Chronology of Vesuvius Activity from A.D. 79 to 1631 Based On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publication of an Application for Approval of a Minor

C 253/14 EN Official Journal of the European Union 4.8.2017 OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of an application for approval of a minor amendment in accordance with the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2017/C 253/11) The European Commission has approved this minor amendment in accordance with the third subparagraph of Article 6(2) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 664/2014 (1). APPLICATION FOR APPROVAL OF A MINOR AMENDMENT Application for approval of a minor amendment in accordance with the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council (2) ‘POMODORINO DEL PIENNOLO DEL VESUVIO’ EU No: IT-PDO-02146 – 24.6.2016 PDO ( X ) PGI ( ) TSG ( ) 1. Applicant group and legitimate interest Consorzio di Tutela del Pomodorino del Piennolo del Vesuvio DOP Piazza Meridiana 47 80040 San Sebastiano al Vesuvio (NA) ITALIA Tel.: +39 0810606007 Email: [email protected] The protection association ‘Consorzio di Tutela del Pomodorino del Piennolo del Vesuvio DOP’ is entitled to sub mit an application for registration pursuant to Article 13(1) of Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policy Decree No 12511 of 14 October 2013. 2. Member State or Third Country Italy 3. Heading in the product specification affected by the amendment(s) — Description of product — Proof of origin — Production method — Link — Labelling — Other [legal references and inspection body updates] 4. Type of amendment(s) — Amendment to product specification of registered PDO or PGI to be qualified as minor in accordance with the third subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012, that requires no amendment to the published single document. -

CALENDARS by David Le Conte

CALENDARS by David Le Conte This article was published in two parts, in Sagittarius (the newsletter of La Société Guernesiaise Astronomy Section), in July/August and September/October 1997. It was based on a talk given by the author to the Astronomy Section on 20 May 1997. It has been slightly updated to the date of this transcript, December 2007. Part 1 What date is it? That depends on the calendar used:- Gregorian calendar: 1997 May 20 Julian calendar: 1997 May 7 Jewish calendar: 5757 Iyyar 13 Islamic Calendar: 1418 Muharaim 13 Persian Calendar: 1376 Ordibehesht 30 Chinese Calendar: Shengxiao (Ox) Xin-You 14 French Rev Calendar: 205, Décade I Mayan Calendar: Long count 12.19.4.3.4 tzolkin = 2 Kan; haab = 2 Zip Ethiopic Calendar: 1990 Genbot 13 Coptic Calendar: 1713 Bashans 12 Julian Day: 2450589 Modified Julian Date: 50589 Day number: 140 Julian Day at 8.00 pm BST: 2450589.292 First, let us note the difference between calendars and time-keeping. The calendar deals with intervals of at least one day, while time-keeping deals with intervals less than a day. Calendars are based on astronomical movements, but they are primarily for social rather than scientific purposes. They are intended to satisfy the needs of society, for example in matters such as: agriculture, hunting. migration, religious and civil events. However, it has also been said that they do provide a link between man and the cosmos. There are about 40 calendars now in use. and there are many historical ones. In this article we will consider six principal calendars still in use, relating them to their historical background and astronomical foundation. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

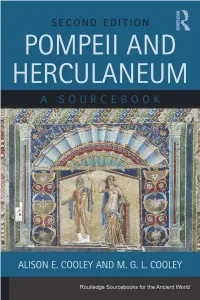

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

The Magma Feeding System of Somma-Vesuvius (Italy) Strato-Volcano 185

Else_DV-DEVIVO_ch009.qxd 3/2/2006 2:53 PM Page 183 Volcanism in the Campania Plain: Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ignimbrites edited by B. De Vivo © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 183 1 2 3 4 Chapter 9 5 6 The magma feeding system of Somma-Vesuvius (Italy) 7 strato-volcano: new inferences from a review of geochemical 8 and Sr, Nd, Pb and O isotope data 9 10 1 Monica Piochia,∗, Benedetto De Vivob and Robert A. Ayusoc 2 aIstituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Osservatorio Vesuviano, Napoli, Italy 3 bDipartimento di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Università Federico II, Napoli, Italy 4 cU.S. Geological Survey, MS 954 National Center, Reston, VA, USA 5 6 Abstract 7 A large database of major, trace and isotope (Sr, Nd, Pb, O) data exists for rocks produced by the volcanic activity 8 of Somma-Vesuvius volcano. Variation diagrams strongly suggest a major role for evolutionary processes such 9 as fractional crystallization, contamination, crystal trapping and magma mixing, occurring after magma genesis 20 in the mantle. Most mafic magmas are enriched in LILE (K, Rb, Ba), REE (Ce, Sm) and Y, show small Nb–Ta AQ1 1 negative anomalies, and have values of Nb/Zr at about 0.15. Enrichments in LILE, REE, Nb and Ta do not 2 correlate with Sr isotope values or degree of both K enrichment and silica undersaturation. The results indicate mantle source heterogeneity produced by slab-derived components beneath the volcano. However, the Sr isotope 3 values of Somma-Vesuvius increase from 0.7071 up to 0.7081 with transport through the uppermost 11–12 km 4 of the crust. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

