Quantitative Electrochemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of Copper Electroplating And

CHARACTERIZATION OF COPPER ELECTROPLATING AND ELECTROPOLISHING PROCESSES FOR SEMICONDUCTOR INTERCONNECT METALLIZATION by JULIE MARIE MENDEZ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Uziel Landau Department of Chemical Engineering CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________ candidate for the ______________________degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Number List of Tables 3 List of Figures 4 Acknowledgements 9 List of Symbols 10 Abstract 13 1. Introduction 15 1.1 Semiconductor Interconnect Metallization – Process Description 15 1.2 Mechanistic Aspects of Bottom-up Fill 20 1.3 Electropolishing 22 1.4 Topics Addressed in the Dissertation 24 2. Experimental Studies of Copper Electropolishing 26 2.1 Experimental Procedure 29 2.2 Polarization Studies 30 2.3 Current Steps 34 2.3.1 Current Stepped to a Level below Limiting Current 34 2.3.2 Current Stepped to the Limiting -

Electrolytic Cells

CHEMISTRY LEVEL 4C (CHM415115) ELECTROLYTIC CELLS THEORY SUMMARY & REVISION QUESTIONS (CRITERION 5) ©JAK DENNY Tasmanian TCE Chemistry Revision Guides by Jak Denny are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. INDEX: PAGES • INTRODUCTORY THEORY 3 • COMPARING ENERGY CONVERSIONS 4 • APPLICATIONS OF ELECTROLYSIS 4 • ELECTROPLATING 5 • COMPARING CELLS 6 • THE ELECTROCHEMICAL SERIES 7 • PREDICTING ELECTROLYSIS PRODUCTS 8-9 • ELECTROLYSIS PREDICTION FLOWCHART 1 0 • ELECTROLYSIS PREDICTION EXAMPLES 11 • ELECTROLYSIS PREDICTION QUESTIONS 12 • INDUSTRIAL ELECTROLYTIC PROCESSES 13 • IMPORTANT ELECTRICAL THEORY 14 • FARADAY’S ELECTROLYSIS LAWS 15 • QUANTITATIVE ELECTROLYSIS 16 • CELLS IN SERIES 17 • ELECTROLYSIS QUESTIONS 18-20 • ELECTROLYSIS TEST QUESTIONS 21-22 • TEST ANSWERS 23 2 ©JAK CHEMISTRY LEVEL 4C (CHM415115) ELECTROLYTIC CELLS (CRITERION 5) INTRODUCTION: In our recent investigation of electrochemical cells, we encountered spontaneous redox reactions that release electrical energy such as takes place in the familiar situations of “batteries”. When a car battery is ‘flat’ and needs to be recharged, a power supply (‘battery charger’) is connected to the flat battery and chemical changes take place and it is subsequently able to operate again as a power supply. The ‘recharging’ process is non-spontaneous and requires an input of energy to occur. When a cell is such that an energy input is required to make a non-spontaneous redox reaction take place, we describe the cell as an ELECTROLYTIC CELL. The redox process occurring in an ELECTROLYTIC CELL is referred to as ELECTROLYSIS. For example, consider the spontaneous redox reaction associated with an electrochemical (fuel) cell; i.e. 2H2(g) + O2(g) → 2H2O(l) + ELECTRICAL ENERGY This chemical reaction RELEASES energy which can be used to power an electric motor, to drive a machine, appliance or car. -

