The Birth of Dionysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN by Sarah Kellis Jennings Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Theatre Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 3, 2013 ii STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN Project Approved: T.J. Walsh, Ph.D. Department of Theatre (Supervising Professor) Harry Parker, Ph.D. Department of Theatre Kindra Santamaria, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 GREEK THEATRE .............................................................................................................1 The Dithyramb ................................................................................................................2 Grecian Tragedy .............................................................................................................4 The Greek Actor ............................................................................................................. 8 The Satyr Play ................................................................................................................9 The Greek Theatre Structure and Technical Flourishes ...............................................10 Grecian -

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou ACCHYLIDES 17, a Cean commission performed on Delos, has been the subject of extensive study and is Bmuch admired for its narrative artistry, elegance, and excellence. The ode was classified as a dithyramb by the Alex- andrians, but the Du-Stil address to Apollo in the closing lines renders this classification problematic and has rather baffled scholars. The solution to the thorny issue of the ode’s generic taxonomy is not yet conclusive, and the dilemma paean/ dithyramb is still alive.1 In fact, scholars now are more inclined to place the poem somewhere in the middle, on the premise that in antiquity the boundaries between dithyramb and paean were not so clear-cut as we tend to believe.2 Even though I am 1 Paean: R. Merkelbach, “Der Theseus des Bakchylides,” ZPE 12 (1973) 56–62; L. Käppel, Paian: Studien zur Geschichte einer Gattung (Berlin 1992) 156– 158, 184–189; H. Maehler, Die Lieder des Bakchylides II (Leiden 1997) 167– 168, and Bacchylides. A Selection (Cambridge 2004) 172–173; I. Rutherford, Pindar’s Paeans (Oxford 2001) 35–36, 73. Dithyramb: D. Gerber, “The Gifts of Aphrodite (Bacchylides 17.10),” Phoenix 19 (1965) 212–213; G. Pieper, “The Conflict of Character in Bacchylides 17,” TAPA 103 (1972) 393–404. D. Schmidt, “Bacchylides 17: Paean or Dithyramb?” Hermes 118 (1990) 18– 31, at 28–29, proposes that Ode 17 was actually an hyporcheme. 2 B. Zimmermann, Dithyrambos: Geschichte einer Gattung (Hypomnemata 98 [1992]) 91–93, argues that Ode 17 was a dithyramb for Apollo; see also C. -

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle Much recent work has enhanced our understanding of dithyramb’s identity as a “circular chorus,” primarily by clarifying the ancient use of the phrase “circular chorus” as a label for dithyramb (Käppel 2000; Fearn 2007, ch. 3; Ceccarelli 2013; D’Alessio 2013). Little of that work, however, has investigated the meaning of the phrase “circular chorus,” which is most often assumed to refer to dithyramb’s distinctive choreography, whereby the members of a dithyrambic chorus danced while arranged in a circle around a central object (Fearn 2007: 165-7; Ceccarelli 2013: 162; earlier, Pickard-Cambridge 1962: 32 and 1988: 77). In this paper, I examine one of the earliest moments from the literary record of ancient Greece when dithyramb is called a “circular chorus,” the appearance of the dithyrambic poet Cinesias in Aristophanes’ Birds (1373-1409). I argue that when Aristophanes refers to dithyramb as a “circular chorus” here, he evokes not just the genre’s choreography, but also its vocabulary, poetic structure, and modes of expression and thought. In Birds, the poet Cinesias arrives in Cloudcuckooland boasting of the excellence of his “dithyrambs” (τῶν διθυράμβων, 1388) and promoting himself as a “poet of circular choruses” (τὸν κυκλιοδιδάσκαλον, 1403), thus equating the genre of dithyramb with the label “circular chorus.” Scholars have long noted that, upon Cinesias’ entrance, Peisetaerus alludes to circular dancing with his question “Why do you circle your deformed foot here in a circle?” (τί δεῦρο πόδα σὺ κυλλὸν ἀνὰ κύκλον κυκλεῖς;, 1378; cf. Lawler 1950; Sommerstein 1987: 290; Dunbar 1995: 667-8). -

