EDISON's Warriors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz Documentary

Jazz Documentary - A Great Day In Harlem - Art Kane 1958 this probably is the greatest picture of that era of musicians I think ever taken and I'm so proud of it because now it's all over the United States probably the world very something like that it was like a family reunion you know being in one spot but all these great jazz musicians at one time I mean we call big dogs I mean the Giants were there press monk I looked around and it was count face charlie means guff Smith Jessica let's be jolly nice hit oh my my can you imagine if everybody had their instruments and played [Music] back in 1958 when New York was still the jazz capital of the world you could hear important music all over town representing an extraordinary range of periods of styles this film is a story of a magic moment when dozens of the greatest jazz stars of all time gathered for an astonishing photograph whose thing started I guess in the summer of 1958 at which time I was not a photographer art Kane went from this day to become a leading player in the field of photography this was his first picture it was our director of Seventeen magazine he was one of the two or three really great young art directors in New York attack Henry wolf and arcane and one or two other people were really considered to be big bright young Kurtz Robert Benton had not yet become a celebrated Hollywood filmmaker he had only just become Esquires new art director hoping to please his jazz fan boss with an idea for an all jazz issue but his inexperience combined with pains and experience gave -

Annual Report 2016

Collecting Exhibiting Learning Connecting Building Supporting Volunteering & Publishing & Interpreting & Collaborating & Conserving & Staffing 2016 Annual Report 4 21 10 2 Message from the Chair 3 Message from the Director and the President 4 Collecting 10 Exhibiting & Publishing 14 Learning & Interpreting 18 Connecting & Collaborating 22 Building & Conserving 26 Supporting 30 Volunteering & Staffing 34 Financial Statements 18 22 36 The Year in Numbers Cover: Kettle (detail), 1978, by Philip Guston (Bequest of Daniel W. Dietrich II, 2016-3-17) © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy McKee Gallery, New York; this spread, clockwise from top left: Untitled, c. 1957, by Norman Lewis (Purchased with funds contributed by the Committee for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, 2016-36-1); Keith and Kathy Sachs, 1988–91, by Howard Hodgkin (Promised gift of Keith L. and Katherine Sachs) © Howard Hodgkin; Colorscape (detail), 2016, designed by Kéré Architecture (Commissioned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for The Architecture of Francis Kéré: Building for Community); rendering © Gehry Partners, LLP; Inside Out Photography by the Philadelphia Museum of Art Photography Studio A Message A Message from the from the Chair Director and the President The past year represented the continuing strength of the Museum’s leadership, The work that we undertook during the past year is unfolding with dramatic results. trustees, staff, volunteers, city officials, and our many valued partners. Together, we Tremendous energy has gone into preparations for the next phase of our facilities have worked towards the realization of our long-term vision for this institution and a master plan to renew, improve, and expand our main building, and we continue reimagining of what it can be for tomorrow’s visitors. -

The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery Online

XumZy [Read now] The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery Online [XumZy.ebook] The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top- Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery Pdf Free Rick Beyer, Elizabeth Sayles DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub #19765 in Audible 2016-01-08Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishRunning time: 252 minutes | File size: 67.Mb Rick Beyer, Elizabeth Sayles : The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery: 46 of 46 people found the following review helpful. A MUST READ FOR ANY FAN OF WWIIBy RC MayerImagine, captured German maps showing 15,000 Allied troops in a location that there were no troops. Imagine, Nazirsquo;s keeping their soldiers out of position opposite what they think are thousand of enemy troops. Imagine, they can hear the US tanks lining up on the opposite riverbank. They can even here the soldiers yell ldquo;Hey Private! Put out that cigarette! Therersquo;s gas tanks over there!rdquo; Imagine, Nazi civilian spys transmitting radio broadcasts to Berlin that they overheard conversations in a pub in from soldiers in 4th Infantry Division that they were moving into Metz this evening. -