Resume Wonsub Chung

Resume Wonsub Chung Contact Information Wonsub Chung, ph.D. Professor Division of Material Science & Engineering Pusan National University 2, Busandaehak-ro 63beon-gil, Geumjeong-gu Busan, 46241 Korea e-mail:[email protected] Tel: +82-51-510-2386 H.P. : +82-10-8517-0855 Fax : +82-51-514-4457 Personal DOB : 1-23-1957, Male, Married, Born in South Korea Education Ph.D., Materials Science and Engineering. 1985-1989 Kyushu University, Hukuoka, Japan(Advisor: Prof. Ono Yoichi) Thesis: A Basic Study on Gas Reduction of Calcium Ferrite M.S., Materials Science and Engineering, 1983-1985 Pusan National University, Busan, South Korea (Advisor: Prof. Kyusub Song) Thesis: B.S., Materials Science and Engineering, 1978-1983 Pusan National University, Busan, South Korea, Major Career ∎ 1989-1992 Chief Researcher RIST(Research Institute of Industrial Science & Technology) Iron Ore Melting Reduction Research Project Team ∎ 1993-Present : Professor Pusan National University Division of Material Science & Engineering ∎ 1999-2000 Exchange professor Colorado School of Mines, Colorado, USA Research Interests Energy saving and Radiation Heat transfer and dissipation Study on Water Electrolysis Using Radiation and Electrical Energy Study on Reduction of Covalent Bonding Energy of Reaction Using Radiation and Electric Energy A study on the gasification reaction of coal using radiant energy Electrochemical anodic oxidation and deposition Corrosion and prevention of metallic materials (Mg, Al alloys and steels) Surface physics and chemistry Expertise -

Electrochemical Cells

Electrochemical cells = electronic conductor If two different + surrounding electrolytes are used: electrolyte electrode compartment Galvanic cell: electrochemical cell in which electricity is produced as a result of a spontaneous reaction (e.g., batteries, fuel cells, electric fish!) Electrolytic cell: electrochemical cell in which a non-spontaneous reaction is driven by an external source of current Nils Walter: Chem 260 Reactions at electrodes: Half-reactions Redox reactions: Reactions in which electrons are transferred from one species to another +II -II 00+IV -II → E.g., CuS(s) + O2(g) Cu(s) + SO2(g) reduced oxidized Any redox reactions can be expressed as the difference between two reduction half-reactions in which e- are taken up Reduction of Cu2+: Cu2+(aq) + 2e- → Cu(s) Reduction of Zn2+: Zn2+(aq) + 2e- → Zn(s) Difference: Cu2+(aq) + Zn(s) → Cu(s) + Zn2+(aq) - + - → 2+ More complex: MnO4 (aq) + 8H + 5e Mn (aq) + 4H2O(l) Half-reactions are only a formal way of writing a redox reaction Nils Walter: Chem 260 Carrying the concept further Reduction of Cu2+: Cu2+(aq) + 2e- → Cu(s) In general: redox couple Ox/Red, half-reaction Ox + νe- → Red Any reaction can be expressed in redox half-reactions: + - → 2 H (aq) + 2e H2(g, pf) + - → 2 H (aq) + 2e H2(g, pi) → Expansion of gas: H2(g, pi) H2(g, pf) AgCl(s) + e- → Ag(s) + Cl-(aq) Ag+(aq) + e- → Ag(s) Dissolution of a sparingly soluble salt: AgCl(s) → Ag+(aq) + Cl-(aq) − 1 1 Reaction quotients: Q = a − ≈ [Cl ] Q = ≈ Cl + a + [Ag ] Ag Nils Walter: Chem 260 Reactions at electrodes Galvanic cell: -

3 PRACTICAL APPLICATION BATTERIES and ELECTROLYSIS Dr

ELECTROCHEMISTRY – 3 PRACTICAL APPLICATION BATTERIES AND ELECTROLYSIS Dr. Sapna Gupta ELECTROCHEMICAL CELLS An electrochemical cell is a system consisting of electrodes that dip into an electrolyte and in which a chemical reaction either uses or generates an electric current. A voltaic or galvanic cell is an electrochemical cell in which a spontaneous reaction generates an electric current. An electrolytic cell is an electrochemical cell in which an electric current drives an otherwise nonspontaneous reaction. Dr. Sapna Gupta/Electrochemistry - Applications 2 GALVANIC CELLS • Galvanic cell - the experimental apparatus for generating electricity through the use of a spontaneous reaction • Electrodes • Anode (oxidation) • Cathode (reduction) • Half-cell - combination of container, electrode and solution • Salt bridge - conducting medium through which the cations and anions can move from one half-cell to the other. • Ion migration • Cations – migrate toward the cathode • Anions – migrate toward the anode • Cell potential (Ecell) – difference in electrical potential between the anode and cathode • Concentration dependent • Temperature dependent • Determined by nature of reactants Dr. Sapna Gupta/Electrochemistry - Applications 3 BATTERIES • A battery is a galvanic cell, or a series of cells connected that can be used to deliver a self-contained source of direct electric current. • Dry Cells and Alkaline Batteries • no fluid components • Zn container in contact with MnO2 and an electrolyte Dr. Sapna Gupta/Electrochemistry - Applications 4 ALKALINE CELL • Common watch batteries − − Anode: Zn(s) + 2OH (aq) Zn(OH)2(s) + 2e − − Cathode: 2MnO2(s) + H2O(l) + 2e Mn2O3(s) + 2OH (aq) This cell performs better under current drain and in cold weather. It isn’t truly “dry” but rather uses an aqueous paste. -

