Basket Weavers and True Believers the Middle Class Left and the ALP Leichhardt Municipality C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linda Scott for Sydney Strong, Local, Committed

The South Sydney Herald is available online: www.southsydneyherald.com.au FREE printed edition every month to 21,000+ regular readers. VOLUME ONE NUMBER FORTY-NINE MAR’07 CIRCULATION 21,000 ALEXANDRIA BEACONSFIELD CHIPPENDALE DARLINGTON ERSKINEVILLE KINGS CROSS NEWTOWN REDFERN SURRY HILLS WATERLOO WOOLLOOMOOLOO ZETLAND RESTORE HUMAN RIGHTS BRING DAVID HICKS HOME New South Wales decides PROTEST AT 264 PITT STREET, CITY The South Sydney Herald gives you, as a two page insert, SUNDAY MARCH 25 ✓ information you need to know about your voting electorates. PAGES 8 & 13 More on PAGE 15 Water and housing: Labor and Greens Frank hits a high note - good news for live music? go toe to toe John Wardle Bill Birtles and Trevor Davies The live music scene in NSW is set to receive a new and much fairer regu- Heffron Labor incumbent Kristina latory system, after Planning Minister Keneally has denied that the State Frank Sartor and the Iemma Govern- government’s promised desalination ment implemented amendments to plant will cause road closures and the Local Government Act including extensive roadwork in Erskineville. a streamlined process to regulate Claims that the $1.9 billion desalina- entertainment in NSW and bring us tion plant at Kurnell will cause two more into line with other states. years of roadworks across Sydney’s Passed in the last week of Parlia- southern suburbs were first made by ment in November 2006, these the Daily Telegraph in February. reforms are “long overdue, and State government plans revealed extremely good news for the live that the 9 km pipeline needed to music industry” says Planning connect the city water tunnel with the Minister Frank Sartor. -

I Am Writing to Report on the Outcomes of The

28 July 2009 Mr Barry Cotter Chair: Sydney Airport Community Forum The Hon Anthony Albanese MP Ms Maria Patrinos Minister for Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government Community Representative Parliament House Mr Kevin Hill CANBERRA ACT 2600 Community Representative The Hon John Murphy MP Federal Member for Lowe The Hon Tanya Plibersek MP Dear Minister Federal Member for Sydney The Hon Peter Garrett MP I am writing to report on the outcomes of the meeting of the Sydney Federal Member for Kingsford-Smith th Airport Community Forum (SACF) held on Friday 10 of July 2009. The Hon Tony Burke MP Federal Member for Watson Members discussed the issue of the second airport for Sydney and The Hon Robert McClelland MP indicated they would appreciate your advice on whether the Federal Member for Barton Government’s policy is for the second airport to be within the Sydney The Hon Joe Hockey MP Federal Member for North Sydney Basin. The Hon Maxine McKew MP Federal Member for Bennelong The Forum expressed interest in the discussion paper ‘Safeguards for The Hon Dr Brendan Nelson MP airports and the communities around them’ recently released by the Federal Member for Bradfield Government. In particular members were concerned that penetrations The Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP of the Sydney Airport Obstacle Limitation Surface (OLS) by new Federal Member for Wentworth buildings may restrict long term options for sharing noise through the Mr Scott Morrison MP Federal Member for Cook spreading of flight paths. The Hon Kristina Keneally MP State Member for Heffron During discussions on the Runway End Safety Area (RESA) project The Hon Frank Sartor MP there was broad agreement that Mode 15 has been a positive addition State Member for Rockdale to the suite of noise sharing modes available under the Airport’s Long The Hon Carmel Tebbutt MP Term Operating Plan (LTOP). -

A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left

A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left http://www.softdawn.net/Archive/MRM/thecall.html September 1975 Melbourne Revolutionary Marxists Introduction (2017) by Robert Dorning and Ken Mansell Momentous changes occurred in Western societies in the 1960s and 70s. A wave of youth radicalisation swept many Western countries. Australia was part of this widespread generational change. The issues were largely common, but varied in importance from country to country. In Australia, the Vietnam War and conscription were major issues. This radicalisation included the demand for major political change, and new political movements and far-left organisations came into being. A notable new development in Australia was the emergence of Trotskyist groupings. However, as the wider movement subsided with Australia's withdrawal from the Vietnam War, the Australian Left became fragmented and more divided than ever. It was in this environment that, in 1975, "A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left" was published by the "Melbourne Revolutionary Marxists" (MRM). "The Call" includes a description of the evolution of the new Left movements in Australia including the Trotskyist current to which MRM belonged. MRM was a break-away from the Communist League, an Australian revolutionary socialist organisation adhering to the majority section of the Fourth International. At the Easter 1975 National Conference, virtually the entire Melbourne branch of the CL resigned en masse from the national organisation. The issue was the refusal of the national organisation to accept the application by Robert Dorning (a leading Melbourne member) for full membership on the grounds he held a "bureaucratic collectivist" position on the social nature of the Soviet Union, rather than the orthodox Trotskyist position of "deformed workers' state". -

