Dithyramb, Tragedy, and the Basel Krater Matthew C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN by Sarah Kellis Jennings Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Theatre Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 3, 2013 ii STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN Project Approved: T.J. Walsh, Ph.D. Department of Theatre (Supervising Professor) Harry Parker, Ph.D. Department of Theatre Kindra Santamaria, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 GREEK THEATRE .............................................................................................................1 The Dithyramb ................................................................................................................2 Grecian Tragedy .............................................................................................................4 The Greek Actor ............................................................................................................. 8 The Satyr Play ................................................................................................................9 The Greek Theatre Structure and Technical Flourishes ...............................................10 Grecian -

The Underworld Krater from Altamura

The Underworld Krater from Altamura The Underworld krater was found in 1847 in Altamura in 1 7 Persephone and Hades Herakles and Kerberos ITALY southeastern Italy. The ancient name of the town is unknown, Hades, ruler of the Underworld, was the brother of Zeus (king of the gods) and Poseidon (god of The most terrifying of Herakles’s twelve labors was to kidnap the guard dog of the Underworld. APULIA Naples but by the fourth century bc it was one of the largest fortified Altamura the sea). He abducted Persephone, daughter of the goddess Demeter, to be his wife and queen. For anyone who attempted to leave the realm of the dead without permission, Kerberos (Latin, Taranto (Taras) m settlements in the region. There is little information about Although Hades eventually agreed to release Persephone, he had tricked her into eating the seeds Cerberus) was a threatening opponent. The poet Hesiod (active about 700 BC) described the e d i t e r of a pomegranate, and so she was required to descend to the Underworld for part of each year. “bronze-voiced” dog as having fifty heads; later texts and depictions give it two or three. r a what else was deposited with the krater, but its scale suggests n e a n Here Persephone sits beside Hades in their palace. s e a that it came from the tomb of a prominent individual whose community had the resources to create and transport such a 2 9 substantial vessel. 2 The Children of Herakles and Megara 8 Woman Riding a Hippocamp Map of southern Italy marking key locations mentioned in this gallery The inhabitants of southeastern Italy—collectively known as The Herakleidai (children of Herakles) and their mother, Megara, are identified by the Greek The young woman riding a creature that is part horse, part fish is a puzzling presence in the Apulians—buried their dead with assemblages of pottery and other goods, and large vessels inscriptions above their heads. -

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou ACCHYLIDES 17, a Cean commission performed on Delos, has been the subject of extensive study and is Bmuch admired for its narrative artistry, elegance, and excellence. The ode was classified as a dithyramb by the Alex- andrians, but the Du-Stil address to Apollo in the closing lines renders this classification problematic and has rather baffled scholars. The solution to the thorny issue of the ode’s generic taxonomy is not yet conclusive, and the dilemma paean/ dithyramb is still alive.1 In fact, scholars now are more inclined to place the poem somewhere in the middle, on the premise that in antiquity the boundaries between dithyramb and paean were not so clear-cut as we tend to believe.2 Even though I am 1 Paean: R. Merkelbach, “Der Theseus des Bakchylides,” ZPE 12 (1973) 56–62; L. Käppel, Paian: Studien zur Geschichte einer Gattung (Berlin 1992) 156– 158, 184–189; H. Maehler, Die Lieder des Bakchylides II (Leiden 1997) 167– 168, and Bacchylides. A Selection (Cambridge 2004) 172–173; I. Rutherford, Pindar’s Paeans (Oxford 2001) 35–36, 73. Dithyramb: D. Gerber, “The Gifts of Aphrodite (Bacchylides 17.10),” Phoenix 19 (1965) 212–213; G. Pieper, “The Conflict of Character in Bacchylides 17,” TAPA 103 (1972) 393–404. D. Schmidt, “Bacchylides 17: Paean or Dithyramb?” Hermes 118 (1990) 18– 31, at 28–29, proposes that Ode 17 was actually an hyporcheme. 2 B. Zimmermann, Dithyrambos: Geschichte einer Gattung (Hypomnemata 98 [1992]) 91–93, argues that Ode 17 was a dithyramb for Apollo; see also C. -

