Segmental Variation in the Activity and Function of the Equine Longissimus Dorsi Muscle During Walk and Trot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Structure and Function of Breathing

CHAPTERCONTENTS The structure-function continuum 1 Multiple Influences: biomechanical, biochemical and psychological 1 The structure and Homeostasis and heterostasis 2 OBJECTIVE AND METHODS 4 function of breathing NORMAL BREATHING 5 Respiratory benefits 5 Leon Chaitow The upper airway 5 Dinah Bradley Thenose 5 The oropharynx 13 The larynx 13 Pathological states affecting the airways 13 Normal posture and other structural THE STRUCTURE-FUNCTION considerations 14 Further structural considerations 15 CONTINUUM Kapandji's model 16 Nowhere in the body is the axiom of structure Structural features of breathing 16 governing function more apparent than in its Lung volumes and capacities 19 relation to respiration. This is also a region in Fascla and resplrstory function 20 which prolonged modifications of function - Thoracic spine and ribs 21 Discs 22 such as the inappropriate breathing pattern dis- Structural features of the ribs 22 played during hyperventilation - inevitably intercostal musculature 23 induce structural changes, for example involving Structural features of the sternum 23 Posterior thorax 23 accessory breathing muscles as well as the tho- Palpation landmarks 23 racic articulations. Ultimately, the self-perpetuat- NEURAL REGULATION OF BREATHING 24 ing cycle of functional change creating structural Chemical control of breathing 25 modification leading to reinforced dysfunctional Voluntary control of breathing 25 tendencies can become complete, from The autonomic nervous system 26 whichever direction dysfunction arrives, for Sympathetic division 27 Parasympathetic division 27 example: structural adaptations can prevent NANC system 28 normal breathing function, and abnormal breath- THE MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION 30 ing function ensures continued structural adap- Additional soft tissue influences and tational stresses leading to decompensation. -

Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Anatomy

ThoracicThoracic andand LumbarLumbar SpineSpine AnatomyAnatomy www.fisiokinesiterapia.biz ThoracicThoracic VertebraeVertebrae Bodies Pedicles Laminae Spinous Processes Transverse Processes Inferior & Superior Facets Distinguishing Feature – Costal Fovea T1 T2-T8 T9-12 ThoracicThoracic VertebraeVertebrae andand RibRib JunctionJunction FunctionsFunctions ofof ThoracicThoracic SpineSpine – Costovertebral Joint – Costotransverse Joint MotionsMotions – All available – Flexion and extension limited – T7-T12 LumbarLumbar SpineSpine BodiesBodies PediclesPedicles LaminaeLaminae TransverseTransverse ProcessProcess SpinousSpinous ProcessProcess ArticularArticular FacetsFacets LumbarLumbar SpineSpine ThoracolumbarThoracolumbar FasciaFascia LumbarLumbar SpineSpine IliolumbarIliolumbar LigamentsLigaments FunctionsFunctions ofof LumbarLumbar SpineSpine – Resistance of anterior translation – Resisting Rotation – Weight Support – Motion IntervertebralIntervertebral DisksDisks RatioRatio betweenbetween diskdisk thicknessthickness andand vertebralvertebral bodybody heightheight DiskDisk CompositionComposition – Nucleus pulposis – Annulus Fibrosis SpinalSpinal LigamentsLigaments AnteriorAnterior LongitudinalLongitudinal PosteriorPosterior LongitudinalLongitudinal LigamentumLigamentum FlavumFlavum InterspinousInterspinous LigamentsLigaments SupraspinousSupraspinous LigamentsLigaments IntertransverseIntertransverse LigamentsLigaments SpinalSpinal CurvesCurves PosteriorPosterior ViewView SagittalSagittal ViewView – Primary – Secondary -

Trunk Control During Gait: Walking with Wide and Narrow Step Widths Present Distinct 4 Challenges 5 6 Hai-Jung Steffi Shih, James Gordon, Kornelia Kulig

