Faraday's Electrochemical Laws and the Determination of Equivalent Weights'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polymer Exemption Guidance Manual POLYMER EXEMPTION GUIDANCE MANUAL

United States Office of Pollution EPA 744-B-97-001 Environmental Protection Prevention and Toxics June 1997 Agency (7406) Polymer Exemption Guidance Manual POLYMER EXEMPTION GUIDANCE MANUAL 5/22/97 A technical manual to accompany, but not supersede the "Premanufacture Notification Exemptions; Revisions of Exemptions for Polymers; Final Rule" found at 40 CFR Part 723, (60) FR 16316-16336, published Wednesday, March 29, 1995 Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics 401 M St., SW., Washington, DC 20460-0001 Copies of this document are available through the TSCA Assistance Information Service at (202) 554-1404 or by faxing requests to (202) 554-5603. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EQUATIONS............................ ii LIST OF FIGURES............................. ii LIST OF TABLES ............................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ............................ 1 2. HISTORY............................... 2 3. DEFINITIONS............................. 3 4. ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS ...................... 4 4.1. MEETING THE DEFINITION OF A POLYMER AT 40 CFR §723.250(b)... 5 4.2. SUBSTANCES EXCLUDED FROM THE EXEMPTION AT 40 CFR §723.250(d) . 7 4.2.1. EXCLUSIONS FOR CATIONIC AND POTENTIALLY CATIONIC POLYMERS ....................... 8 4.2.1.1. CATIONIC POLYMERS NOT EXCLUDED FROM EXEMPTION 8 4.2.2. EXCLUSIONS FOR ELEMENTAL CRITERIA........... 9 4.2.3. EXCLUSIONS FOR DEGRADABLE OR UNSTABLE POLYMERS .... 9 4.2.4. EXCLUSIONS BY REACTANTS................ 9 4.2.5. EXCLUSIONS FOR WATER-ABSORBING POLYMERS........ 10 4.3. CATEGORIES WHICH ARE NO LONGER EXCLUDED FROM EXEMPTION .... 10 4.4. MEETING EXEMPTION CRITERIA AT 40 CFR §723.250(e) ....... 10 4.4.1. THE (e)(1) EXEMPTION CRITERIA............. 10 4.4.1.1. LOW-CONCERN FUNCTIONAL GROUPS AND THE (e)(1) EXEMPTION................. -

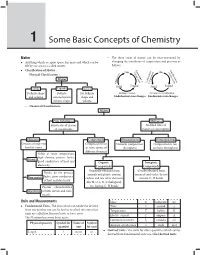

1 Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry

Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry 1 1 Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry Matter – The three states of matter can be inter-converted by Anything which occupies space, has mass and which can be changing the conditions of temperature and pressure as felt by our senses is called matter. follows : Ev Liq Classification of Matter : Co GasGVa ap as uefacti n po orat tion ndensa – tion Physical Classification : io riza at io on n o tion tion Matter lim ndensa or r Deposi Co Sub or Solid Liquid Solid Liquid Solids Liquids Gases Definite shape Definite No definite Melting or Fusion Freezing or Crystallization and volume volume but no shape and Endothermic state changes Exothermic state changes definite shape volume – Chemical Classification : Matter Pure Substances Mixtures Fixed ratio of masses No fixed ratio of of constituents masses of constituents Elements Compounds Homogeneous Heterogeneous Consists of only one Composed of two Uniform composition Composition is not kind of atoms or more atoms of throughout uniform throughout different elements Solids at room temperature, high density, possess lustre, Metals good conductors of heat and Organic Inorganic electricity Compounds Compounds Originally obtained from Usually obtained from Brittle, do not possess animals and plants, contain minerals and rocks, do not lustre, poor conductors Non-metals carbon and few other elements contain C–H bonds of heat and electricity like H, O, S, N, X (halogens), Possess characteristics etc. having C–H bonds Metalloids of both metals and non- metals Units and Measurements Mass m kilogram kg Fundamental Units : The units which can neither be derived Time t second s from one another nor can be further resolved into any other Temperature T kelvin K units are called fundamental units or basic units. -

Basic Concepts and Laws of Chemistry. Guidelines and Objectives for Self-Study Courses for Students in All Specialties / O.Y