A Masterpiece of Ancient Greece

Press Release A Masterpiece of Ancient Multimedia Greece: a World of Men, Feb. 01 - Sept. 01 2013 Gods, and Heroes DNP, Gotanda Building, Tokyo Louvre - DNP Museum Lab Tenth presentation in Tokyo The tenth Louvre - DNP Museum Lab presentation, which closes the second phase of this partnership between the Louvre and Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd (DNP), invites visitors to discover the art of ancient Greece, a civilization which had a significant impact on Western art and culture. They will be able to admire four works from the Louvre's Greek art collection, and in particular a ceramic masterpiece known as the Krater of Antaeus. This experimental exhibition features a series of original multimedia displays designed to enhance the observation and understanding of Greek artworks. Three of the displays designed for this presentation are scheduled for relocation in 2014 to the Louvre in Paris. They will be installed in three rooms of the Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Red-figure calyx krater Signed by the painter Euphronios, attributed to the Antiquities, one of which is currently home to the Venus de Milo. potter Euxitheos. Athens, c. 515–510 BC. Clay The first two phases of this project, conducted over a seven-year Paris, Musée du Louvre. G 103 period, have allowed the Louvre and DNP to explore new © Photo DNP / Philippe Fuzeau approaches to art using digital and imaging technologies; the results have convinced them of the interest of this joint venture, which they now intend to pursue along different lines. Location : Louvre – DNP Museum Lab Ground Floor, DNP - Gotanda 3-5-20 Nishi-Gotanda, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo The "Krater of Antaeus", one of the Louvre's must-see masterpieces, Opening period : provides a perfect illustration of the beauty and quality of Greek Friday February 1 to Sunday September 1, ceramics. -

A Mycenaean Ritual Vase from the Temple at Ayia Irini, Keos

A MYCENAEAN RITUAL VASE FROM THE TEMPLE AT AYIA IRINI, KEOS (PLATE 18) D URING the 1963 excavations of the University of Cincinnatiat Ayia Irini, a number of fragments belonging to a curious and important Mycenaean vase were discovered in the Temple, mostly in Rooms IV and XI where they were found widely scattered in the post-Late Minoan IB earthquake strata.' Since it is impos- sible to date the vase stratigraphically, it is hoped that analysis of its shape and decoration may contribute something to our knowledge of the later history of the Temple in its Mycenaean period. Unfortunately, the vase is so fragmentary and its decoration so unstandardized that this is no simple task. It is the goal of this paper to look critically at the fragments and see what they suggest for the re- construction of the vase, its probable date and affinities, and its function in the Temple. Following two main lines of approach, we will first attempt a reconstruction of the shape and then analyze the pictorial decoration. Both are important in deter- mining date, possible provenience, and function. The fragments fall into three main groups: 1) those coming from the shoulder and upper part of an ovoid closed pot with narrow neck, now made up into two large fragments which do not join but which constitute about one-third the circumference (P1. 18 :a, b, c); 2) at least two fragments from the lower part of a tapering piriform shape (P1. 18 :d, d and e) ; 3) fragments of one or more hollow ring handles (P1. -

