Dairy Deregulation an Australian Journey in Structural Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformative Change in Contemporary Australian Agriculture

Transformative change in contemporary Australian agriculture Katrina Sinclair B Sc Agr (Sydney) M Rur Sc (UNE) A thesis submitted to Charles Sturt University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Environmental Sciences Faculty of Science October 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES....................................................................................................................v LIST OF TABLES..................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF BOXES ..................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF ACRONYMS............................................................................................................ viii GLOSSARY .............................................................................................................................ix Certificate of Authorship............................................................................................................x Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................xi PUBLICATIONS ARISING FROM THIS RESEARCH............................................................ xii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................ xiii Chapter One Introduction..........................................................................................................1 -

Hansard 22 June 2000

22 Jun 2000 Legislative Assembly 1849 THURSDAY, 22 JUNE 2000 clear signals to industry, encouraging diversification of our energy sector towards a balanced energy mix. The past has been coal. The future, as Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) the policy spells out, must be coal, gas and read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. renewables. The Government is actively pursuing the development of gas-fired power stations across the State. Cabinet will soon be GLOBAL CHALLENGE in a position to consider options to develop Mr SPEAKER: Order! I remind all gas-fired generation facilities in Townsville. We honourable members of today's launch of the have also achieved good progress in seven-day global challenge in the former negotiations with AGL/Petronas to advance Legislative Council Chamber at 12.15 p.m. I construction of the Gladstone-Townsville join the Premier and the Leader of the section of the PNG gas pipeline. Opposition in encouraging all members to I am pleased to advise the House today support the challenge and take part in today's that our energy policy has brought another launch. gas-fired power station to fruition. Later today, Energy Minister Tony McGrady, Treasurer AUDITOR-GENERAL'S REPORT David Hamill and I will announce Government approval for the construction of a $250m gas- Mr SPEAKER: Honourable members, I fired power station at Swanbank near Ipswich. have to report that today I received from the The 385 megawatt facility will expand the Auditor-General a report titled Audit Report existing Swanbank Power Station and form the No. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Images Catalogue Last Updated 15 Mar 2018

Images Catalogue Last Updated 15 Mar 2018 Record Title Date Number P8095 1st 15 Rugby Union team photo [Hawkesbury Agricultural College HAC] - WR Watkins coach 11/04/1905 P2832 3 Jersey "Matrons" held in paddock below stud stock shed for student demonstrations - Colo breed on right [Hawkesbury 30/04/1905 Agricultural College (HAC)] P8468 3 students perform an experiment at UWS Nepean Science fair for gifted & talented students - 1993 1/06/1993 P8158 3 unidentified people working at a computer in lab coats 14/06/1905 P8294 3D Illustrations at Werrington - VAPA 1/06/1992 P8292 3rd year Communications students under the "tent" - Alison Fettell (Left) & Else Lackey 27/10/1992 P8310 3rd year computer programming project 14/06/1905 P1275 4th Cavalry Mobil Veterinary Section [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] 21/04/1905 P2275 4th Cavalry Mobile Veterinary Section [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] 21/04/1905 P6108 5 boys playing basketball 14/05/1905 P1683 60 colour slides in a folder - these slides were reproduced in publicity brochures and booklets for Hawkesbury Agricultural 2/06/1905 College - Careers in Food Technology [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P6105 7 boys playing Marbles 14/05/1905 P1679 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (1 of 9) - B Doman (Principal) 18/03/1966 giving speech from podium [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P1809 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (2 of 9) - Three men 18/03/1966 (unidentified) [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P1810 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (3 of 9) - Speaker at podium 18/03/1966 [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P1811 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (4 of 9) - The Hon. -

