Computer Science 160 Translation of Programming Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low-Power Microprocessor Based on Stack Architecture

Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Stack on based Microprocessor Low-power Master’s Thesis Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Series of Master’s theses Department of Electrical and Information Technology LU/LTH-EIT 2015-464 Department of Electrical and Information Technology, http://www.eit.lth.se Faculty of Engineering, LTH, Lund University, September 2015. Department of Electrical and Information Technology Master of Science Thesis Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Supervisors: Author: Prof. Joachim Rodrigues Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Prof. Anders Ard¨o Lund 2015 © The Department of Electrical and Information Technology Lund University Box 118, S-221 00 LUND SWEDEN This thesis is set in Computer Modern 10pt, with the LATEX Documentation System ©Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao 2015 Printed in E-huset Lund, Sweden. Sep. 2015 Abstract There are many applications of microprocessors in embedded applications, where power efficiency becomes a critical requirement, e.g. wearable or mobile devices in healthcare, space instrumentation and handheld devices. One of the methods of achieving low power operation is by simplifying the device architecture. RISC/CISC processors consume considerable power because of their complexity, which is due to their multiplexer system connecting the register file to the func- tional units and their instruction pipeline system. On the other hand, the Stack machines are comparatively less complex due to their implied addressing to the top two registers of the stack and smaller operation codes. This makes the instruction and the address decoder circuit simple by eliminating the multiplex switches for read and write ports of the register file. -

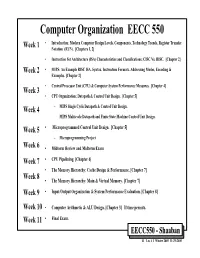

Computer Organization EECC 550 • Introduction: Modern Computer Design Levels, Components, Technology Trends, Register Transfer Week 1 Notation (RTN)

Computer Organization EECC 550 • Introduction: Modern Computer Design Levels, Components, Technology Trends, Register Transfer Week 1 Notation (RTN). [Chapters 1, 2] • Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Characteristics and Classifications: CISC Vs. RISC. [Chapter 2] Week 2 • MIPS: An Example RISC ISA. Syntax, Instruction Formats, Addressing Modes, Encoding & Examples. [Chapter 2] • Central Processor Unit (CPU) & Computer System Performance Measures. [Chapter 4] Week 3 • CPU Organization: Datapath & Control Unit Design. [Chapter 5] Week 4 – MIPS Single Cycle Datapath & Control Unit Design. – MIPS Multicycle Datapath and Finite State Machine Control Unit Design. Week 5 • Microprogrammed Control Unit Design. [Chapter 5] – Microprogramming Project Week 6 • Midterm Review and Midterm Exam Week 7 • CPU Pipelining. [Chapter 6] • The Memory Hierarchy: Cache Design & Performance. [Chapter 7] Week 8 • The Memory Hierarchy: Main & Virtual Memory. [Chapter 7] Week 9 • Input/Output Organization & System Performance Evaluation. [Chapter 8] Week 10 • Computer Arithmetic & ALU Design. [Chapter 3] If time permits. Week 11 • Final Exam. EECC550 - Shaaban #1 Lec # 1 Winter 2005 11-29-2005 Computing System History/Trends + Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Fundamentals • Computing Element Choices: – Computing Element Programmability – Spatial vs. Temporal Computing – Main Processor Types/Applications • General Purpose Processor Generations • The Von Neumann Computer Model • CPU Organization (Design) • Recent Trends in Computer Design/performance • Hierarchy -

Design and Construction of a PC-Based Stack Machine Simulator for Undergraduate Computer Science & Engineering Courses