The Vesuvius and the Other Volcanoes of Central Italy

Geological Field Trips Società Geologica Italiana 2017 Vol. 9 (1.1) I SPRA Dipartimento per il SERVIZSERVIZIOIO GGEOLOGICOEOLOGICO D’ITALIAD’ITALIA Organo Cartografico dello Stato (legge n°68 del 2-2-1960) ISSN: 2038-4947 The Vesuvius and the other volcanoes of Central Italy Goldschmidt Conference - Florence, 2013 DOI: 10.3301/GFT.2017.01 The Vesuvius and the other volcanoes of Central Italy R. Avanzinelli - R. Cioni - S. Conticelli - G. Giordano - R. Isaia - M. Mattei - L. Melluso - R. Sulpizio GFT - Geological Field Trips geological fieldtrips2017-9(1.1) Periodico semestrale del Servizio Geologico d'Italia - ISPRA e della Società Geologica Italiana Geol.F.Trips, Vol.9 No.1.1 (2017), 158 pp., 107 figs. (DOI 10.3301/GFT.2017.01) The Vesuvius and the other volcanoes of Central Italy Goldschmidt Conference, 2013 Riccardo Avanzinelli1, Raffaello Cioni1, Sandro Conticelli1, Guido Giordano2, Roberto Isaia3, Massimo Mattei2, Leone Melluso4, Roberto Sulpizio5 1. Università degli Studi di Firenze 2. Università degli Studi di Roma 3 3. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia 4. Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II” 5. Università degli Studi di Bari Corresponding Authors e-mail addresses: [email protected] - [email protected] Responsible Director Claudio Campobasso (ISPRA-Roma) Editorial Board Editor in Chief M. Balini, G. Barrocu, C. Bartolini, 2 Gloria Ciarapica (SGI-Perugia) D. Bernoulli, F. Calamita, B. Capaccioni, Editorial Responsible W. Cavazza, F.L. Chiocci, Maria Letizia Pampaloni (ISPRA-Roma) R. Compagnoni, D. Cosentino, S. Critelli, G.V. Dal Piaz, C. D'Ambrogi, Technical Editor publishing group Mauro Roma (ISPRA-Roma) P. Di Stefano, C. -

Vesuvius Near Naples

THE LACRIMA CHRISTI OF MOUNT VESUVIUS NEAR NAPLES This is an attempt to create what Edward L. Ayers refers to, in his piece “Mapping Time,” as “deep contingency”: “layers of events, layers of the consequences of unpredictability.” Precisely as the lava flows accumulate on the flanks of Vesuvius, we will attempt to depict how centuries accumulate. July 7, Monday, 1851: ...Even the facts of science may dust the mind by their dryness –unless they are in a sense effaced each morning or rather rendered fertile by the dews of fresh & living truth. Every thought that passes through the mind helps to wear & tear it & to deepen the ruts which as in the streets of Pompeii evince how much it has been used. How many things there are concerning which we might well deliberate whether we had better know them. Routine –conventionality manners &c &c –how insensibly and undue attention to these dissipates & impoverishes the mind –robs it of its simplicity & strength emasculates it. Knowledge doe[s] not cone [come] to us by details but by lieferungs from the gods. What else is it to wash & purify ourselves? Conventionalities are as bad as impurities. Only thought which is expressed by the mind in repose as it wer[e] lying on its back & contemplating the heaven’s –is adequately & fully expressed– What are side long –transient passing half views? The writer expressing his thought –must be as well seated as the astronomer contemplating the heavens –he must not occupy a constrained position. The facts the experience we are well poised upon –! Which secures our whole attention! HDT WHAT? INDEX VESUVIO NAPLES [Bulfinch’s MYTHOLOGY] The region where Virgil locates the entrance to this abode is perhaps the most strikingly adapted to excite ideas of the terrific and preternatural of any on the face of the earth. -