Annual Report 2018

2018 Annual Report 4 A Message from the Chair 5 A Message from the Director & President 6 Remembering Keith L. Sachs 10 Collecting 16 Exhibiting & Conserving 22 Learning & Interpreting 26 Connecting & Collaborating 30 Building 34 Supporting 38 Volunteering & Staffing 42 Report of the Chief Financial Officer Front cover: The Philadelphia Assembled exhibition joined art and civic engagement. Initiated by artist Jeanne van Heeswijk and shaped by hundreds of collaborators, it told a story of radical community building and active resistance; this spread, clockwise from top left: 6 Keith L. Sachs (photograph by Elizabeth Leitzell); Blocks, Strips, Strings, and Half Squares, 2005, by Mary Lee Bendolph (Purchased with the Phoebe W. Haas fund for Costume and Textiles, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017-229-23); Delphi Art Club students at Traction Company; Rubens Peale’s From Nature in the Garden (1856) was among the works displayed at the 2018 Philadelphia Antiques and Art Show; the North Vaulted Walkway will open in spring 2019 (architectural rendering by Gehry Partners, LLP and KXL); back cover: Schleissheim (detail), 1881, by J. Frank Currier (Purchased with funds contributed by Dr. Salvatore 10 22 M. Valenti, 2017-151-1) 30 34 A Message from the Chair A Message from the As I observe the progress of our Core Project, I am keenly aware of the enormity of the undertaking and its importance to the Museum’s future. Director & President It will be transformative. It will not only expand our exhibition space, but also enhance our opportunities for community outreach. -

Ghost Army Generic Release

New Documentary Reveals the Amazing Story of the Secret WWII Unit That Duped Hitler’s Army — With Rubber Tanks, Sound Effects and Multimedia Illusions War, deception and art come together in Rick Beyer’s documentary The Ghost Army, the astonishing true story of American G.I.s — many of whom would go on to have illustrious careers in art, design and fashion — who tricked the enemy with rubber tanks, sound effects, and carefully crafted illusions during the Second World War. The Ghost Army tells a remarkable story of a top-secret mission that was at once absurd, deadly and amazingly effective. An inflatable tank designed to fool German soldiers. Credit: National Archives In the summer of 1944, a handpicked group of G.I.s landed in France to conduct a special mission. Armed with truckloads of inflatable tanks, a massive collection of sound effects records, and more than a few tricks up their sleeves, their job was to create a traveling road show of deception on the battlefields of Europe, with the German Army as their audience. From Normandy to the Rhine, the 1100 men of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known as the Ghost Army, conjured up phony convoys, phantom divisions, and make-believe headquarters to fool the enemy about the strength and location of American units. Every move they made was top secret and their story was hushed up for decades after the war’s end. Each deception required that they impersonate a different (and vastly larger) U.S. unit. Like actors in a repertory theater, they would mount an ever-changing multimedia show tailored to each deception. -

Newyork-Presbyterian Hospital Annual Report

Letters from Home 2006-2007 Annual Report NEWYORK-PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL Important Telephone Numbers THE ALLEN PAVILION OF NEWYORK-PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL NEWYORK-PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL/ WEILL CORNELL MEDICAL CENTER General Information (212) 932-4000 Patient Information (212) 932-4300 General Information (212) 746-5454 Admitting (212) 932-5079 Patient Information (212) 746-5000 Emergency Department (212) 932-4245 Admitting (212) 746-4250 Patient Services (212) 932-4321 Ambulance Services Dispatcher (212) 472-2222 Development (212) 821-0500 Emergency Department NEWYORK-PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL/ Adult (212) 746-5050 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER Pediatric (212) 746-3300 General Information (212) 305-2500 Psychiatry (212) 746-0711 Patient Information (212) 305-3101 Human Resources (212) 746-1409 Admitting Marketing (212) 585-6800 Main Reception (212) 305-7091 NewYork-Presbyterian Sloane Hospital for Women (212) 342-1759 Healthcare System (212) 746-3577 Ambulance Services Dispatcher (212) 305-9999 Patient Services (212) 746-4293 Development (212) 342-0799 Physician Referral Service (800) 822-2694 Emergency Department Psychiatry, Payne Whitney Manhattan Adult (212) 305-6204 Referrals and Evaluation (888) 694-5700 Pediatric (212) 305-6628 General Information (212) 746-5700 Psychiatry (212) 305-6587 Public Affairs (212) 821-0560 Human Resources (212) 305-5625 Marketing (212) 821-0634 WESTCHESTER DIVISION OF NEWYORK-PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL Patient Services (212) 305-5904 Physician Referral Service (877) NYP-WELL General Information (914) 682-9100 Public Affairs (212) 305-5587 Payne Whitney Westchester Referrals and Evaluation (888) 694-5700 MORGAN STANLEY CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Table of Contents OF NEWYORK-PRESBYTERIAN Physician Referral (800) 245-KIDS Letters from Home — 2 General Information (212) 305-KIDS Patient Information (212) 305-3101 Noteworthy — 24 Admitting (212) 305-3388 Leadership Report — 26 Emergency Department (212) 305-6628 Facts and Financials — 31 Dr. -

