Floral Response to Rapid Warming in the Earliest Eocene and Implications for Concurrent Faunal Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter H. Griggs

STRATIGRAPHIC SIGNIFICANCE OF FOSSIL POLLEN AND SPORES OF THE CHUCKANUT FORMATION, NORTHWEST WASHINGTON Thosis far the Degree of. M. S. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSI'I’Y Peter H. Griggs 1965 ~-.. 'Wfi— wwWWL ‘1. .Illilllflu‘fllllf -Jnl.| IEI‘II‘I'IIIIVFI (II 'llllll‘lll.‘ I, l {III-III! I’lII 'II (III! III, [I , . III! [III [I I'll! (III. (I ABSTRACT STRATIGRAPHIC SIGNIFICANCE OF FOSSIL POLLEN AND SPORES OF THE CHUCKANUT FORMATION, NORTHWEST WASHINGTON by Peter H. Griggs The Chuckanut Formation, a series of strongly folded, terrestrial sandstones and shales, outcrops in northwestern Washington. The rocks have been previously assigned an age of Upper Cretaceous to lower Eocene based upon plant megafossils. The microfossil flora of the standard section along the east shore of Samish Bay was examined in order to determine the relationship of the Chuckanut to the Burrard (middle Eocene) of British Columbia. A zonation and envir- onmental interpretation of the standard section was desired for further refinement of the geological history of Tertiary rocks in the Pacific Northwest. Twenty—two samples, representing 9,H8u feet of section, were examined for palynomorphs. Data were collected for both relative frequency and stratigraphic analysis. Seventy— nine palynomorphs are described. The Samish Bay section is divided into three zones. The zonation is based on changes in the relative frequency f and the stratigraphic range of the palynomorphs. These ’ '_ ‘ V'II -7 r1 ' < P812631 ALL. '.,I I» ) I— (1 0'). OT changes were brought about by changing environmental and climatic conditions during the deposition of the rocks. An age of Paleocene to lower Eocene is assigned to the Samish Bay section. -

VOLCANIC INFLUENCE OVER FLUVIAL SEDIMENTATION in the CRETACEOUS Mcdermott MEMBER, ANIMAS FORMATION, SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO

VOLCANIC INFLUENCE OVER FLUVIAL SEDIMENTATION IN THE CRETACEOUS McDERMOTT MEMBER, ANIMAS FORMATION, SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO Colleen O’Shea A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August: 2009 Committee: James Evans, advisor Kurt Panter, co-advisor John Farver ii Abstract James Evans, advisor Volcanic processes during and after an eruption can impact adjacent fluvial systems by high influx rates of volcaniclastic sediment, drainage disruption, formation and failure of natural dams, changes in channel geometry and changes in channel pattern. Depending on the magnitude and frequency of disruptive events, the fluvial system might “recover” over a period of years or might change to some other morphology. The goal of this study is to evaluate the preservation potential of volcanic features in the fluvial environment and assess fluvial system recovery in a probable ancient analog of a fluvial-volcanic system. The McDermott Member is the lower member of the Late Cretaceous - Tertiary Animas Formation in SW Colorado. Field studies were based on a southwest-northeast transect of six measured sections near Durango, Colorado. In the field, 13 lithofacies have been identified including various types of sandstones, conglomerates, and mudrocks interbedded with lahars, mildly reworked tuff, and primary pyroclastic units. Subsequent microfacies analysis suggests the lahar lithofacies can be subdivided into three types based on clast composition and matrix color, this might indicate different volcanic sources or sequential changes in the volcanic center. In addition, microfacies analysis of the primary pyroclastic units suggests both surge and block-and-ash types are present. -