100187168.Pdf

Museum ^^ oZ-yy,^ '<?/, V \ 1869 THE LIBRARY American Museum of Natural Grapevine History VOL. XXXVI, NO. 1 FEBRUARY, 1979 Norman D. Newell, Invertebrates, receives the Museum's Gold A magnificent bronze sculpture of Gardner D. Stout, past presi- Medal for Distinguished Achievement in Science from Robert G. dent, right, was unveiled at the Board of Trustees' Annual Meet- Goelet, president, at a special ceremony following the Annual ing by Thomas D. Nicholson, director, center. The work was Meeting of the Board of Trustees on November 27. A well-known created by artist Eliot Goldfinger, Exhibition, left, and will appear paleontologist. Dr. Newell joined the AMNH in 1945, becoming a in the annual exhibit of the National Academy of Design. curator emeritus in 1977. ' FLEX TIME DEEMED SUCCESS 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., but are able to choose which of the flexible hours they wish to work, as long as they put Early in 1978, the Museum introduced flex time, a in a full 70 hours during each two-week pay period and modern system of flexible working hours, in three de- the departments are adequately covered. partments. Under the guidance of Geraidine M. Smith, "The program provides employees with two things," Personnel Manager, the pilot program was put into says Geraidine Smith. "One is OfDportunity for flexi- effect in Ichthyology, Natural History Magazine, and bility and the other is responsibility." The employee the American Museum—Hayden Planetarium. Ichthy- keeps track of the number of hours worked with the ology was chosen as representative of the many sci- help of an individual time accumulator. -

Fourteen Studies in Qorporate Crime Or Corporate Harm. STAINS on a WHITE COLLAR Mmmmik Ikim

Chris Masters Fourteen studies in qorporate crime or corporate harm. STAINS ON A WHITE COLLAR mmmmik IKiM [Fmj^iBBou UiB^BB^ to Edited by Peter Grabosky and Adam Sutton Foreword by Chris Masters THE FEDERATION PRESS Published in Sydney by The Federation Press 101A Johnston Street Annandale. NSW. 2038 In association with Bow Press Pty Ltd 208 Victoria Road Drummoyne. NSW. 2047 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Stains on a white collar: fourteen studies in corporate crime or corporate harm. Bibliography. ISBN 1 86287 009 8. 1. Commercial crimes — Australia — Case studies. 2. Corporations — Australia — Corrupt practices — Case studies. 3. White collar crimes — Australia — Case studies. I. Grabosky, Peter N. (Peter Nils), 1945- . II. Sutton, Adam Crosbie. 364.1'68'0994 Copyright ® this collection The Australian Institute of Criminology This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Cover designed by Hand Graphics Text designed by Steven Dunbar Typeset in 10 pt Century Old Style by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough Printed in Australia by Griffin Press Production by Vantage Graphics, Sydney CONTENTS FOREWORD ix CHRIS MASTERS INTRODUCTION xi 1 THE BOTTOM OF THE HARBOUR TAX EVASION -

Full Day Hansard Transcript (Legislative Assembly, 11 May 2011, Corrected Copy) Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday, 11 May 2011

Full Day Hansard Transcript (Legislative Assembly, 11 May 2011, Corrected Copy) Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday, 11 May 2011. GOVERNOR'S SPEECH: ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Fourth Day's Debate Debate resumed from an earlier hour. Mr GUY ZANGARI (Fairfield) [6.17 p.m.] (Inaugural Speech): Mr Deputy-Speaker, I congratulate you on your election as the Deputy-Speaker. We look forward to your distinguished service to the House and to the people of New South Wales. It is a privilege to address the House this evening. It is a sincere honour to be elected to the oldest Parliament in the country and the Fifty-fifth Parliament of New South Wales. It is equally an honour to be the elected representative for Fairfield. Life's journey is characterised by the people you meet and the family you are part of. People are shaped and formed by their experiences throughout life, and I need to thank many people for shaping and moulding me into the person I am today. My life has been an experience of two halves. The first is to have grown up in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney with my parents and siblings; the second is to have been tertiary educated and to work, live and raise a family in the outer-western Sydney suburbs. I am always a westie and proud of it. I begin by acknowledging the people who assisted the Fairfield Labor Party campaign. My campaign director, Adrian Boothman, is a former student of Patrician Brothers' College, Fairfield. His tireless efforts, constant support and advice were and remain invaluable. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

