In Hub Gearbox Front Wheel Drive Cycles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516 Phone: 518-329-1142 December 1, 2012 Pedaling History Bicycle Museum Auction 12/1/2012 LOT # LOT # 1 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed 6 Royal Doulton Pitcher and Tumbler 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed. Site, 81" x 41". English Doulton Lambeth Pitcher 161, and "Niagara Lith. Co. Buffalo, NY 1898". Superb Royal-Doulton tumbler 1957. Estimate: 75.00 - condition, probably the best known example. 125.00 Estimate: 3,000.00 - 5,000.00 7 League Shaft Drive Chainless Bicycle 2 46" Springfield Roadster High Wheel Safety Bicycle C. 1895 League, first commercial chainless, C. 1889 46" Springfield Roadster high wheel rideable, very rare, replaced headbadge, grips safety. Rare, serial #2054, restored, rideable. and spokes. Estimate: 3,200.00 - 3,700.00 Estimate: 4,500.00 - 5,000.00 8 Wood Brothers Boneshaker Bicycle 3 50" Victor High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. 1869 Wood Brothers boneshaker, 596 C. 1888 50" Victor "Junior" high wheel, serial Broadway, NYC, acorn pedals, good rideable, #119, restored, rideable. Estimate: 1,600.00 - 37" x 31" diameter wheels. Estimate: 3,000.00 - 1,800.00 4,000.00 4 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle 9 Elliott Hickory Hard Tire Safety Bicycle C. 1886 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel C. 1891 Elliott Hickory model B. Restored and "Challenge", older restoration, incorrect step. rideable, 32" x 26" diameter wheels. Estimate: Estimate: 1,700.00 - 1,900.00 2,800.00 - 3,300.00 4a Gormully & Jeffery High Wheel Safety Bicycle 10 Columbia High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. -

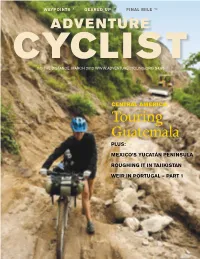

Adventure Cyclist and Dis- Counts on Adventure Cycling Maps

WNTAYPOI S 8 GEARED UP 40 FINAL MILE 52 A DVENTURE C YCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. MARCH 2012 WWW.ADVentURECYCLING.ORG $4.95 CENTRAL AMERICA: Touring Guatemala PLUS: MEXIco’S YUCATÁN PENINSULA ROUGHING IT IN TAJIKISTAN WEIR IN PORTUGAL – PART 1 3:2012 contents March 2012 · Volume 39 Number 2 · www.adventurecycling.org A DVENTURE C YCLIST is published nine times each year by the Adventure Cycling Association, a nonprofit service organization for recreational bicyclists. Individual membership costs $40 yearly to U.S. addresses and includes a subscrip- tion to Adventure Cyclist and dis- counts on Adventure Cycling maps. The entire contents of Adventure Cyclist are copyrighted by Adventure Cyclist and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from Adventure Cyclist. All rights reserved. OUR COVER Cara Coolbaugh encounters a missing piece of road in Guatemala. Photo by T Cass Gilbert. R E LB (left) Local Guatemalans are sur- GI prised to see a female traveling by CASS bike in their country. MISSION CYCLE THE MAYAN KINGDOM ... BEFORE IT’s TOO LATE by Cara Coolbaugh The mission of Adventure Cycling 10 Guatemela will test the mettle of both you and your gear. But it’s well worth the effort. Association is to inspire people of all ages to travel by bicycle. We help cyclists explore the landscapes and THE WONDROUS YUCATÁN by Charles Lynch history of America for fitness, fun, 20 Contrary to the fear others perceived, an American finds a hidden gem for bike touring. and self-discovery. CAMPAIGNS TAJIKISTAN IS FOR CYCLISTS by Rose Moore Our strategic plan includes three 26 If it’s rugged, spectacular bike travel that you seek, look no further than Central Asia. -