BULLETINS of AMERICAN PALEONTOLOGY and PALAEONTOGRAPHICA AMERICANA

8'oL HARVARD UNIVERSITY |v 1 ^J^y^ MUS. COMP. BULLETINSZOoL ^ LIBRARY OF MAR 4 *97^ HAi UNJVERi^-AMERICAN PALEONTOLOGY VOL. LXIV 1973-74 Paleontological Research Institution Ithaca, New York 14850 U. S. A. In Memoriam Orville L. Bandy 1916-1973 CONTENTS OF VOLUME LXIV Bulletin No. Pages Plates 278. Palynology of the ASmond Formation (Upper Cretaceous) Rock Springs Uplift, Wyoming. By J. Fred Stone 1-136 1-20 279. Tabulate Corals and Echinoderms from the Pennsylvanian Winterset Limestone, Hog- shooter Formation, Northeastern Oklahoma. By H. L. Strimple and J. M. Cooke 137-168 21 280. Stratigraphy and Genera of Calcareous Foraminifera cf the Fraileys Fades (Missis- sippian) of Central Kentucky. By R. G. Browne and E. R. Pohl 169-244 22-31 281. Crinoid Studies. Part I. Some Pennsylvanian Crinoids from Nebraska. Part. II. Some Permian Crinoids from Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. By R. K. Pabian and H. L. Strimple 245-338 32-41 INDEX volume. Each number is No separate index is included in the listed in the begin- indexed separately. Contents of the volume are ning of the volume. BULLETINS MUS. COMP. 200U LIBRARY OF OCT 16 19^ AMERICAN t^S«?fALEONTOLOGY (Founded 1895) Vol. 64 No. 278 PALYNOLOGY OF THE ALMOND FORMATION (UPPER CRETACEOUS), ROCK SPRINGS UPLIFT, WYOMING By J. Fred Stone 1973 Paleontological Research Institution Ithaca, New York 14850, U.S.A. PALEONTOLOGIGAL RESEARCH INSTITUTION 1972 - 73 President Daniel B. Sass Vice-President Merrill W. Haas Secretary Philip C. Wakeley Assistant Secretary Rebecca S. Harris Director, Treasurer Katherine V. W. Palmer Counsel Armand L. Adams Representative AAAS Council John Pojeta, Jr. -

Isopogon & Petrophile

A U S T R AL I A N N A T I V E P L A N T S A S S O C I A T I O N ( A U S T ) Isopogon & Petrophile Study Group Newsletter No. 22 April 2018 ISSN 1445-9493 Website http://anpsa.org.au/iso-petSG/ STUDY GROUP LEADERS/NEWSLETTER EDITORS Catriona Bate & Phil Trickett Email: [email protected] Ph: 0409 789 567 Isopogon teretifolius, Hi Vallee farm, Badgingarra WA, October 2017. See page 10 for our profile of this species. Back issues of the Isopogon and Petrophile Study Group Newsletter are available at http://anpsa.org.au/iso-petSG/IPSG-news.html Isopogon & Petrophile Study Group Newsletter April 2018 1 In this issue Editorial From our members Exchanging cuttings and seed Galls galore Cranbourne I&P Special Collection Painting I. formosus Plant profile – I. teretifolius Plant profile – P. sessilis Dryandra Woodland WA: discovering P. circinata and I. villosus Learnings from Cranbourne Special Collection A seed germination diary: I. anethifolius and P. pulchella Grafting update Seed vs cuttings: P. pedunculata Growing WA natives: experiences in the east and the west Petrophile fossils? Two names discovered In the press Financial report Dear Members, The traditional hot, dry summer reputation of Australia seems to have struck with a vengeance this year. Members have reported little useful rainfall for the entire summer with inland NSW and Victoria/South Australia suffering through one of their driest summers on record. Even here on the normally wet South Coast of NSW, we have had our driest summer since we moved here in 2010. -

The Yellowstone Paleontological Survey

E PALEONT ON O T LO S G W I O C L A L L E National Y Park The Yellowstone Service Department of the Interior Paleontological Survey SURVEY Vincent L. Santucci Yellowstone Center for Resources National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-NR-98-1 1998 How to cite this document: Santucci, V. L. 1998. The Yellowstone Paleontological Survey. Yellowstone Center for Resources, National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming,YCR-NR-98-1. Current address for Vincent L. Santucci is National Park Service, P.O. Box 592, Kemmerer, WY 83101. The Yellowstone Paleontological Survey To Lt. Col. Luke J. Barnett, III “Uncle by blood, brother in spirit!” Vincent L. Santucci Yellowstone Center for Resources National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-NR-98-1 1998 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphy .................................................................................................... 4 Fossil Chronology........................................................................................... 6 Taxonomy ..................................................................................................... 12 Localities ...................................................................................................... 15 Interpretation ................................................................................................ 19 Paleontological Resource Management....................................................... -

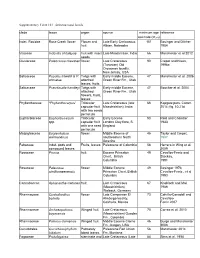

Supplementary Table 10.1. Selected Rosid Fossils Clade Taxon Organ Source Minimum Age Reference Estimate (Mya) Indet

