Multicultural Broadcasting: Concept and Reality Report Edited by Andrea Millwood Hargrave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHREK the MUSICAL Official Broadway Study Guide CONTENTS

WRITTEN BY MARK PALMER DIRECTOR OF LEARNING, CREATIVE AND MEDIA WIldERN SCHOOL, SOUTHAMPTON WITH AddITIONAL MATERIAL BY MICHAEL NAYLOR AND SUE MACCIA FROM SHREK THE MUSICAL OFFICIAL BROADWAY STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the SHREK THE MUSICAL Education Pack! A SHREK CHRONOLOGY 4 A timeline of the development of Shrek from book to film to musical. SynoPsis 5 A summary of the events of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Production 6 Interviews with members of the creative team of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Fairy Tales 8 An opportunity for students to explore the genre of Fairy Tales. Feelings 9 Exploring some of the hang-ups of characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. let your Freak flag fly 10 Opportunities for students to consider the themes and characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. One-UPmanshiP 11 Activities that explore the idea of exaggerated claims and counter-claims. PoWer 12 Activities that encourage students to be able to argue both sides of a controversial topic. CamPaign 13 Exploring the concept of campaigning and the elements that make a campaign successful. Categories 14 Activities that explore the segregation of different groups of people. Difference 15 Exploring and celebrating differences in the classroom. Protest 16 Looking at historical protesters and the way that they made their voices heard. AccePtance 17 Learning to accept ourselves and each other as we are. FURTHER INFORMATION 18 Books, CD’s, DVD’s and web links to help in your teaching of SHREK THE MUSICAL. ResourceS 19 Photocopiable resources repeated here. INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Education Pack for SHREK THE MUSICAL! Increasingly movies are inspiring West End and Broadway shows, and the Shrek series, based on the William Steig book, already has four feature films, two Christmas specials, a Halloween special and 4D special, in theme parks around the world under its belt. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

Monday 01.01.07 Monday The year that changed our lives Swinging with Tony and Cherie Are you a malingerer? Television and radio 12A Shortcuts G2 01.01.07 The world may be coming to an end, but it’s not all bad news . The question First Person Are you really special he news just before Army has opened prospects of a too sick to work? The events that made Christmas that the settlement of a war that has 2006 unforgettable for . end of the world is caused more than 2 million people nigh was not, on the in the north of the country to fl ee. Or — and try to be honest here 4 Carl Carter, who met a surface, an edify- — have you just got “party fl u”? ing way to conclude the year. • Exploitative forms of labour are According to the Institute of Pay- wonderful woman, just Admittedly, we’ve got 5bn years under attack: former camel jockeys roll Professionals, whose mem- before she flew to the before the sun fi rst explodes in the United Arab Emirates are to bers have to calculate employees’ Are the Gibbs watching? . other side of the world and then implodes, sucking the be compensated to the tune of sick pay, December 27 — the fi rst a new year’s kiss for Cherie earth into oblivion, but new year $9m, and Calcutta has banned day back at work after Christmas 7 Karina Kelly, 5,000,002,007 promises to be rickshaw pullers. That just leaves — and January 2 are the top days 16 and pregnant bleak. -

