Scandinavian Kingship Transformed Succession, Acquisition and Consolidation in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion

Chapter 3 Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion 1 Introduction: Adam of Bremen and His Work “A. minimus sanctae Bremensis ecclesiae canonicus”1 – in this humble manner, Adam of Bremen introduced himself on the pages of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, yet his name did not sink into oblivion. We know it thanks to a chronicler, Helmold of Bosau,2 who had a very high opinion of the Master of Bremen’s work, and after nearly a century decided to follow it as a model. Scholarship has awarded Adam of Bremen not only with a significant place among 11th-c. writers, but also in the whole period of the Latin Middle Ages.3 The historiographic genre of his work, a history of a bishopric, was devel- oped on a larger scale only after the end of the famous conflict on investiture between the papacy and the empire. The very appearance of this trend in histo- riography was a result of an increase in institutional subjectivity of the particu- lar Church.4 In the case of the environment of the cathedral in Bremen, one can even say that this phenomenon could be observed at least half a century 1 Adam, [Praefatio]. This manner of humble servant refers to St. Paul’s writing e.g. Eph 3:8; 1 Cor 15:9, and to some extent it seems to be an allusion to Christ’s verdict that his disciples quarrelled about which one of them would be the greatest (see Lk 9:48). 2 Helmold I, 14: “Testis est magister Adam, qui gesta Hammemburgensis ecclesiae pontificum disertissimo sermone conscripsit …” (“The witness is master Adam, who with great skill and fluency described the deeds of the bishops of the Church in Hamburg …”). -

Erkebiskopene Som Fredsskapere

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Erkebiskopene som fredsskapere i det norske samfunnet fra 1202 til 1263 Tore Sævrås Masteroppgave i historie Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie Universitetet i Oslo Høsten 2010 1 Forord Nå som jeg endelig er ferdig med min masteroppgave vil jeg rette en stor takk til min veileder Jon Vidar Sigurdsson, blant annet for gode råd, spørsmål og innspill som har gjort at jeg har greid å levere denne oppgaven innenfor nomerert tid. Særlig er jeg takknemelig for den tiden du satte av de siste ukene til gjennomlesning av kapittelutkastene til denne oppgaven, og at jeg når tid som helst kunne ringe deg dersom det var et eller annet jeg slet med i oppgaven min. Jeg har selv lært mye med å skrive denne oppgaven, og selv om det til tider har vært et slit, må jeg også innrømme at det har vært veldig morsomt å jobbe med denne oppgaven det siste semesteret da jeg begynte å se hvordan oppgaven kom til å se ut. Jeg vil også rette en takk til familie og venner for den forståelse og tålmodighet de har vist meg i de siste månedene, når jeg har arbeidet med å få ferdig denne oppgaven i tide. 2 Innholdsfortegnelse Innledning s. 4 Historiografi s. 5 Kilder s.10 1: Erkebiskopenes fredsskaperrolle i de store politiske konfliktene s.14 Initiativtakeren - erkebiskopen s.15 Initiativtakeren - de stridende partene s.17 Erkebiskopene som meglere s.23 Erkebiskopenes formidlerrolle s.27 Erkebiskopen som dommer s.33 Avslutning -

Erwin Panofsky

Reprinted from DE ARTIBUS OPUSCULA XL ESSAYS IN HONOR OF ERWIN PANOFSKY Edited l!J M I L LA RD M EIS S New York University Press • I90r Saint Bridget of Sweden As Represented in Illuminated Manuscripts CARL NORDENFALK When faced with the task of choosing an appropriate subject for a paper to be published in honor of Erwin Panofsky most contributors must have felt themselves confronted by an embarras de richesse. There are few main problems in the history of Western art, from the age of manuscripts to the age of movies, which have not received the benefit of Pan's learned, pointed, and playful pen. From this point of view, therefore, almost any subject would provide a suitable opportunity for building on foundations already laid by him to whom we all wish to pay homage. The task becomes at once more difficult if, in addition to this, more specific aims are to be considered. A Swede, for instance, wishing to see the art and culture of his own country play apart in this work, the association with which is itself an honor, would first of all have to ask himself if anything within his own national field of vision would have a meaning in this truly international context. From sight-seeing in the company of Erwin Panofsky during his memorable visit to Sweden in 1952 I recall some monuments and works of art in our country in which he took an enthusiastic interest and pleasure.' But considering them as illustrations for this volume, I have to realize that they are not of the international standard appropriate for such a concourse of contributors and readers from two continents. -