Bianchi Zurigo Disc 10

SPECIFICATIONS 9. Wheelbase: 1020mm Road Test BIANCHI ZURIGO DISC 10. Standover height: 810mm 11. Frame: 7000 series Price: $1,799 aluminum, triple-butted, Sizes available: 49cm, 52cm, hydroformed tubes; tapered 55cm, 58cm, 61cm head tube; top tube flattened Sizes tested: 55cm underneath for carrying. Bosses for two water bottle Weight: 23.3 lbs. (55cm, with cages; mounts for fender and Shimano XT M770 pedals) rear rack; disc brake mounts; cable stops; internally routed TEST BIKE MEASUREMENTS rear brake cable; chain keeper; 1. Seat tube: 55cm (center to replaceable derailer hanger top) 12.Fork: Carbon with alloy 2. Top tube: 55cm steerer (1 1/8 to 1 1/2 in.); 3. Head tube angle: 72° fender mounts at fork crown and dropouts; disc mounts 4. Seat tube angle: 74° 13. Rims: Bianchi Reparto Corse 5. Chainstays: 430mm by Maddux SR300, 32mm 6. Bottom bracket drop: 65mm deep section, 32-hole BIANCHI ZURIGO DISC 7. Crank spindle height above 14. Spokes: straight gauge, 14g, ground: 295mm anodized black and white 8. Fork offset: 48mm BY PATRICK O’GRADY ➺“THIS IS A COOL-LOOKING one!” exclaimed the grinning mechanic as I picked up a Bianchi Zurigo Disc for an Adventure Cyclist test ride. He wasn’t kidding. The guys at Old Town Bike Shop in Colorado Springs have built up a lot of bikes for me over the years, most of them fairly utilitarian, loaded touring machines, the pickup trucks of the cycling world. Many have had a certain je ne sais quoi, and a few have been downright handsome. But “cool?” That’s not a word that leaps to mind when you’re evaluating the dubious charms of an Ford F-150. -

Making a Pedal Pitch - Possible Research Topics the Following Are Some Ideas for Guiding a Brainstorming Session

Intel® Teach Program Designing Effective Projects Making a Pedal Pitch - Possible Research Topics The following are some ideas for guiding a brainstorming session. Numbering corresponds to exercise numbers. 1. Wheel diameter: Is it possible to fill front panniers so full that the bags limit the turning radius of the bicycle? What is the turning radius needed for streets that intersect at various angles? Does the size of the wheel affect the turning radius (compare a BMX bicycle with a mountain bicycle)? Is there a relationship between wheel diameter and coasting distance? 2. Banking of race courses: Calculate the speeds for which a particular bicycle racecourse or velodrome is designed. 3. Reading and making graphs: Create a time and distance graph to describe a summer biathlon competition (cross-country cycling and marksmanship). Create a time and distance graph to describe an Ironman Triathlon (running, swimming, cycling) 4. Bicycle falling over: Has a bicycle or tricycle falling over been used in comedy? Do they fall over at fast or slow speeds? Why are bicycle helmets needed? Who wears them … in your community, in your state, nationally? For a child, teen, or adult, what is the sitting height on a typical tricycle or bicycle for each age group (hot wheels, small bicycle, BMX, trail bicycle, touring bicycle, racing bicycle, an old fashioned bicycle with large front wheel and small back wheel, unicycle)? What are safe ways to transport a child using a bicycle? Is a child safer seated behind the rider, in front of the rider (using a specialized seat and pedals), in a towed cart? See http://www.burley.com/. -

VELO-TOURING Email: [email protected] Special Tour Operator-Since 1991 Web

H-1118 Budapest, Előpatak u.1. Tel.: + 36-1-319-0571 VELO-TOURING Email: [email protected] Special Tour Operator-Since 1991 Web: www.velotouring.eu www.velo-touring.hu Bike Tour No. 14 Lake Balaton Round Trip The great Balaton Bicycle Trail – all around the Lake Arriving and Departure in Budapest - Independent, by service van supported, self-guided tour with luggage transport – Duration: 7 days / 6 nights Cycling Distance: ca. 215-229 km/135-144 miles, from it 30-52 km / 19-33 miles per day (Daily 4 - 6 hours cycle - by moderated speed) Level of difficulty: You ride a bicycle mainly on the wonderful Lake Balaton cycle trail (signposted) around the "Hungarian Sea", several times on excellent cycle path. The stage is easy, only the North and East shore of the “Hungarian See” has a few hillside routes. But the south and the west shore is completely flat. This tour is well recommend for every cyclist with average experience and suitable for families and seniors. An easy bicycle-aficionado-tour for everyone. (Level 1 - easy) Level of support: Information about the Follower-Van (the Technical Service) - The Driver of the van, however, is not just a chauffeur & luggage supplier! The Follower-Van carries your luggage from hotel to hotel and brings some spare-bikes too. For even more safety along the way is the Driver of the van equipped with mobile (cell-) phones. The daily biking routes cross again and again the way of the Follower-Van. The van follows the cyclists without coming in sight or disturbing. -

