Wildlife Biological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propagating California Wild Grape

Ratings of rooting systems (left) were best, good, and fair. Almost all types of vine wood yielded good root systems and resulted in vigorous plants. Propagating California wild grape James A. Robbins 0 David W. Burger Easy to start from cuttings, the vine is useful in landscape plantings California native plants are being used fluenced by such factors as date of collec- ing at that time, sap was flowing freely in increasingly in landscape and revegeta- tion, storage conditions, and type of cane the stems. The segments were transport- tion projects, but little information is wood. We conducted a study to investigate ed to Davis in an ice chest and stored in a available on how to propagate them. Cali- the effect of chemical pretreatment, cold room at 43°F (6°C) for three days. fornia wild grape, Vitis californica wood type, and rooting medium on the Before preparing and treating the cut- Benth., is one such plant that would be rooting of dormant hardwood cuttings of tings, we graded the stem wood into seven useful in the revegetation of steep slopes the California wild grape. classes according to stem diameter, stem and embankments. This vigorous, decidu- length, and type of wood (table 1). Al- ous, woody vine, which grows along though this grouping is artificial, these streams throughout the Coast Ranges, Rooting study categories correlated well with the posi- Central Valley, and Sierra Nevada foot- We collected propagation material in tion of wood on the original canes. Thin- hills, can cover large areas in a short mid-March 1985 from wild vines growing nest wood (grade A) would be associated time. -

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

BOTANICAL FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit

BOTANICAL FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit Project: Burke Creek Highway 50 Crossing and Realignment Project FACTS ID: Location: portions of SEC 22 and SEC 23 T13 N R18 E UTM: Survey Dates:5/13/, 6/25, 8/12/2015 Surveyor/s: Jacquelyn Picciani for Wood Rodgers Directions to Site: Access to the west portion of Burke Creek is gained by turning west on Kahle Drive, and parking in the defined parking lot. Access to the east portion of Burke Creek is gained by turning east on Kahle Drive and parking to the north in the adjacent commercial development parking area. USGS Quad Name: South Lake Tahoe Survey type: General and Intuitive Controlled Describe survey route taken: Survey area includes all road shoulders and right –of –way within the proposed project boundaries, a commercial development on east side of US Highway 50 just north of Kahle Drive, and portions of the Burke Creek/Rabe Meadows complex (Figure 1). Project description: The project area includes open space administered by Nevada Tahoe Conservation District and the USFS, and commercial development, with the majority of the project area sloping west to Lake Tahoe. The Nevada Tahoe Conservation District is partnering with USFS, Nevada Department of Transportation (NDOT), Douglas County and the Nevada Division of State Lands to implement the Burke Creek Highway 50 Crossing and Realignment Project (Project). The project area spans from Jennings Pond in Rabe Meadow to the eastern boundary of the Sierra Colina Development in Lake Village. Burke Creek flows through five property ownerships in the project area including the USFS, private (Sierra Colina and 801 Apartments LLC), Douglas County and NDOT. -

A Note on Host Diversity of Criconemaspp

280 Pantnagar Journal of Research [Vol. 17(3), September-December, 2019] Short Communication A note on host diversity of Criconema spp. Y.S. RATHORE ICAR- Indian Institute of Pulses Research, Kanpur- 208 024 (U.P.) Key words: Criconema, host diversity, host range, Nematode Nematode species of the genus Criconema (Tylenchida: showed preference over monocots. Superrosids and Criconemitidae) are widely distributed and parasitize Superasterids were represented by a few host plants only. many plant species from very primitive orders to However, Magnoliids and Gymnosperms substantially advanced ones. They are migratory ectoparasites and feed contributed in the host range of this nematode species. on root tips or along more mature roots. Reports like Though Rosids revealed greater preference over Asterids, Rathore and Ali (2014) and Rathore (2017) reveal that the percent host families and orders were similar in number most nematode species prefer feeding on plants of certain as reflected by similar SAI values. The SAI value was taxonomic group (s). In the present study an attempt has slightly higher for monocots that indicate stronger affinity. been made to precisely trace the host plant affinity of The same was higher for gymnosperms (0.467) in twenty-five Criconema species feeding on diverse plant comparison to Magnolids (0.413) (Table 1). species. Host species of various Criconema species Perusal of taxonomic position of host species in Table 2 reported by Nemaplex (2018) and others in literature were revealed that 68 % of Criconema spp. were monophagous aligned with families and orders following the modern and strictly fed on one host species. Of these, 20 % from system of classification, i.e., APG IV system (2016). -

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids Lawrence M. Hanks University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, Illinois Qiao Wang Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 133 4.2 Phenology of Adults ..................................................................................................................... 134 4.3 Diet of Adults ............................................................................................................................... 138 4.4 Location of Host Plants and Mates .............................................................................................. 138 4.5 Recognition of Mates ................................................................................................................... 140 4.6 Copulation .................................................................................................................................... 141 4.7 Larval Host Plants, Oviposition Behavior, and Larval Development .......................................... 142 4.8 Mating Strategy ............................................................................................................................ 144 4.9 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 148 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. -

