Motherhood and Madness in Dionysian Myth: Something to Do with Demeter (And Dithyramb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demeter and Dionysos: Connections in Literature, Cult and Iconography Kathryn Cook April 2011

Demeter and Dionysos: Connections in Literature, Cult and Iconography Kathryn Cook April 2011 Demeter and Dionysos are two gods among the Greek pantheon who are not often paired up by modern scholars; however, evidence from a number of sources alluding to myth, cult and iconography shows that there are similarities and connections observable from our present point of view, that were commented upon by contemporary authors. This paper attempts to examine the similarities and connections between Demeter and Dionysos up through the Classical period. These two deities were not always entwined in myth. Early evidence of gods in the Linear B tablets mention Dionysos as the name of a deity, but Demeter’s name does not appear in the records until later. Over the centuries (up to approximately the 6th century as mentioned in this paper), Demeter and Dionysos seem to have been depicted together in cult and in literature more and more often. In particular, the figure of Iacchos in the Eleusinian cult seems to form a bridging element between the two which grew from being a personification of the procession for Demeter, into being a Dionysos figure who participated in her cult. Literature: Demeter and Dionysos have some interesting parallels in literature. To begin with, they are both rarely mentioned in the Homeric poems, compared to other gods like Hera or Athena. In the Iliad, neither Demeter nor Dionysos plays a role as a main character. Instead they are mentioned in passing, as an example or as an element of an epic simile.1 These two divine figures are present even less often in the Odyssey, though this is perhaps a reflection of the fewer appearances of the gods overall, they are 1 Demeter: 2.696. -

Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN by Sarah Kellis Jennings Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Theatre Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 3, 2013 ii STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN Project Approved: T.J. Walsh, Ph.D. Department of Theatre (Supervising Professor) Harry Parker, Ph.D. Department of Theatre Kindra Santamaria, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 GREEK THEATRE .............................................................................................................1 The Dithyramb ................................................................................................................2 Grecian Tragedy .............................................................................................................4 The Greek Actor ............................................................................................................. 8 The Satyr Play ................................................................................................................9 The Greek Theatre Structure and Technical Flourishes ...............................................10 Grecian -

Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2009 A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. "A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' 'Orphic' Creation of Mankind." American Journal of Philology 130, no. 4 (2009): 511-532. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radcliffe G. Edmonds III “A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' ‘Orphic’ Creation of Mankind” American Journal of Philology 130 (2009), pp. 511–532. A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' Creation of Mankind Olympiodorus' recounting (In Plat. Phaed. I.3-6) of the Titan's dismemberment of Dionysus and the subsequent creation of humankind has served for over a century as the linchpin of the reconstructions of the supposed Orphic doctrine of original sin. From Comparetti's first statement of the idea in his 1879 discussion of the gold tablets from Thurii, Olympiodorus' brief testimony has been the -

Greek Characters

Amphitrite - Wife to Poseidon and a water nymph. Poseidon - God of the sea and son to Cronos and Rhea. The Trident is his symbol. Arachne - Lost a weaving contest to Athene and was turned into a spider. Father was a dyer of wool. Athene - Goddess of wisdom. Daughter of Zeus who came out of Zeus’s head. Eros - Son of Aphrodite who’s Roman name is Cupid; Shoots arrows to make people fall in love. Demeter - Goddess of the harvest and fertility. Daughter of Cronos and Rhea. Hades - Ruler of the underworld, Tartaros. Son of Cronos and Rhea. Brother to Zeus and Poseidon. Hermes - God of commerce, patron of liars, thieves, gamblers, and travelers. The messenger god. Persephone - Daughter of Demeter. Painted the flowers of the field and was taken to the underworld by Hades. Daedalus - Greece’s greatest inventor and architect. Built the Labyrinth to house the Minotaur. Created wings to fly off the island of Crete. Icarus - Flew too high to the sun after being warned and died in the sea which was named after him. Son of Daedalus. Oranos - Titan of the Sky. Son of Gaia and father to Cronos. Aphrodite - Born from the foam of Oceanus and the blood of Oranos. She’s the goddess of Love and beauty. Prometheus - Known as mankind’s first friend. Was tied to a Mountain and liver eaten forever. Son of Oranos and Gaia. Gave fire and taught men how to hunt. Apollo - God of the sun and also medicine, gold, and music. Son of Zeus and Leto. Baucis - Old peasant woman entertained Zeus and Hermes. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed. -