Thoughts About Paintings Conservation This Page Intentionally Left Blank Personal Viewpoints

PERSONAL VIEWPOINTS Thoughts about Paintings Conservation This page intentionally left blank Personal Viewpoints Thoughts about Paintings Conservation A Seminar Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 EDITED BY Mark Leonard THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES & 2003 J- Paul Getty Trust THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Timothy P. Whalen, Director Los Angeles, CA 90049-1682 Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, www.getty.edu Field Projects and Science Christopher Hudson, Publisher The Getty Conservation Institute works interna- Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief tionally to advance conservation and to enhance Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Manuscript Editor and encourage the preservation and understanding Jeffrey Cohen, Designer of the visual arts in all of their dimensions— Elizabeth Chapín Kahn, Production Coordinator objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas scientific research; education and training; field Printed in Hong Kong by Imago projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. Library of Congress In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed Cataloging-in-Publication Data to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation Personal viewpoints : thoughts about paintings practice. conservation : a seminar organized by The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 /volume editor, Mark Leonard, p. -

De Ghost Army En De Tweede Wereldoorlog: Misleiding Werd Een Onderdeel Van De Amerikaanse Oorlogvoering

[‘By a marvelous system of camouflage, a complete tactical surprise was achieved in the desert’ – Winston Churchill] De Ghost Army en de Tweede Wereldoorlog Misleiding werd een onderdeel van de Amerikaanse oorlogvoering Tom Hovestad Inhoud Inleiding ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Werking van misleiding ........................................................................................................................... 5 Het Amerikaanse leger en misleiding ...................................................................................................... 7 23rd headquarters Special Troops ........................................................................................................ 10 Probleemstelling .................................................................................................................................... 12 Vraagstelling .......................................................................................................................................... 12 Opzet scriptie ........................................................................................................................................ 12 1. Militaire misleiding en het Amerikaanse leger .............................................................................. 14 Militaire misleiding ........................................................................................................................... -

Ellsworth Kelly : a Retrospective

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/ellswoOOkell ELLSWORTH KELLY ELLSWORTH KELLY: A RETROSPECTIVE Edited by Diane Waldman GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM Guggenheim Foundation, ELLSWORTH KELLY: A RETROSPECTIVE ©1996 The Solomon R. New York. All rights reserved. Organized by Diane Waldman Kelly. All Ellsworth Kell) works ©1996 Ellsworth Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Used by permission. All rights reserved. October 18, 1996-January 15, 1997 ISBN 0-8 HN hS c>~-5 (hardcover) The Museum of ( ontemporary Vrt, I os Angeles ISBN 0-8920- 177-x (softcover) February 16-May is. 1997 Guggenheim Museum Publications rallery, L ondon 1D"1 Fifth Avenue |une 12-September 7, 1997 New York, New York 10 1 2* Haus der Kunst, Munich Hardeover edition distributed In November 1997-Januarj 1998 Harry N. Abr.ims, Inc. 100 Fifth Avenue Nev. York. Nev. York 10011 Design In Matsumoto Incorporated, New York Cover by Ellsworth Kelly Printed m Germany by C antz 10 Ellsworth Kelly Contents Diane Waldman 40 Ellsworth Kelly's Multipanel Paintings Roberta Bernstein 56 Ellsworth Kelly's Curves Carter Ratcliff 62 Experiencing Presence Mark Rosenthal oloi Kelly's "1 ine, Form and ( 66 At Play with Vision: Ellsworth Clare Bell 81 Painting and Sculpture 2 5 3 Works on Paper 3 1 3 Chronology 320 Exhibition History and Bibliography Josette Lamoureux 333 Index of Reproductions This exhibition is sponsored by HUGO BOSS provided by Significant additional support lias been The Riggio Family and Stephen and Nan Swid. part by grants from the 1 his project is supported in National Endowment tor the Arts and The Owen Cheatham Foundation. -