Electroless Copper Plating a Review: Part I

Electroless Copper Plating A Review: Part I By Cheryl A. Deckert Electroless, or autocatalytic, metal plating is a non- necessary components of an electro- electrolytic method of deposition from solution. The less plating solution are the metal salt minimum necessary components of an electroless and a reducing agent. The source of plating solution are a metal salt and an appropriate copper is a simple cupric salt, such as reducing agent. An additional requirement is that the copper sulfate, chloride or nitrate. solution, although thermodynamically unstable, is Various common reducing agents stable in practice until a suitable catalyzed surface is have been suggested7 for use in elec- introduced. Plating is then initiated upon the catalyzed troless copper baths, namely formal- surface, and the plating reaction is sustained by the dehyde, dimethylamine borane, boro- catalytic nature of the plated metal surface itself. This hydride, hypophosphite,8 hydrazine, definition of electroless plating eliminates both those sugars (sucrose, glucose, etc.), and solutions that spontaneously plate on all surfaces dithionite. In practice, however, vir- (“homogeneous chemical reduction”), such as silver tually all commercial electroless cop- mirroring solutions; also “immersion” plating solu- per solutions have utilized formalde- tions, which deposit by displacement a very thin film of hyde as reducing agent. This is a a relatively noble metal onto the surface of a sacrificial, result of the combination of cost, less noble metal. effectiveness, and ease -

Polymer Exemption Guidance Manual POLYMER EXEMPTION GUIDANCE MANUAL

United States Office of Pollution EPA 744-B-97-001 Environmental Protection Prevention and Toxics June 1997 Agency (7406) Polymer Exemption Guidance Manual POLYMER EXEMPTION GUIDANCE MANUAL 5/22/97 A technical manual to accompany, but not supersede the "Premanufacture Notification Exemptions; Revisions of Exemptions for Polymers; Final Rule" found at 40 CFR Part 723, (60) FR 16316-16336, published Wednesday, March 29, 1995 Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics 401 M St., SW., Washington, DC 20460-0001 Copies of this document are available through the TSCA Assistance Information Service at (202) 554-1404 or by faxing requests to (202) 554-5603. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EQUATIONS............................ ii LIST OF FIGURES............................. ii LIST OF TABLES ............................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ............................ 1 2. HISTORY............................... 2 3. DEFINITIONS............................. 3 4. ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS ...................... 4 4.1. MEETING THE DEFINITION OF A POLYMER AT 40 CFR §723.250(b)... 5 4.2. SUBSTANCES EXCLUDED FROM THE EXEMPTION AT 40 CFR §723.250(d) . 7 4.2.1. EXCLUSIONS FOR CATIONIC AND POTENTIALLY CATIONIC POLYMERS ....................... 8 4.2.1.1. CATIONIC POLYMERS NOT EXCLUDED FROM EXEMPTION 8 4.2.2. EXCLUSIONS FOR ELEMENTAL CRITERIA........... 9 4.2.3. EXCLUSIONS FOR DEGRADABLE OR UNSTABLE POLYMERS .... 9 4.2.4. EXCLUSIONS BY REACTANTS................ 9 4.2.5. EXCLUSIONS FOR WATER-ABSORBING POLYMERS........ 10 4.3. CATEGORIES WHICH ARE NO LONGER EXCLUDED FROM EXEMPTION .... 10 4.4. MEETING EXEMPTION CRITERIA AT 40 CFR §723.250(e) ....... 10 4.4.1. THE (e)(1) EXEMPTION CRITERIA............. 10 4.4.1.1. LOW-CONCERN FUNCTIONAL GROUPS AND THE (e)(1) EXEMPTION................. -