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou ACCHYLIDES 17, a Cean commission performed on Delos, has been the subject of extensive study and is Bmuch admired for its narrative artistry, elegance, and excellence. The ode was classified as a dithyramb by the Alex- andrians, but the Du-Stil address to Apollo in the closing lines renders this classification problematic and has rather baffled scholars. The solution to the thorny issue of the ode’s generic taxonomy is not yet conclusive, and the dilemma paean/ dithyramb is still alive.1 In fact, scholars now are more inclined to place the poem somewhere in the middle, on the premise that in antiquity the boundaries between dithyramb and paean were not so clear-cut as we tend to believe.2 Even though I am 1 Paean: R. Merkelbach, “Der Theseus des Bakchylides,” ZPE 12 (1973) 56–62; L. Käppel, Paian: Studien zur Geschichte einer Gattung (Berlin 1992) 156– 158, 184–189; H. Maehler, Die Lieder des Bakchylides II (Leiden 1997) 167– 168, and Bacchylides. A Selection (Cambridge 2004) 172–173; I. Rutherford, Pindar’s Paeans (Oxford 2001) 35–36, 73. Dithyramb: D. Gerber, “The Gifts of Aphrodite (Bacchylides 17.10),” Phoenix 19 (1965) 212–213; G. Pieper, “The Conflict of Character in Bacchylides 17,” TAPA 103 (1972) 393–404. D. Schmidt, “Bacchylides 17: Paean or Dithyramb?” Hermes 118 (1990) 18– 31, at 28–29, proposes that Ode 17 was actually an hyporcheme. 2 B. Zimmermann, Dithyrambos: Geschichte einer Gattung (Hypomnemata 98 [1992]) 91–93, argues that Ode 17 was a dithyramb for Apollo; see also C. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus

Alana Koontz The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus Alana Koontz is a student at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee graduating with a degree in Art History and a certificate in Ancient Mediterranean Studies. The main focus of her studies has been ancient art, with specific attention to ancient architecture, statuary, and erotic symbolism in ancient art. Through various internships, volunteering and presentations, Alana has deepened her understanding of the art world, and hopes to do so more in the future. Alana hopes to continue to grad school and earn her Master’s Degree in Art History and Museum Studies, and eventually earn her PhD. Her goal is to work in a large museum as a curator of the ancient collections. Alana would like to thank the Religious Studies Student Organization for this fantastic experience, and appreciates them for letting her participate. Dionysus was the god of wine, art, vegetation and also widely worshipped as a fertility god. The cult of Dionysus worshipped him fondly with cultural festivities, wine-induced ritualistic dances, 1 intense and violent orgies, and secretive various depictions of drunken revelry. 2 He embodies the intoxicating portion of nature. Dionysus, in myth, was the last god to be accepted at Mt Olympus, and was known for having a mortal mother. He spent his adulthood teaching the cultivation of grapes, and wine-making. The worship began as a celebration of culture, with plays and processions, and progressed into a cult that was shrouded in mystery. Later in history, worshippers would perform their rituals in the cover of darkness, limiting the cult-practitioners to women, and were surrounded by myth that is sometimes interpreted as fact. -

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle

Aristophanes and the Definition of Dithyramb: Moving Beyond the Circle Much recent work has enhanced our understanding of dithyramb’s identity as a “circular chorus,” primarily by clarifying the ancient use of the phrase “circular chorus” as a label for dithyramb (Käppel 2000; Fearn 2007, ch. 3; Ceccarelli 2013; D’Alessio 2013). Little of that work, however, has investigated the meaning of the phrase “circular chorus,” which is most often assumed to refer to dithyramb’s distinctive choreography, whereby the members of a dithyrambic chorus danced while arranged in a circle around a central object (Fearn 2007: 165-7; Ceccarelli 2013: 162; earlier, Pickard-Cambridge 1962: 32 and 1988: 77). In this paper, I examine one of the earliest moments from the literary record of ancient Greece when dithyramb is called a “circular chorus,” the appearance of the dithyrambic poet Cinesias in Aristophanes’ Birds (1373-1409). I argue that when Aristophanes refers to dithyramb as a “circular chorus” here, he evokes not just the genre’s choreography, but also its vocabulary, poetic structure, and modes of expression and thought. In Birds, the poet Cinesias arrives in Cloudcuckooland boasting of the excellence of his “dithyrambs” (τῶν διθυράμβων, 1388) and promoting himself as a “poet of circular choruses” (τὸν κυκλιοδιδάσκαλον, 1403), thus equating the genre of dithyramb with the label “circular chorus.” Scholars have long noted that, upon Cinesias’ entrance, Peisetaerus alludes to circular dancing with his question “Why do you circle your deformed foot here in a circle?” (τί δεῦρο πόδα σὺ κυλλὸν ἀνὰ κύκλον κυκλεῖς;, 1378; cf. Lawler 1950; Sommerstein 1987: 290; Dunbar 1995: 667-8). -

THE ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES of DEMETER and PERSEPHONE: Fertility, Sexuality, Ancl Rebirth Mara Lynn Keller