Attic Dramamailversion.Pptx

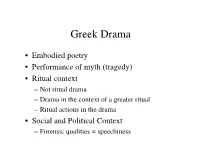

Greek Drama • Embodied poetry • Performance of myth (tragedy) • Ritual context – Not ritual drama – Drama in the context of a greater ritual – Ritual actions in the drama • Social and Political Context – Forensic qualities = speechiness Athenian Dramatic Festivals • The audience: 10-14,000 people, mostly Athenian male citizens, sometimes foreign dignitaries • Poets “applied” for a chorus 6 months before. • Competition during religious festivals for the god Dionysus – City Dionysia (April/March) open to foreign visitors – Lenaia (January) more “closed” to outsiders Performances of: Tragedies (oldest form) (9 plays by 3 tragic poets) Satyr plays (3 plays by the 3 tragic poets) Comedies (1 each by 3 to 5 comic poets) Dithyrambs (10 choruses of men, 10 of boys) Audience saw 4 or 5 plays a day, for three or four days. Tragic mornings, comic afternoons. Other official business was done as well. Evolution of Genres • dithyramb (hymn in honor of Dionysus) • tragedy (diverged from Dionysian themes) – Thespis, 534 BC • satyr play (reinserted Dionysian themes) – included 502-501 BC • Comedy <= from the komos (revelry) ca. 486 BC Origins of Phallic Procession A phallos is a long piece of timber fitted with leather genitalia at the top. The phallos came to be part of the worship of Dionysus by some secret rite. About the phallos itself the following is said. Pegasos took the image of Dionysus from Eleutherai—Eleutherai is a city of Boeotia [a region neighboring Attica, the region of Athens]—and brought it to Attica. The Athenians, however, did not receive the god with reverence, but they did not get away with this resolve unpunished, because, since the god was angry, a disease [priapism?] attacked the men’s genitals and the calamity was incurable. -

Pindar Fr. 75 SM and the Politics of Athenian Space Richard T

Pindar Fr. 75 SM and the Politics of Athenian Space Richard T. Neer and Leslie Kurke Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow. Anne Carson, “The Life of Towns” T IS WELL KNOWN that Pindar’s poems were occasional— composed on commission for specific performance settings. IBut they were also, we contend, situational: mutually im- plicated with particular landscapes, buildings, and material artifacts. Pindar makes constant reference to precious objects and products of craft, both real and metaphorical; he differs, in this regard, from his contemporary Bacchylides. For this reason, Pindar provides a rich phenomenology of viewing, an insider’s perspective on the embodied experience of moving through a built environment amidst statues, buildings, and other monu- ments. Analysis of the poetic text in tandem with the material record makes it possible to reconstruct phenomenologies of sculpture, architecture, and landscape. Our example in this essay is Pindar’s fragment 75 SM and its immediate context: the cityscape of early Classical Athens. Our hope is that putting these two domains of evidence together will shed new light on both—the poem will help us solve problems in the archaeo- logical record, and conversely, the archaeological record will help us solve problems in the poem. Ultimately, our argument will be less about political history, and more about the ordering of bodies in space, as this is mediated or constructed by Pindar’s poetic sophia. This is to attend to the way Pindar works in three dimensions, as it were, to produce meaningful relations amongst entities in the world.1 1 Interest in Pindar and his material context has burgeoned in recent ————— Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 54 (2014) 527–579 2014 Richard T. -

A Complete List of Terms to Know

Classical Drama and Theatre: A Complete List of Terms to Know Terms to Know From Section 1: Chapter 1 Theatre History Theatron Historiography Institution Historia Theatrical Herodotus Language Ionian Revolution Impersonation Primary Evidence Audience Secondary Evidence Positivism Inference Progress Cogent Primitive Tripartition E.K. Chambers Battle of Thermopylae Chorus Ibn Kahldun Chapter 2 Transitional Forms Herodotus Bronislaw Malinowski The Histories Aetiological Relics Claude Levi-Strauss Fossils Structuralism Aristotle Lumpers James Frazer, The Golden Bough Splitters Anthropology Mimetic Positivism Chapter 3 Age of Tyrants Pelasgians Tyrannos Indo-Europeans Pisistratus of Athens Proto-Indo-European Attic Ionians Age of Lawgivers Athens Solon Asia Minor Sicily Dorians Black Sea Peloponnese Age of Colonization Trojan War Magna Graecia Epic Phoenicians Homer Lyric Age The Iliad Lyre Heinrich Schliemann Lyric Poetry Troy Sappho Polis Classical Age 1 Chapter 4.1 City Dionysia Thespis Ecstasy Tragoidia "Nothing To Do With Dionysus" Aristotle Year-Spirit The Poetics William Ridgeway Dithyramb Tomb-Theory Bacchylides Hero-Cult Theory Trialogue Gerald Else Dionysus Chapter 4.2 Niches Paleontologists Fitness Charles Darwin Nautilus/Nautiloids Transitional Forms Cultural Darwinism Gradualism Pisistratus Steven Jay Gould City Dionysia Punctuated Equilibrium Annual Trading Season Terms to Know From Section 2: Chapter 5 Sparta Pisistratus Peloponnesian War Athens Post-Classical Age Classical Age Macedon(ia) Persian Wars Barbarian Pericles Philip -