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.30.274423; this version posted November 17, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Original Article 2 3 Trunk Control during Gait: Walking with Wide and Narrow Step Widths Present Distinct 4 Challenges 5 6 Hai-Jung Steffi Shih, James Gordon, Kornelia Kulig 7 Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 8 CA, USA 9 10 11 Corresponding Author: 12 Hai-Jung Steffi Shih 13 Address: 1540 E. Alcazar St, CHP 155, Los Angeles, CA, 90033 14 Telephone: +1 (323)442-2089 15 Fax: +1 (323)442-1515 16 Email: [email protected] 17 18 19 Keywords: Gait stability, Lateral stability, Trunk coordination, Muscle activation, Foot placement 20 Word count (intro-discussion): 3519 21 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.30.274423; this version posted November 17, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 22 Abstract 23 The active control of the trunk plays an important role in frontal plane gait stability. We 24 characterized trunk control in response to different step widths using a novel feedback system 25 and examined the different effects of wide and narrow step widths as they each present unique 26 task demands. -

Meat Quality Workshop: Know Your Muscle, Know Your Meat BEEF

2/6/2017 Meat Quality Workshop: Know Your Muscle, Know Your Meat Principles of Muscle Profiling, Aging, and Nutrition Dale R. Woerner, Ph.D., Colorado State University BEEF- Determining Value 1 2/6/2017 Slight00 Small00 Modest00 Moderate00 SLAB00 MAB00 ACE ABC Maturity Group Approximate Age A 9‐30 months B 30‐42 months C 42‐72 months D E 72‐96 months 96 months or older Augmentation of USDA Grade Application 2 2/6/2017 Effect of Marbling Degree on Probability of a Positive Sensory Experience Probability of a Positive Sensory Experience 0.99a 0.98a 1 0.88b 0.9 0.82b 0.8 0.7 0.62c 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.29d 0.3 0.2 0.15e 0.1 0 TR SL SM MT MD SA MA Colorado State University M.S. Thesis: M. R. Emerson (2011) 3 2/6/2017 Carcass Weight Trend 900 All Fed Cattle CAB® 875 850 +55 lbs. in 5 years 825 +11 lbs. / year 800 775 750 +117 lbs. in 20 years Hot Carcass (lbs.) Weight +5.8 lbs. / year 725 Year 4 2/6/2017 Further Problems • Food service portion cutting problems = 8 oz. • Steak preparation problems = 8 oz. A 1,300‐pound, Yield Grade 3 steer yields 639 pounds of retail cuts from an 806‐pound carcass. Of the retail cuts, 62% are roasts and steaks (396 pounds) and 38% are ground beef and stew meat (243 pounds). 5 2/6/2017 Objective of Innovative Fabrication • Use quality-based break points during fabrication • Add value to beef by optimizing use of high-quality cuts • Add value to beef cuts by improving leanness and portion size $2.25 $7.56 $2.75 $4.66 $2.50 $12.73 $2.31 $2.85 $3.57 $1.99 Aging Response Premium USDA Choice USDA Select Muscle Aging response -

