1 Pompeii & Herculaneum Archaeological Sites: Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City in the Sand Ebook

CITY IN THE SAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Chubb | 213 pages | 29 Jan 2000 | Libri Publications Ltd | 9781901965025 | English | London, United Kingdom City in the Sand PDF Book Guests staying in any of The Castle accommodations will find The Castle is the perfect beachfront and oceanfront location. That has to be rare indeed. Open Preview See a Problem? I thought was an excellent addition to the main book. If the artifacts are indeed prehistoric stone tools, then it means humans settled on the shores of ancient Pleistocene lake more than 30, years ago. The well was the only permanent watering place in those parts and, being a necessary watering place for Bedouin raiders, had been the scene of many fierce encounters in the past, [12]. According to those overseeing the project, Neom has already invited tenders from a range of international firms, while plans are moving forward to build a road bridge to Egypt. In the valley of the Tombs, to the east of the city, the "houses of the dead," veritable underground palaces, were decorated with particularly fine sculpture and frescoes. Most tales of the lost city locate it somewhere in the Rub' al Khali desert, also known as the Empty Quarter, a vast area of sand dunes covering most of the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula , including most of Saudi Arabia and parts of Oman , the United Arab Emirates , and Yemen. Biotech City of the Future Healthcare. Original Title. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Emir Fakhr ad-Din was still using Palmyra as a place to exercise his police, however he was anxious to have greater security than offered by the ruined city, so he had a castle built on the hillside overlooking it. -

PPS Newsletter April 2008 Information to Polymer Processing Society Members

PPS Newsletter www.tpps.org April 2008 Information to Polymer Processing Society Members PPS-24 in Salerno, Italy, the biggest to date? The beautiful and historic city of Salerno, Italy, is situated 60 km south of Naples and offers an enchanting view of the scenery of the Gulf of Salerno facing the magnificent Amalfi Coast. Nearby are the ancient sites of Pompei and Paestum. Salerno has escaped mass tourism, and it is “authentically Italian”, with a historic center, an ancient castle overlooking the city and the bay, and a long seafront promenade. Its marvelous year-round climate makes it possible to enjoy a “typical Italian” outdoor lifestyle. It will be the location of the PPS-24 annual meeting of the Polymer Processing Society (http://www.pps-24.com). The meeting will take place in June 15- 19, 2008. The venue will be the Grand Hotel Salerno right on the coast overlooking Salerno Bay. Around 1200 submissions for papers to present have been received from more than 40 countries from around the world, making it perhaps the biggest annual meeting ever of the PPS. The team of Prof. Giuseppe Titomanlio is working very hard to make this meeting a grand success. Map of Naples and Salerno Bays. One of the attractions of Salerno Grand Hotel Salerno, the Salerno, the site of PPS-24, is is the beautiful promenade near venue for the PPS-24 Annual located near the Amalfi Coast the Hotel and Conference Center. Meeting, overlooking Salerno (green arrow) and boasts many Bay. historical sites nearby (Pompei, Herculaneum, Paestum, etc). -

2021 Camp Spotlights

Pirate Adventures July 12-16, 2021 1:00-4:30 PM, $49 per day Make it a full day for $98 by adding a morning camp! Arrr-matey! It’s out to sea we go! Attention all scalliwags and explorers: Are your kids interested in sailing the seven seas, swinging on a rope, dropping into the sea, and building their own pirate ship? The life of a pirate is not for the couch-potato - get up and be active this summer at Airborne! Every day is a new adventure, and a new pirate joke of course! Monday: What does it take to be a Pirate? Campers will pick out their very own pirate name, and add their name to the crew list. Now that the campers are official Pirates, it’s time for them to explore some of the physical tasks pirates have to do. Using the different equipment like the ropes, trampoline, bars, ladders and balance beams we will learn how to climb, jump, swing and balance (for sword fighting) like a pirate. Each camper will get a turn to complete the Pirate Agility Obstacle Course, that includes each of these tasks, to earn gold coins. Tuesday: Battle at Sea! Pirates face so many challenges… can you get around with only one leg? Can you walk the plank without falling in? Can you defend your ship and sink the other ships in return? Can you earn your golden treasure? Come and sail the friendly seas, if you dare! Arrr! Wednesday: Building a Pirate Ship! Campers will learn about all the different parts of a pirate ship and then work as a crew and build their very own ship. -

