Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; Proquest Pg

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; ProQuest pg. 387 The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus N. G. L. Hammond TUDENTS of ancient history sometimes fall into the error of read Sing their history backwards. They assume that the features of a fully developed institution were already there in its earliest form. Something similar seems to have happened recently in the study of the early Attic theatre. Thus T. B. L. Webster introduces his excellent list of monuments illustrating tragedy and satyr-play with the following sentences: "Nothing, except the remains of the old Dionysos temple, helps us to envisage the earliest tragic background. The references to the plays of Aeschylus are to the lines of the Loeb edition. I am most grateful to G. S. Kirk, H. D. F. Kitto, D. W. Lucas, F. H. Sandbach, B. A. Sparkes and Homer Thompson for their criticisms, which have contributed greatly to the final form of this article. The students of the Classical Society at Bristol produce a Greek play each year, and on one occasion they combined with the boys of Bristol Grammar School and the Cathedral School to produce Aeschylus' Oresteia; they have made me think about the problems of staging. The following abbreviations are used: AAG: The Athenian Agora, a Guide to the Excavation and Museum! (Athens 1962). ARNon, Conventions: P. D. Arnott, Greek Scenic Conventions in the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford 1962). BIEBER, History: M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre2 (Princeton 1961). -

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou ACCHYLIDES 17, a Cean commission performed on Delos, has been the subject of extensive study and is Bmuch admired for its narrative artistry, elegance, and excellence. The ode was classified as a dithyramb by the Alex- andrians, but the Du-Stil address to Apollo in the closing lines renders this classification problematic and has rather baffled scholars. The solution to the thorny issue of the ode’s generic taxonomy is not yet conclusive, and the dilemma paean/ dithyramb is still alive.1 In fact, scholars now are more inclined to place the poem somewhere in the middle, on the premise that in antiquity the boundaries between dithyramb and paean were not so clear-cut as we tend to believe.2 Even though I am 1 Paean: R. Merkelbach, “Der Theseus des Bakchylides,” ZPE 12 (1973) 56–62; L. Käppel, Paian: Studien zur Geschichte einer Gattung (Berlin 1992) 156– 158, 184–189; H. Maehler, Die Lieder des Bakchylides II (Leiden 1997) 167– 168, and Bacchylides. A Selection (Cambridge 2004) 172–173; I. Rutherford, Pindar’s Paeans (Oxford 2001) 35–36, 73. Dithyramb: D. Gerber, “The Gifts of Aphrodite (Bacchylides 17.10),” Phoenix 19 (1965) 212–213; G. Pieper, “The Conflict of Character in Bacchylides 17,” TAPA 103 (1972) 393–404. D. Schmidt, “Bacchylides 17: Paean or Dithyramb?” Hermes 118 (1990) 18– 31, at 28–29, proposes that Ode 17 was actually an hyporcheme. 2 B. Zimmermann, Dithyrambos: Geschichte einer Gattung (Hypomnemata 98 [1992]) 91–93, argues that Ode 17 was a dithyramb for Apollo; see also C. -

The Form of the Orchestra in the Early Greek Theater

THE FORM OF THE ORCHESTRA IN THE EARLY GREEK THEATER (PLATE 89) T HE "orchestra" was essentially a dancing place as the name implies.' The word is generally used of the space between the seats and the scene-building in the ancient theater. In a few theaters of a developed, monumental type, such as at Epidauros (built no earlier than 300 B.C.), the orchestra is defined by a white marble curb which forms a complete circle.2 It is from this beautiful theater, known since 1881, and from the idea of a chorus dancing in a circle around an altar, that the notion of the orchestra as a circular dancing place grew.3 It is not surprising then that W. D6rpfeld expected to find an original orchestra circle when he conducted excavations in the theater of Dionysos at Athens in 1886. The remains on which he based his conclusions were published ten years later in his great work on the Greek theater, which included plans and descriptions of eleven other theaters. On the plan of every theater an orchestra circle is restored, although only at Epidauros does it actually exist. The last ninety years have produced a long bibliography about the form of the theater of Dionysos in its various periods and about the dates of those periods, and much work has been done in the field to uncover other theaters.4 But in all the exam- 1 opXeaat, to dance. Nouns ending in -arrpa signify a place in which some specific activity takes place. See C. D. Buck and W. -