Supplementary Table 10.1. Selected rosid fossils clade taxon organ source minimum age reference estimate (Mya) Indet. Rosidae Rose Creek flower Flower and Late Early Cretaceous 101 Basinger and Dilcher fruit Albian, Nebraska 1984 Vitaceae Indovitis chitaleyae fruit with intact Late Maastrictian, India 66 Manchester et al 2012 seeds Clusiaceae Paleoclusia chevalieri flower Late Cretaceous 90 Crepet and Nixon, (Turonian) Old 1998a Crossman locality, New Jersey, USA Salicaceae Populus tidwellii & P. Twigs with Early middle Eocene, 47 Manchester et al. 2006 wilmatae attached Green River Fm., Utah leaves, fruits Salicaceae Pseudosalix handleyi Twigs with Early middle Eocene, 47 Boucher et al. 2004 attached Green River Fm., Utah flowers, fruits, leaves Phyllanthaceae “Phyllanthocarpus” Trilocular Late Cretaceous (late 66 Kapgate pers. Comm. capsular fruit Maastrichtian), India 2014; fig. 10.21d with two seeds per locule Euphorbiaceae Euphorbiocarpon Trilocular Early Eocene 50 Reid and Chandler spp. capsular fruit London Clay flora, S. 1933 with one seed England per locule Malpighiaceae Eoglandulosa flower Middle Eocene of 45 Taylor and Crepet, warmanensis southeastern North 1987 America Fabaceae Indet. pods and Fruits, leaves Paleocene of Colombia 58 Herrera in Wing et al. compound leaves 2009 Rosaceae Prunus fruit Eocene Princeton 49 Cevallos-Ferriz and Chert, British Stockey, Columbia 1991 Rosaceae Paleorosa flower Middle Eocene 49 Basinger 1976; similkameenensis Princeton Chert, British Cevallos-Ferriz , et al Columbia 1993 Cannabaceae Aphananthe cretacea fruit Late Cretaceous 67 Knobloch and Mai (Maastrichtian) 1986 Walbeck, Germany Rhamnaceae Coahuilanthus flower Late Campanian El 73 Calvillo-Canadell and belinda Almácigo locality, Cevallos- Coahuila, Mexico Ferriz 2007 Rhamnaceae Archaeopaliurus Winged fruit Late Cretaceous 70 Correa et al. -

Geology and Paleontology of Five Cores from Screven and Burke Counties, Eastern Georgia

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geology and Paleontology of Five Cores from Screven and Burke Counties, Eastern Georgia U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1603 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Energy and the Georgia Geologic Survey USGS science for a changing world Availability of Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey Order U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) publications by calling Documents. Check or money order must be payable to the the toll-free telephone number 1-888-ASK-USGS or contact Superintendent of Documents. Order by mail from— ing the offices listed below. Detailed ordering instructions, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur Superintendent of Documents rent-year issues of the catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Government Printing Office Geological Survey." Washington, DC 20402 Books, Maps, and Other Publications Information Periodicals By Mail Many Information Periodicals products are available through Books, maps, and other publications are available by mail the systems or formats listed below: from— Printed Products USGS Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Printed copies of the Minerals Yearbook and the Mineral Com Denver, CO 80225 modity Summaries can be ordered from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office (address above). Publications include Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water- Printed copies of Metal Industry Indicators and Mineral Indus Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, try Surveys can be ordered from the Center for Disease Control Circulars, Fact Sheets, publications of general interest, single and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and copies of permanent USGS catalogs, and topographic and Health. -

Paleocene–Eocene Palynomorphs from the Chicxulub Impact Crater, Mexico

Palynology ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tpal20 Paleocene–Eocene palynomorphs from the Chicxulub impact crater, Mexico. Part 2: angiosperm pollen Vann Smith , Sophie Warny , David M. Jarzen , Thomas Demchuk , Vivi Vajda & Sean P.S. Gulick To cite this article: Vann Smith , Sophie Warny , David M. Jarzen , Thomas Demchuk , Vivi Vajda & Sean P.S. Gulick (2020) Paleocene–Eocene palynomorphs from the Chicxulub impact crater, Mexico. Part 2: angiosperm pollen, Palynology, 44:3, 489-519, DOI: 10.1080/01916122.2019.1705417 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2019.1705417 View supplementary material Accepted author version posted online: 17 Dec 2019. Published online: 23 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 138 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tpal20 PALYNOLOGY 2020, VOL. 44, NO. 3, 489–519 https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2019.1705417 Paleocene–Eocene palynomorphs from the Chicxulub impact crater, Mexico. Part 2: angiosperm pollen Vann Smitha,b , Sophie Warnya,b, David M. Jarzenc, Thomas Demchuka, Vivi Vajdad and Sean P.S. Gulicke aDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, LSU, Baton Rouge, LA, USA; bMuseum of Natural Science, LSU, Baton Rouge, LA, USA; cCleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH, USA; dSwedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden; eInstitute for Geophysics and Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas at Austin, TX, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS At the end of the Cretaceous Period, an asteroid collided with the Earth and formed the Chicxulub Mexico; Paleocene; impact structure on the Yucatan Platform. -