The Development of Tragedy in Ancient Greece Marsha D. Wiese

Fiske Hall Graduate Paper Award What's All the Drama About?: The Development of Tragedy in Ancient Greece Marsha D. Wiese The art of storytelling is only a step away from the art of performance. Yet it took centuries to develop into the form we easily recognize today. Theatre, a gift of ancient Greece, pulled threads from many facets of Greek society -religion, festival, poetry, and competition. And yet, as much as historians know about the Greek theatre, they are still theorizing about its origins and how it suddenly developed and flourished within the confines of the 5th century B.C. Fascination concerning the origin of the theatre developed as quickly as the 4'h century B.C. and remains a topic of speculation even today. Many simply state that drama and tragedy developed out of the cult of Dionysus and the dithyramb, certainly ignoring other important factors of its development. As this paper will argue, during the 7•h and 6th centuries B.C. epic poetry and hero worship intersected with the cult of Dionysus and the dithyramb. This collision of cult worship and poetic art created the high drama of the tragedy found in the late 6th century B.C. and throughout the 5•h century B.C. Therefore, the cult of Dionysus and the dithyramb merely served as catalysts in creating tragic drama and were not its origin. It was during this collision of poetry and religion that tragedy flourished; however, by the 4th century B.C., theatre had moved away from its original religious context to a more political context, shifting the theatre away from tragedy and towards comedy. -

It's Role in Greek Society

The Development of Greek Theatre And It’s Role in Greek Society Egyptian Drama • Ancient Egyptians first to write drama. •King Menes (Narmer) of the 32 nd C. BC. •1st dramatic text along mans’s history on earth. •This text called,”the Memphis drama”. •Memphis; Egypt’s capital King Memes( Narmer) King Menes EGYPT King Menes unites Lower and Upper Egypt into one great 30 civilization. Menes 00 was the first Pharaoh. B The Egyptian civilization was a C great civilization that lasted for about 3,000 years. FROM EGYPT TO GREECE •8500 BC: Primitive tribal dance and ritual. •3100 BC: Egyption coronation play. •2750 BC: Egyption Ritual dramas. •2500 BC: Shamanism ritual. •1887 BC: Passion Play of Abydos. •800 BC: Dramatic Dance •600 BC: Myth and Storytelling: Greek Theatre starts. THE ROLE OF THEATRE IN ANCIENT SOCIETY This is about the way theatre was received and the influence it had. The question is of the place given To theatre by ancient society, the place it had in people ’s lives. The use to which theatre was put at this period was new. “Theatre became an identifier of Greeks as compared to foreigners and a setting in which Greeks emphasized their common identity. Small wonder that Alexander staged a major theatrical event in Tyre in 331 BC and it must have been an act calculated in these terms. It could hardly have meaning for the local population. From there, theatre became a reference point throughout the remainder of antiquity ”. (J.R. Green) Tyre Tyre (Latin Tyrus; Hebrew Zor ), the most important city of ancient Phoenicia, located at the site of present-day Sûr in southern Lebanon. -

Illinois Classical Studies

23 Later Euripidean Music ERIC CSAPO In memory of Desmond Conacher, a much-loved teacher, colleague, andfriend. I. The Scholarship In the last two decades of the twentieth century several important general books marked a resurgence of interest in Greek music: Barker 1984 and 1989, Comotti 1989a (an expanded English translation of a work in Italian written in 1979), M. L. West 1992, W. D. Anderson 1994, Neubecker 1994 (second edition of a work of 1977), and Landels 1999. These volumes provide good general guides to the subject, with particular strengths in ancient theory and practice, the history of musical genres, technical innovations, the reconstruction and use of ancient instruments, ancient musical notation, documents, metrics, and reconstructions of ancient scales, modes, and genera. They are too broadly focussed to give much attention to tragedy. Euripidean music receives no more than three pages in any of these works (a little more is usually allocated to specific discussion of the musical fragment of Orestes). Fewer books were devoted to music in drama. Even stretching back another decade, we have: one general book on tragic music, Pintacuda 1978, two books by Scott on "musical design" in Aeschylus (1984) and in Sophocles (1996), and two books devoted to Aristophanes' music, Pintacuda 1982 and L. P. E. Parker 1997. Pintacuda 1978 offers three chapters on basic background, and one chapter for each of the poets. The chapter on Euripides (shared with a fairly standard account of the New Musicians), contains less than four pages of general discussion of Euripides' relationship to the New Music (164-68), which is followed by fifty pages of blow-by-blow description of the musical numbers in each play—a mildly caffeinated catalogue-style already familiar from Webster 1970b: 110-92 and revisited by Scott. -