Design and Construction of a PC-Based Stack Machine Simulator for Undergraduate Computer Science & Engineering Courses Fitratullah Khan and Sohail Anwar Department of Computer Science The University of Texas at Brownsville Brownsville, Texas 78520 Abstract - A senior level compiler design course in an top of the stack. The instructions pop operands from the stack undergraduate computer science and engineering program and push results back on to the stack. usually deals with teaching the students the basics of compiler The stack machine designed by the authors consists of a construction. A thorough understanding of the grammar of a code segment, a stack segment, an Arithmetic Logic Unit formal language and a compiler designed for it can only be (ALU), and four address registers. The code segment has the truly obtained by writing a working compiler for the language. program to be executed. The stack segment holds the A semester long feat of constructing the lexical, syntactic, intermediate data and addresses generated during program semantic, and code generation phases of a compiler exposes execution. A portion of the stack is set aside to store global the students to the inner workings of the compiler. The final data as well. The four address registers are pointers into the phase of testing the integrity and effectiveness of the code and stack segments: constructed compiler is both important and rewarding for a ! Instruction Pointer (IP) points to the next student. Furthermore, since the impetus of such an instruction to be executed, undergraduate course is to deal with the issues of compiler ! Stack Pointer (SP) points to the valid item on top construction rather than intricacies of different machines, it is of the stack, instructive to generate the code for a simple stack machine, ! Local Scope Pointer (LSP) points to the local incorporating a hardware stack, rather than dealing with a data declared within a procedure and the register-based machine such as a microcomputer. -

EECS 470 Lecture 2 Instruction Set Architecture

© Wenisch 2007 -- Portions © Austin, Brehob, Falsafi, Hill, Hoe, Lipasti, Martin, Roth, Shen, Smith, Sohi, Tyson, Vijaykumar EECS 470 Lecture 2 Instruction Set Architecture Fall 2007 Prof. Thomas Wenisch http://www.eecs.umich.edu/courses/eecs470/ Slides developed in part by Profs. Austin, Brehob, Falsafi, Hill, Hoe, Lipasti, Shen, Smith, Sohi, Tyson, Vijaykumar, and Wenisch of Carnegie Mellon University, Purdue University, University of Michigan, and University of Wisconsin. Lecture 2 EECS 470 Slide 1 © Wenisch 2007 -- Portions © Austin, Brehob, Falsafi, Hill, Hoe, Lipasti, Martin, Roth, Shen, Smith, Sohi, Tyson, Vijaykumar Announcements Reminders: HW # 1 due Friday 9/14 Hand in at start of discussion Programming assignment #1 due Friday 9/14 Electronic hand‐in by midnight Lecture 2 EECS 470 Slide 2 © Wenisch 2007 -- Portions © Austin, Brehob, Falsafi, Hill, Hoe, Lipasti, Martin, Roth, Shen, Smith, Sohi, Tyson, Vijaykumar Readings For today: Task of the Referee. A.J. Smith H & P Chapter 1 H & P Appendix B For Wednesday: Cramming More Components onto ICs. GEG.E. Moore H & P Chapter A.1‐A.6 Lecture 2 EECS 470 Slide 3 © Wenisch 2007 -- Portions © Austin, Brehob, Falsafi, Hill, Hoe, Lipasti, Martin, Roth, Shen, Smith, Sohi, Tyson, Vijaykumar Performance – Key Points Amdahl’s law Soverall = 1 / ( (1-f)+ f/S ) Iron law Time Instructions Cycles Time = × × Program Program Instruction Cycle AiThiAveraging Techniques Arithmetic Harmonic Geometric Time Rates Ratios n n 1 n n 1 n ∑i=1Timei ∏Ratio i ∑i=1 n i =1 Rate i Lecture 2 EECS 470 Slide 4 © Wenisch 2007 -- Portions © Austin, Brehob, Falsafi, Hill, Hoe, Lipasti, Martin, Roth, Shen, Smith, Sohi, Tyson, Vijaykumar Digital System Cost Cost is also a key design constraint Architecture is about trade‐offs Cost plays a major role Huge difference between Cost & Price E.g., Higher Price Æ Lower Volume Æ Higher Cost Æ Higher Price Direct Cost Gross Margin List vs. -