December 1977 MIKES Umarr

n 30 X University of Nevada Reno Correlation of Selected Nevada Lignite Deposits by Pollen Analysis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Serenes ty David A. Orsen Ul December 1977 MIKES UMARr " T h e s i s m 9 7 @ 1978 DAVID ALAN ORSEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The thesis of David A. Orsen is approved: University of Nevada Reno D ec|inber 1977 XI ABSTRACT Crystal Peak, Coal Valley and Coaldale lignites were deposited in penecontemporaneous environments containing similar floral assemblages indicating a uniform climatic regime may have existed over west-central Nevada during late Barstovian-early Clarendoni&n time. Palynological evidence indicates a late Duchesnean to early Chadronian age for the lignites at Elko. At Tick Canyon no definitive age was ascertained. At all locations, excepting Tick Canyon, field and palynologic evidence indicates low energy, shallow, fresh-water environments existed during the deposition of the lignite sequences. Pollen grains indicated that woodland communities dominated the landscape while mixed forests existed locally. Aquatic and marsh-like vegetation inhabited, and was primarily responsible for the in situ organic deposits in the shallower regions of the lakes. At each location, particularly at Tick Canyon, transported organic material noticeably contributed to the deposits. Past production is recorded from Coal Valley and Coaldale, however no future development seems feasible. PLEASE NOTE: This dissertation contains color photographs which will not reproduce -

BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT for the LUCAS Creek PROJECT KERN

Biological Assessment- Lucas Creek Project BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT For the LUCAS Creek PROJECT KERN RIVER RANGER DISTRICT SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST Kern County, California PREPARED By:--J; �ATE: February 5, 2018 Nina Hemphi Forest Fish Biologist/Aquatic Ecologist and Watershed Manager This Biological Assessment analyzes the potential impacts associated with implementation of the Lucas Creek Project on federal endangered and threatened species as identified under the Endangered Species Act. The environmental analysis evaluates the preferred alternative. The Lucas Creek Project includes removal of dead and dying trees on 250 acres on Breckenridge Mountain. The project area is located in sections 23, 24, 25, & 26, township 28 south, range 31 east, Mount Diablo Base Meridian on the Kern River Ranger District of the Sequoia National Forest. The project surrounds the Breckenridge subdivision on Breckenridge Mountain approximately 25 miles southwest of the town of Lake Isabella in Kern County California. The intent of the Lucas Creek Project is to remove hazard trees along roads and properties adjoining the Breckenridge Subdivision. The project would also reduce fuels build-up to protect the community and the Lucas Creek upper and middle watershed from high-intensity fire. This will improve forest resilience and watershed health. This document is prepared in compliance with the requirements of FSM 2672.4 and 36 CFR 219.19. Biological Assessment- Lucas Creek Project I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this Biological Assessment (BA) is to review the potential effects of Lucas Creek Project on species classified as federally endangered and threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA, 1973). Federally listed species are managed under the authority of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the National Forest Management Act (NFMA; PL 94- 588). -

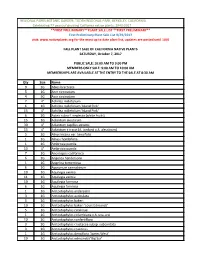

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

Wiest's Sphinx Moth

ATTACHMENT SS2 REGION 2 SENSITIVE SPECIES EVALUATION FORM Species: Wiest’s sphinx moth (Prairie sphinx moth) (Euproserpinus wiesti) Criteria Rank Rationale Literature Citations Species is documented only dune sheets east of Roggen, near Lamar, and Great • Smith, M.J. 1993. Moths of 1 A1 Sand Dunes. Species could well be at some additional dune localities but requires Distribution western North America. 2. within R2 Aeolian sand and caterpillar host Oenotheia latifolia. Distribution of Sphingidae of western North America. Confidence in Rank High Contribtions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Fort Collins, Colorado. • Opler, P.A. 2000. Euprosepinus wiestii in Association for Biodiversity Information online database [www.abi.org]. 2 B Also occurs in a few widely separated colonies in New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. • Smith, 1993. Distribution • Opler. 2000. outside R2 Confidence in Rank High Can fly but seem to be behaviorally sedentary. Flies at time of year when • Opler (personal assessment) 3 B temperatures are cool and sand dunes provide locally warmer areas. Dispersal Capability Confidence in Rank Medium 4 A Number of confirmed populations is limited about five colonies in region. • Smith (1993) Abundance in R2 Confidence in Rank Medium 5 B Believed to be stable but no available data on which to base opinion. • Opler (personal assessment) Population Trend in R2 Confidence in Rank Medium 6 B Believed to be stable but no available data on which to base opinion. • Opler (personal assessment) Habitat Trend in R2 Confidence in Rank Low USDA-Forest Service R2 Sensitive Species Evaluation Form Page 1 of 1 ATTACHMENT SS2 Species: Wiest’s sphinx moth (Prairie sphinx moth) (Euproserpinus wiesti) Criteria Rank Rationale Literature Citations 7 A Habitat is susceptible to trampling by livestock, and invasion of alien weeds. -