De Nordiske Husebyenes Kronologi Og Ull-Navnene

De nordiske husebyenes kronologi og Ull-navnene Atle Steinar Langekiehl En av hj ørnestei nene i As ga ut Stei nnes ' avha ndli ng Husebyar er ha ns fø rste forsøk på å vise en nær fo rbindelse me llo m husebye ne ogkulte n for gu de n Ull. Me ns Stei nnes hevdet at huseby -i ns titusjonenoppstod ca. år 625 e.kr. i det uppsve nske se ntralo mrådet ved Malare n, har ny ere sve ns k fo rsk ni ng villet tidfeste huseby -o rganisasjo nene i det sa mme området til l!00- ogbe gynne lse nav 1200- åre ne. Da Stei nnes me nt e husebye ne oppstod i Uppla nd, ville enslik dateri ng fje rne ethvert gr u nnla g for ha ns hypotese om at dyrk ni ngenav Ull ka n knyttes til disse ad ministrative se ntre ne. Huseby -o rganisasjo nene målikevel være langt eld reen nde ntidf esti nge nen kelte sve nske fo rske re nå"bevder for husebye ne i Uppla nd. Side n kro nolo giener et helt se ntralt pu nkt når det gjelder de no rdiske husebye ne, er det all grunntil åse nær me re både påSte innes ' hy pot ese omhusebye nes ti lknytningtil Ull -kultus en ogan dre sid erved ha ns argu me nt asj on. Asgaut Steinnes' avhandling Husebyar fra 19551 er i Norge blitt stående som den grunnleggende studien om de administrative sentrene vi kaller husebyer . Det gjenspeilerseg ikke minst i hvorledes selv de nyeste norske bygdebøkene refererer til Steinnes' hypoteser når de skildrer huseby-institusjonens opphav og historie. -

Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire

HUNNIC WARFARE IN THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CENTURIES C.E.: ARCHERY AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE A Thesis Submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Laura E. Fyfe 2016 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2017 ABSTRACT Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire Laura E. Fyfe The Huns are one of the most misunderstood and mythologized barbarian invaders encountered by the Roman Empire. They were described by their contemporaries as savage nomadic warriors with superior archery skills, and it is this image that has been written into the history of the fall of the Western Roman Empire and influenced studies of Late Antiquity through countless generations of scholarship. This study examines evidence of Hunnic archery, questions the acceptance and significance of the “Hunnic archer” image, and situates Hunnic archery within the context of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. To achieve a more accurate picture of the importance of archery in Hunnic warfare and society, this study undertakes a mortuary analysis of burial sites associated with the Huns in Europe, a tactical and logistical study of mounted archery and Late Roman and Hunnic military engagements, and an analysis of the primary and secondary literature. Keywords: Archer, Archery, Army, Arrow, Barbarian, Bow, Burial Assemblages, Byzantine, Collapse, Composite Bow, Frontier, Hun, Logistics, Migration Period, Roman, Roman Empire, Tactics, Weapons Graves ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. -

