Frank Walker Memorial Lecture 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

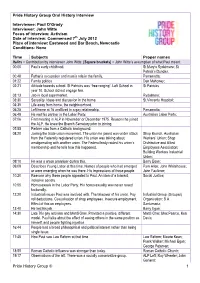

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

Port-Oriented Coal Transport Infrastructure: an Analysis of Locational Decision-Making

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1984 Port-oriented coal transport infrastructure: an analysis of locational decision-making Sophia Apolonia Everett University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Everett, Sophia Apolonia, Port-oriented coal transport infrastructure: an analysis of locational decision- making, Master of Arts thesis, Department of Geography, University of Wollongong, 1984. -

Engineer and Water Commissioner, Was Born on 17 June 1899 At

E EAST, SIR LEWIS RONALD the other commissioner’s health broke down, (RON) (1899–1994), engineer and water leaving East as the sole member. In October commissioner, was born on 17 June 1899 at he was appointed chairman, a position he Auburn, Melbourne, second of three children held until his retirement on 31 January 1965 of Lewis Findlay East, civil servant and later (believed at the time to be the longest tenure as secretary of the Commonwealth Marine head of a government department or authority Branch, and his wife Annie Eleanor, née in Australia). An outstanding engineer, Burchett, both Victorian born. Ronald was inspiring leader, efficient administrator, educated at Ringwood and Tooronga Road and astute political operator, he dominated State schools before winning a scholarship successive water ministers with his forceful to Scotch College, Hawthorn, which he personality and unmatched knowledge of attended from 1913 to 1916, in his final year Victoria’s water issues. He also served as a River winning a government senior scholarship to Murray commissioner (1936–65), in which the University of Melbourne (BEng, 1922; role he exerted great influence on water policy MEng, 1924). throughout south-east Australia. Among many Interrupting his university studies after one examples, he argued successfully for a large year, East enlisted in the Australian Imperial increase in the capacity of the Hume Reservoir. Force on 17 January 1918 for service in World Possibly the most famous photograph used to War I. He arrived in England in May as a 2nd illustrate Australia’s water problems shows East class air mechanic and began flying training in in 1923 literally standing astride the Murray October. -

Inaugural Speeches Inaugural Speeches Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday 6 May 2015

Inaugural Speeches Inaugural Speeches Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday 6 May 2015. Page: 241 The SPEAKER: On behalf of the member for Granville, I acknowledge the presence in the gallery of the Federal member for Werriwa, Mr Laurie Ferguson, MHR, as well as family, friends and supporters of the new member. Ms JULIA FINN (Granville) [5.54 p.m.] (Inaugural Speech): I am honoured to stand here as the member for Granville and as a representative of the Australian Labor Party. Labor has a long and proud tradition of local representation in Granville, and I am pleased and honoured to recommence that representation after the recent election. The possibilities open to parliamentarians to improve the lives of others by creating opportunities and providing protections for the vulnerable has been a great motivation. The electorate of Granville was created in 1894. It elected the Labor candidate, George Smailes, who was born in Durham and who started work at the age of 10 in coalmines at Newcastle. He studied at night to educate himself and eventually became a minister. Some time after migrating to New South Wales he was appointed Pastor of the Primitive Methodist Church at Parramatta. The next Labor representative, elected in 1913, was former Premier J. T. Lang, who represented the electorate of Granville until 1920. He was instrumental in the introduction of valuable social legislation to implement the 44-hour working week; advances in workers compensation, including compulsory insurance; establishment of the Industrial Relations Commission; and the elimination of fees for secondary education. It was a privilege to know Jack Ferguson, the former Deputy Premier and member for Merrylands, which now falls within the Granville electorate, whom I came to know after his retirement. -

Basket Weavers and True Believers the Middle Class Left and the ALP Leichhardt Municipality C

Basket Weavers and True Believers The Middle Class Left and the ALP Leichhardt Municipality c. 1970-1990 by Tony Harris A thesis presented to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Library Copy Sydney, Australia, 2002 © Tony Harris, 2002 Certificate of Originality. ii iii Acknowledgements This thesis is in large part based on oral history interviews and I wish to express my gratitude for the generous time given by informants, in participating in recorded interviews or in providing written responses. I also wish to thank the Australian Labor Party, New South Wales Branch for granting access to the Party’s archival sources at the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, as well as for communicating with local branch and electorate council secretaries on my behalf. Jack Bolton, David West, Robert Grieve and the late Greg Johnston generously made local branch records available and Sue Tracey of the NSW ALP Labor History group provided valuable advice. I would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the Federal Department of Administration and Finance in giving permission to access the records of the Glebe Project Office in the National Archives. Further thanks are due to a wide range of people who were of assistance. The staff of the State Library of NSW, including Rosemary Bloch, Jim Andrighetti and Arthur Easton. The archivists and librarians from the NSW Housing Department Library, Leichhardt Municipal Library and National Archives of Australia, Chester Hill. George Georgarkis and Dianne Walker at Leichhardt Council. -