Archiv Für Naturgeschichte

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at Lepidoptera für 1903. Bearbeitet von Dr. Robert Lucas in Rixdorf bei Berlin. A. Publikationen (Autoren alphabetisch) mit Referaten. Adkin, Robert. Pyrameis cardui, Plusia gamma and Nemophila noc- tuella. The Entomologist, vol. 36. p. 274—276. Agassiz, G. Etüde sur la coloration des ailes des papillons. Lausanne, H. Vallotton u. Toso. 8 °. 31 p. von Aigner-Abafi, A. (1). Variabilität zweier Lepidopterenarten. Verhandlgn. zool.-bot. Ges. Wien, 53. Bd. p. 162—165. I. Argynnis Paphia L. ; IL Larentia bilineata L. — (2). Protoparce convolvuli. Entom. Zeitschr. Guben. 17. Jahrg. p. 22. — (3). Über Mimikry. Gaea. 39. Jhg. p. 166—170, 233—237. — (4). A mimicryröl. Rov. Lapok, vol. X, p. 28—34, 45—53 — (5). A Mimicry. Allat. Kozl. 1902, p. 117—126. — (6). (Über Mimikry). Allgem. Zeitschr. f. Entom. 7. Bd. (Schluß p. 405—409). Über Falterarten, welche auch gesondert von ihrer Umgebung, in ruhendem Zustande eine eigentümliche, das Auge täuschende Form annehmen (Lasiocampa quercifolia [dürres Blatt], Phalera bucephala [zerbrochenes Ästchen], Calocampa exoleta [Stück morschen Holzes]. — [Stabheuschrecke, Acanthoderus]. Raupen, die Meister der Mimikry sind. Nachahmung anderer Tiere. Die Mimik ist in vielen Fällen zwecklos. — Die wenn auch recht geistreichen Mimikry-Theorien sind doch vielleicht nur ein müßiges Spiel der Phantasie. Aitken u. Comber, E. A list of the butterflies of the Konkau. Journ. Bombay Soc. vol. XV. p. 42—55, Suppl. p. 356. Albisson, J. Notes biologiques pour servir ä l'histoire naturelle du Charaxes jasius. Bull. Soc. Etud. Sc. nat. Nimes. T. 30. p. 77—82. Annandale u. Robinson. Siehe unter S w i n h o e. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

North American Species of Cerambycid Beetles in the Genus Neoclytus Share a Common Hydroxyhexanone-Hexanediol Pheromone Structural Motif

FOREST ENTOMOLOGY North American Species of Cerambycid Beetles in the Genus Neoclytus Share a Common Hydroxyhexanone-Hexanediol Pheromone Structural Motif ANN M. RAY,1,2 JOCELYN G. MILLAR,3 JARDEL A. MOREIRA,3 J. STEVEN MCELFRESH,3 4,5 6 4 ROBERT F. MITCHELL, JAMES D. BARBOUR, AND LAWRENCE M. HANKS J. Econ. Entomol. 108(4): 1860–1868 (2015); DOI: 10.1093/jee/tov170 ABSTRACT Many species of cerambycid beetles in the subfamily Cerambycinae are known to use male-produced pheromones composed of one or a few components such as 3-hydroxyalkan-2-ones and the related 2,3-alkanediols. Here, we show that this pheromone structure is characteristic of the ceram- bycine genus Neoclytus Thomson, based on laboratory and field studies of 10 species and subspecies. Males of seven taxa produced pheromones composed of (R)-3-hydroxyhexan-2-one as a single compo- nent, and the synthetic pheromone attracted adults of both sexes in field bioassays, including the eastern North American taxa Neoclytus caprea (Say), Neoclytus mucronatus mucronatus (F.), and Neoclytus scu- tellaris (Olivier), and the western taxa Neoclytus conjunctus (LeConte), Neoclytus irroratus (LeConte), and Neoclytus modestus modestus Fall. Males of the eastern Neoclytus acuminatus acuminatus (F.) and the western Neoclytus tenuiscriptus Fall produced (2S,3S)-2,3-hexanediol as their dominant or sole pheromone component. Preliminary data also revealed that males of the western Neoclytus balteatus LeConte produced a blend of (R)-3-hydroxyhexan-2-one and (2S,3S)-2,3-hexanediol but also (2S,3S)- 2,3-octanediol as a minor component. The fact that the hydroxyketone-hexanediol structural motif is consistent among these North American species provides further evidence of the high degree of conservation of pheromone structures among species in the subfamily Cerambycinae.