The Swedish Approach to Fairness

FACTS ABOUT SWEDEN | GENDER EQUALITY sweden.se PHOTO: MELKER DAHLSTRAND/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE PHOTO: The Swedish welfare system, which entitles both men and women to paid parental leave, has been central in promoting gender equality in Sweden. GENDER EQUALITY: THE SWEDISH APPROACH TO FAIRNESS Gender equality is one of the cornerstones of Swedish society. The aim of Sweden’s gender equality policies is to ensure that women and men enjoy the same opportunities, rights and obligations in all areas of life. The overarching principle is that every- areas of economics, politics, education school level onwards, with the aim of one, regardless of gender, has the right and health. Since the report’s inception, giving children the same opportunities to work and support themselves, to bal- Sweden has never finished lower than in life, regardless of their gender, by ance career and family life, and to live fourth in the Gender Gap rankings, which using teaching methods that counteract without the fear of abuse or violence. can be found at www.weforum.org. traditional gender patterns and gender Gender equality implies not only equal roles. distribution between men and women Gender equality at school Today, girls generally have better in all domains of society. It is also about Gender equality is strongly emphasised grades in Swedish schools than boys. the qualitative aspects, ensuring that in the Education Act, the law that gov- Girls also perform better in national the knowledge and experience of both erns all education in Sweden. It states tests, and a greater proportion of girls men and women are used to promote that gender equality should reach and complete upper secondary education. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

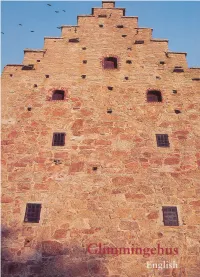

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

Even Ballangrud Andersen

Makt og maktsentre i vikingtid og middelalder Maktsentre på Østlandet fra ca. 800 til 1200 e. Kr. i Snorre og arkeologiske kilder Even Ballangrud Andersen Masteroppgave i historie Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie Universitetet i Oslo Vår 2012 1 Forord Jeg må selvfølgelig først takke min veileder professor Jon Vidar Sigurdsson for uvurderlig hjelp underveis i skrivingen av denne oppgaven. Takk også til medstudenter fra masterstudiet ved UiO og til kollegaer både ved Kommunearkivet i Fredrikstad og i Fredrikstad kommune ellers som har vært hjelpsomme og/eller har vist interesse for mine studier og undersøkelse. Kart over de mest kjente stormannsgårdene i vikingtidens Norge. Kilde: Kartet er hentet fra Kleivane (1981:129) og hans oversikt over lendmannsgårder i Norge. 2 Innholdsfortegnelse: 1. Maktstrukturene – undersøkelsens rammeverk – side 4 1.1 Problemstilling – side 4 1.2 Teoretisk fundament og rammeverk – side 6 1.3 Metode – side 8 1.4 Historiografi – side 9 1.5 Kilder – side 14 1.5.1 Skriftlige kilder – side 14 1.5.2 Arkeologiske kilder – side 17 1.5.3 Kildekritikk og de skriftlige kildene – side 19 2. Maktstrukturer og maktsentre i Østfold – side 22 2.1 Østfold og dets maktsentre i Snorre – side 23 2.1.1 Snorre forteller – side 23 2.1.2 Konkluderende bemerkninger til Snorres Østfold – side 32 2.2 Maktsentre i indre og ytre Østfold – side 33 2.2.1 Alvheim og Vingulmorkriket – side 33 2.2.2 Kongsgården Alvheim og dens omland – side 43 2.2.3 Alvheim og rikssamlingen – side 49 2.2.4 Maktsenteret Alvheim og vikingtidens stormanssamfunn – side 53 2.3 Maktsenteret Borg – side 55 2.3.1 Borg – side 56 2.3.2 Tingsted – side 57 2.3.3 Kirkens tilstedeværelse i Borg – side 57 2.3.4 Borg - maktsenter i middelalderens norske kongedømme – side 60 3. -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities. -