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE STATE HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION «NATIONAL MINING UNIVERSITY» O.Y. Svietkina, O.B Netyaga, G.V Tarasova BASIC CONCEPTS AND LAWS OF CHEMISTRY. Guidelines and objectives for self-study courses for students in all specialties Dnipro 2016 THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE STATE HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION «NATIONAL MINING UNIVERSITY» FACULTY OF GEOLOGICAL PROSPECTING Departament of Chemestry O. Y. Svietkina, O.B Netyaga, G.V Tarasova BASIC CONCEPTS AND LAWS OF CHEMISTRY. Guidelines and objectives for self-study courses for students in all specialties Dnipro NMU 2016 Svietkina O. Y. Basic concepts and laws of chemistry. Guidelines and objectives for self-study courses for students in all specialties / O.Y. Svietkina, O.B. Netyaga, G.V. Tarasova; Ministry of eduk. and sien of Ukrain, Nation. min. univer. – D . : NMU, 2016. – 20 p. Автори: О.Ю. Свєткіна, проф., д-р техн. наук (передмова, розділ 2); О.Б. Нетяга, старш. викл. (розділ 1); Г.В. Тарасова, асист. (розділ 2). Затверджено методичною комісією з галузі знань 10. Природничі науки за поданням кафедри хімії (протокол № 3 від 08.11.2016). The theoretical themes of "Basic concepts and laws of chemistry", are examples of solving common tasks, in order to consolidate the material there are presented self-study tasks for solving. Розглянуто теоретичні положення теми «Основні поняття й закони хімії», наведено приклади розв’язку типових задач з метою закріплення матеріалу, подано задачі для самостійного розв’язування. Відповідальна за випуск завідувач кафедри хімії, д-р техн. наук, проф. О.Ю. Свєткіна. Introduction Chemistry studies such form of substance motion which assumes qualitative change of matters i.e. -

(I) Determination of the Equivalent Weight and Pka of an Organic Acid

Experiment 4 (i) Determination of the Equivalent Weight and pKa of an Organic Acid Discussion This experiment is an example of a common research procedure. Chemists often use two or more analytical techniques to study the same system. These experiments can give complementary qualitative and quantitative information concerning an unknown substance. I. Titration of Acids and Bases in Aqueous Solutions The almost instantaneous reaction between acids and bases in aqueous solution produce changes in pH which one can monitor. Two techniques are useful for detecting the equivalence point: (1) colorimetry, using an acid-base color indicator - a dye which undergoes a sharp change in color in a region of pH covering the equivalence point and (2) potentiometry, using a potentiometer (pH meter) to record the sharp change at the equivalence point in the potential difference between an electrode (usually a glass electrode) and the solution whose pH is undergoing change as a result of the addition of acid or base. For example, in the case of the titration of a weak monoprotic acid HA using sodium hydroxide solution we may write: + - NaOH + HA → Na + A + H2O (4.1) Applying the law of mass action to the ionization equilibrium for the weak acid in water: + - HA + H2O H3O + A (4.2) we may write (in dilute solutions [H2O] is essentially constant) [H O+ ][A − ] 3 = K (4.3) [HA] a where Ka is the acid ionization constant (constant at any given temperature). This expression is valid for + - all aqueous solutions containing hydronium ions (H3O ), A ions, and the un-ionized molecules HA. -

PHARMACY CALCULATIONS •Explain Importance of Calculations in Determining Days Supply •Describe Consequences of Calculation Errors