CAPRI È...A Place of Dream. (Pdf 2,4

Posizione geografica Geographical position · Geografische Lage · Posición geográfica · Situation géographique Fra i paralleli 40°30’40” e 40°30’48”N. Fra i meridiani 14°11’54” e 14°16’19” Est di Greenwich Superficie Capri: ettari 400 Anacapri: ettari 636 Altezza massima è m. 589 Capri Giro dell’isola … 9 miglia Clima Clima temperato tipicamente mediterraneo con inverno mite e piovoso ed estate asciutta Between parallels Zwischen den Entre los paralelos Entre les paralleles 40°30’40” and 40°30’48” Breitenkreisen 40°30’40” 40°30’40”N 40°30’40” et 40°30’48” N N and meridians und 40°30’48” N Entre los meridianos Entre les méridiens 14°11’54” and 14°16’19” E Zwischen den 14°11’54” y 14°16’19” 14e11‘54” et 14e16’19“ Area Längenkreisen 14°11’54” Este de Greenwich Est de Greenwich Capri: 988 acres und 14°16’19” östl. von Superficie Surface Anacapri: 1572 acres Greenwich Capri: 400 hectáreas; Capri: 400 ha Maximum height Fläche Anacapri: 636 hectáreas Anacapri: 636 ha 1,920 feet Capri: 400 Hektar Altura máxima Hauter maximum Distances in sea miles Anacapri: 636 Hektar 589 m. m. 589 from: Naples 17; Sorrento Gesamtoberfläche Distancias en millas Distances en milles 7,7; Castellammare 13; 1036 Hektar Höchste marinas marins Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; Erhebung über den Nápoles 17; Sorrento 7,7; Naples 17; Sorrento 7,7; lschia 16; Positano 11 Meeresspiegel: 589 Castellammare 13; Castellammare 13; Amalfi Distance round the Entfernung der einzelnen Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; 17,5 Salerno 25; lschia A Place of Dream island Orte von Capri, in Ischia 16; Positano 11 16; Positano 11 9 miles Seemeilen ausgedrükt: Vuelta a la isla por mar Tour de l’ île par mer Climate Neapel 17, Sorrento 7,7; 9 millas 9 milles Typical moderate Castellammare 13; Amalfi Clima Climat Mediterranean climate 17,5; Salerno 25; lschia templado típicamente Climat tempéré with mild and rainy 16; Positano 11 mediterráneo con typiquement Regione Campania Assessorato al Turismo e ai Beni Culturali winters and dry summers. -

F. Pingue , G.. De Natale , , P. Capuano , P. De , U

Ground deformation analysis at Campi Flegrei (Southern Italy) by CGPS and tide-gauge network F. Pingue1, G.. De Natale1, F. Obrizzo1, C. Troise1, P. Capuano2, P. De Martino1, U. Tammaro1 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia . Osservatorio Vesuviano, Napoli, Italy 2 Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica, Università di Salerno, Italy CGPS CAMPI FLEGREI NETWORK TIDE GAUGES ABSTRACT GROUND DEFORMATION HISTORY CGPS data analysis, during last decade, allowed continuous and accurate The vertical ground displacements at Campi Flegrei are also tracked by the sea level using tide gauges located at the Campi Flegrei caldera is located 15 km west of the Campi Flegrei, a caldera characterized by high volcanic risk due to tracking of ground deformation affecting Campi Flegrei area, both for Nisida (NISI), Port of Pozzuoli (POPT), Pozzuoli South- Pier (POPT) and Miseno (MISE), in addition to the reference city of Naples, within the central-southern sector of a the explosivity of the eruptions and to the intense urbanization of the vertical component (also monitored continuously by tide gauge and one (NAPT), located in the Port of Naples. The data allowed to monitor all phases of Campi Flegrei bradyseism since large graben called Campanian Plain. It is an active the surrounding area, has been the site of significant unrest for the periodically by levelling surveys) and for the planimetric components, 1970's, providing results consistent with those obtained by geometric levelling, and more recently, by the CGPS network. volcanic area marked by a quasi-circular caldera past 2000 years (Dvorak and Mastrolorenzo, 1991). More recently, providing a 3D displacement field, allowing to better constrain the The data have been analyzed in the frequency domain and the local astronomical components have been defined by depression, formed by a huge ignimbritic eruption the caldera floor was raised to about 1.7 meters between 1968 and inflation/deflation sources responsible for ground movements. -