Prisoners of War in the Baltic in the XII-XIII Centuries

Prisoners of war in the Baltic in the XII-XIII centuries Kurt Villads Jensen* University of Stockholm Abstract Warfare was cruel along the religious borders in the Baltic in the twelfth and thirteenth century and oscillated between mass killing and mass enslavement. Prisoners of war were often problematic to control and guard, but they were also of huge economic importance. Some were used in production, some were ransomed, some held as hostages, all depending upon status of the prisoners and needs of the slave owners. Key words Warfare, prisoners of war. Baltic studies. Baltic crusades. Slavery. Religious warfare. Medieval genocide. Resumen La guerra fue una actividad cruel en las fronteras religiosas bálticas entre los siglos XII y XIII, que osciló entre la masacre y la esclavitud en masa. El control y guarda de los prisioneros de guerra era frecuentemente problemático, pero también tenían una gran importancia económica. Algunos eran empleados en actividades productivas, algunos eran rescatados y otros eran mantenidos como rehenes, todo ello dependiendo del estatus del prisionero y de las necesidades de sus propietarios. Palabras clave Guerra, prisioneros de guerra, estudios bálticos, cruzadas bálticas, esclavitud, guerra de religión, genocidio medieval. * Dr. Phil. Catedrático. Center for Medieval Studies, Stockholm University, Department of History, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.journal-estrategica.com/ E-STRATÉGICA, 1, 2017 • ISSN 2530-9951, pp. 285-295 285 KURT VILLADS JENSEN If you were living in Scandinavia and around the Baltic Sea in the high Middle Ages, you had a fair change of being involved in warfare or affected by war, and there was a considerable risk that you would be taken prisoner. -

The Conversion of Scandinavia James E

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1978 The ah mmer and the cross : the conversion of Scandinavia James E. Cumbie Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Cumbie, James E., "The ah mmer and the cross : the conversion of Scandinavia" (1978). Honors Theses. Paper 443. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES 11111 !ill iii ii! 1111! !! !I!!! I Ill I!II I II 111111 Iii !Iii ii JIJ JIJlllJI 3 3082 01028 5178 .;a:-'.les S. Ci;.r:;'bie ......:~l· "'+ori·.:::> u - '-' _.I".l92'" ..... :.cir. Rillin_: Dr. ~'rle Dr. :._;fic:crhill .~. pril lJ, 197f' - AUTHOR'S NOTE The transliteration of proper names from Old Horse into English appears to be a rather haphazard affair; th€ ~odern writer can suit his fancy 'Si th an~r number of spellings. I have spelled narr.es in ':1ha tever way struck me as appropriate, striving only for inte:::-nal consistency. I. ____ ------ -- The advent of a new religious faith is always a valuable I historical tool. Shifts in religion uncover interesting as- pects of the societies involved. This is particularly true when an indigenous, national faith is supplanted by an alien one externally introduced. Such is the case in medieval Scandinavia, when Norse paganism was ousted by Latin Christ- ianity. -

Agrarian Metaphors 397

396 Agrarian Metaphors 397 The Bible provided homilists with a rich store of "agricultural" metaphors and symbols) The loci classici are passages like Isaiah's "Song of the Vineyard" (Is. 5:1-7), Ezekiel's allegories of the Tree (Ez. 15,17,19:10-14,31) and christ's parables of the Sower (Matt. 13: 3-23, Mark 4:3-20, Luke 8:5-15) ,2 the Good Seed (Matt. 13:24-30, Mark 4:26-29) , the Barren Fig-tree (Luke 13:6-9) , the Labourers in the Vineyard (Matt. 21:33-44, Mark 12:1-11, Luke 20:9-18), and the Mustard Seed (Matt. 13:31-32, Mark 4:30-32, Luke 13:18-19). Commonplace in Scripture, however, are comparisons of God to a gardener or farmer,5 6 of man to a plant or tree, of his soul to a garden, 7and of his works to "fruits of the spirit". 8 Man is called the "husbandry" of God (1 Cor. 3:6-9), and the final doom which awaits him is depicted as a harvest in which the wheat of the blessed will be gathered into God's storehouse and the chaff of the damned cast into eternal fire. Medieval scriptural commentaries and spiritual handbooks helped to standardize the interpretation of such figures and to impress them on the memories of preachers (and their congregations). The allegorical exposition of the res rustica presented in Rabanus Maurus' De Universo (XIX, cap.l, "De cultura agrorum") is a distillation of typical readings: Spiritaliter ... in Scripturis sacris agricultura corda credentium intelliguntur, in quibus fructus virtutuxn germinant: unde Apostolus ad credentes ait [1 Cor.