7/7/2016 THE OBJECTIVES INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING: •Discuss importance of calculations in a pharmacy practice. •Outline steps to avoid calculation errors 2016 ANNUAL MEETING •Explain importance of reading the prescription carefully then performing calculations PHARMACY CALCULATIONS •Explain importance of calculations in determining days supply •Describe consequences of calculation errors. •Perform calculations during the presentation 2016 ANNUAL MEETING 4 ADDITIONAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES •Understand how the concentration of electrolyte 2016 ANNUAL MEETING solutions are expressed and calculations of m.Eq. •Understand the importance of iso-tonicity in SUNIL S. JAMBHEKAR, B. PHARM.; M.S., PH.D ophthalmic solutions. PROFESSOR, PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES LECOM BRADENTON, SCHOOL OF PHARMACY •Perform calculations, using a prescription, to BRADENTON, FL34202 determine the quantity of a liquid product required [email protected] to fill the prescription accurately. 2016 ANNUAL MEETING 5 ADDITIONAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES •Perform calculations, using a prescription, to 2016 ANNUAL MEETING determine the # of day supply for a specific DISCLOSURE product. I DO NOT HAVE A VESTED INTEREST IN OR AFFILIATION •Perform calculations to determine m.Eq WITH ANY CORPORATE ORGANIZATION OFFERING FINANCIAL SUPPORT OR GRANT MONIES FOR THIS CONTINUING strength of an electrolyte solution. EDUCATION ACTIVITY, OR ANY AFFILIATION WITH AN ORGANIZATION WHOSE PHILOSOPHY COULD POTENTIALLY •Perform calculations to prepare an isotonic BIAS MY PRESENTATION ophthalmic solution. 2016 ANNUAL MEETING 6 1 7/7/2016 IMPORTANCE OF CALCULATIONS IN THE PHARMACY PRACTICE: •It is consistent with the practice and philosophy of pharmaceutical care. •Insurance companies will reimburse you or •Patient safety is of utmost importance. your employer only for the quantity written on the prescription and not for the quantity •Your pharmacy is the last check point for the dispensed. -

WO 2019/055177 Al 21 March 2019 (21.03.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/055177 Al 21 March 2019 (21.03.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Declarations under Rule 4.17: C08G 65/02 (2006.01) C08G 18/32 (2006.01) — as to applicant's entitlement to apply for and be granted a C08G 65/26 (2006.01) patent (Rule 4.17(H)) (21) International Application Number: — as to the applicant's entitlement to claim the priority of the PCT/US20 18/047252 earlier application (Rule 4.17(Hi)) (22) International Filing Date: Published: 2 1 August 2018 (21.08.2018) — with international search report (Art. 21(3)) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Language: English (30) Priority Data: 62/559,109 15 September 2017 (15.09.2017) US (71) Applicant: DOW GLOBAL TECHNOLOGIES LLC [US/US]; 2040 Dow Center, Midland, Michigan 48674 (US). (72) Inventors: MASY, Jean-Paul; Herbert H . Dowweg 5, 4542 NM Hoek, Postbus 48, 4530AA Terneuzen (NL). BABB, David A.; 230 1N . Brazosport Boulevard, Freeport, Texas 77541 (US). (74) Agent: Gary C Cohn PLLC; 325 7th Avenue, #203, San Diego, California 92101 (US). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available) : AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

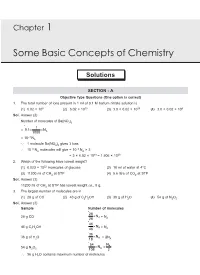

Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry

Chapter 1 Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry Solutions SECTION - A Objective Type Questions (One option is correct) 1. The total number of ions present in 1 ml of 0.1 M barium nitrate solution is (1) 6.02 × 108 (2) 6.02 × 1010 (3) 3.0 × 6.02 × 1019 (4) 3.0 × 6.02 × 108 Sol. Answer (3) Number of molecules of Ba(NO3)2 1 0.1 N = 1000 A –4 = 10 NA ∵ 1 molecule Ba(NO3)2 gives 3 ions –4 –4 10 NA molecules will give = 10 NA × 3 = 3 × 6.02 × 1019 = 1.806 × 1020 2. Which of the following have lowest weight? (1) 6.023 × 1022 molecules of glucose (2) 18 ml of water at 4°C (3) 11200 ml of CH4 at STP (4) 5.6 litre of CO2 at STP Sol. Answer (3) 11200 ml of CH4 at STP has lowest weight i.e., 8 g. 3. The largest number of molecules are in (1) 28 g of CO (2) 46 g of C2H5OH (3) 36 g of H2O (4) 54 g of N2O5 Sol. Answer (3) Sample Number of molecules 28 NA 28 g CO 28 = NA 46 NA 46 g C2H5OH 46 = NA 36 NA 36 g of H2O 18 = 2NA 54 NA NA 54 g N2O5 108 2 36 g H2O contains maximum number of molecules 2 Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry Solution of Assignment 4. The volume of 0.1 M Ca(OH)2 needed for the neutralization of 40 ml of 0.05 M oxalic acid is (1) 10 ml (2) 20 ml (3) 30 ml (4) 40 ml Sol. -