Stromboli Mount Fuji Ojos Del Salado Mauna Loa Mount Vesuvius Mount

Volcanoes Top Cards Volcanoes Top Cards Volcanoes Top Cards Volcanoes Top Cards Stromboli Mount Fuji Ojos del Salado Mauna Loa Italy Japan Argentina-Chile Border Hawaii Height Height Height Height Eruption Cycle Eruption Cycle Eruption Cycle Eruption Cycle Erupting continuously Last Erupted Last Erupted Last Erupted Last Erupted for hundreds of thousands of years Fact: This volcano is the highest Fact: Nevados Ojos del Salado is the Fact: Mauna Loa is one of the five Fact: This volcano has been erupting volcano and highest peak in world’s highest active volcano. volcanoes that form the Island of for at least 2000 years. Japan and considered one of the 3 Hawaii in the U.S state of Hawaii in holy mountains. the Pacific Ocean. twinkl.com twinkl.com twinkl.com twinkl.com Volcanoes Top Cards Volcanoes Top Cards Volcanoes Top Cards Volcanoes Top Cards Mount Vesuvius Mount Pinatubo Krakatoa Mount St. Helens Italy Philippines Indonesia United States Height Height Height Height Eruption Cycle Eruption Cycle Eruption Cycle Eruption Cycle Last Erupted Last Erupted Last Erupted Last Erupted Fact: The most famous eruption Fact: Mount Pinatubo’s eruption Fact: The famous eruption of 1883 Fact: The deadliest volcanic eruption happened in 79 AD. Mount Vesuvius on 15th June 1991 was one of the generated the loudest sound ever caused by this volcano was on erupted continuously for over a day, largest volcanic eruptions of the reported in history. It was heard as May 18, 1980, destroying 250 completely burying the nearby city 20th Century. far away as Perth, Australia (around homes and 200 miles of highway. -

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

Boccaccio Angioino Materiali Per La Storia Culturale Di Napoli Nel Trecento

Giancarlo Alfano, Teresa D'Urso e Alessandra Perriccioli Saggese (a cura di) Boccaccio angioino Materiali per la storia culturale di Napoli nel Trecento Destini Incrociati n° 7 5 1-6.p65 5 19/03/2012, 14:25 Il presente volume è stato stampato con i fondi di ricerca della Seconda Università di Napoli e col contributo del Dipartimento di Studio delle componenti culturali del territorio e della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia. Si ringraziano Antonello Frongia ed Eliseo Saggese per il prezioso aiuto offerto. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’éditeur ou de ses ayants droit, est illicite. Tous droits réservés. © P.I.E. PETER LANG S.A. Éditions scientifiques internationales Bruxelles, 2012 1 avenue Maurice, B-1050 Bruxelles, Belgique www.peterlang.com ; [email protected] Imprimé en Allemagne ISSN 2031-1311 ISBN 978-90-5201-825-6 D/2012/5678/29 Information bibliographique publiée par « Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek » « Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek » répertorie cette publication dans la « Deutsche Nationalbibliografie » ; les données bibliographiques détaillées sont disponibles sur le site http://dnb.d-nb.de. 6 1-6.p65 6 19/03/2012, 14:25 Indice Premessa ............................................................................................... 11 In forma di libro: Boccaccio e la politica degli autori ...................... 15 Giancarlo Alfano Note sulla sintassi del periodo nel Filocolo di Boccaccio .................. 31 Simona Valente Appunti di poetica boccacciana: l’autore e le sue verità .................. 47 Elisabetta Menetti La “bona sonoritas” di Calliopo: Boccaccio a Napoli, la polifonia di Partenope e i silenzi dell’Acciaiuoli ........................... 69 Roberta Morosini «Dal fuoco dipinto a quello che veramente arde»: una poetica in forma di quaestio nel capitolo VIII dell’Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta ................................................... -