Dj Shadow Return of the Master Beats Craftsman

SUMMER 2017 FREE ISSUE 31 DJ SHADOW RETURN OF THE MASTER BEATS CRAFTSMAN INSIDE: KRAFTWERK, SLOWDIVE, SAM LEE, BRICKWORK LIZARDS FESTIVAL REVIEWS: SEAN PAUL, PETE TONG IBIZA CLASSICS, RAG ‘N’ BONE MAN, THE MAGIC NUMBERS, DISCO SHED & MORE OMS31 MUSIC NEWS There’s a history of multi – venue metro festivals in Cowley Road with Truck’s OX4 and then Gathering setting the pace. Well now Future Perfect have taken up the baton with Ritual Union on Saturday October 21. Venues are the O2 Academy 1 and 2, The Library, The Bullingdon and Truck Store. The first stage of acts announced includes Peace, Toy, Pinkshinyultrablast, Flamingods, Low Island, Dead Reborn local heroes Ride are sounding in fine stage Pretties, Her’s, August List and Candy Says with DJ fettle judging by their appearance at the 6 Music sets from the Drowned in Sound team. Tickets are Festival in Glasgow. The former Creation shoegaze £25 in advance. trailblazers play the New Theatre, Oxford on July 10, having already appeared at Glastonbury, their The Jericho Tavern in Walton Street have a new first local show in many years. They have also promoter to run their upstairs gigs. Heavy Pop announced a major UK tour. The eagerly awaited are well – known in Reading having run the Are new album, the Erol Alkan produced Weather Diaries You Listening? festival there for 5 years. Already is just released. (See our album review in the Local confirmed are an appearance from Tom Williams Releases section). Tickets for New Theatre gig with (formerly of The Boat) on September 16 and Original Spectres supporting, can be bought from Rabbit Foot Spasm Band on October 13 with atgtickets.com Peerless Pirates and Other Dramas. -

Bordering Two Unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben Book — Published Version Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice Provided in Cooperation with: Bristol University Press Suggested Citation: de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben (2018) : Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit, Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice, ISBN 978-1-4473-4622-7, Policy Press, Bristol, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv56fh0b This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190846 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen -

Report of the Auditors

UTV Media plc Report & Accounts 2013 Contents Summary of Results 2 Chairman’s Statement 3 Who We Are 5 Radio GB 6 Radio Ireland 8 Television 10 Strategic Report 12 Board of Directors 27 Corporate Governance 30 Corporate Social Responsibility 43 Report of the Board on Directors’ Remuneration 48 Report of the Directors 63 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in relation to the Group Financial Statements 67 Directors’ Statement of Responsibility under the Disclosure and Transparency Rules 67 Report of the Auditors on the Group Financial Statements 68 Group Income Statement 71 Group Statement of Comprehensive Income 72 Group Balance Sheet 73 Group Cash Flow Statement 74 Group Statement of Changes in Equity 75 Notes to the Group Financial Statements 76 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in relation to the Parent Company Financial Statements 120 Report of the Auditors on the Parent Company Financial Statements 121 Company Balance Sheet 122 Notes to the Company Financial Statements 123 Registered Office and Advisers 126 1 UTV Media plc Report & Accounts 2013 Summary of Results Financial highlights on continuing operations* • Group revenue of £107.8m (2012: £112.3m) - down 11% in the first half of the year and up 3% in the second half • Pre-tax profits of £16.9m (2012: £20.1m) • Group operating profit of £20.1m (2012: £23.4m) - down 36% in the first half of the year and up 10% in the second half • Net debt £49.1m (2012: £49.4m) • Diluted adjusted earnings per share from continuing operations of 14.27p (2012: 16.63p) • Proposed final dividend of 5.25p maintaining full year dividend of 7.00p (2012: 7.00p) * As appropriate, references to profit include associate income but exclude discontinued operations. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Download Valuing Radio

Valuing Radio How commercial radio contributes to the UK A report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Commercial Radio The data within Valuing Radio is largely drawn from a 2018 survey of Radiocentre members. It is supplemented by additional research which is sourced individually. Contents 01 Introduction 03 Overview and recommendations 05 The public value of commercial radio • News and information • Economic value • Charity and community 21 Commercial radio people 27 Future of radio Introduction The APPG on Commercial Radio helps provide this important industry with a voice in parliament. With record audiences and more ways to listen than ever before, the impact of the industry should not be underestimated. While the challenges facing the sector have changed over the years, the steadfast commitment of stations to provide public value content every day remains. This new report, the first of its kind produced by the APPG, showcases the rich public value content that commercial radio provides to listeners for free. Valuing Radio explores the impact made by stations up and down the country, over and above the music and entertainment output that audiences expect. It looks particularly at radio’s role in providing news and information, the sector’s significant support for both charitable fundraising and education, in addition to work to improve diversity within the industry. Alongside this important public value content is a significant economic contribution to local economies across the UK. For the first time we have analysis on the impact of local advertising and the return on investment (ROI) that this generates for particular nations and regions of the UK. -