Ancient Greek Art Teacher Resource

Image Essay #2 Beak-Spouted Jug ca. 1425 B.C. Mycenaean Glazed ceramic Height: 10 1/4” WAM Accession Number: 48.2098 LOOKING AT THE OBJECT WITH STUDENTS This terracotta clay jug with a long beak-like spout is decorated in light-colored glaze with a series of nautilus- inspired shell patterns. The abstract design on the belly of the jug alludes to a sea creature’s tentacles spreading across the vase emphasizing the shape and volume of the vessel. A wavy leaf design on the vase’s shoulder fur- ther accentuates the marine-motif, with the curves of the leaves referring to the waves of the sea. Around the han- dle and spout are contour lines rendered in brown glaze. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Long before Classical Greece flourished in the 5th century B.C., two major civilizations dominated the Aegean in the 3rd and 2nd millennia B.C.: the Minoans on Crete and the Mycenaeans on the Greek mainland. The prosper- ous Minoans, named after the legendary King Minos, ruled over the sea and built rich palaces on Crete. Their art is characterized by lively scenes depicting fanciful plants and (sea) animals. By the middle of the 2nd millennium B.C., Mycenaean culture started to dominate the Aegean. It is known for its mighty citadels at Mycenae and else- where, its impressive stone tombs, and its extensive trading throughout the Mediterranean world. Beak-spouted jugs were popular in both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures. They held wine or water, and were often placed in tombs as gifts to the deceased. -

Greek Hymns Selected Cult Songs from the Archaic to the Hellenistic

Greek Hymns Selected Cult Songs from the Archaic to the Hellenistic period Part One: The texts in translation William D. Furley and Jan Maarten Bremer Figure 1: Apollo and Artemis, with Hermes (left) and Leto (right). Rf volute krater, possibly by Palermo Painter. J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California. 415-410 BC. Contents Preface . ............................ IX List of Illustrations . ......................XIX List of Abbreviations . ......................XXI Introduction 1 1 The nature of Greek hymns ................. 1 1.1 What is a hymn? . ................. 1 1.2 Ancient theory . ................. 8 1.3 Cult song ...................... 14 1.4 Performance . ................. 20 1.5 Cult song and Pan-Hellenic festival . ...... 35 2 A survey of the extant remains ............... 40 2.1 The Homeric Hymns ................ 41 2.2 Lyric monody . ................. 43 2.3 Choral lyric ..................... 44 2.4 Callimachus . ................. 45 2.5 Philosophical and allegorical hymns . ...... 47 2.6 Magical hymns . ................. 47 2.7 Prose hymns . ................. 48 2.8 The Orphic Hymns and Proklos .......... 49 3 Form and composition . ................. 50 3.1 Invocation ...................... 52 3.2 Praise . ...................... 56 3.3 Prayer . ...................... 60 3.4 An example ..................... 63 1 Crete 65 1.1 A Cretan hymn to Zeus of Mt. Dikta . ........... 68 XIV Contents 2 Delphi 77 Theory of the Paian ..................... 84 Early Delphic Hymns . ................. 91 Delphic mythical tradition ................. 93 2.1 Alkaios’ paian to Apollo . ................. 99 2.2 Pindar’s 6th paian ......................102 2.3 Aristonoos’ hymn to Hestia .................116 2.4 Aristonoos’ paian to Apollo .................119 2.5 Philodamos’ paian to Dionysos . ............121 2.6 Two paians to Apollo with musical notation . ......129 2.6.1 ?Athenaios’ paian and prosodion to Apollo . -

Motherhood and Madness in Dionysian Myth: Something to Do with Demeter (And Dithyramb)

Motherhood and Madness in Dionysian Myth: Something to do with Demeter (and Dithyramb) The most ubiquitous motif of Dionysian myth is when the god drives a person or community mad, and such stories frequently adhere to the so-called "resistance myth" pattern (Seaford 1996:26), where the madness induced by the god is a consequence of the community's rejection of his divinity. This madness frequently results in mothers killing their own children (Seaford 1994:254–7), the most famous example of which is Agave's slaughter of Pentheus in Euripides' Bacchae (E.Bacch.1114ff.). Although the close association between mothers and Dionysian madness was certainly facilitated by a number of cultural factors, in this paper I will discuss one of these factors that has in my view been under-explored: the close connection between Dionysus and mother goddesses, especially Demeter, in myth and cult. The association between Dionysus and Demeter has long been recognized in the literature (exx. Graf 1974:40–78 and Burkert 1983:279, n. 23). Although they were connected through their association with essential crops, grain and the grape, they become symbolically associated with fertility and rebirth; in Demeter's case, this symbolism is realized in her connection with motherhood and the harvest, and for Dionysus in his own death and rebirth. Beyond this shared symbolism, there are key motifs found in myths about Dionysus and Demeter that provide insight into the prevalence of "mad mothers" in Dionysian myth. The most interesting of these motifs is when a mother kills her child specifically by cooking him, as in the Demophoon episode from the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (HH 2.234–48), where Demeter, acting as Demophoon's nurse, roasts him in the fire to render him immortal.