Code Generation for a Stack Machine •

CS 410 Lecture Outline Code Generation for a Stack Machine • a simple language • activation trees again • a simple implementation model: the stack machine • stack machine implementation of the simple • language – design of activation records – code generation Note: these lecture notes are by Alex Aiken for his compiler class at UC Berkeley with minor modifications made for local use. 1 CS 410 A Small Language A language with integers and integer operations: • P D; P D → | D def id(ARGS)=E; → ARGS id, ARGS id → | E int id if E = E then E else E → | | 1 2 3 4 | E1 + E2 E1 E2 id(E1,...,En) | − | The first function definition f is the “main” routine. • Running the program on input i means compute f(i). • Computing the ith Fibonacci number: • def fib(x) = if x = 1 then 0 else if x = 2 then 1 else fib(x-1) + fib(x-2) 2 CS 410 Review: Activation Trees The activation tree for a run of a program is a graph • of the function calls. For fib(4), the activation tree is: • fib(4) fib(3) fib(2) fib(2) fib(1) Activation records are managed using a runtime stack. • At any point during execution, the activation stack • describes some path starting from the root of the ac- tivation tree. 3 CS 410 A Stack Machine A stack machine evaluates one expression at a time. • The value of an expression is stored in a • distinguished register called the accumulator (or acc). A stack is used to hold intermediate results. • To evaluate an expression op(e ,...,e ): • 1 n 1. -

Development of Stack Based Central Processing Unit for a FORTH Computer Using FPGA

Development of Stack Based Central Processing Unit for a FORTH Computer Using FPGA By KENNETH WONG FATT KONG FINAL YEAR PROJECT REPORT Final Dissertation Submitted to the Electrical & Electronics Engineering Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Engineering (Hons) (Electrical & Electronics Engineering) DECEMBER 2009 Universiti Teknologi Petronas Bandar Seri Iskandar 31750 Tronoh Perak Darul Ridzuan Copyright 2009 by Kenneth Wong Fatt Kong, UTP CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL Development of Stack Based Central Processing Unit for a FORTH Computer Using FPGA by Kenneth Wong Fatt Kong A project Final Dissertation submitted to the Electrical & Electronics Engineering Program Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Bachelor of Engineering (Hons) (Electrical & Electronics Engineering) Approved: __________________________ __________________________ Dr. Yap Vooi Voon Mr. Patrick Sebastian Project Supervisor Project Co-Supervisor UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI PETRONAS TRONOH, PERAK December 2009 i CERTIFICATION OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that I am responsible for the work submitted in this project, that the original work is my own except as specified in the references and acknowledgements, and that the original work contained herein have not been undertaken or done by unspecified sources or persons. __________________________ Kenneth Wong Fatt Kong ii ABSTRACT This is the Final Dissertation for Electrical & Electronics Engineering Bachelor Degree Final Year Project (FYP). The title for this FYP is “Development of Stack Based Central Processing Unit for a FORTH Computer Using FPGA”. This project is based on the design by a previous FYP student, Aaron Tang Shen Lee with his title, “Development of a Stack-Based Centre Processing Unit (CPU) using TTL Logic”. -

Adapting the EPIC Register Stack for an Efficient Execution of Forth

Optimizing Intel EPIC/Itanium2 Architecture for Forth Jamel Tayeb*, Smail Niar** *Intel Corporation, Portland, Oregon (USA) **LAMIH ROI, University of Valenciennes, (France) [email protected], [email protected] Abstract makes it well suited as a proxy for more sophisticated stack machines such as .NET (The MSIL evaluation stack). In Forth is a stack machine that represents a good match addition, Forth’s key intrinsic advantages are: for the register stack of the Explicit Parallel Instruction A low memory footprint; Computer (EPIC) architecture. In this paper we will A high execution speed; introduce a new calling mechanism using the register stack The ability to interactively expand its dictionaries while to implement a Forth system more efficiently. Based upon our performance measurements, we will show that the new developing applications. calling mechanism is a promising technique to improve the performance of stack-based interpretative languages such 1.3. Why using EPIC? as Forth. The limitation in EPIC’s Register Stack Engine Itanium processors are today the only commercial chips makes the need for hardware support to improve to implement the EPIC architecture. This processor family performance and possibly close the efficiency gap with is specifically targeting the enterprise server and high- specialized stack processors. We will define also an performance computing cluster segments. With 410 million adjustment to Itanium 2 processor’s instruction set to transistors required to implement the EPIC architecture in accommodate the new calling mechanism and present a the Itanium 2 processor (9MB on-chip cache memory), one conservative architectural implementation over the current can argue that IPF doesn’t seem to be well suited for mid or Itanium 2 processor’s pipeline. -

Second-Generation Stack Computer Architecture

Second-Generation Stack Computer Architecture Charles Eric LaForest A thesis presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Independent Studies University of Waterloo Canada April 2007 ii Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this research paper. I authorize the University of Waterloo to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature: I further authorize the University of Waterloo to reproduce this research paper by photocopy- ing or other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature: The work in this research paper is based on research carried out in the Independent Studies Program at the University of Waterloo, Canada. No part of this thesis has been submitted else- where for any other degree or qualification and is all my own work unless referenced to the contrary in the text. Copyright c 2007 by Charles Eric LaForest. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotations and information derived from it must be acknowledged. iii Second-Generation Stack Computer Architecture Charles Eric LaForest Submitted for the degree of Bachelor of Independent Studies April 2007 Abstract It is commonly held in current computer architecture literature that stack-based computers were entirely superseded by the combination of pipelined, integrated microprocessors and improved compilers. While correct, the literature omits a second, new generation of stack computers that emerged at the same time. -

Introduction to Programming

Compilers Stack Machines Alex Aiken Stack Machines • Only storage is a stack • An instruction r = F(a1,…an): – Pops n operands from the stack – Computes the operation F using the operands – Pushes the result r on the stack Alex Aiken Stack Machines Alex Aiken Stack Machines • Consider two instructions – push i - push integer i on the stack – add - add two integers – A program: push 7 push 5 add Alex Aiken Stack Machines • Stack machines are a very simple machine model – Leads to a simple, small compiler – But not necessarily one that produces very fast code Alex Aiken Stack Machines • Location of the operands/result is not explicitly stated – Always the top of the stack • In contrast to a register machine – add instead of add r1, r2, r3 – More compact programs • One reason that Java bytecode uses stack evaluation Alex Aiken Stack Machines • There is an intermediate point between a pure stack machine and a pure register machine • An n-register stack machine – Conceptually, keep the top n locations of the pure stack machine’s stack in registers • Consider a 1-register stack machine – The register is called the accumulator Alex Aiken Stack Machines • In a pure stack machine – An add does 3 memory operations – Two reads and one write to the stack • In a 1-register stack machine the add does acc acc + top_of_stack Alex Aiken Stack Machines • Consider an expression op(e1,…,en) – Note e1,…,en are subexpressions • For each ei (0 < i < n) – Compute ei – Push result on the stack • Pop n-1 values from the stack, compute op • Store result in the accumulator Alex Aiken Stack Machines Alex Aiken Stack Machines After evaluating an expression e, the accumulator holds the value of e and the stack is unchanged. -

Writable Instruction Set Stack Oriented Computers

Proceedings of the 1987 Rochester Forth Conference 49 WRITABLE INSTRUCTION SET, STACK ORIENTED COMPUTERS: The WISC Concept Philip Koopman Jr. WISC Technologies, Inc. Box 429 Route 2 La Honda, CA 94020 ABSTRACT Conventional computers are optimized for executing programs made up of streams' of serial instructions. Conversely, modern programing practices stress the importance of non-sequential control flow and small procedures. The result of this hardware/software mismatch in today's general purpose computers is a costly, sub optimal, self-perpetuating compromise. The solution to this problem is to change the paradigm for the computing environment. The two central concepts required in this new paradigm are efficient procedure calls and a user-modifiable instruction set. Hardware that is fundamentally based on the concept of modularity will lead to changes in computer languages that will better support efficient software development. Software that is able to customize the hardware to meet critical application-specific processing requirements will be able to attempt more difficult tasks on less expensive hardware. Writable Instruction Set/Stack Oriented Computers (WISC computersr exploit the synergism between multiple hardware stacks and writable microcode memory to yield improved performance for general purpose computing over conventional processors. Specific strengths of a WISC computer are simple hardware, high throughput, zero-cost procedure calls and a machine language to microcode .interface. WISC Technologies' CPU/32 is a 32-bit commercial processor that implements the WISC philosophy. INTRODUCTION People buy computers to solve problems. People measure the success of computers by how much was saved by using a computer to solve their problems. What is the expense of using a computer to solve a problem? Computers cost users not only money for hardware and software, but also resources for training, labor, and waiting for solutions (both during development and during use). -

Stack Machines

What is SaM? • SaM is a simple stack machine designed to introduce you to compilers in 3-4 lectures • SaM I: written by me around 2000 – modeled vaguely after JVM SaM I Am • SaM II: complete reimplementation and major extensions by Ivan Gyurdiev and David Levitan (Cornell undergrads) around 2003 • Course home-page has – SaM jar file – SaM instruction set manual – SaM source code SaM Screen-shot Stack machine • All data is stored in stack (or heap) – no data registers although there might be control registers • Stack also contains addresses • Stack pointer (SP) points to the first free location on stack • In SaM, stack addresses start at 0 and go up • Int/float values take one stack location . …. 102 SP 101 5 100 4 . …... …... 0 1 Program area in SaM Program area Stack machine HALT …….. SaM 2 ……. • Stack machine is sometimes called a 0- 1 PUSHIMM 8 address machine 0 PUSHIMM 7 PC – arithmetic operations take operands from top of • Program area: stack and push result(s) on stack – contains SaM code – one instruction per location • Program Counter (PC): …. – address of instruction to be executed ADD 102 102 SP SP – initialized to 0 when SaM is booted up 101 5 101 100 4 100 9 • HALT: …... …... – Initialized to false (0) when SaM is booted up – Set to true (1) by the STOP command – Program execution terminates when HALT is set to true (1) Program Execution Program area Loader HALT …….. SaM 2 ……. • How do commands get into the Program 1 PUSHIMM 8 area of SaM? 0 PUSHIMM 7 PC • Loader: a program that can open an input Command interpreter: file of SaM commands, and read them into PC = 0; the Program area. -

Instruction Set Evolution in the Sixties: GPR, Stack, and Load-Store Architectures

1 Instruction Set Evolution in the Sixties: GPR, Stack, and Load-Store Architectures Arvind Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory M.I.T. Based on the material prepared by Arvind and Krste Asanovic 6.823 L3- 2 Arvind The Sixties • Hardware costs started dropping - memories beyond 32K words seemed likely - separate I/O processors - large register files • Systems software development became essential -Operating Systems - I/O facilities • Separation of Programming Model from implementation become essential - family of computers September 14, 2005 6.823 L3- 3 Arvind Issues for Architects in the Sixties • Stable base for software development • Support for operating systems – processes, multiple users, I/O • Implementation of high-level languages – recursion, ... • Impact of large memories on instruction size • How to organize the processor state from the programming point of view • Architectures for which fast implementations could be developed September 14, 2005 6.823 L3- 4 Three Different Directions in Arvind the Sixties • A machine with only a high-level language interface – Burrough’s 5000, a stack machine • A family of computers based on a common ISA – IBM 360, a General Register Machine • A pipelined machine with a fast clock (Supercomputer) – CDC 6600, a Load/Store architecture September 14, 2005 6.823 L3- 5 Arvind The Burrough’s B5000: An ALGOL Machine, Robert Barton, 1960 • Machine implementation can be completely hidden if the programmer is provided only a high-level language interface. • Stack machine organization because stacks are convenient for: 1. expression evaluation; 2. subroutine calls, recursion, nested interrupts; 3. accessing variables in block-structured languages. • B6700, a later model, had many more innovative features – tagged data –virtual memory – multiple processors and memories September 14, 2005 6.823 L3- 6 Arvind A Stack Machine Processor A Stack machine has a stack as a part of the processor state stack Main typical operations: Store push, pop, +, *, ..