Determination of the Equivalent Weight and the Ka Or Kb for a Weak Acid Or Base INTRODUCTION Chemists Frequently Make Use of the Equivalent Weight (Eq

Determination of the Equivalent Weight and the Ka or Kb for a Weak Acid or Base INTRODUCTION Chemists frequently make use of the equivalent weight (eq. wt.) as the basis for volumetric calculations. The meaning of equivalent weight can change depending upon the type of reaction which serves as the basis for analysis, i.e., neutralization, oxidation-reduction, precipitation, or complex formation. Furthermore, it should be noted that the chemical behavior of a substance must be carefully specified if its equivalent weight is to be unambiguously defined. The equivalent weight of a substance involved in a neutralization (acid/base) reaction is defined as that weight which reacts with or contributes 1 gram formula weight of hydrogen ion in that reaction. This is discussed at some length in your textbook. In this experiment, you will be given a compound which is either a pure weak acid or a pure weak base. You are asked to determine the nature of the substance (i.e. is it an acid or a base?), its equivalent weight, and its dissociation constant. If possible, using the values you obtain and the CRC Handbook, identify your compound. REAGENTS Ethanol, phenolphthalein and methyl red indicators are provided for you. PROCEDURE 1. Obtain your unknown weak acid or base, and dry it as instructed to do so if it is a solid. 2. To determine the nature of your compound: Dissolve a small amount of your unknown in water. If you find your unknown to be rather insoluble in water, try heating the solution. If this also proves unsuccessful, you will need to switch to a 10% ethanol/water mixture. -

Molecular Mass and Gram-Molecule of a Substance

STOICHIOMETRY ATOMIC MASSS The atomic mass of an element is defined as the average relative mass of an atom of the element as compared to the mass of a carbon atom, which is taken as 12. Therefore, the atomic mass of an element shows the number of times an atom of the element is heavier than 1/12th of the mass of a carbon atom (C12). For example, the atomic mass of an oxygen atom is 16 a.m.u (atomic mass unit) and that of a hydrogen atom is 1.008 a.m.u. Atomic mass unit—abbreviated as a.m.u—is defined as the quantity of mass of an atom equal to 1/12 of the mass of a carbon atom. By convention, the atomic mass of a carbon atom is 12 a.m.u. One mole of carbon signifies 6.023 1023 atoms of carbon, and a mass of 12.000 g. Therefore, the mass of a carbon atom can be calculated as follows: 24 12.00/6.023 1023 g or 1 a.m.u. = = = 1.66 10 G Gram-atomic mass of an element is the atomic mass of the element expressed in grams. It is also known as gram atom. For example, 16 g of oxygen is equal to 1 gram-atom of oxygen or 14 g of nitrogen is equal to 1 gram-atom of nitrogen. Gram-atom can be calculated as shown below: Gram atom = Molecular Mass and Gram-Molecule of a Substance Molecular mass of a compound is defined as the average mass per molecule of natural isotopic composition of the compound. -

DOE-HDBK-1015/1-92; DOE Fundamentals Handbook Chemistry Volume 1 of 2

Fundamentals of Chemistry Course No: H05-001 Credit: 5 PDH Gilbert Gedeon, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Department of Energy Fundamentals Handbook CHEMISTRY Module 1 Fundamentals of Chemistry Fundamentals of Chemistry DOE-HDBK-1015/1-93 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ................................................... v REFERENCES .................................................... vi OBJECTIVES ..................................................... vii CHARACTERISTICS OF ATOMS ...................................... 1 Characteristics of Matter ......................................... 1 The Atom Structure ............................................ 2 Chemical Elements ............................................ 3 Molecules ................................................... 7 Avogadro’s Number ............................................ 8 The Mole ................................................... 9 Mole of Molecules............................................. 10 Summary ................................................... 11 THE PERIODIC TABLE ............................................. 12 Periodic Table ................................................ 12 Classes of the Periodic Table ..................................... 16 Group Characteristics ........................................... 18 Atomic Structure of Electrons .................................... -