Gough Whitlam and the ‘Grounds’ for a University of Western Sydney

THE WHITLAM LEGACY A SERIES OF OCCASIONAL PAPERS PUBLISHED BY THE WHITLAM INSTITUTE VOL 1 | OCTOBER 2011 GOUGH WHITLAM AND THE ‘Grounds’ FOR A UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY ‘ A riveder le stelle’ DR MARK HUTCHINSON Editing: The Whitlam Institute ISBN: 978-1-74108-225-8 Copyright: The Whitlam Institute within the University of Western Sydney, 2011 Authored by Dr Mark Hutchinson Mark Hutchinson took a PhD in History at the University of NSW (1989), with a thesis on the development of 19th century Australian historiography. He has been particularly interested in Australian cultural and intellectual history. From 1990-91, he was senior researcher (with Professor Bruce Mansfield) on the Macquarie University 25 Year History Project, which resulted in the book Liberality of Opportunity: A History of Macquarie University 1964-1989 (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1992). At the completion of that project, he took up the position as founding Director of the Centre for the Study of Australian Christianity at Robert Menzies College (1991-1999), a research centre which produced numerous books, articles and working papers, and which attracted significant interest internationally. From 1998-2002, in addition, Mark was Assistant Director of the Currents in World Christianity Project at Cambridge University. From 2000-2010, he was Dean, Graduate Studies (later Dean of Academic Advancement), and Reader in History and Society, at Alphacrucis College, Sydney. Mark is currently University Historian at the University of Western Sydney in preparation for the celebration of the University’s 25th Anniversary in 2014, a position which he feels may best be viewed as helping one of Australia’s great universities reflect upon its own nature, mission and heritage. -

Factions and Fractions: a Case Study of Power Politics in the Australian Labor Party

Australian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 427– 448 Factions and Fractions: A Case Study of Power Politics in the Australian Labor Party ANDREW LEIGH Of ce of the Shadow Minister for Trade, Canberra Over the past three decades, factions have cemented their hold over the Australian Labor Party. This has largely been due to the entrenchment of the proportional representation of factions. One of the effects of the institutionalisa- tion of factions has been the development of factional sub-groupings (‘frac- tions’). This article analyses the phenomenon by looking at a case study of a single ALP faction—the Left in New South Wales. Since 1971, two major fractions have developed in the NSW Left, based on ideological disagreements, personality con icts, generational differences and arguments over the role of the union movement in the ALP. This development parallels the intra-factional splits that have occurred in many other sections of the Labor Party. Yet the factional system in the 1980s and 1990s operated relatively effectively as a means of managing power. The question now is whether it can survive the challenge of new issues that cross-cut traditional ideological lines. Introduction Factionalism in the Australian Labor Party (ALP) is a phenomenon much remarked upon, but little analysed. Like the role of the Ma a in Italian politics, few outside the system seem to understand the power networks, whilst few inside are prepared to share their thoughts with the outside world. Yet without understanding factions, it is impossible to properly comprehend the Labor Party. Every organisation, and certainly every political party, contains organised power groupings. -

Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard No. 9, 2002 WEDNESDAY, 18 SEPTEMBER 2002 FORTIETH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—THIRD PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard SITTING DAYS—2002 Month Date February 12, 13, 14 March 11, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21 May 14, 15, 16 June 17, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26, 27 August 19, 20, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29 September 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26 October 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24 November 11, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21 December 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM SENATE CONTENTS WEDNESDAY, 18 SEPTEMBER Temporary Chairmen of Committees.................................................................. 4335 Ministerial Statements— Foreign Affairs: Iraq...................................................................................... 4335 Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Bill (No. 1) 2002— In Committee................................................................................................. 4336 Adoption of Report....................................................................................... -

A Chip Off the Old Block | Newmatilda.Com 3/09/09 5:57 PM

A Chip Off The Old Block | newmatilda.com 3/09/09 5:57 PM Home Recent Articles Archive About Us FAQ Contribute Contact Search Sign in | Register CLIMATE POLICY 2 Sep 2009 A Chip Off The Old Block Email Font size By Declan Kuch Share Print Dynastic ALP politician Martin Ferguson Declan Kuch is a cyclist who researches carbon is one piece of the puzzle of what’s markets at the University of New South Wales. He is also a policy adviser to the Australian Youth stalling energy and climate policy in Climate Coalition. Australia, writes Declan Kuch Read Declan Kuch's full bio Kevin Rudd might have been elected on a wave of resentment about Howard's recalcitrant industrial Keep up to date relations and climate policies, but the mythical Sign in or register to receive email alerts when new split between economy and environment has articles on your favourite topics or contributors are been perpetuated within his administration. published. Grab our main RSS feed or choose a topic-specific RSS Whereas attempts to reconcile economy and feed to keep up to date. (What's RSS?) climate have been undertaken in the UK by integrating the Energy and Climate Change Tags: oil and gas industry martin Follow us on Twitter. ministries, and in the US by appointing a Climate ferguson laurie ferguson forest conservation ets environmental issues and Energy Czar, Australia has set itself up for emissions trading scheme declan kuch failure with two ministers with entirely opposing climate change australian greenhouse worldviews — Resources and Energy Minister office andrew ferguson Martin Ferguson and Environment Minister Peter Garrett — pulling in different directions. -