The Acropolis Museum: Contextual Contradictions, Conceptual Complexities by Ersi Filippopoulou

The Acropolis Museum: Contextual Contradictions, Conceptual Complexities by Ersi Filippopoulou 20 | MUSEUM international rsi Filippopoulou is an architect and a jurist, specialised in archaeological museums planning and programming. She served as Director Eof Museum Studies in the Greek Ministry of Culture, and was also responsible for the new Acropolis museum project over 18 years. She worked as Director of the Greek Managing Authority for the European Union, co-financed cultural projects for six years. She served as an adjunct faculty member at the Departments of Architecture of the Universities of Thessaloniki and Patras, Greece. She was elected chairperson of the ICOM International Committee for Architecture and Museum Techniques (ICAMT) twice on a three-year mandate. Since 2012, she has been working as an advisor on heritage issues to the Peloponnese Regional Governor. She recently published a book entitled Τo neo Mouseio tis Acropolis—dia Pyros kai Sidirou, which retraces the new Acropolis Museum’s tumultuous history from its inception to its inauguration (Papasotiriou Publishers 2011). Her current research project is a comparative approach to the Greek archaeological museum paradigm. MUSEUM international | 21 he visitor to the new Acropolis Museum in Athens, climbing to the up- per floor and passing through the exhibition gallery door to an all-glass space flooded with natural light, is suddenly awestruck by the breathtak- ing view of the Parthenon rising up above the surrounding city (Fig. 1). Enjoying the holistic experience inspired by the natural and cultural landscape, the viewer is unaware of past controversies about the mu- seum’s location, and is certain that is the right place to be for anyone wishing to admire the ancient monument together with its architectur- al sculptures. -

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle Much recent work has enhanced our understanding of dithyramb’s identity as a “circular chorus,” primarily by clarifying the ancient use of the phrase “circular chorus” as a label for dithyramb (Käppel 2000; Fearn 2007, ch. 3; Ceccarelli 2013; D’Alessio 2013). Little of that work, however, has investigated the meaning of the phrase “circular chorus,” which is most often assumed to refer to dithyramb’s distinctive choreography, whereby the members of a dithyrambic chorus danced while arranged in a circle around a central object (Fearn 2007: 165-7; Ceccarelli 2013: 162; earlier, Pickard-Cambridge 1962: 32 and 1988: 77). In this paper, I examine one of the earliest moments from the literary record of ancient Greece when dithyramb is called a “circular chorus,” the appearance of the dithyrambic poet Cinesias in Aristophanes’ Birds (1373-1409). I argue that when Aristophanes refers to dithyramb as a “circular chorus” here, he evokes not just the genre’s choreography, but also its vocabulary, poetic structure, and modes of expression and thought. In Birds, the poet Cinesias arrives in Cloudcuckooland boasting of the excellence of his “dithyrambs” (τῶν διθυράμβων, 1388) and promoting himself as a “poet of circular choruses” (τὸν κυκλιοδιδάσκαλον, 1403), thus equating the genre of dithyramb with the label “circular chorus.” Scholars have long noted that, upon Cinesias’ entrance, Peisetaerus alludes to circular dancing with his question “Why do you circle your deformed foot here in a circle?” (τί δεῦρο πόδα σὺ κυλλὸν ἀνὰ κύκλον κυκλεῖς;, 1378; cf. Lawler 1950; Sommerstein 1987: 290; Dunbar 1995: 667-8). -

Lecture 05 Greek Architecture Part 2

Readings Pages 54-60, A World History of Architecture, Fazio, Michael, Moffet & Wodehousecopoy Pages 60– 65 Great Architecture of the World ARCH 1121 HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL TECHNOLOGY Photo: Alexander Aptekar © 2009 Gardner Art Through the Ages Classical Greek Architecture 480 – 431BCE: Known as the Classical Period in Greek History Assertion that human intelligence puts man above the rest of nature Architecture began in the service of religion 7th century BCE – 1st efforts to create proper shapes and design Beauty = Gods Secret of beauty lay in ratios and proportions Invented democracy and philosophy Created works of art in drama, sculpture and architecture Greek Architecture 480 – 431BCE Temples first built with wood, then stone w/ terra cotta tiles Purely formal objects Greeks pursued the beauty through architecture and materials The home of the Gods Became the principal ornaments in the cities, generally on hills or other prominent locations www.greatbuildings.com www.greatbuildings.com Temple of Hephaestus megron Athenian Treasury Classical Orders In classical Greek architecture, beauty lay in systems of the ratios and proportions. A system or order defined the ideal proportions for all the components of the temples according to mathematical ratios – based on the diameter of the columns. What is an order? An order includes the total assemblage of parts consisting of the column and its appropriate entablature which is based on the diameter of the column. Temple of Hera II (Poseidon) 450 BCE The column is vertical and supports the structure. Its diameter sets the proportion of the other parts. The entablature is horizontal and consists of many elements. -