Summary of the Periodic Report on the State of Conservation, 2006

State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties in Europe SECTION II discovered, such as the Central Baths, the Suburban Baths, the College of the Priests of ITALY Augustus, the Palestra and the Theatre. The presence, in numerous houses, of furniture in carbonised wood due to the effects of the eruption Archaeological Areas of Pompei, is characteristic of Herculaneum. Hercolaneum and Torre The Villa of Poppea is preserved in exceptional way Annunziata and is one of the best examples of residential roman villa. The Villa of Cassius Tertius is one of Brief description the best examples of roman villa rustica. When Vesuvius erupted on 24 August A.D. 79, it As provided in ICOMOS evaluation engulfed the two flourishing Roman towns of Pompei and Herculaneum, as well as the many Qualities: Owing to their having been suddenly and wealthy villas in the area. These have been swiftly overwhelmed by debris from the eruption of progressively excavated and made accessible to Vesuvius in AD 79, the ruins of the two towns of the public since the mid-18th century. The vast Pompei and Herculaneum are unparalleled expanse of the commercial town of Pompei anywhere in the world for their completeness and contrasts with the smaller but better-preserved extent. They provide a vivid and comprehensive remains of the holiday resort of Herculaneum, while picture of Roman life at one precise moment in the superb wall paintings of the Villa Oplontis at time. Torre Annunziata give a vivid impression of the Recommendation: That this property be inscribed opulent lifestyle enjoyed by the wealthier citizens of on the World Heritage List on the basis of criteria the Early Roman Empire. -

SPECIALE BORGHI Della CAMPANIA2

SPECIALE BORGHI della CAMPANIA2 COPIA OMAGGIO edizione speciale FIERE un parco di terra e di mare laboratorio di biodiversità a park of land and sea R laboratory of biodiversity www.cilentoediano.it GLI 80 COMUNI DEL PARCO NAZIONALE DEL CILENTO VALLO DI DIANO E ALBURNI Agropoli Gioi Roccagloriosa Aquara Giungano Rofrano Ascea Laureana Cilento Roscigno Auletta Laurino Sacco Bellosguardo Laurito Salento Buonabitacolo Lustra San Giovanni a Piro Camerota Magliano Vetere San Mauro Cilento Campora Moio della Civitella San Mauro la Bruca Cannalonga Montano Antilia San Pietro al Tanagro Capaccio Monte San Giacomo San Rufo Casal velino Montecorice Sant’Angelo a Fasanella Casalbuono Monteforte Cilento Sant’Arsenio Casaletto Spartano Montesano sulla Marcellana Santa Marina Caselle in Pittari Morigerati Sanza Castel San Lorenzo Novi Velia Sassano Castelcivita Omignano Serramezzana Castellabate Orria Sessa Cilento Castelnuovo Cilento Ottati Sicignano degli Alburni Celle di Bulgheria Perdifumo Stella Cilento Centola Perito Stio Ceraso Petina Teggiano Cicerale Piaggine Torre Orsaia Controne Pisciotta Tortorella Corleto Monforte Polla Trentinara Cuccaro Vetere Pollica Valle dell’Angelo Felitto Postiglione Vallo della Lucania Futani Roccadaspide I 15 COMUNI NELLE AREE CONTIGUE DEL PARCO NAZIONALE DEL CILENTO VALLO DI DIANO E ALBURNI Albanella Ogliastro Cilento Sala Consilina Alfano Padula Sapri Atena Lucana Pertosa Torchiara Caggiano Prignano Cilento Torraca Ispani Rutino Vibonati zona del parco Parco Nazionale del Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni Ai Focei si deve, invece, la fondazione di Velia (VI secolo a.C.), patria della scuola Eleatica di Parmenide che ha fecon- dato e illuminato la storia della filosofia occidentale. La Certosa di San Lorenzo di Padula costituisce un vero e proprio gioiello dell’architettura monastica, principale esem- pio del Barocco del Mezzogiorno, inserita tra i Monumenti Internazionali già nel lontano 1882. -