The Elements.Pdf

A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos National Laboratory's Chemistry Division Presents Periodic Table of the Elements A Resource for Elementary, Middle School, and High School Students Click an element for more information: Group** Period 1 18 IA VIIIA 1A 8A 1 2 13 14 15 16 17 2 1 H IIA IIIA IVA VA VIAVIIA He 1.008 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 4.003 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 Li Be B C N O F Ne 6.941 9.012 10.81 12.01 14.01 16.00 19.00 20.18 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 3 Na Mg IIIB IVB VB VIB VIIB ------- VIII IB IIB Al Si P S Cl Ar 22.99 24.31 3B 4B 5B 6B 7B ------- 1B 2B 26.98 28.09 30.97 32.07 35.45 39.95 ------- 8 ------- 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 4 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr 39.10 40.08 44.96 47.88 50.94 52.00 54.94 55.85 58.47 58.69 63.55 65.39 69.72 72.59 74.92 78.96 79.90 83.80 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 5 Rb Sr Y Zr NbMo Tc Ru Rh PdAgCd In Sn Sb Te I Xe 85.47 87.62 88.91 91.22 92.91 95.94 (98) 101.1 102.9 106.4 107.9 112.4 114.8 118.7 121.8 127.6 126.9 131.3 55 56 57 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 6 Cs Ba La* Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt AuHg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn 132.9 137.3 138.9 178.5 180.9 183.9 186.2 190.2 190.2 195.1 197.0 200.5 204.4 207.2 209.0 (210) (210) (222) 87 88 89 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 114 116 118 7 Fr Ra Ac~RfDb Sg Bh Hs Mt --- --- --- --- --- --- (223) (226) (227) (257) (260) (263) (262) (265) (266) () () () () () () http://pearl1.lanl.gov/periodic/ (1 of 3) [5/17/2001 4:06:20 PM] A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 Lanthanide Series* Ce Pr NdPmSm Eu Gd TbDyHo Er TmYbLu 140.1 140.9 144.2 (147) 150.4 152.0 157.3 158.9 162.5 164.9 167.3 168.9 173.0 175.0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 Actinide Series~ Th Pa U Np Pu AmCmBk Cf Es FmMdNo Lr 232.0 (231) (238) (237) (242) (243) (247) (247) (249) (254) (253) (256) (254) (257) ** Groups are noted by 3 notation conventions. -

Moles and Molarity 6 Equivalent Weights and Normality 7 Dilution Calculations 8 Standard Solutions 12

This is the table of contents and a sample chapter from WSO Water Treatment, Grade 2, get your full copy from AWWA. awwa.org/wso © 2016 American Water Works Association Contents Chapter 1 Basic Microbiology and Chemistry 1 Chemical Formulas and Equations 1 Moles and Molarity 6 Equivalent Weights and Normality 7 Dilution Calculations 8 Standard Solutions 12 Chapter 2 Operator Math 15 Volume Measurements 15 Conversions 22 Average Daily Flow 30 Surface Overflow Rate 33 Weir Overflow Rate 36 Filter Loading Rate 38 Filter Backwash Rate 41 Mudball Calculation 43 Detention Time 44 Pressure 47 Flow Rate Problems 52 Chemical Dosage Problems 55 Chapter 3 USEPA Water Regulations 71 Types of Water Systems 71 Disinfection By- product and Microbial Regulations 72 Chapter 4 Coagulation and Flocculation Process Operation 89 Operation of the Processes 89 Dosage Control 93 Safety Precautions 93 Record Keeping 94 Chapter 5 Sedimentation and Clarifiers 97 Process Description 97 Sedimentation Facilities 98 Other Clarification Processes 104 Regulations 107 Operation of the Process 107 iii 000200010272023365_ch00_FM_pi-vi.indd 3 5/2/16 9:51 AM iv WSO Water Treatment Grade 2 Chapter 6 Filtration 115 Equipment Associated With Gravity Filters 115 Operation of Gravity Filters 123 Pressure Filtration 135 Regulations 138 Safety Precautions 138 Record Keeping 139 Chapter 7 Chlorine Disinfection 143 Gas Chlorination Facilities 143 Hypochlorination Facilities 155 Operation of the Chlorination Process 157 Chlorination Operating Problems 162 Safety Precautions 165 Record