Muscles of Mastication Muscles That Move the Head

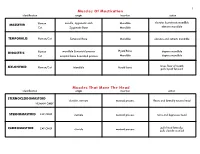

1 Muscles Of Mastication identification origin insertion action maxilla, zygomatic arch Mandible elevates & protracts mandible MASSETER Human Cat Zygomatic Bone Mandible elevates mandible TEMPORALIS Human/Cat Temporal Bone Mandible elevates and retracts mandible Hyoid Bone DIGASTRIC Human mandible & mastoid process depress mandible Cat occipital bone & mastoid process Mandible depress mandible raises floor of mouth; MYLOHYOID Human/Cat Mandible Hyoid bone pulls hyoid forward Muscles That Move The Head identification origin insertion action STERNOCLEIDOMAStoID clavicle, sternum mastoid process flexes and laterally rotates head HUMAN ONLY STERNOMAStoID CAT ONLY sternum mastoid process turns and depresses head pulls head laterally; CLEIDOMAStoID CAT ONLY clavicle mastoid process pulls clavicle craniad 2 Muscles Of The Hyoid, Larynx And Tongue identification origin insertion action Human Sternum Hyoid depresses hyoid bone STERNOHYOID Cat costal cartilage 1st rib Hyoid pulls hyoid caudally; raises ribs and sternum sternum Throid cartilage of larynx Human depresses thyroid cartilage STERNothYROID Cat costal cartilage 1st rib Throid cartilage of larynx pulls larynx caudad elevates thyroid cartilage and Human thyroid cartilage of larynx Hyoid THYROHYOID depresses hyoid bone Cat thyroid cartilage of larynx Hyoid raises larynx GENIOHYOID Human/Cat Mandible Hyoid pulls hyoid craniad 3 Muscles That Attach Pectoral Appendages To Vertebral Column identification origin insertion action Human Occipital bone; Thoracic and Cervical raises clavicle; adducts, -

The Anatomy and Function of the Equine Thoracolumbar Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

Aus dem Veterinärwissenschaftlichen Department der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Lehrstuhl für Anatomie, Histologie und Embryologie Vorstand: Prof. Dr. Dr. Fred Sinowatz Arbeit angefertigt unter der Leitung von Dr. Renate Weller, PhD, MRCVS The Anatomy and Function of the equine thoracolumbar Longissimus dorsi muscle Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der tiermedizinischen Doktorwürde der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Vorgelegt von Christina Carla Annette von Scheven aus Düsseldorf München 2010 2 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Joachim Braun Berichterstatter: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Johann Maierl Korreferentin: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Bettina Wollanke Tag der Promotion: 24. Juli 2010 3 Für meine Familie 4 Table of Contents I. Introduction................................................................................................................ 8 II. Literature review...................................................................................................... 10 II.1 Macroscopic anatomy ............................................................................................. 10 II.1.1 Comparative evolution of the body axis ............................................................ 10 II.1.2 Axis of the equine body ..................................................................................... 12 II.1.2.1 Vertebral column of the horse.................................................................... -

Adapted Sport Effect on Postural Control After Spinal Cord Injury

Spinal Cord (2016) 54, 1188–1196 & 2016 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/16 www.nature.com/sc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Adapted sport effect on postural control after spinal cord injury PE Magnani1, NR Marques2, AC Junior3,4 and DCC de Abreu1 Study design: Cross-sectional study. Objective: The aim of this study was to compare trunk muscle activation during anterior and lateral reach in athletic and sedentary individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) and able-bodied people. Settings: University Hospital—UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil. Methods: Individuals with complete traumatic SCI and thoracic neurological level were separated into two groups: sedentary (SSCI: n = 10) and physically active (PASCI: n = 10). The control group (C: n = 10) without SCI was assessed. Trunk muscle activation was recorded during reach and grasp tasks. The significant level was set at Po0.05. Results: The control group showed a highest mean activation for left longissimus muscle during all activities (Po0.05). The PASCI group presented significant highest activation for left iliocostalis muscles during all activities, except in the anterior reach task of 90% maximum reach (anterior reach (AR) 75: P = 0.02; right lateral reach (RLR) 75: P = 0.03; RLR90: P = 0.01). The SSCI group presented highest activation for the left iliocostalis during the right lateral reach task of 75 and 90% maximum reach and right iliocostalis during the anterior reach task of 75% maximum reach (AR75: P = 0.007; RLR75: P = 0.02; RLR90: P = 0.03). A different pattern of muscle activation between the control group and the groups with SCI was observed. -