Vases and Kalos-Names from an Agora Well

VASES AND KALOS-NAMES FROM AN AGORA WELL A collection of graffiti on vases, found in a well in the Agora during the 1935 campaign,' has provided a fresh grouping of Attic kalos-inscriptions, and has added new names to the list. Our brief inspection of this material falls into three parts: we must consider the few figured pieces found in the well, the inscriptions as such, and the shapes of the vases, plain black-glazed and unglazed, on and in connection with which the inscriptions appear. The black-glazed table wares and substantial household furnishings with which the well was filled had only three figured companions. Of these the most interesting is illustrated in Figure 1. Preserved is more than half of one side of a double-disk, or bobbin.2 On it, Helios rising in his chariot drawn by winged white horses, is about to crest the sun-tipped waves. This theme, familiar from black-figured lekythoi, here finds its most elaborate expression. Our composition refines upon the solidity and power of the Brygos painter's Selene,3 to which it is most nearly related. The delicately curving wings of the horses, echoing the rim-circle, provide a second frame for the figlure of the god. Beneath the horses, all is tumult. Wave upon wave seems ready to engulf so dainty a team. But above, remote from confusions, stands the charioteer, confident and serene, his divine nature indicated by the great disk of the sun lightly poised upon his head. The contest between natural forces and the divine is a well-loved theme of Greek art; but it is rare to find, as liere, an element and not its personification. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle Much recent work has enhanced our understanding of dithyramb’s identity as a “circular chorus,” primarily by clarifying the ancient use of the phrase “circular chorus” as a label for dithyramb (Käppel 2000; Fearn 2007, ch. 3; Ceccarelli 2013; D’Alessio 2013). Little of that work, however, has investigated the meaning of the phrase “circular chorus,” which is most often assumed to refer to dithyramb’s distinctive choreography, whereby the members of a dithyrambic chorus danced while arranged in a circle around a central object (Fearn 2007: 165-7; Ceccarelli 2013: 162; earlier, Pickard-Cambridge 1962: 32 and 1988: 77). In this paper, I examine one of the earliest moments from the literary record of ancient Greece when dithyramb is called a “circular chorus,” the appearance of the dithyrambic poet Cinesias in Aristophanes’ Birds (1373-1409). I argue that when Aristophanes refers to dithyramb as a “circular chorus” here, he evokes not just the genre’s choreography, but also its vocabulary, poetic structure, and modes of expression and thought. In Birds, the poet Cinesias arrives in Cloudcuckooland boasting of the excellence of his “dithyrambs” (τῶν διθυράμβων, 1388) and promoting himself as a “poet of circular choruses” (τὸν κυκλιοδιδάσκαλον, 1403), thus equating the genre of dithyramb with the label “circular chorus.” Scholars have long noted that, upon Cinesias’ entrance, Peisetaerus alludes to circular dancing with his question “Why do you circle your deformed foot here in a circle?” (τί δεῦρο πόδα σὺ κυλλὸν ἀνὰ κύκλον κυκλεῖς;, 1378; cf. Lawler 1950; Sommerstein 1987: 290; Dunbar 1995: 667-8). -

Serious Drinking: Vases of the Greek Symposium

SERIOUS DRINKING: Vases of the Greek Symposium “Drink with me, play music with me, love with me, wear a crown with me, be mad with me when I am mad and wise when I am wise.” - Athenaeus The ancient Greek symposium (from the setting. In studying side A of this 4th century Greek symposion) was a highly choreographed, B.C. vase, one can readily observe a symposi- Serious Drinking: Vases of all-male drinking party that often drew ast’s idealized version of himself in the heroic the Greek Symposium has to a close with a riotous parade about the soldiers taking leave of their women. The been organized collaboratively shuttered streets of town. Wine, and the soldiers, like the drinkers, depart from female by Susan Rotroff, professor in temporary self-abandonment it offered, was society to participate in decidedly male action. the Department of Classics and the chief ingredient of these gatherings; yet The symposium is the peaceful inverse of the Department of Art History intoxication was not the party’s sum intent. battle; both define the society, one in fostering and Archaeology; Grizelda Certain rules were devised under the auspices community and the other in defending it. The McClelland, PhD candidate in of a designated leader, the symposiarch or ban- krater itself is emblematic of the symposium’s the Department of Classics and quet master, who regulated the socializing communal ideals. Its physical placement the Department of Art History of his guests. It was he who set the tenor of at the center of the room is analogous to its and Archaeology; and Emily the party, defining how much wine was to be function. -

