systems. Deletions of 3p Deletion of 3p25–pter The most distal segment of the short arm of chromosome 3 is 3p26 and spans ~8 Mb. -

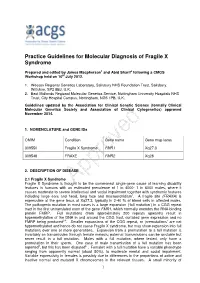

Practice Guidelines for Molecular Diagnosis of Fragile X Syndrome

Practice Guidelines for Molecular Diagnosis of Fragile X Syndrome Prepared and edited by James Macpherson 1 and Abid Sharif 2 following a CMGS Workshop held on 10 th July 2012. 1. Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory, Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, Salisbury, Wiltshire, SP2 8BJ, U.K. 2. East Midlands Regional Molecular Genetics Service, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, City Hospital Campus, Nottingham, NG5 1PB, U.K. Guidelines updated by the Association for Clinical Genetic Science (formally Clinical Molecular Genetics Society and Association of Clinical Cytogenetics) approved November 2014. 1. NOMENCLATURE and GENE IDs OMIM Condition Gene name Gene map locus 309550 Fragile X Syndrome FMR1 Xq27.3 309548 FRAXE FMR2 Xq28 2. DESCRIPTION OF DISEASE 2.1 Fragile X Syndrome Fragile X Syndrome is thought to be the commonest single-gene cause of learning disability features in humans with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 4000- 1 in 6000 males, where it causes moderate to severe intellectual and social impairment together with syndromic features including large ears and head, long face and macroorchidism 1. A fragile site (FRAXA) is expressible at the gene locus at Xq27.3, typically in 2-40 % of blood cells in affected males. The pathogenic mutation in most cases is a large expansion (‘full mutation’) in a CGG repeat tract in the first untranslated exon of the gene FMR1, which normally encodes the RNA-binding protein FMRP. Full mutations (from approximately 200 repeats upwards) result in hypermethylation of the DNA in and around the CGG tract, curtailed gene expression and no FMRP being produced 2-4. Smaller expansions of the CGG repeat, or ‘premutations’ are not hypermethylated and hence do not cause Fragile X syndrome, but may show expansion into full mutations over one or more generations. -

An Unusual Case of Mosaic Down's Syndrome Involving Two Different

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.26.3.198 on 1 March 1989. Downloaded from 198 Case reports An unusual case of mosaic Down's syndrome involving two different Robertsonian translocations M J CLARKE*, D A G THOMSON*, M J GRIFFITHS*, J G BISSENDENt, A AUKETTt, AND J L WATT* From *the Regional Cytogenetics Unit, Birmingham Maternity Hospital, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TG; and tDudley Road Hospital, Dudley Road, Birmingham B18 7QH. SUMMARY A baby girl with some of the Case report stigmata of Down's syndrome was found to be a mosaic with three different cell lines: The patient was born at term in February 1987 45,XX,-13,-21,+t(13q21q)/(46,XX/46,XX, weighing 2800 g after a normal pregnancy and The rearrange- delivery. The mother was 27 years old and the father -21, +t(2lq21q). chromosome 29. This was their first child and neither parent has ments detected in this patient appear to have any family history of Down's syndrome. arisen de novo. In the normal cell line the Some features of Down's syndrome were noted in terminal end of the p arm of one chromosome the infant soon after birth and she was referred for 21 is thought to have been damaged. It seems cytogenetic analysis. Physical examination showed a probable that this is related to the other typical mongoloid slant to the eyes, low set ears, a chromosomal anomalies found. single palmar crease, broad hands with stubby fingers, a large space between her big toe and the rest of her toes, and a slightly protuberant tongue. -

Cytogenetics, Chromosomal Genetics

Cytogenetics Chromosomal Genetics Sophie Dahoun Service de Génétique Médicale, HUG Geneva, Switzerland [email protected] Training Course in Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Geneva 2010 Cytogenetics is the branch of genetics that correlates the structure, number, and behaviour of chromosomes with heredity and diseases Conventional cytogenetics Molecular cytogenetics Molecular Biology I. Karyotype Definition Chromosomal Banding Resolution limits Nomenclature The metaphasic chromosome telomeres p arm q arm G-banded Human Karyotype Tjio & Levan 1956 Karyotype: The characterization of the chromosomal complement of an individual's cell, including number, form, and size of the chromosomes. A photomicrograph of chromosomes arranged according to a standard classification. A chromosome banding pattern is comprised of alternating light and dark stripes, or bands, that appear along its length after being stained with a dye. A unique banding pattern is used to identify each chromosome Chromosome banding techniques and staining Giemsa has become the most commonly used stain in cytogenetic analysis. Most G-banding techniques require pretreating the chromosomes with a proteolytic enzyme such as trypsin. G- banding preferentially stains the regions of DNA that are rich in adenine and thymine. R-banding involves pretreating cells with a hot salt solution that denatures DNA that is rich in adenine and thymine. The chromosomes are then stained with Giemsa. C-banding stains areas of heterochromatin, which are tightly packed and contain -