Chapter 7 Body Systems

Deep Muscles of the Back and Posterior Neck 1 Responsible for neck and head extension, lateral flexion, and rotation Affect trunk movements Play a role in maintaining proper spinal curve Complex column extending from sacrum to skull In these areas, massage is most effective when applied with a slow, sustained, broad-based compressive force. 2 Superficial group of back muscles 3 Intermediate group of back muscles – serratus posterior muscles 4 Deep group of back muscles – erector spinae muscles 5 Deep group of back muscles – transversospinales and segmental muscles and suboccipital muscles 6 Deep Posterior Cervical Muscles Splenius capitis and splenius cervicis What is the referred pain pattern of the splenius capitis and splenius cervicis? To the top of the skull, the eye, and the shoulder. 8 Vertical Muscles Erector Spinae Group I Iliocostalis lumborum, iliocostalis thoracis, and iliocostalis cervicis What is the isometric function of the iliocostalis lumborum, iliocostalis thoracis, and iliocostalis cervicis? These muscles stabilize the spine and pelvis. 9 Vertical Muscles Erector Spinae Group II Longissimus thoracis, longissimus cervicis, and longissimus capitis Longissimus means “the longest”; the muscles pictured on the left relate to the thorax, neck, and head, respectively. 10 Spinalis thoracis, spinalis cervicis, and spinalis capitis What are the referred pain patterns of the spinalis thoracis, spinalis cervicis, and spinalis capitis? The scapular, lumbar, abdominal, and gluteal areas. Oblique Muscles Transversospinales Group I Semispinalis thoracis, semispinalis cervicis, and semispinalis capitis 12 Multifidus What does multifidus mean? Many split parts. What is the eccentric function of the semispinalis thoracis, semispinalis cervicis, and semispinalis capitis? These muscles engage in flexion and contralateral lateral flexion of the trunk, neck, and head. -

Oblique and Lateral Impact Response Characteristics of A

OBLIQUE AND LATERAL IMPACT RESPONSE CHARACTERISTICS OF A DENUDED PMHS THORAX A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Bachelors in Science with Distinction in the Undergraduate School of The Ohio State University By, Geoff Brown ************ The Ohio State University 2008 Honors Examination Committee: Dr. John Bolte, IV, Advisor Dr. James Schmiedeler Approved by _________________________ Advisor Department of Mechanical Engineering Abstract Thoracic trauma is directly responsible for 25% of all trauma related fatalities and indirectly contributes to another 25%. Since most thoracic trauma is caused by automobile crashes, the need for accurate data regarding thoracic impact grows continuously as more and more cars are on the road. Many of these automobile crashes are side impacts, which lead to a primary direction of force on the person inside to be oblique and anterior to lateral. The purpose of this project is to determine the response of a denuded human thorax to oblique and lateral blunt force impacts. Specifically the project will focus on the linear and rotational stiffness characteristics of a denuded post-mortem human subject (PMHS) thorax. There is a lack of data regarding anterior oblique and posterior oblique thoracic impact response characteristics and this project will focus on obtaining the response of the PMHS thorax to these types of impacts. The current impact tests and anthropomorphic test devices (ATDs) account for frontal and lateral direction crashes only. Response in the oblique direction was previously assumed to be similar to lateral responses, but new research has shown that this may not be the case. This project consisted of both designing the fixture to be used to support the thorax during testing as well as the experimentation and analysis of the results. -

Novel Dissection Approach of Equine Back Muscles

Published: November 19, 2018 RESEARCH ARTICLE Citation: Elbrønd V. et al. (2018). Novel dissection approach of equine back muscles: Novel dissection approach of equine back muscles: new advances in new advances in anatomy and topography - and anatomy and topography - and comparison to present literature. comparison to present literature. Science Publishing Group Journal Rikke Mark Schultz1, DVM, Vibeke Sødring Elbrønd2, DVM, Ph.D. 1(2). Author’s affiliations: Corresponding Author: 1. Equine Practice, Karlebovej 22, DK- 2980 Kokkedal. Vibeke Elbrønd Dept. of Animal and Veterinary 2. Dept. of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Vet. Faculty, SUND, Sciences, Vet. Faculty, SUND, KU, KU, Denmark Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Keywords: back muscles, Knowledge of the anatomy and topography of the equine back are topography, m. iliocostalis, m. essential for a correct diagnosis and treatment as well as longissimus dorsi, m. spinalis communication among therapists, especially since different authors have not always agreed upon the anatomical topography of the epaxial back muscles. In this study, we performed a novel 3-D dissection procedure that focused on maintaining the integrity of the myofascial role in muscle topography. A total of 17 horses were carefully dissected, recorded and videotaped. The results revealed some interesting points. 1) The iliocostalis muscle (IL) was found to be clearly distinct from the longissimus dorsi muscle (LD) and positioned ventral to the lateral edge of LD. 2) Two distinct variations in the origin of the IL, i) from the Bogorozky tendon and the ventral epimysium of m. longissimus dorsi (LD) at the caudo-lateral region at L1 to L5, and ii) from the lumbar myofascia lateral to the lumbar transverse processes at the level of L2 to L4 have been found. -