Full Thesis Draft No Pics

A whole new world: Global revolution and Australian social movements in the long Sixties Jon Piccini BA Honours (1st Class) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of History, Philosophy, Religion & Classics Abstract This thesis explores Australian social movements during the long Sixties through a transnational prism, identifying how the flow of people and ideas across borders was central to the growth and development of diverse campaigns for political change. By making use of a variety of sources—from archives and government reports to newspapers, interviews and memoirs—it identifies a broadening of the radical imagination within movements seeking rights for Indigenous Australians, the lifting of censorship, women’s liberation, the ending of the war in Vietnam and many others. It locates early global influences, such as the Chinese Revolution and increasing consciousness of anti-racist struggles in South Africa and the American South, and the ways in which ideas from these and other overseas sources became central to the practice of Australian social movements. This was a process aided by activists’ travel. Accordingly, this study analyses the diverse motives and experiences of Australian activists who visited revolutionary hotspots from China and Vietnam to Czechoslovakia, Algeria, France and the United States: to protest, to experience or to bring back lessons. While these overseas exploits, breathlessly recounted in articles, interviews and books, were transformative for some, they also exposed the limits of what a transnational politics could achieve in a local setting. Australia also became a destination for the period’s radical activists, provoking equally divisive responses. -

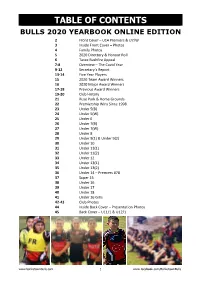

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS BULLS 2020 YEARBOOK ONLINE EDITION 2 Front Cover – U14 Premiers & U7/W 3 Inside Front Cover – Photos 4 Family Photos 5 2020 Directory & Honour Roll 6 Taree Bushfire Appeal 7-8 Overview – The Covid Year 9-12 Secretary’s Report 13-14 Five Year Players 15 2020 Team Award Winners 16 2020 Major Award Winners 17-18 Previous Award Winners 19-20 Club History 21 Ruse Park & Home Grounds 22 Premiership Wins Since 1998 23 Under 5(B) 24 Under 5(W) 25 Under 6 26 Under 7(B) 27 Under 7(W) 28 Under 8 29 Under 9(1) & Under 9(2) 30 Under 10 31 Under 11(1) 32 Under 11(2) 33 Under 12 34 Under 13(1) 35 Under 13(2) 36 Under 14 – Premiers #78 37 Super 15 38 Under 16 39 Under 17 40 Under 18 41 Under 16 Girls 42-43 Club Photos 44 Inside Back Cover – Presentation Photos 45 Back Cover – U11/1 & U12/1 www.bankstownbulls.com 1 www.facebook.com/BankstownBulls 2020 YEARBOOK FAMILY PHOTOS www.bankstownbulls.com 4 www.facebook.com/BankstownBulls 2020 DIRECTORY & HONOUR ROLL 2020 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE CBDJRL CLUB’S CLUB OF THE YEAR President: Ali Mehanna 2019 Bankstown Bulls (inaugural winner) Secretary: Matthew O’Neill MAJOR SPONSOR Treasurer: Rabab Raad Bankstown RSL Club Senior Vice President: Stan Hetaraka Assistant Secretary: Anthony Samuel SCOREBOARD SPONSOR First Option Bank 2020 GENERAL COMMITTEE Junior Vice President: David Tarabay JERSEY SPONSORS Canteen: Sandra Chahine Bankstown RSL Club / Star Buffet Bankstown Legal & Covid Officer: Hussein Dia Mortimer Apparel Cedar Beverages DELEGATES TO CBDJRL & BULLDOGS Ground King Civil Matthew O'Neill; -

122 DAYS to Engage with the Coalition, If You Comments Create a Misconception to 2013 Haven’T Already – We Can Help with This