Annual Report

July 1, 2007–June 30, 2008 AnnuAl RepoRt 1 Contents 3 Board of Trustees 4 Trustee Committees 7 Message from the Director 12 Message from the Co-Chairmen 14 Message from the President 16 Renovation and Expansion 24 Collections 55 Exhibitions 60 Performing Arts, Music, and Film 65 Community Support 116 Education and Public Programs Cover: Banners get right to the point. After more than 131 Staff List three years, visitors can 137 Financial Report once again enjoy part of the permanent collection. 138 Treasurer Right: Tibetan Man’s Robe, Chuba; 17th century; China, Qing dynasty; satin weave T with supplementary weft Prober patterning; silk, gilt-metal . J en thread, and peacock- V E feathered thread; 184 x : ST O T 129 cm; Norman O. Stone O PH and Ella A. Stone Memorial er V O Fund 2007.216. C 2 Board of Trustees Officers Standing Trustees Stephen E. Myers Trustees Emeriti Honorary Trustees Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Virginia N. Barbato Frederick R. Nance Peter B. Lewis Joyce G. Ames President James T. Bartlett Anne Hollis Perkins William R. Robertson Mrs. Noah L. Butkin+ James T. Bartlett James S. Berkman Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Elliott L. Schlang Mrs. Ellen Wade Chinn+ Chair Charles P. Bolton James A. Ratner Michael Sherwin Helen Collis Michael J. Horvitz Chair Sarah S. Cutler Donna S. Reid Eugene Stevens Mrs. John Flower Richard Fearon Dr. Eugene T. W. Sanders Mrs. Robert I. Gale Jr. Sarah S. Cutler Life Trustees Vice President Helen Forbes-Fields David M. Schneider Robert D. Gries Elisabeth H. Alexander Ellen Stirn Mavec Robert W. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

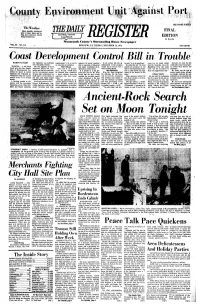

Ancient-Rock Search Set on Moon Tonight SPACE CENTER, Houston Third Apollo Spaceman, Ron- Miles of the Moon's Surface

Port SEE STORY PAGE 3 The Weather Rain, possibly starting as -FINAL snow or sleet,, today and en- ding late tomorrow. Slowly Krri Bank, Freehold •rising temperatures. Ixmg Branch EDITION 32 PAGES Monmouth County's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOL 95 NO. 114 ,- RED BANK, NJ. TUESDAY, DECEMBER 12,1972 TEN CENTS wiinMiiiriiiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiitiriiiMiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiii MiiiiiiiiiiiiiiifiiiiiiMiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiiiiniMii imiiiiii MiiiiiitiiiiiifiiMitDiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiiiiiiiriMiiiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitniiiiiiii Development Control Bill in Trouble By BEN VAN VLIET the legislation was definitely compromises" if it is ever to approval for major construe-- In the earlier bill, the ad- he said, "is to do something." came law he would resign Because, he said, the bill not in the public interest. be voted out of committee. tion or expansion of industrial ministration of the program He called the bill "the most from the Assembly, leave the would take away from proper- TRENTON - A bill which The vast majority of the 38 Won't Release and major residential devel- would have rested with a significant proposal in the Republican Party and would ty owners their liberty and would give the state Depart- witnesses before the com- "This bill in its present opments in coastal areas. three-member board. field of environmental protec- work "for the overthrow of prosperity. ; ment of Environmental Pro- mittee said the bjll would viol- form," he said, "would never It is similar to a bill pro- Sees Difficulties tion to come before any legis- those who supported the bill." Mr. Black was the first of tection the power to control ate the time-honored concept be released from committee posed last year by Mr.