Vologases I, Pakoros Ii and Artabanos Iii: Coins and Parthian History1

IranicaAntiqua, vol. LI, 2016 doi: 10.2143/IA.51.0.3117835 VOLOGASES I, PAKOROS II AND ARTABANOS III: COINS AND PARTHIAN HISTORY1 BY Marek Jan OLBRYCHT (University of Rzeszów) Abstract: This article focuses on certain aspects of Parthian coinage under Vologases I (51-79) and Pakoros II (78-110). Most studies convey a picture of extreme political confusion in Parthia at the close of Vologases I’s reign to that of the beginning of Pakoros II’s. They also tend to clump together Vologases I, “Vologases II”, Artabanos III, and Pakoros II as though they were all rival kings, each striving to usurp the throne. Changes in the minting practice of the Arsacids were strictly connected with political transformations that were occurring in Parthia at that time. Any attribution of coin types along with an analysis of the nature of monetary issues depends on an accurate reconstruction of the political developments that effected them. Keywords: Arsacids, Parthian coinage, Vologases I, Pakoros I, Artabanos III This article focuses on certain aspects of Parthian coinage under Vologases I (51-79) and Pakoros II (78-110). Changes in the minting prac- tice of the Arsacids were strictly connected with political transformations that were occurring in Parthia at that time. Any attribution of coin types along with an analysis of the nature of monetary issues (including new royal titles, kings’ names or insignia) depends on an accurate reconstruc- tion of the political developments that effected them, an area subject to impassioned controversy and prone to shaky conclusions. One of the chief aprioristic assumptions some specialists tend to adopt is the belief that any temporal overlap of monetary issues is a sure indication of internal strife in Parthia. -

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500 Previewing Main Ideas POWER AND AUTHORITY Rome began as a republic, a government in which elected officials represent the people. Eventually, absolute rulers called emperors seized power and expanded the empire. Geography About how many miles did the Roman Empire stretch from east to west? EMPIRE BUILDING At its height, the Roman Empire touched three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa. For several centuries, Rome brought peace and prosperity to its empire before its eventual collapse. Geography Why was the Mediterranean Sea important to the Roman Empire? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Out of Judea rose a monotheistic, or single-god, religion known as Christianity. Based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, it soon spread throughout Rome and beyond. Geography What geographic features might have helped or hindered the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 152 153 What makes a successful leader? You are a member of the senate in ancient Rome. Soon you must decide whether to support or oppose a powerful leader who wants to become ruler. Many consider him a military genius for having gained vast territory and wealth for Rome. Others point out that he disobeyed orders and is both ruthless and devious. You wonder whether his ambition would lead to greater prosperity and order in the empire or to injustice and unrest. ▲ This 19th-century painting by Italian artist Cesare Maccari shows Cicero, one of ancient Rome’s greatest public speakers, addressing fellow members of the Roman Senate. -

Related Events

June 26 to October 28, 2019 At the Getty Villa RELATED EVENTS L E C T U R E S The Future of the Past at Herculaneum Thursday, June 27, 2019, at 7:30 pm The Getty Villa, Auditorium Free | Advance ticket required Francesco Sirano, director of the Archaeological Park of Herculaneum, discusses the past, present, and future of the site buried by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79. Excavated since 1738, a decade before nearby Pompeii, Herculaneum presents challenges and opportunities different from its more famous neighbor. Sirano addresses exciting new finds, conservation issues, and recent efforts to boost public awareness and engagement. This lecture complements the exhibition Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri, which will be open before and after the lecture. It is presented in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute, Los Angeles. Francesco Sirano is an archaeologist and the director of the Parco Archeologico di Ercolano. His extensive museum management experience was honed at the Museo Archeologico e Teatro dell’antica Teanum Sidicinum, the Museo Archeologico antica Allifae, the Museo Archeologico e Circuito siti dell’Antica Capua, and the Parchi Archeologici di Baia e Cuma. Among his many research interests are Greco-Roman archaeology, the study of the image, and material culture. http://www.getty.edu/visit/cal/events/ev_2733.html The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 F O O D Bacchus Uncorked: Drinking and Thinking Saturday, July 13, 2019, from 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm The Getty Villa Advance ticket required Luxury Roman villas offered the leisure to discuss important topics—such as leading a good life—over wine. -

A Framework for Probabilistic Multi-Hazard Assessment of Rain-Triggered Lahars Using Bayesian Belief Networks

Tierz, P. , Woodhouse, M., Phillips, J., Sandri, L., Selva, J., Marzocchi, W., & Odbert, H. (2017). A Framework for Probabilistic Multi-Hazard Assessment of Rain-Triggered Lahars Using Bayesian Belief Networks. Frontiers in Earth Science, 5, [73]. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2017.00073 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.3389/feart.2017.00073 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Frontiers at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/feart.2017.00073/full. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 11 September 2017 doi: 10.3389/feart.2017.00073 A Framework for Probabilistic Multi-Hazard Assessment of Rain-Triggered Lahars Using Bayesian Belief Networks Pablo Tierz 1*†, Mark J. Woodhouse 2, Jeremy C. Phillips 2, Laura Sandri 1, Jacopo Selva 1, Warner Marzocchi 3 and Henry M. Odbert 2, 4 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2 School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom, 3 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Roma, Rome, Italy, 4 Met Office, Exeter, United Kingdom Volcanic water-sediment flows, commonly known as lahars, can often pose a higher threat to population and infrastructure than primary volcanic hazardous processes such as tephra fallout and Pyroclastic Density Currents (PDCs).