THE ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES OF DEMETER AND PERSEPHONE: Fertility, Sexuality, ancl Rebirth Mara Lynn Keller The story of Demeter and Persephone, mother and daugher naturc goddesses, provides us with insights into the core beliefs by which earl) agrarian peoples of the Mediterranean related to “the creative forces of thc universe”-which some people call God, or Goddess.’ The rites of Demetei and Persephone speak to the experiences of life that remain through all time< the most mysterious-birth, sexuality, death-and also to the greatest niys tery of all, enduring love. In these ceremonies, women and inen expressec joy in the beauty and abundance of nature, especially the bountiful harvest in personal love, sexuality and procreation; and in the rebirth of the humail spirit, even through suffering and death. Cicero wrote of these rites: “Wc have been given a reason not only to live in joy, but also to die with bettei hope. ”2 The Mother Earth religion ceIebrated her children’s birth, enjoyment of life and loving return to her in death. The Earth both nourished the living and welcomed back into her body the dead. As Aeschylus wrote in TIic Libation Bearers: Yea, summon Earth, who brings all things to life and rears, and takes again into her womb.3 I wish to express my gratitude for the love and wisdom of my mother, hlary 1’. Keller, and of Dr. Muriel Chapman. They have been invaluable soiirces of insight and under- standing for me in these studies. So also have been the scholarship, vision atdot- friendship of Carol €! Christ, Charlene Spretnak, Deem Metzger, Carol Lee Saiichez, Ruby Rohrlich, Starhawk, Jane Ellen Harrison, Kiane Eisler, Alexis Masters, Richard Trapp, John Glanville, Judith Plaskow, Jim Syfers, Jim Moses, Bonnie blacCregor and Lil Moed. -

Athena ΑΘΗΝΑ Zeus ΖΕΥΣ Poseidon ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ Hades ΑΙΔΗΣ

gods ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝ ΑΡΤΕΜΙΣ ΑΘΗΝΑ ΔΙΟΝΥΣΟΣ Athena Greek name Apollo Artemis Minerva Roman name Dionysus Diana Bacchus The god of music, poetry, The goddess of nature The goddess of wisdom, The god of wine and art, and of the sun and the hunt the crafts, and military strategy and of the theater Olympian Son of Zeus by Semele ΕΡΜΗΣ gods Twin children ΗΦΑΙΣΤΟΣ Hermes of Zeus by Zeus swallowed his first Mercury Leto, born wife, Metis, and as a on Delos result Athena was born ΑΡΗΣ Hephaestos The messenger of the gods, full-grown from Vulcan and the god of boundaries Son of Zeus the head of Zeus. Ares by Maia, a Mars The god of the forge who must spend daughter The god and of artisans part of each year in of Atlas of war Persephone the underworld as the consort of Hades ΑΙΔΗΣ ΖΕΥΣ ΕΣΤΙΑ ΔΗΜΗΤΗΡ Zeus ΗΡΑ ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ Hades Jupiter Hera Poseidon Hestia Pluto Demeter The king of the gods, Juno Vesta Ceres Neptune The goddess of The god of the the god of the sky The goddess The god of the sea, the hearth, underworld The goddess of and of thunder of women “The Earth-shaker” household, the harvest and marriage and state ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤΗ Hekate The goddess Aphrodite First-generation Second- generation of magic Venus ΡΕΑ Titans ΚΡΟΝΟΣ Titans The goddess of MagnaRhea Mater Astraeus love and beauty Mnemosyne Kronos Saturn Deucalion Pallas & Perses Pyrrha Kronos cut off the genitals Crius of his father Uranus and threw them into the sea, and Asteria Aphrodite arose from them. -

Attic Dramamailversion.Pptx

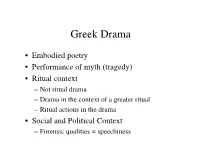

Greek Drama • Embodied poetry • Performance of myth (tragedy) • Ritual context – Not ritual drama – Drama in the context of a greater ritual – Ritual actions in the drama • Social and Political Context – Forensic qualities = speechiness Athenian Dramatic Festivals • The audience: 10-14,000 people, mostly Athenian male citizens, sometimes foreign dignitaries • Poets “applied” for a chorus 6 months before. • Competition during religious festivals for the god Dionysus – City Dionysia (April/March) open to foreign visitors – Lenaia (January) more “closed” to outsiders Performances of: Tragedies (oldest form) (9 plays by 3 tragic poets) Satyr plays (3 plays by the 3 tragic poets) Comedies (1 each by 3 to 5 comic poets) Dithyrambs (10 choruses of men, 10 of boys) Audience saw 4 or 5 plays a day, for three or four days. Tragic mornings, comic afternoons. Other official business was done as well. Evolution of Genres • dithyramb (hymn in honor of Dionysus) • tragedy (diverged from Dionysian themes) – Thespis, 534 BC • satyr play (reinserted Dionysian themes) – included 502-501 BC • Comedy <= from the komos (revelry) ca. 486 BC Origins of Phallic Procession A phallos is a long piece of timber fitted with leather genitalia at the top. The phallos came to be part of the worship of Dionysus by some secret rite. About the phallos itself the following is said. Pegasos took the image of Dionysus from Eleutherai—Eleutherai is a city of Boeotia [a region neighboring Attica, the region of Athens]—and brought it to Attica. The Athenians, however, did not receive the god with reverence, but they did not get away with this resolve unpunished, because, since the god was angry, a disease [priapism?] attacked the men’s genitals and the calamity was incurable.