Download Circe and Odysseus in Ancient

Circe and Odysseus in Ancient Art This resource offers a series of questions that will help students engage with four ancient artifacts that represent the goddess Circes interactions or influences upon Odysseus and his companions. All these artifacts were made several centuries after the Odyssey was composed, but they should not be approached as straightforward or mere illustrations of episodes from the Odyssey. Rather, all five works of art (four artifacts and the epic poem) represent different versions of the story of how Circe interacts with Odysseus and his men. This resource assumes that students already will have read Books 9 and 10 of the Odyssey. This handout is formatted as a guide that an instructor can use to facilitate a conversation during a class meeting. The questions are meant to be asked by the instructor while students actively look at images of each artifact, using the weblinks provided. After each question, examples of possible observations that students might offer are included in italics. The italicized answers also sometimes include extra information that the instructor can share. Artifact #1: A kylix (drinking cup) at the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston) Attributed to the Painter of the Boston Polyphemos Made in Athens (Attica, Greece) ca. 550-525 BCE https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153469/drinking-cup-kylix-depicting-scenes-from-the- odyssey;jsessionid=31E168DC9A32CBB824DCBBFFA1671DC1?ctx=bb1a3a19-ebc8-46ce-b9b1- 03dc137d5b86&idx=1 Accession number 99.518 1. We are going to look at both sides of this kylix, but we will begin with the first image on the website (“Side A” of the kylix, which does not include anyone holding a shield). -

Attic Dramamailversion.Pptx

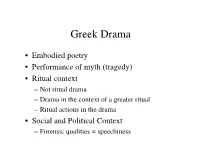

Greek Drama • Embodied poetry • Performance of myth (tragedy) • Ritual context – Not ritual drama – Drama in the context of a greater ritual – Ritual actions in the drama • Social and Political Context – Forensic qualities = speechiness Athenian Dramatic Festivals • The audience: 10-14,000 people, mostly Athenian male citizens, sometimes foreign dignitaries • Poets “applied” for a chorus 6 months before. • Competition during religious festivals for the god Dionysus – City Dionysia (April/March) open to foreign visitors – Lenaia (January) more “closed” to outsiders Performances of: Tragedies (oldest form) (9 plays by 3 tragic poets) Satyr plays (3 plays by the 3 tragic poets) Comedies (1 each by 3 to 5 comic poets) Dithyrambs (10 choruses of men, 10 of boys) Audience saw 4 or 5 plays a day, for three or four days. Tragic mornings, comic afternoons. Other official business was done as well. Evolution of Genres • dithyramb (hymn in honor of Dionysus) • tragedy (diverged from Dionysian themes) – Thespis, 534 BC • satyr play (reinserted Dionysian themes) – included 502-501 BC • Comedy <= from the komos (revelry) ca. 486 BC Origins of Phallic Procession A phallos is a long piece of timber fitted with leather genitalia at the top. The phallos came to be part of the worship of Dionysus by some secret rite. About the phallos itself the following is said. Pegasos took the image of Dionysus from Eleutherai—Eleutherai is a city of Boeotia [a region neighboring Attica, the region of Athens]—and brought it to Attica. The Athenians, however, did not receive the god with reverence, but they did not get away with this resolve unpunished, because, since the god was angry, a disease [priapism?] attacked the men’s genitals and the calamity was incurable. -

Pindar Fr. 75 SM and the Politics of Athenian Space Richard T

Pindar Fr. 75 SM and the Politics of Athenian Space Richard T. Neer and Leslie Kurke Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow. Anne Carson, “The Life of Towns” T IS WELL KNOWN that Pindar’s poems were occasional— composed on commission for specific performance settings. IBut they were also, we contend, situational: mutually im- plicated with particular landscapes, buildings, and material artifacts. Pindar makes constant reference to precious objects and products of craft, both real and metaphorical; he differs, in this regard, from his contemporary Bacchylides. For this reason, Pindar provides a rich phenomenology of viewing, an insider’s perspective on the embodied experience of moving through a built environment amidst statues, buildings, and other monu- ments. Analysis of the poetic text in tandem with the material record makes it possible to reconstruct phenomenologies of sculpture, architecture, and landscape. Our example in this essay is Pindar’s fragment 75 SM and its immediate context: the cityscape of early Classical Athens. Our hope is that putting these two domains of evidence together will shed new light on both—the poem will help us solve problems in the archaeo- logical record, and conversely, the archaeological record will help us solve problems in the poem. Ultimately, our argument will be less about political history, and more about the ordering of bodies in space, as this is mediated or constructed by Pindar’s poetic sophia. This is to attend to the way Pindar works in three dimensions, as it were, to produce meaningful relations amongst entities in the world.1 1 Interest in Pindar and his material context has burgeoned in recent ————— Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 54 (2014) 527–579 2014 Richard T.