VELO-TOURING Spa Tour

H-1118 Budapest, Előpatak u.1. Tel.: + 36-1-319-0571 VELO-TOURING Email: [email protected] Special Tour Operator-Since 1991 www.velo-touring.hu www.velotouring.eu Bicycle Tour No. 12 Spa Tour - with wine region Tokaj From Tokaj along the River Tisza, Through the Puszta to Budapest Wine & Spa Bike Tour – Independent, by service van supported, self-guided tour with luggage transport – Duration: 8 days / 7 nights Cycling Distance: Total 230kms / 144miles, approx. 15-54kms / 9-34 miles/day (Daily cycling about 4 - 6 hours - by moderated speed) Level of difficulty: During this tour you will cycle only through Puszta-regions as flat as a table. Definite easy cycling on flat terrain and several times on paved bike paths of the River Tisza flood protection dam. Quiet roads, mostly with low traffic, a few times excellent cycle path network. An easy tour for everyone who appreciates comfort and spa pleasures. (Level 1 - easy) Level of support: Information about the service and luggage van (the “Technical Service”) - The Driver of the back-up van, however, is not just a chauffeur & luggage supplier! The Follower-Van carries your luggage from hotel to hotel and brings some spare-bikes too. For even more safety along the way is the driver of the van equipped with mobile (cell-) phones. The daily biking routes cross again and again the way of the service and luggage van. The van follows the cyclists without coming in sight or disturbing. It has the tools, spare parts and a travel pharmacy, additional bike bags on board. -

BMW BIKES. Update 2021 DESIGN PHILOSOPHY

BMW BIKES. Update 2021 DESIGN PHILOSOPHY. Special themes of the collection: BMW collaboration with 3T. The collaboration with the Italian brand 3T sets standards. The gravel bike stands out thanks to its precise, minimalist design and state-of-the-art racing components. Clear lines and contours as well as the modern colouring make this bike unique. The BMW M Bike. The material mix of aluminium and carbon analogous to the BMW M vehicles gives this bike its sportiness. Due to the carbon fork specially developed for the bike, the weight of the bike could be reduced by a kilogram. The BMW E-Bikes. Stylish, clear form meets high tech: The BMW Active Hybrid E-Bike and the BMW Urban Hybrid E-Bike feature powerful drive units that blend seamlessly into the slim frame. Both E-Bikes are equipped with an innovative LED battery-charge indicator. DESIGN AND FUNCTION. What we know from BMW vehicles can also be found in BMW Bikes. The BMW Cruise Bikes. They enthuse riders not only with pure driving pleasure, but also with The unmistakable design inspired by the first-class design and innovative functionalities. the fixie trend and the high-quality The modern colour scheme, the linear frame shape with discreet components of the BMW Cruise Bike create BMW branding give the BMW Bikes an unmistakable urban look. The the unique BMW experience even when collaboration with 3T perfects the combination of unique design and biking. innovative components. PRODUCT INFORMATION BMW LIFESTYLE COLLECTIONS 2021. 3 BMW BIKES. 3T FOR BMW GRAVELBIKE The Gravelbike as an exclusive edition for BMW, created in collaboration with the traditional Italian company 3T. -