Physical Chemistry LD

Physical Chemistry LD Electrochemistry Chemistry Electrolysis Leaflets C4.4.5.2 Determining the Faraday constant Aims of the experiment To perform an electrolysis. To understand redox reactions in practice. To work with a Hoffman electrolysis apparatus. To understand Faraday’s laws. To understand the ideal gas equation. The second law is somewhat more complex. It states that the Principles mass m of an element that is precipitated by a specific When a voltage is applied to a salt or acid solution, material amount of charge Q is proportional to the atomic mass, and is migration occurs at the electrodes. Thus, a chemical reaction inversely proportional to its valence. Stated more simply, the is forced to occur through the flow of electric current. This same amount of charge Q from different electrolytes always process is called electrolysis. precipitates the same equivalent mass Me. The equivalent mass Me is equal to the molecular mass of an element divid- Michael Faraday had already made these observations in the ed by its valence z. 1830s. He coined the terms electrolyte, electrode, anode and cathode, and formulated Faraday's laws in 1834. These count M M = as some of the foundational laws of electrochemistry and e z describe the relationships between material conversions In order to precipitate this equivalent mass, 96,500 Cou- during electrochemical reactions and electrical charge. The lombs/mole are always needed. This number is the Faraday first of Faraday’s laws states that the amount of moles n, that constant, which is a natural constant based on this invariabil- are precipitated at an electrode is proportional to the charge ity. -

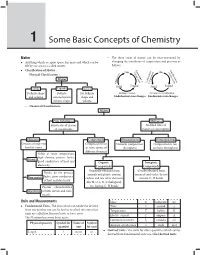

1 Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry

Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry 1 1 Some Basic Concepts of Chemistry Matter – The three states of matter can be inter-converted by Anything which occupies space, has mass and which can be changing the conditions of temperature and pressure as felt by our senses is called matter. follows : Ev Liq Classification of Matter : Co GasGVa ap as uefacti n po orat tion ndensa – tion Physical Classification : io riza at io on n o tion tion Matter lim ndensa or r Deposi Co Sub or Solid Liquid Solid Liquid Solids Liquids Gases Definite shape Definite No definite Melting or Fusion Freezing or Crystallization and volume volume but no shape and Endothermic state changes Exothermic state changes definite shape volume – Chemical Classification : Matter Pure Substances Mixtures Fixed ratio of masses No fixed ratio of of constituents masses of constituents Elements Compounds Homogeneous Heterogeneous Consists of only one Composed of two Uniform composition Composition is not kind of atoms or more atoms of throughout uniform throughout different elements Solids at room temperature, high density, possess lustre, Metals good conductors of heat and Organic Inorganic electricity Compounds Compounds Originally obtained from Usually obtained from Brittle, do not possess animals and plants, contain minerals and rocks, do not lustre, poor conductors Non-metals carbon and few other elements contain C–H bonds of heat and electricity like H, O, S, N, X (halogens), Possess characteristics etc. having C–H bonds Metalloids of both metals and non- metals Units and Measurements Mass m kilogram kg Fundamental Units : The units which can neither be derived Time t second s from one another nor can be further resolved into any other Temperature T kelvin K units are called fundamental units or basic units. -

Basic Concepts and Laws of Chemistry. Guidelines and Objectives for Self-Study Courses for Students in All Specialties / O.Y