Attic Dramamailversion.Pptx

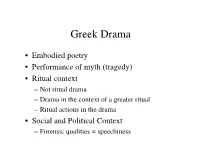

Greek Drama • Embodied poetry • Performance of myth (tragedy) • Ritual context – Not ritual drama – Drama in the context of a greater ritual – Ritual actions in the drama • Social and Political Context – Forensic qualities = speechiness Athenian Dramatic Festivals • The audience: 10-14,000 people, mostly Athenian male citizens, sometimes foreign dignitaries • Poets “applied” for a chorus 6 months before. • Competition during religious festivals for the god Dionysus – City Dionysia (April/March) open to foreign visitors – Lenaia (January) more “closed” to outsiders Performances of: Tragedies (oldest form) (9 plays by 3 tragic poets) Satyr plays (3 plays by the 3 tragic poets) Comedies (1 each by 3 to 5 comic poets) Dithyrambs (10 choruses of men, 10 of boys) Audience saw 4 or 5 plays a day, for three or four days. Tragic mornings, comic afternoons. Other official business was done as well. Evolution of Genres • dithyramb (hymn in honor of Dionysus) • tragedy (diverged from Dionysian themes) – Thespis, 534 BC • satyr play (reinserted Dionysian themes) – included 502-501 BC • Comedy <= from the komos (revelry) ca. 486 BC Origins of Phallic Procession A phallos is a long piece of timber fitted with leather genitalia at the top. The phallos came to be part of the worship of Dionysus by some secret rite. About the phallos itself the following is said. Pegasos took the image of Dionysus from Eleutherai—Eleutherai is a city of Boeotia [a region neighboring Attica, the region of Athens]—and brought it to Attica. The Athenians, however, did not receive the god with reverence, but they did not get away with this resolve unpunished, because, since the god was angry, a disease [priapism?] attacked the men’s genitals and the calamity was incurable. -

Mapping the History of Malaysian Theatre: an Interview with Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof

ASIATIC, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2010 Mapping the History of Malaysian Theatre: An Interview with Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof Madiha Ramlan & M.A. Quayum1 International Islamic University Malaysia It seems that a rich variety of traditional theatre forms existed and perhaps continues to exist in Malaysia. Could you provide some elucidation on this? If you are looking for any kind of history or tradition of theatre in Malaysia you won’t get it, because of its relative antiquity and the lack of records. Indirect sources such as hikayat literature fail to mention anything. Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai mentions Javanese wayang kulit, and Hikayat Patani mentions various music and dance forms, most of which cannot be precisely identified, but there is no mention of theatre. The reason is clear enough. The hikayat generally focuses on events in royal court, while most traditional theatre developed as folk art, with what is known as popular theatre coming in at the end of the 19th century. There has never been any court tradition of theatre in the Malay sultanates. In approaching traditional theatre, my own way has been to first look at the proto- theatre or elementary forms before going on to the more advanced ones. This is a scheme I worked out for traditional Southeast Asian theatre. Could you elaborate on this? Almost all theatre activity in Southeast Asia fits into four categories as follows: Proto-Theatre, Puppet Theatre, Dance Theatre and Opera. In the case of the Philippines, one could identify a separate category for Christian theatre forms. Such forms don’t exist in the rest of the region. -