Bike Tires Road

2010 english BIKE TIRES ROAD. MTB. TOUR Race 4-9 MTB 12-21 Spikes 28-29 Cross 10 -11 Gravity 22-27 Tour 30-37 ThE BRAND ThE NAME Europe’s leading bicycle tire brand, based in Schwalbe is the German word for swallow and Germany. Products: Only bicycle tires. this small bird is a symbol of good fortune in Production: Only in the Schwalbe factory in Korea. For us it symbolizes that cycling is a Indonesia. Distribution: Only through the great form of personal transport: Fast, easy, specialist trade. Since 1973 a successful natural, friendly and free. German-Korean partnership with only one goal: To make the best bicycle tires in the world! SCHWALBE – Only bicycle tires. 2 Balloon 38-39 Wheelchair 44-45 Accessories 50-51 Active 40-43 Tubes 46-49 Information 52-55 PRODUCT LINES EVOLUTION PERFORMANCE ACTIVE The best possible. Excellent quality for intensive Reliable brand quality. Highest quality materials. use. New: All ACTIVE tires have The latest technology. a 50 EPI carcass. Only Schwalbe provides such a high quality tire in this price range. 3 ROAD RACE NEW ULTREMO R Update R.1, HS 380, Evolution Line, Folding tire ETRTO SIZE ! Bar Psi EPI Art.-No. 26” 23-571 650 x 23C High Density Triple Nano Black-Skin 6,0-10,0 85-145 170 g 6 oz 127 11635831 28” 23-622 700 x 23C High Density Triple Nano Black-Skin 6,0-10,0 85-145 180 g 6 oz 127 11646841 High Density Triple Nano White 6,0-10,0 85-145 180 g 6 oz 127 11646848 High Density Triple Nano Silver 6,0-10,0 85-145 180 g 6 oz 127 11646851 High Density Triple Nano Yellow 6,0-10,0 85-145 180 g 6 oz -

Shooting Star: a Biography of a Bicycle

SHOOTING STAR: A BIOGRAPHY OF A BICYCLE Geoff Mentzer 2 SHOOTING STAR: A BIOGRAPHY OF A BICYCLE Copyright © 2020 by Geoff Mentzer All rights reserved. 3 In a scientific study of various living species and machines, the most efficient at locomotion – that is, the least amount of energy expended to move a kilometre – was found to be a man on a bicycle. –SS Wilson, Scientific American, March 1973, Volume 228, Issue 3, 90 The Dandy Horse of 1818, said to be the first velocipede man-motor carriage. Sharp, Bicycles & Tricycles: An Elementary Treatise On Their Design And Construction, Longmans, Green, and Co, London, New York and Bombay, 1896, 147 4 INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What began as a brief biograph of the author's forebear Walter William Curties soon doubled into a study of two men, and expanded into an account of early bicycle – and a little motoring – history in New Zealand. Curties is mostly invisible to history, while Frederick Nelson Adams – who rose to national pre-eminence in motoring circles – by his reticence and reluctance for public exposure is also largely overlooked. Pioneering New Zealand cycling and motoring history – commercial, industrial and social – have been variously covered elsewhere, in cursory to comprehensive chronicles. Sadly, factual errors that persist are proof of copy and paste research. As examples, neither Nicky Oates nor Frederick Adams' brother Harry was the first person convicted in New Zealand for a motoring offence, nor was the world's first bicycle brass band formed in New Zealand. It must be said, however, that today we have one great advantage, ie Papers Past, that progeny of the Turnbull Library in Wellington. -