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE STATE HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION «NATIONAL MINING UNIVERSITY» O.Y. Svietkina, O.B Netyaga, G.V Tarasova BASIC CONCEPTS AND LAWS OF CHEMISTRY. Guidelines and objectives for self-study courses for students in all specialties Dnipro 2016 THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE STATE HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION «NATIONAL MINING UNIVERSITY» FACULTY OF GEOLOGICAL PROSPECTING Departament of Chemestry O. Y. Svietkina, O.B Netyaga, G.V Tarasova BASIC CONCEPTS AND LAWS OF CHEMISTRY. Guidelines and objectives for self-study courses for students in all specialties Dnipro NMU 2016 Svietkina O. Y. Basic concepts and laws of chemistry. Guidelines and objectives for self-study courses for students in all specialties / O.Y. Svietkina, O.B. Netyaga, G.V. Tarasova; Ministry of eduk. and sien of Ukrain, Nation. min. univer. – D . : NMU, 2016. – 20 p. Автори: О.Ю. Свєткіна, проф., д-р техн. наук (передмова, розділ 2); О.Б. Нетяга, старш. викл. (розділ 1); Г.В. Тарасова, асист. (розділ 2). Затверджено методичною комісією з галузі знань 10. Природничі науки за поданням кафедри хімії (протокол № 3 від 08.11.2016). The theoretical themes of "Basic concepts and laws of chemistry", are examples of solving common tasks, in order to consolidate the material there are presented self-study tasks for solving. Розглянуто теоретичні положення теми «Основні поняття й закони хімії», наведено приклади розв’язку типових задач з метою закріплення матеріалу, подано задачі для самостійного розв’язування. Відповідальна за випуск завідувач кафедри хімії, д-р техн. наук, проф. О.Ю. Свєткіна. Introduction Chemistry studies such form of substance motion which assumes qualitative change of matters i.e. -

(I) Determination of the Equivalent Weight and Pka of an Organic Acid

Experiment 4 (i) Determination of the Equivalent Weight and pKa of an Organic Acid Discussion This experiment is an example of a common research procedure. Chemists often use two or more analytical techniques to study the same system. These experiments can give complementary qualitative and quantitative information concerning an unknown substance. I. Titration of Acids and Bases in Aqueous Solutions The almost instantaneous reaction between acids and bases in aqueous solution produce changes in pH which one can monitor. Two techniques are useful for detecting the equivalence point: (1) colorimetry, using an acid-base color indicator - a dye which undergoes a sharp change in color in a region of pH covering the equivalence point and (2) potentiometry, using a potentiometer (pH meter) to record the sharp change at the equivalence point in the potential difference between an electrode (usually a glass electrode) and the solution whose pH is undergoing change as a result of the addition of acid or base. For example, in the case of the titration of a weak monoprotic acid HA using sodium hydroxide solution we may write: + - NaOH + HA → Na + A + H2O (4.1) Applying the law of mass action to the ionization equilibrium for the weak acid in water: + - HA + H2O H3O + A (4.2) we may write (in dilute solutions [H2O] is essentially constant) [H O+ ][A − ] 3 = K (4.3) [HA] a where Ka is the acid ionization constant (constant at any given temperature). This expression is valid for + - all aqueous solutions containing hydronium ions (H3O ), A ions, and the un-ionized molecules HA. -

The Laby Experiment

Anna Binnie The Laby Experiment Abstract After J.J. Thomson demonstrated that the atom was not an indivisible entity but contained negatively charged corpuscles, the search for the determination of magnitude of this fundamental unit of electric charge commenced. This paper will briefly discuss the different attempts to measure this quantity of unit charge e. It will outline the progress of these attempts and will focus on the little known work of Australian, Thomas Laby, who attempted to reconcile the value of e determined from two very different approaches. This was probably the last attempt to measure e and was made at a time that most of the scientific world was busy with other issues. The measurement of the unit electric charge e, by timing the fall of charged oil drops is an experiment that has been performed by generations of undergraduate physics students. The experiment is often termed the Millikan oil drop experiment after R.A. Millikan (1868-1953) who conceived and performed it during the period 1907-1917. This experiment was repeated in 1939-40 by V.D. Hopper (1913b), lecturer in Natural Philosophy at Melbourne University and T.H. Laby (1880-1946) who was Professor. As far as we know this was the last time that the experiment was performed “seriously”, i.e. performed carefully by professional physicists and fully reported in major journals. The question arises who was Laby and why did he conduct this experiment such along time after Millikan has completed his work? Thomas Laby was born in 1880 at Creswick Victoria. In 1883 the family moved to New South Wales where young Thomas was educated.