Robert Harris • Enigma

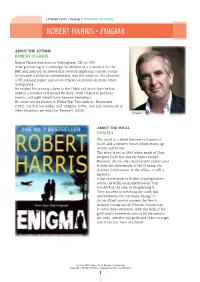

LITERARY BITS Module 2 WORKING IN DIGITAL ROBERT HARRIS • ENIGMA ABOUT THE AUTHOR ROBERT HARRIS Robert Harris was born in Nottingham, UK, in 1957. After graduating at Cambridge, he worked as a journalist for the BBC and assisted on shows that covered important current events. He became a political commentator, was the editor of The Observer, a UK political paper, and wrote articles on politics in many other newspapers. He started his writing career in the 1980s and since then he has written a number of fictional thrillers, often related to political events, and eight novels have become bestsellers. He wrote novels related to World War Two such as ‘Fatherland’ (1992), his first bestseller, and ‘Enigma’ (1995), but also stories set in other historical periods like ‘Pompeii’ (2003). R. Harris ABOUT THE NOVEL ENIGMA The novel is a blend between a historical novel and a mystery novel which mixes up reality and fiction. The story is set in 1943 when much of Nazi Enigma Code has already been cracked. However, Shark, the impenetrable cipher used to hide the movements of the U-boats, the German submarines, to the Allies, is still a mystery. A top secret team of British cryptographers led by the brilliant mathematician Tom Jericho has the task of deciphering it. They succeed in breaking the code, but unfortunately the Germans change it. As an Allied convoy crosses the North Atlantic Ocean full of U-boats, Jericho has to solve three mysteries with the help of his girlfriend’s roommate who is on the convoy: the code, whether his girlfriend Claire is a spy and if she has been murdered. -

Mount Vesuvius Is Located on the Gulf of Naples, in Italy

Mount Vesuvius is located on the Gulf of Naples, in Italy. It is close to the coast and lies around 9km from the city of Naples. Despite being the only active volcano on mainland Europe, and one of the most dangerous volcanoes, almost 3 million people live in the immediate area. Did you know..? Mount Vesuvius last erupted in 1944. Photo courtesy of Ross Elliot(@flickr.com) - granted under creative commons licence – attribution Mount Vesuvius is one of a number of volcanoes that form the Campanian volcanic arc. This is a series of volcanoes that are active, dormant or extinct. Vesuvius Campi Flegrei Stromboli Mount Vesuvius is actually a Vulcano Panarea volcano within a volcano. Mount Etna Somma is the remain of a large Campi Flegrei del volcano, out of which Mount Mar di Sicilia Vesuvius has grown. Did you know..? Mount Vesuvius is 1,281m high. Mount Etna is another volcano in the Campanian arc. It is Europe’s most active volcano. Mount Vesuvius last erupted in 1944. This was during the Second World War and the eruption caused great problems for the newly arrived Allied forces. Aircraft were destroyed, an airbase was evacuated and 26 people died. Three villages were also destroyed. 1944 was the last recorded eruption but scientists continue to monitor activity as Mount Vesuvius is especially dangerous. Did you know..? During the 1944 eruption, the lava flow stopped at the steps of the local church in the village of San Giorgio a Cremano. The villagers call this a miracle! Photo courtesy of National Museum of the U.S.