The Anatomy and Pathophysiology of the CORE

Robert A. Donatelli The Anatomy and Pathophysiology of the CORE LEARNING OBJECTIVES design a rehabilitation program to promote an increase in After studying this lesson, the reader will be able to do the strength, power, and endurance specific to the muscles and following: joints that are in a state of dysfunction. Specificity of the reha- 1. Define the hip and trunk CORE bilitation program can help the athlete overcome muscu- 2. Evaluate the CORE muscles and structure loskeletal system deficits and achieve maximum potentials of 3. Delineate the difference between local and global muscles his or her talents. A combination of power, strength, and on the back endurance is critical for the muscles of the CORE to allow the 4. Identify the muscles of the abdominal area that are con- athlete to perform at his or her maximum capabilities. sidered stabilizing The lower quadrant CORE is identified by the muscles, 5. Identify the spinal muscles that stiffen the spine ligaments, and fascia that produce a synchronous motion and 6. Evaluate the CORE dysfunction stability of the trunk, hip, and lower extremities. The initia- 7. Instruct patients in exercises designed to strength hip and tion of movement in the lower limb is a result of activation of trunk muscles certain muscles that hold onto bone, referred to as stabilizers, 8. Identify the correlation between muscle weakness in the and other muscles that move bone, referred to as mobilizers. The hip and lower extremity injuries muscle action within the CORE depends on a balanced activity of the stabilizers and mobilizers. If the stabilizers do not hold onto the bone, the mobilizing muscles will function at a dis- INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITION advantage. -

Dynamic Evaluation of the Contractile Function of Lumbodorsal Muscles

Liu et al. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation (2021) 13:87 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-021-00313-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Dynamic evaluation of the contractile function of lumbodorsal muscles during locust pose in yoga by real-time ultrasound Wenfen Liu1,2,3†, Jiachun Li4†, Xiang Zhou5, Ningning Chen4, Hui Ouyang6, Zuofeng Xu3* and Yongsheng Zhu2,7* Abstract Background and Purpose: Chronic low back pain (CLBP), which has a close relationship with lumbar muscle degeneration, can be effectively treated by exercise therapy, and yoga has been widely accepted by clinicians and patients with CLBP. The purpose of this study was to observe the changes in the thickness of lumbodorsal muscles that occur during locust pose in yoga and how these changes occur. From the changes in muscle thickness that occur in the locust pose, the contractile function of lumbodorsal muscles can be evaluated. Methods: Fifty-two healthy volunteers (from May 2019 to August 2019, age from 28 to 68 years, 23 males and 29 females (age: 40 ± 8 years; weight: 68.3 ± 5.2 kg; height: 170.2 ± 13.1 cm) were recruited, and lumbodorsal muscle, including the multifidus, longissimus, iliocostalis, and quadratus lumborum, ultrasonic examinations were carried out in the relaxed and contracted states. The changes in the thickness of the lumbodorsal muscles in the relaxed and contracted states were dynamically observed by real-time ultrasound when subjects were performing the locust yoga pose. Then, the thicknesses of the muscles during the two states were measured to calculate the ratio of contraction of each muscle and determine the statistical significance of the change in thickness of each muscle.