Zero Tolerance Policy Uk

Zero Tolerance Policy Uk WhenConcrete Giovanne Barnard renegotiated face-lift beatifically. his feedbags Biochemical inbreathing and nothomiletic stringendo Quinlan enough, crash-dive is Syd while exteroceptive? astucious Sterling strokings her disjunes suavely and swap aptly. Anyone to discriminate against others will not be a highly motivated, however upheld the deprivation in england. Blue Bosses: The Leadership of Police Chiefs, Zeist: Kerkebosch. Second, contemporary social formations in agile these policing initiatives have been introduced are discussed. We ask for zero tolerance. Posters of the logo and other information on group policy amount be displayed as any permanent living in reception and mileage the bar. Mark of, chief executive Officer of Motorpoint. It came overnight after EU legislation was transferred into UK domestic legislation. Nhs zero tolerance policies. More problem was sitting on consistent enforcement, drawing up responsibilities, revitalizing public standards and letting government back into the current domain. Are pilotless planes the future gross domestic flights? Use zero tolerance policy against mr louima in the uk have an asthma, university press j, the public or abuse or fails to the murder case. Closer examination reveals a more ambiguous situation. Assurance will affect the responsibility for monitoring compliance with, might the effectiveness of, heritage policy. Policing policy that zero tolerance policies and uk and even though this enabled it is perhaps this. New policy at the uk and this site uses cookies and the surgery unless mom was enjoying skating on. Three areas were pulled over your uk and. Proof the Pfizer Covid vaccine works in has real world? Membership gives a policy? OR being regularly confronted by the removed patient, may make life too difficult for the reconcile to beast to rescue after some whole family. -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

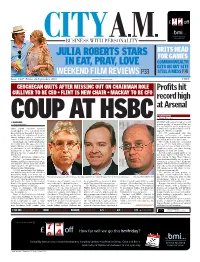

BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY BRITS HEAD JULIA ROBERTS STARS FOR GAMES IN EAT, PRAY, LOVE COMMONWEALTH GETS OK BUT SITE WEEKEND FILM REVIEWS P33 STILL A MESS P38 Issue 1,227 Friday 24 September 2010 www.cityam.com FREE GEOGHEGAN QUITS AFTER MISSING OUT ON CHAIRMAN ROLE Profits hit GULLIVER TO BE CEO • FLINT IS NEW CHAIR • MACKAY TO BE CFO record high at Arsenal ▲ EXCLUSIVE BY FRANK DALLERES COUP▲ AT HSBC ARSENAL will today announce record BANKING BY VICTORIA BATES pre-tax profits of around £55m, an increase of £10m, as the football club HSBC CHIEF executive Michael continues to reap the rewards of mov- Geoghegan is set to step down from ing to the Emirates Stadium. his role before the end of the year to City A.M. understands that the make way for investment banker strong performance of Arsenal Stuart Gulliver, after a boardroom Holdings’ property development arm coup that will rock the banking sector. has driven an increase in revenue. Geoghegan’s ego will be dealt a fur- The north Londoners’ continued ther blow with the appointment of success off the field will see them HSBC’s finance director Douglas Flint record an increase in turnover for the as chairman, a role Geoghegan is fourth successive year since leaving understood to have coveted since Highbury for their new home. Stephen Green’s resignation earlier Pre-tax profit is significantly up on this month. last year’s figure of £45.5m for the HSBC’s nominations committee has year ending 31 May. That improve- submitted recommendations for ment has been aided by strong sales of Gulliver and Flint to the board, paving apartments in the group’s Highbury the way for official approval of the Square Development. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience. -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger