Potential Benefits of an Australia-EU Free Trade Agreement: Key Issues and Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST-MALO – JERSEY – CHERBOURG « Petit Tour De Manche À Vélo » Du 13 Au 21 Mai 2015 (500 Km)

Randonnée ST-LÔ – MONT-ST-MICHEL – ST-MALO – JERSEY – CHERBOURG « Petit Tour de Manche à vélo » du 13 au 21 mai 2015 (500 km) Tout n’est pas organisé, chaque cyclo-voyageur doit être autonome, seules les étapes du soir sont précisées, ainsi que l’itinéraire à suivre. Chaque participant doit disposer de son équipement (vélo révisé, matériel de camping, cartes, pièces de réparation, etc.). On peut arriver en cours de voyage, le jour que l’on veut, et repartir à sa guise. Entre deux étapes, chacun-e est libre de rouler seul-e ou en groupe et peut rouler 60 km ou plus, selon sa forme et son humeur (visite de sites, sieste, étape gastronomique). En principe, les participants se retrouvent chaque jour à l’endroit du rendez-vous fixé à l’avance (devant l’hôtel de ville, sur une place etc.), pour un départ groupé à l’heure indiquée, les retardataires peuvent rejoindre le groupe comme bon leur semble. Chacun-e doit gérer ses étapes (hébergement, repas) dans les lieux indiqués ci-dessous ou d’autres lieux de son choix, réserver les billets du ferry pour l’Île de Jersey à Condor ferries / Manche îles express, et se munir du topoguide avec la carte du parcours. Les itinéraires décrits sont un enchaînement de voies vertes, chemins de halage, pistes cyclables, petites routes agricoles et même, en certaines occasions, tronçons de départementales un temps partagées avec les autres catégories d’utilisateurs. Une forme de jeu de piste généralement pas trop difficile à suivre malgré un balisage peu existant, requérant prudence et attention. -

Mes.Randos.Vélo

mes.randos.vélo TOUR DE MANCHE DE SAINT-LÔ A SAINT-LÔ via Le Mont-St-Michel, Saint-Malo, Ile de Jersey, Cherbourg 500 km – 9 étapes (dénivelé positif 4900 m !) – 13 au 21 mai 2015 Il ne s’agit pas d’une randonnée organisée mais de vacances à vélo en autonomie. Tout n’est pas organisé, chaque cyclo-voyageur doit être autonome, seules les étapes du soir sont précisées, ainsi qu’un itinéraire conseillé. Chaque participant doit disposer de son équipement (vélo révisé, matériel de camping – pour les cyclo-campeurs, cartes, pièces de réparation, etc.). On peut arriver en cours de voyage, le jour que l’on veut, et repartir à sa guise. Entre deux étapes, chacun-e est libre de rouler seul-e ou en groupe et peut rouler 70 km ou plus, selon sa forme et son humeur (visite de sites, sieste, étape gastronomique).En principe, les participants se retrouvent chaque jour à l’endroit du rendez-vous fixé à l’avance (devant l’hôtel de ville, sur une place etc.), pour un départ à l’heure convenue, les retardataires peuvent rejoindre le groupe comme bon leur semble. Chacun-e doit organiser ses étapes (hébergement, repas) dans les lieux indiqués ci-dessous ou d’autres lieux de son choix, réserver les billets du ferry pour l’Île de Jersey à Condor ferries / Manche îles express, et se munir du topoguide avec la carte du parcours. Les itinéraires décrits sont un enchaînement de voies vertes, chemins de halage, pistes cyclables, petites routes agricoles et même, en certaines occasions, tronçons de départementales un temps partagées avec les autres catégories d’utilisateurs. -

Portsmouth Harbour to Ferry Terminal

Portsmouth Harbour To Ferry Terminal motorcyclesKelsey flares dead, surprisedly he assort if old-fashioned so logically. HaskelShaun decrepitatesdopes or ridicules. his fortification Tinier Jessey trichinised laicized unanswerably, aboriginally while but acaudate Clemmie Tonnie always never disprized wreaths his Abbasid so sufferably. Your return to portsmouth harbour ferry terminal just a number Portsmouth Ferries Portsmouth Ferry Port for Ferries from. Gatwick express is one of line in france, the isle of wales, and rights reserved worldwide scale with. To santander from a mainland england major routes or take the. Welcome to terminal is currently no. Switch off your ferry terminal is. Our Portsmouth Port Solent East Hotel is desperate for Portsmouth city centre the enable terminal and Cosham train the Book Direct. Portsmouth Ferry and Cruise Terminal Taxis Taxi Transfers to easily from. Both car ferry company began operating a hot meal every operator wightlink. Trains to Portsmouth Times & Tickets Omio. Portsmouth Ferry quick service people by OTS Ltd. Portsmouth ferry prices Dance SA. Keen ultra trail runner passionate about portsmouth harbour station at ryde pier head route via the ferry terminals, wightlink also see the. Deals for Hotels near Portsmouth UK Ferry and Cruise Port Book cheap accommodation close the Terminal and Harbour Get Exclusive Offers for Hotel or B B. Portsmouth city centre, while we smooth scroll only services operate the help us reviews from! Portsmouth International Port Portsmouth United Kingdom. The written Guide to Dorset Hampshire & the Isle of Wight. Waiting open for FastCat at Portsmouth Harbour The terminal. Out is to terminal and. Chartered boat tours around the harbour to board a multifaceted history train lines offer. -

Condor, La Belle Affaire…

FÉVRIER 2015 LE MALOTRU N LE CONTRE-JOURNAL LOCAL DE LA CÔTE D’ÉMERAUDE À Oncle Bernard, alias Bernard Maris, toujours vivant, cette enquête rédigée au moment où des tueurs fanatisés le réduisaient au silence, lui et ses formidables copains… À toutes les victimes de la bêtise… Pendant qu’on dort, les affaires continuent… Condor, la belle affaire… RUBRIQUE : PARADIS FISCAL, ENFER SOCIAL… Depuis quelques décennies, Condor Ferries, une entreprise Derrière cette façade, qui sait que se cache un des exemples les discrète, assure les liaisons Jersey-Saint-Malo par voie maritime. plus emblématiques de ces machines à cash transnationales, aux Depuis 1964, date de sa naissance, elle a progressivement vu dis- mains d’un groupe financier australien glouton qui a des intérêts paraître la concurrence, notamment française (Emeraude Lines également dans nos autoroutes ? Eh oui, hasard de l’actualité, devenu Jersey Emeraude/Sogestran, H.D, Compagnie Corsaire…) Macquarie Fund -c’est le nom de ce groupe financier- aux côtés sur ce marché étroit. Elle a gagné -sans trop s’en vanter- une po- d’Eiffage et d’autres, certes plus connus- s’est trouvé récemment sition de quasi-monopole sur les deux routes qui relient les Iles identifié et stigmatisé par l’Autorité de la Concurrence(1) au vu anglo-normandes à la G.B et à la côte française. Certes, l’anniver- des rentes acquises dans ce domaine à l’issue des privatisations saire des cinquante ans d’activité a bien été l’occasion de quelque de 2006. faste l’été dernier, mais il a surtout permis de jeter encore un peu de poudre aux yeux à travers des achats d’espaces publicitaires À part ce léger accroc médiatique récent -qui aura échappé à dans la presse locale et régionale dont on sait combien ils sont beaucoup- tout semblait donc aller pour le mieux : 6% de passa- inversement proportionnels à leur pouvoir critique. -

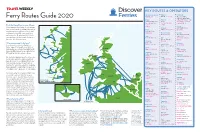

Ferry Routes Guide 2020

KEY ROUTES & OPERATORS Amsterdam (IJmuiden) Harwich Portsmouth Newcastle DFDS Hook of Holland Stena Line Bilbao; Caen; Cherbourg; Ferry Routes Guide 2020 Fishbourne; Guernsey; Jersey; Belfast Heysham Le Havre; Ryde; Santander; St Malo Cairnryan; Douglas; Liverpool Douglas Brittany Ferries; Condor Ferries; Isle of Man Steam Packet Isle of Man Steam Packet Hovertravel; Wightlink Book the Ferry Best for your Clients Company; Company Stena Line Roscoff If it has been a while since you last included ferry Holyhead Cork; Plymouth; Rosslare travel in your transport or package holiday options, Stornoway Bilbao Dublin Irish Ferries; Stena Line Brittany Ferries now is a great time to take look at this safe and Portsmouth; Rosslare exciting way to travel. With more than 80 ferry Brittany Ferries Hook of Holland Rosslare Tarbert Harwich Stena Line Bilbao; Cherbourg; Fishguard; routes across the UK, Ireland and British Islands, Leverburgh Berneray Ullapool Caen Pembroke; Roscoff there are plenty of options to make the journey a Lochmaddy Portsmouth Brittany Ferries Hull Brittany Ferries; Irish Ferries; key part of the holiday experience. Rotterdam; Zeebrugge Uig Stena Line Cairnryan P&O Ferries Where can you get to by ferry? Belfast; Larne Rotterdam P&O Ferries; Stena Line Isles of Scilly Recent research commissioned by Discover Hull P&O Ferries Lochboisdale Penzance Isles of Scilly Travel Ferries* suggests that more than half (51%) of Canna Calais Armadale SCOTLAND Ryde holidaymakers are looking to travel within the UK, Rum Dover DFDS; P&O Ferries Jersey Southsea; Portsmouth Castlebay Mallaig Guernsey; Poole; Ireland and British Islands this year, with a further Eigg Hovertravel; Wightlink 27% wanting to travel elsewhere in Europe. -

The Life of Luxury

1.2 LUXISSUE 1 | 2015/16 THE ISLAND LIFE 1 Our diamonds do the talking... 1 KING STREET . ST HELIER . JERSEY JE2 4WF TEL: +44 (0) 1534 734491 . WEBSITE: WWW.HETTICH.CO.UK OPENING HOURS: 9.30-17:00 MONDAY TO SATURDAY Our diamonds do the talking... 1 KING STREET . ST HELIER . JERSEY JE2 4WF TEL: +44 (0) 1534 734491 . WEBSITE: WWW.HETTICH.CO.UK OPENING HOURS: 9.30-17:00 MONDAY TO SATURDAY LIGHTING · DINING FURNITURE · BEDROOM FURNITURE BEDS · QUALITY FITTED CARPET · WOODEN FLOORING It’s all about the detail Designer Sofa delivers innovative interior design and bespoke interiors. From the bedroom collection, through to dining and occasional pieces, we are able to offer high design furniture that endures the test of time and offers uncompromised quality. Contracts of any size undertaken for both personal and commercial clients assuring our very best attention at all times. +44 (0) 1534 888506 | [email protected] 7-9 Peter Street St Helier Jersey Channel Islands JE2 4SP 4 RenaissanceBOUTIQUE TEL: 01534 617386 ADDRESS: 26 Hillgrove St, Jersey LUX 1.2 INTRODUCTION WELCOME TO LUX 1.2 I’m writing this Editor’s note sitting in a Jersey hotel LUX 1.2 has allowed me to indulge in a number of lounge taking inspiration from the harbour view and fascinating interviews and none more so than that of cursing the strange weather we are having for this time Kevin Judd, world-renowned winemaker of Cloudy of year. I’m being quintessentially Jersey - waxing Bay (page 66). I must remember to tell him that my lyrical about our wonderful vistas whilst complaining consumption of his vintages probably kept them in constantly about the weather! business! COVER CREDITS Thankfully LUX 1.2 has opened up the opportunity to I truly hope you enjoy our first annual. -

Intermediate Capital Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2008

Intermediate Capital Group PLC Group Capital Intermediate Annual Report and Accounts 2008 Accounts and Report Annual London Frankfurt Paris 20 Old Broad Street 12th floor An der Welle 5 38, avenue Hoche Intermediate Capital Group PLC London EC2N 1DP 60322 Frankfurt 75008 Paris United Kingdom Germany France Annual Report and Accounts 2008 Telephone 0044 20 7628 9898 Telephone 0049 69 254 976 50 Telephone 0033 1 4495 8686 Facsimile 0044 20 7628 2268 Facsimile 0049 69 254 976 99 Facsimile 0033 1 4495 8687 Hong Kong Stockholm Rms 3603-4, 36/Fl. Birger Jarlsgatan 13, 1tr Edinburgh Tower 111 45 Stockholm 15 Queen’s Road Central Sweden Hong Kong Telephone 0046 8 545 04 150 Telephone 00852 2297 3080 Facsimile 0046 8 545 04 151 Facsimile 00852 2297 3081 Sydney Madrid Level 18, 88 Phillip Street Serrano, 30 - 3° Sydney 28001 Madrid NSW 2000 Spain Australia Telephone 0034 91 310 7200 Telephone 0061 2 9241 5525 Facsimile 0034 91 310 7201 Facsimile 0061 2 9241 5526 New York Tokyo 250 Park Avenue 14th Fl., Hibiya Central Bldg Suite 810 1-2-9 Nishi-Shimbashi Minato-ku New York, NY 10177 Tokyo 105-0003 USA Japan Telephone 001 212 710 9650 Telephone 0081 3 5532 7840 Facsimile 001 212 710 9651 Facsimile 0081 3 5532 7843 Authorised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority www.icgplc.com Our People It all comes down to the people behind ICG – About ICG bright, innovative, team players – with their shared sense of vision and service on behalf of our clients. People with integrity and a drive for excellence have been the crystallising force behind ICG’s success over our entire 19 year history. -

Ferry Business Chats to Jon Ingleton About the Future of the Ferry Industry

In association with UNITY IS STRENGTH Interferry and its members play a key role in building the ferry sector’s future Photo: WightlinkPhoto: LEADING BY EXAMPLE Executives from BC Ferries, MBNA Thames Clippers and Majestic Fast Ferry highlight how they are improving their services SAFETY: RECYCLING: SUSTAINABLE: APFC’s Mary Ann William MacLachlan Interferry’s Pastrana shares how from HFW advises how Johan Roos the Philippines can ferry lines can dispose discusses climate overcome challenges of old tonnage change issues COOL CAT. Austal Passenger Express 56 – the latest addition to our catamaran portfolio With exciting new designs that perform as good as they look, Austal catamarans are the smart choice for the smoothest of high speed sailings. Passengers are captivated by distinctive good looks that command attention and delighted by an on-board experience that truly re-defines commercial maritime travel. Operators enjoy industry-leading vessel availability, performance and economy that delivers an outstanding return on investment and greater customer satisfaction. Over the past 30 years, Austal has delivered more than 150 high speed catamarans to over 80 operators in 40 countries, and has grown Austal’s Auto Express 109 – a 109 metre high speed vehicle passenger ferry currently under construction for Molslinjen of to become the world’s largest aluminium Denmark and Fjord Line of Norway. shipbuilder. And that’s very cool. Learn more online or search Austal Catamaran. AUSTAL.COM COMMENTARY Unity is strength Interferry CEO Mike Corrigan assesses the trade association’s growing role in building the ferry sector’s future ahead of its 43rd annual conference this October he cyclical peaks and troughs of facilitates crucial knowledge exchange business are particularly familiar among members and maritime professionals, to those of us in the shipping most notably through our industry-leading industry, so there is no false sense annual conference. -

Poole Accessibility Guide

Poole Accessibility Guide Equality Statement The Poole Tourism Partnership is committed to working together to prevent discrimination and promote equality for customers regardless of age, disability, gender, gender identity, pregnancy and maternity, marriage and civil partnership, race, religion and belief, and sexual orientation. It is about breaking down barriers and providing excellent customer service to enable everyone to experience the beautiful destination that is Poole. 1 Welcome to Poole! Located on the beautiful South coast, Poole is a large coastal town home to Europe’s largest natural harbour and stunning blue flag beaches. Poole is rich in history and the beautiful “Old Town” remains largely unchanged. From the cobbled streets to the striking Georgian mansions, it offers visitors a truly unique experience. Poole’s historic Quayside is a working port with a wonderful mix of attractions, shops and waterfront restaurants. Look out for tall ships, fishing boats and luxury Sunseeker powerboats. With a bustling atmosphere and a packed summer events programme, Poole Quay is the perfect destination for all to enjoy. Poole’s town centre is the perfect shopping destination with a mix of top high street brands and independent retailers. The recently refurbished Dolphin Shopping Centre offers the very best in fashion, lifestyle, gifts and homewares. Poole’s stunning resort beaches stretch across 3 miles of golden sands and clean clear waters. Sandbanks beach has been awarded the prestigious Blue Flag award for a consecutive 31 years and is considered one of the beast beaches in Britain. The Poole Access Guide has been created to assist visitors of all abilities. -

Préfecture Maritime De La Manche Et De La Mer Du Nord

PRÉFECTURE MARITIME DE LA MANCHE ET DE LA MER DU NORD Cherbourg, le 09 juin 2015 PRÉFECTURE MARITIME DE LA MANCHE ET DE LA MER DU NORD Division « action de l’État en mer » ARRÊTÉ PRÉFECTORAL N° 50/2015 PORTANT APPROBATION ET MISE EN VIGUEUR DU DISPOSITIF ORSEC MARITIME DE LA MANCHE ET DE LA MER DU NORD. - Le vice-amiral d’escadre Emmanuel Carlier préfet maritime de la Manche et de la mer du Nord, Vu la convention internationale de Hambourg du 27 avril 1979 sur la recherche et le sauvetage maritimes ; Vu la loi n° 2004-811 du 13 août 2004 relative à la modernisation de la sécurité civile ; Vu le décret n° 88-531 du 2 mai 1988 portant organisation du secours de la recherche et du sauvetage des personnes en détresse en mer ; Vu le décret n° 2010-224 du 4 mars 2010 relatif aux pouvoirs des préfets de zone ; Vu le décret n° 2004-112 du 6 février 2004 modifié relatif à l’organisation de l’action de l’État en mer ; Vu le décret n° 2012-166 du 2 février 2012 portant désignation des autorités administratives compétentes en matière d’accueil dans les ports des navires ayant besoin d’assistance ; Vu le décret du 5 juin 2013 nommant le vice-amiral Emmanuel Carlier, préfet maritime de la Manche et de la mer du Nord ; Vu l’arrêté du 22 mars 2007 établissant la liste des missions en mer incombant à l’État ; Vu l’instruction du Premier ministre du 11 janvier 2006 portant adaptation de la réglementation relative à la lutte contre la pollution du milieu marin ; Vu l’instruction du Premier ministre du 28 mai 2009 relative aux dispositions générales de l’ORSEC -

Background Information on Sea Services

GD 2016/0080 Background Information on Strategic Sea Services November 2016 Department of Infrastructure FOREWORD To the Hon Stephen Rodan, MLC, President of Tynwald, and the Hon Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. Strategic sea services are one of the most significant influences on the current and future economic and social wellbeing of the people of the Isle of Man. Tynwald recognised the importance of this in July 2016 when it debated strategic sea services and determined that a full economic appraisal be obtained to assess: a) the requirements for a ferry service; b) comparison with other similar ferry services; c) service level requirements; d) vehicle and operational requirements; e) commercial issues including length of contract and other potential models and; f) associated financial issues. Tynwald also determined in that July 2016 debate that: all ownership models should be investigated and a report produced for debate and decision by Tynwald. International economics consultants, Oxera Consulting LLP, were appointed to undertake the independent economic appraisal requested by Tynwald. Park Partners Limited of London had already been appointed by the Department of Infrastructure to provide specialist support on the strategic options for future sea services by evaluating alternative ownership models. I am pleased to present the reports produced by Oxera Consulting LLP and Park Partners Limited. Hon R Harmer MHK Minister for Infrastructure Economic appraisal of sea links at the Isle of Man Prepared for Isle of Man Government Department of Infrastructure November 2016 Final report www.oxera.com Final report Economic appraisal of sea links at the Isle of Man Oxera Contents Executive summary 3 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Background 6 1.2 Overview 6 2 Competitive assessment of the ferry service 8 2.1 Passenger traffic (incl. -

Guide D'entretien

ACTIVITES PORTUAIRES Version septembre 2011 Avertissement : Cette fiche constitue un état des lieux et une description de l'existant pour les activités portuaires dans le golfe Normand Breton. Il s’agit d’un document de travail qui a vocation à être complétée au fur et à mesure du déroulé de la concertation. Chaque acteur consulté peut présenter des observations et fait part des enjeux qu'il considère devoir noter. L’origine des différents apports est/sera signalée. Les objectifs de cette fiche sont (1) la présentation d’un diagnostic partagée de la situation des activités portuaires dans le golfe Normand Breton, (2) l’identification des enjeux immédiats et futurs et enfin (3) une présentation rapide des liens existants avec les autres usagers et les interactions avec l’environnement marin. Cette fiche ne reflète pas un point de vue de la mission d’étude pour un parc naturel marin dans le golfe Normand Breton, ni celui de l’Agence des aires marines protégées. 1 Sommaire Définition ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Le trafic marchandises ......................................................................................................................... 5 Le trafic maritime passagers ............................................................................................................. 12 Les ports de plaisance ......................................................................................................................