23Rd Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction

CATALOG PRICE $4.00 Michael E. Fallon / Seth E. Fallon COPAKE AUCTION INC. 266 Rt. 7A - Box H, Copake, N.Y. 12516 PHONE (518) 329-1142 FAX (518) 329-3369 Email: [email protected] Website: www.copakeauction.com 23rd Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction Featuring the David Metz Collection Also to include a selection of ephemera from the Pedaling History Museum, a Large collection of Bicycle Lamps from the Midwest and other quality bicycles, toys, accessories, books, medals, art and more! ************************************************** Auction: Saturday April 12, 2014 @ 9:00 am Swap Meet: Friday April 11th (dawn ‘til dusk) Preview: Thur. – Fri. April 10-11: 11-5pm, Sat. April 12, 8-9am TERMS: Everything sold “as is”. No condition reports in descriptions. Bidder must look over every lot to determine condition and authenticity. Cash or Travelers Checks - MasterCard, Visa and Discover Accepted First time buyers cannot pay by check without a bank letter of credit 17% buyer's premium (2% discount for Cash or Check) 20% buyer's premium for LIVE AUCTIONEERS Accepting Quality Consignments for All Upcoming Sales National Auctioneers Association - NYS Auctioneers Association CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Some of the lots in this sale are offered subject to a reserve. This reserve is a confidential minimum price agreed upon by the consignor & COPAKE AUCTION below which the lot will not be sold. In any event when a lot is subject to a reserve, the auctioneer may reject any bid not adequate to the value of the lot. 2. All items are sold "as is" and neither the auctioneer nor the consignor makes any warranties or representations of any kind with respect to the items, and in no event shall they be responsible for the correctness of the catalogue or other description of the physical condition, size, quality, rarity, importance, medium, provenance, period, source, origin or historical relevance of the items and no statement anywhere, whether oral or written, shall be deemed such a warranty or representation. -

FABRICATION and DEVELOPMENT of CHAINLESS BI-CYCLE Dr.Raghavendra Joshi1,Mayur.D.Pawar2, Shahid Ali3, Mohammed Bilal.K4, Rizwan5,V Muneer Ahmed6

JASC: Journal of Applied Science and Computations ISSN NO: 1076-5131 FABRICATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF CHAINLESS BI-CYCLE Dr.Raghavendra Joshi1,Mayur.D.Pawar2, Shahid ali3, Mohammed bilal.k4, Rizwan5,V Muneer Ahmed6 Professor, mechanical engineering department, BITM, Ballari-583104, Karnataka Assistant professor, mechanical engineering department,BITM, Ballari-583104, Karnataka UG student, mechanical engineering department,BITM, Ballari-583104,Karnataka UG student, mechanical engineering department,BITM, Ballari-583104,Karnataka UG student, mechanical engineering department,BITM, Ballari-583104,Karnataka UG student, mechanical engineering department,BITM, Ballari-583104,Karnataka [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— This project is developed from the users to rotate the back wheel of bi-cycle using propeller shaft. Power transmission through chain drive is the oldest and widest method in case of bi-cycle . In this paper we implemented the chainless transmission to the bicycle to overcome the various disadvantages of chain drive. Shaft drive were introduced over a century ago , but were mostly supplanted by chain driven bi-cycle . Usually in bicycle chain and sprocket is used to drive the back wheel. The shaft drive only need periodic lubrication using grease gun to keep the gears running quite and smooth. A shaft driven bi-cycle is a bi-cycle that uses a shaft drive instead of a join which consist two sprockets with bearings at the both end of shaft connected to pedal crank and rear wheel gear to make a new kind of transmission system for bi-cycle for getting high reliability system, and more safe system. -

Miyata Catalogue 85

MIYATA THERIGHI' E OF REFERENCE rHE RIGHr APPROACH fHE RIGHr sruw The first mistake you can make when buying a Metallurgy is not alchemy but if Miyata tech bicycle, is buying a bicycle. Quite understand nicians have failed to create gold from base met ably You have an end-use in mind so it seems als, they have succeeded with something nearly reasonable to insp ect an end product. And yet, as valuable . Chrome molybdenum alloyed steel. It the collage of components you see has little to do is milled into exc eedingly lightweight, amazingly with what you get. The right frame of reference is strong tubing. Miyata tubing. We call it Cr-Mo. We looking for the right frame. are the only bicycle manufacturer that processes its own tubing, and , as such , we do not have to settle for merely double butted tubes. We have rHE RIGHr OESIGN advanced to triple, even quadruple, butting. It begins with geometry: the relationships be Butting simply means making the tubes tween the major tubes that comprise the frame. thicker on the ends-where they butt together Tube lengths and the angle at which they intersect than they are in the middle. It makes the tube determine how well suited the frame is for a specif stronger where the frame is potentially weaker. ic task. For example: a racing frame's seat and However, not every joint head tubes are more vertical than other frames. re Ce i Ve s th e s am e ____ STRENGTH RETENTIO The top tube is _shorter, and so is the overall wheel stress, so every joint ! base.