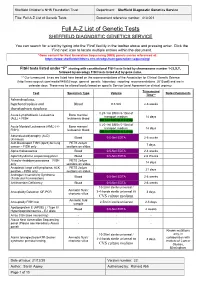

Full A-Z List of Genetic Tests Document Reference Number: 413.001

Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Department: Sheffield Diagnostic Genetics Service Title: Full A-Z List of Genetic Tests Document reference number: 413.001 Full A-Z List of Genetic Tests SHEFFIELD DIAGNOSTIC GENETICS SERVICE You can search for a test by typing into the ‘Find’ facility in the toolbar above and pressing enter. Click the ‘Find next’ icon to locate multiple entries within the document. *Gene content for Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) panels can be referenced at: https://www.sheffieldchildrens.nhs.uk/sdgs/next-generation-sequencing/ FISH tests listed under “F” starting with constitutional FISH tests listed by chromosome number 1-22,X,Y, followed by oncology FISH tests listed A-Z by gene name. ** Our turnaround times are listed here based on the recommendations of the Association for Clinical Genetic Science (http://www.acgs.uk.com/media/949852/acgs_general_genetic_laboratory_reporting_recommendations_2015.pdf) and are in calendar days. These may be altered locally based on specific Service Level Agreement or clinical urgency. Turnaround Test Specimen Type Volume Notes/Comments Time** Achondroplasia, hypchondroplasia and Blood 0.5-5ml 2-6 weeks thanatophoric dysplasia 0.25-1ml BM in 5-10ml of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Bone marrow/ transport medium 14 days (ALL) + FISH leukaemic blood OR 1ml BM/VB in Li Hep 0.25-1ml BM in 5-10ml of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) (+/- Bone marrow/ transport medium 14 days FISH) leukaemic blood OR 1ml BM/VB in Li Hep Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) Blood 0.5-5ml EDTA 2-6 weeks (X-linked) -

Special Report

RARERARE PEDIATRICPEDIATRIC DISEASESDISEASES SPECIAL REPORT SELECTED ARTICLES Rare Diseases Pose a Pressing Challenge: Are State-by-State Differences in Newborn 02 09 Get the Diagnostic Work Done Swiftly Screening an Impediment or Asset? Rare Epileptic Encephalopathies: Neurodevelopmental Concerns May Emerge 05 21 Update on Directions in Treatment Later in Zika-exposed Infants EDITOR’S NOTE housands of rare diseases have been identified, but only T 35 core conditions are on the federal Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). But the majority of states don’t screen for all 35 conditions. Read on to learn about the pros and cons of state-by- state differences in newborn screening for rare disorders. But newborn Catherine Cooper screening is not the only way to learn about a child’s rare disease. There Nellist is genetic screening, and now it is more widely available than ever. But how to make sense of that information? Certified genetic counselors will help, but health care providers need education about what to do when a rare disease is diagnosed. In this Rare Pediatric Diseases Special Report, there are resources for you as health care providers and for your patients provided by the National Institutes of Health and by the National Organization for Rare Disorders. Explore a synopsis of existing and emerging treatments of three rare epileptic encephalopathies that occur in infancy and early childhood— West syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome. Learn about important advancements in the treatment of three rare pediatric neuromuscular disorders—spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), and X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM)—and how improved quality of life and survival will challenge current EDITOR systems of transition care. -

Double Aneuploidy in Down Syndrome

Chapter 6 Double Aneuploidy in Down Syndrome Fatma Soylemez Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/60438 Abstract Aneuploidy is the second most important category of chromosome mutations relat‐ ing to abnormal chromosome number. It generally arises by nondisjunction at ei‐ ther the first or second meiotic division. However, the existence of two chromosomal abnormalities involving both autosomal and sex chromosomes in the same individual is relatively a rare phenomenon. The underlying mechanism in‐ volved in the formation of double aneuploidy is not well understood. Parental ori‐ gin is studied only in a small number of cases and both nondisjunctions occurring in a single parent is an extremely rare event. This chapter reviews the characteristics of double aneuploidies in Down syndrome have been discussed in the light of the published reports. Keywords: Double aneuploidy, Down Syndrome, Klinefelter Syndrome, Chromo‐ some abnormalities 1. Introduction With the discovery in 1956 that the correct chromosome number in humans is 46, the new area of clinical cytogenetic began its rapid growth. Several major chromosomal syndromes with altered numbers of chromosomes were reported, such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Turner syndrome (45,X) and Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY). Since then it has been well established that chromosome abnormalities contribute significantly to genetic disease resulting in reproductive loss, infertility, stillbirths, congenital anomalies, abnormal sexual development, mental retardation and pathogenesis of malignancy [1]. Clinical features of patients with common autosomal or sex chromosome aneuploidy is shown in Table 1. © 2015 The Author(s). Licensee InTech. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.