Chapter Six Chatswood’S ‘Retail Battleground’ and the Concentration of Big Retail in the Post-War Period

Chapter Six Chatswood’s ‘Retail Battleground’ and the Concentration of Big Retail in the Post-War Period The repositioning of shopping centres as consumer oriented leisure precincts in the 1980s, demonstrated the industry’s ability to reinvent the superstructure of its model. It still relied on anchors, tenant mix, air-conditioning, parking, centralised management and coordinated marketing, but the range and type of anchors was expanded, and the link between retail consumption and entertainment made more explicit. The latter can also be read as a response to increasing competition within the industry. As we will see in Chapter Eight, there were widespread claims of retail saturation by the 1980s, with shopping centres increasingly taking business away from one another. The cosmetic and tenancy changes we traced in the previous chapter can be seen most simply as attempts to make centres more attractive to prospective customers – attempts that were conditioned by technological developments, changing markets, business opportunities, and the retail milieu of the time. Over the course of the post-war period, many of the old retail family companies disappeared or were absorbed by stronger rivals. Retail became increasingly corporatised and concentrated. One theme of this chapter is the competition between big retailers and their takeover battles of the 1980s. These are explored through the contest between David Jones and Grace Bros over the development of Chatswood Chase. The other theme is traffic congestion in and around shopping centres. With the vast majority of shopping trips in the 1980s made by car, traffic in areas such as Chatswood became a significant planning problem. -

Legislative Assembly

5493 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thursday 26 September 2002 ______ Mr Speaker (The Hon. John Henry Murray) took the chair at 10.00 a.m. Mr Speaker offered the Prayer. RIGHT TO SELF-DEFENCE (IMMUNITY FROM CIVIL LIABILITY) BILL Bill introduced and read a first time. Second Reading Mr HARTCHER (Gosford) [10.05 a.m.]: I move: That this bill be now read a second time. The Right to Self-defence (Immunity from Civil Liability) Bill will ensure that people who exercise their right to self-defence cannot thereafter be subject to legal action in the civil courts for damages. The bill is a simple bill. Clause 1 sets out the short title. Clause 2 provides for the commencement of the proposed Act on the date of assent. It further provides that the bill is not to be retrospective. It will not, therefore, apply to conduct carried out before the commencement of the Act. Clause 4 sets out the requirements for self-defence before immunity from civil liability is made good. Clause 4 spells out what constitutes self-defence for the purposes of the Act. Clause 4 states: (1) For the purposes of this Act, a person carries out conduct in self-defence if and only if the person believes the conduct is necessary: (a) to defend himself or herself or another person, or (b) to prevent or terminate the unlawful imprisonment of himself or herself or another person, or (c) to prevent property from unlawful appropriation, destruction, damage or interference, or (d) to prevent criminal trespass, or (e) to remove from any land or premises a person who is committing a criminal trespass and the conduct is a reasonable response in the circumstances as he or she perceives them. -

Craig Mcgregor'^

uQp HEADUNERS -> NtnHTCuvEl" 1! hers pot, piU with a inetre-high black-and-white 'mcKieni hriv-uia^i. inn rhjlii rui\\ • portrait of Frank Sinatra on the wa mp stretcher where he lakes I I f ^^ it'ter-lunch nap ("turns one day .vo. look at Ronald Reagan!"). a Craig McGregor'^ih y window, a tiny desk littered w iih scripts and scribbled notes and a I having a hau- wall of press pix of Clive with glam ng) and strives orous women : Joan Collins, Judy Social Portraits iisity of a man Green. Selina Scott... It is all part of , iias wasted half his un.spt>ih Aussie ockerside, which \ plause and a fal six-figuie BBC con- his life and wants to make eveiy has given liim the immense aclva j trace in his pockeL How does he get .second count form now on. tage on British television < [ away with it? being the Outsider "In many ways I've already lived around in sha(j The answer is a complex paradigm ray life, had a lot of fun. 1 really what menswearcircJ [ of how the media works in the lale to get on with nty work, try to do mincmc ij I twentieth century, beciuse Clive something useful in the years that are Hug [ James is obviously better and smarter remaining," he says with unexpected I and funnier than the amiable bufoon somlireness (he tunied .50 in IWO). I he portrays on the box. Indeed there rm really good for the work 1 do and CLIVE JAMES Fare many Clive James.