Study Tour to Greece~

Tour is open to: • All students • Alumnae Trip Highlights~ Enhance your studies at some of the greatest ancient sites in the Study Tour to world. We owe our western view of the world to the modern- thinking Greeks. Theatre and psychology come together in this 10- Greece~ day trip to Athens and Santorini. Daily excursions take us to Delphi, the ancient center of the Earth the Naval Stone, the Parthenon, the With Professor Roxanne Amico and Acropolis, the Agora, Mycene and Epidaurus, Theatre of Dionysus, Lycabettus Hill and wonderful museums. You will enjoy great food Dr. Sharon Himmanen and nightlife in historic Plaka, the location of our hotel at the foot of May 14--May 25, 2017 the Acropolis and some free time in Syntagma Square in Athens, the seaport of Piraeus and the old flea market and shopping area of Course: THS / PSY 260- (1 credit) Monastiraki. Reading lists will be available for all travelers. In the Footsteps of the Ancient Greeks Students seeking course credit will have play readings and writing assignments focused on the relationship between ancient psychology Students are encouraged to take class if and philosophy and Greek drama. participating in travel component. THS / PSY 260 are not “free—standing” Included in Program Fee: classes. o Round Trip shuttle between campus and the airport o International flights to/from Athens Contact: Mary Anne Kucserik o Airport transfers in Athens Director of Global Initiatives & o 8 overnights in twin-shared accommodations in Athens International Programs & 2 overnights in Santorini, with daily breakfast included Curtis 201 o One welcome and one farewell dinner included o Round trip transfer to Santorini to include guided [email protected] cultural visits and entries 610-606-4666, ext. -

History of Theatre the Romans Continued Theatrical Thegreek AD (753 Roman Theatre fi Colosseum Inrome, Which Was Built Between Tradition

History of theatre Ancient Greek theatre Medieval theatre (1000BC–146BC) (900s–1500s) The Ancient Greeks created After the Romans left Britain, theatre purpose-built theatres all but died out. It was reintroduced called amphitheatres. during the 10th century in the form Amphitheatres were usually of religious dramas, plays with morals cut into a hillside, with Roman theatre and ‘mystery’ plays performed in tiered seating surrounding (753BC–AD476) churches, and later outdoors. At a the stage in a semi-circle. time when church services were Most plays were based The Romans continued the Greek theatrical tradition. Their theatres resembled Greek conducted in Latin, plays were on myths and legends, designed to teach Christian stories and often involved a amphitheatres but were built on their own foundations and often enclosed on all sides. The and messages to people who could ‘chorus’ who commented not read. on the action. Actors Colosseum in Rome, which was built between wore masks and used AD72 and AD80, is an example of a traditional grandiose gestures. The Roman theatre. Theatrical events were huge works of famous Greek spectacles and could involve acrobatics, dancing, playwrights, such as fi ghting or a person or animal being killed on Sophocles, Aristophanes stage. Roman actors wore specifi c costumes to and Euripedes, are still represent different types of familiar characters. performed today. WORDS © CHRISTINA BAKER; ILLUSTRATIONS © ROGER WARHAM 2008 PHOTOCOPIABLE 1 www.scholastic.co.uk/junioredplus DECEMBER 2008 Commedia dell’Arte Kabuki theatre (1500s Italy) (1600s –today Japan) Japanese kabuki theatre is famous This form of Italian theatre became for its elaborate costumes and popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. -

Evolution of Street Theatre As a Tool of Political Communication Sangita

Evolution of Street Theatre as a tool of Political Communication Sangita De & Priyam Basu Thakur Abstract In the post Russian Revolution age a distinct form of theatrical performance emerged as a Street Theatre. Street theatre with its political sharpness left a crucial effect among the working class people in many corner of the world with the different political circumstances. In India a paradigm shift from proscenium theatre to the theatre of the streets was initiated by the anti-fascist movement of communist party of India under the canopy of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). In North India Street theatre was flourished by Jana Natya Manch (JANAM) with the leadership of Safdar Hashmi. This paper will explore the background of street theatre in India and its role in political communication with special reference to historical and analytical study of the role of IPTA, JANAM etc. Keywords: Street Theatre, Brecht, Theatre of the Oppressed, Communist Party of India (CPI), IPTA, JANAM, Safdar Hashmi, Utpal Dutta. Introduction Scholars divided the history of theatre forms into the pre-Christian era and Christian era. Aristotle’s view about the structure of theatre was based on Greek tragedy. According to the scholar Alice Lovelace “He conceived of a theatre to carry the world view and moral values of those in power, investing their language and symbols with authority and acceptance. Leaving the masses (parties to the conflict) to take on the passive role of audience...........The people watch and through the emotions of pity & grief, suffer with him.” Bertolt Brecht expressed strong disagreement with the Aristotelian concept of catharsis.