Yellowstone Paleontological Survey

Yellowstone Paleontological Survey Introduction Stratigraphy Fossil Chronology Taxonomy Localities Vincent L. Santucci Interpretation Paleontological Resource Management Research Collections and Curation Paleontological Resources Near Yellowstone [email protected] Bibliography Yellowstone Center for Resources Appendix A: Yellowstone Paleontological Survey Proposal National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming Appendix B: Yellowstone Paleo-Species List YCR-NR-98-1 1998 Appendix C: RMP Paleontological Project Statements Appendix D: Paleontology Researchers at Yellowstone Appendix E: Fossil Specimens in Park Collections Appendix F: Yellowstone Fossils in Outside Repositories Appendix G: GIS Stratigraphy Maps http://www2.nature.nps.gov/geology/paleontology/surveys/yell_survey/index.htm[5/28/2013 2:13:48 PM] Yellowstone Paleo Survey: Introduction Introduction A survey of Yellowstone's fossil resources was initiated in the same spirit of discovery demonstrated by Captain William Raynolds, Henry Washburn, and Ferdinand Hayden. Rumors of marine reptiles, trilobite mass death assemblages, and even dinosaurs in Yellowstone have lured a team of paleontologists in the same way that the legends of "Colter's Hell" and Jim Bridger's "Tall Tales" have attracted many before. Compared to other natural resources at Yellowstone National Park, fossils have received little attention. Except for the research conducted on the petrified forests, Yellowstone's fossils have remained a relative "paleo-incognita" more than 125 years after the park's establishment. As this survey demonstrates, the lack of paleontological research is not due to a lack of significant fossils. Perhaps historian Aubrey Haines provided the best explanation in his comment, "Past administrations preferred that resources not in the public's eye be left alone" (pers. -

Palynological Differences Between the Chuckanut and Huntingdon Formations, Northwestern Washington

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1982 Palynological Differences Between the Chuckanut and Huntingdon Formations, Northwestern Washington Kenneth Norman Reiswig Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Reiswig, Kenneth Norman, "Palynological Differences Between the Chuckanut and Huntingdon Formations, Northwestern Washington" (1982). WWU Graduate School Collection. 676. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/676 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PALYNOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE CHUCKANUT AND HUNTINGDON FORMATIONS, NORTHWESTERN WASHINGTON A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Western Washington University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for tfffe Degree Master of Science Kenneth N. Reiswig PALYNOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE CHUCKANUT AND HUNTINGDON FORMATIONS, NORTHWESTERN WASHINGTON by Kenneth N. Reiswig Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Vegetation Response to Environmental Changes

Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae (2021), vol. 91: 149–166 doi: https://doi.org/10.14241/asgp.2021.07 VEGETATION RESPONSE TO ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES BASED ON PALYNOLOGICAL RESEARCH ON THE MIDDLE MIOCENE LIGNITE AT THE JÓŹWIN IIB OPEN-CAST MINE (KONIN REGION, CENTRAL POLAND) Barbara SŁODKOWSKA 1 * & Marek WIDERA 2 1 Polish Geological Institute-National Research Institute, 4, Rakowiecka Str., 00-975 Warsaw, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Geology, A. Mickiewicz University, 12, Krygowski Str. 62-028 Poznań, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Słodkowska, B. & Widera, M., 2021. Vegetation response to environmental changes based on palynological research on the Middle Miocene lignite at the Jóźwin IIB open-cast mine (Konin region, central Poland). Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae, 91: 149–166. Abstract : Palynological research was performed on the first Mid-Polish lignite seam (MPLS-1) at the Jóźwin IIB open-cast mine. The extremely rich pollen assemblages allowed investigation of the development of phytogenic sedimentation and the succession of plant communities. The vegetation cover, representing peat accumulation and adjacent areas, was reconstructed in the homogeneous lignite seam. Despite the lack of clear macroscopic differences in the lignite lithology and a similar floristic composition, a similar succession of plant communities was observed in three repetitions in the profile. The plant communities described were grouped into five cycles. Changes in the succession resulted mainly from oscillations of the groundwater level. On the basis of the vegeta- tion composition, the climatic conditions predominant during the peat-forming sedimentation were reconstructed. Climate changes are most precisely recorded in the mixed mesophilous forest community. -

Cretaceous-Tertiary Palynology, Eastern Side of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico

MEMOIR 6 Cretaceous -Tertiary Palynology, Eastern Side of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico By ROGER Y. ANDERSON 1 9 6 0 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EX OFFICIO The Honorable John Burroughs ............................................................. Governor of New Mexico Tom Wiley ................................................................................. Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS Holm 0. Bursum, Jr. .......................................................................................................... Socorro Thomas M. Cramer ......................................................................................................... Carlsbad Frank C. DiLuzio ..................................................................................................... Albuquerque John N. Mathews, Jr. ........................................................................................................ Socorro Richard A. Matuszeski ............................................................................................. Albuquerque For Sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex.—$3.50. Contents Page ABSTRACT ......................................................... INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................