THE POLICY UPDATE 1 | M a y 2013 CLIMATE GAMIFICATION …by CEO, Benjamin Haslem THE POLICY UPDATE The Climate Reality Project, founded and Members get bonus points when Earlier this year we released our first chaired by former US Vice President Al someone responds to a pasted comment newsletter, The Shell, under our new Gore, has decided to take on their and clicks back to Reality Drop. brand – Wells Haslem Strategic Public opponents at their own game and have Supporters say Reality Drop uses Affairs. We intend to publish it at least established an intriguing digital project: competitive gaming techniques to twice a year. Reality Drop. combat climate denial online. Just to make sure that we bring you as Peruse most online articles about climate It could provide an interesting model for much news as possible about what we are change, where people are invited to leave political parties during election up to and what has piqued our interest, comments, and you would be excused for campaigns. All sides of politics accuse the we’ve decided to create The Shell Policy thinking a large number of people not other parties of flooding online Update… a smaller version of The Shell only dismiss the reality or threat of man- comments with information critical of published every few months. made climate change but seem to be their opponents. Here is the first edition. Feel free to quite knowledgeable about it. Of course, this begs the question, is provide feedback and some of your They sprout all sorts of facts and figures Reality Drop any different from the very information, anecdotes and ideas for the and present unsubstantiated claims to people it is criticising? It too is providing next edition of the Policy Update. -

Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 The Registered Clubs Association of NSW ABN 61 724 302 100 ClubsNSW Level 8, 51 Druitt Street Sydney NSW 2000 Annual Report 02 9268 3000 www.clubsnsw.com.au 2017 AR Covers.indd 4 30/08/2017 12:07:10 PM Contents Our Purpose Contents & the Way We Work Overview 02. Our Purpose & the Way We Work Our purpose is to create opportunities for our 04. Chairman’s Review members to thrive. 08. From the CEO Board of Directors The way we work … 10. 12. Public Affairs 1. We treat people fairly, respecting their views 14. Workplace Relations and valuing their contributions. 16. Member Services & Marketing 18. Finance & Administration 2. We accept, embrace and promote diversity 20. ClubKENO Holdings Board of Directors and inclusivity. 3. We encourage our people to be creative, Financial Reports take initiative, show leadership and reach 21. Financial Reports Introduction their potential. 22. Directors’ Report 24. Accounting Officer’s Report 4. We take responsibility for our communications, 25. Statements of Profit or Loss decisions, actions and performance. and other Comprehensive Income 5. We act with integrity in our work and in dealing 26. Statements of Changes in Equity with others. 27. Statements of Financial Position 28. Statements of Cash Flows 29. Notes to the Financial Statements 56. Independent Auditor’s Report Supplements 58. State Councillors 59. Member Clubs 67. Affiliated Associations 68. ClubsNSW Community Partners 69. ClubsNSW Corporate Partners 70. ClubsNSW Industry Supporters CREDITS: EDITOR Darren Flynn | DEPUTY EDITOR Ben Rossleigh | CREATIVE MANAGER John Hewitt | AGENCY MKTG PHOTOGRAPHY Ben Symons Photography | PRINTER Pegasus Printing | DISTRIBUTION The Pack Factory Annual Report 2017 | 3 w Chairman’s Review Chairman’s Review Peter Newell OAM - Chairman lubsNSW has completed a year in competition for a range of new features and of competition for services. -

Australian Broadcasting Authority

Australian Broadcasting Authority annual report Sydney 2000 Annual Report 1999-2000 © Commonwealth of Australia 2000 ISSN 1320-2863 Design by Media and Public Relations Australian Broadcasting Authority Cover design by Cube Media Pty Ltd Front cover photo: Paul Thompson of DMG Radio, successful bidder for the new Sydney commercial radio licence, at the ABA auction in May 2000 (photo by Rhonda Thwaite) Printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, NSW For inquiries about this report, contact: Publisher Australian Broadcasting Authority at address below For inquiries relating to freedom of information, contact: FOi Coordinator Australian Broadcasting Authority Level 15, 201 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: (02) 9334 7700 Fax: (02) 9334 7799 .Postal address: PO Box Q500 Queen Victoria Building NSW 1230 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.aba.gov.au 2 AustJt"aHan Broadcasting Authority Level 1 S Darling Park 201 Sussex St Sydney POBoxQ500 Queen Victoria Building August 2000 NSW1230 Phone (02) 9334 7700 Fax (02) 9334 7799 Senator the Hon. RichardAlston E-mail [email protected] 'nister for Communications,Information Technology and the Arts DX 13012Marlret St Sydney liarnentHouse anberraACT 2600 In accordancewith the requirements of section 9 andSchedule 1 of the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997, I ampleased to present, on behalfof the Members of the AustralianBroadcasting Authority, thisannual reporton the operations of the llthorityfor the year 1999-2000. Annual Report 1999-2000 4 Contents Letter of transmittal 3 Members' report