MS 65 Papers of Studio One

MS 65 Papers of Studio One Summary Administrative Information Scope and Content Biographical Note Series List and Description Box Description Folder Description Summary Creator: Studio One staff Title: Papers of Studio One Date range: 1985-2000 Reference number: MS 65 50 Boxes + 13 ring binders + 1 oversized Extent: box Administrative Information Access See National Gallery of Australia Research Library reference desk librarians. Provenance The papers were salvaged by Roger Butler, Senior Curator of Australian Prints and Drawing at the National Gallery of Australia in early 2000 after they were had been assigned for disposal. Scope and Content Series 1 of the collection comprises 42 boxes of material directly related to the administrative functions of a small, Canberra based, print editioning organisation and spans 17 years from 1985 to 2002. Within this series are 13 ring binders that contain a variety of media including negatives, photographs, slides and prints. Included in this series is an oversized box containing outsized material. Series 2 consists of financial records. The collection content includes correspondence; funding applications; board meeting agendas and minutes; reports; job cards (print editioning forms) and printing contracts, with financial records in the second series. Various artists represented in the National Gallery of Australia Collection used the Studio One editioning services. These include George Gittoes, Rosalie Gascoigne, Dennis Nona, Treahna Hamm, Jane Bradhurst, Pamela Challis, Ray Arnold, Lesbia Thorpe (Lee Baldwin) and Bruno Leti. This collection also documents, through records of correspondence, workshop details and job cards, the development of relationships with Indigenous artists through print workshops and print editioning as convened by Theo Tremblay and Basil Hall, including Melville Island, Munupi Arts and Crafts, Cairns TAFE, and Turkey Creek. -

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

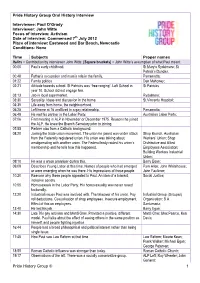

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

The Essay Prepared by Historian Professor Paul Ashton

1987: The Year of New Directions RELEASE OF 1987 NSW CABINET PAPERS Release of 1987 NSW Cabinet Papers 2 Table of Contents 1987: The Year of New Directions ......................................................................................................... 3 Dual Occupancy and the Quarter-acre Block ...................................................................................... 4 The Sydney Harbour Tunnel ................................................................................................................ 5 The Bicentenary .................................................................................................................................. 6 Sydney City Council Bill ....................................................................................................................... 6 The University of Western Sydney ...................................................................................................... 7 Casino Tenders .................................................................................................................................... 8 Chelmsford Private Hospital ............................................................................................................... 9 Workers’ Compensation ................................................................................................................... 10 Establishment of the Judicial Commission ........................................................................................ 10 1987 NSW Cabinet ............................................................................................................................... -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright ‘When the stars align’: decision-making in the NSW juvenile justice system 1990-2005 Elaine Fishwick A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education and Social Work University of Sydney 2015 Faculty of Education and Social Work Office of Doctoral Studies AUTHOR’S DECLARATION This is to certify that: I. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the <insert Name of Degree> Degree II. -

Legislative Assembly

2669 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Friday 17 June 2011 __________ The Speaker (The Hon. Shelley Elizabeth Hancock) took the chair at 10.00 a.m. The Speaker read the Prayer and acknowledgement of country. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Routine of Business Mr BRAD HAZZARD (Wakehurst—Minister for Planning and Infrastructure, and Minister Assisting the Premier on Infrastructure NSW) [10.00 a.m.]: Normally at this time the House would deal with General Business Notices of Motions (for Bills) and debate General Business Notices of Motions. However, this morning the Government has consented to the member for Northern Tablelands moving General Business Notice of Motion (General Notices) No. 15. Members are aware of the need to get deal with Government Business in order to get certain bills passed and sent to the Legislative Council. I thank the Opposition for its cooperation to date in that respect. Mr Michael Daley: But you are going to do us over anyway. Mr BRAD HAZZARD: I prefer to think of it as a partnership in the great effort of democracy, and I am heartened that the member for Maroubra wants to make New South Wales number one again given that for 16 years Labor did everything it could to ensure that it was not. Between 10.00 a.m. and 10.30 a.m. no divisions can be called, so I will not attempt to move the suspension of standing orders to facilitate Government business coming on at the conclusion of debate on the motion of the member for Northern Tablelands. It seems that the member for Maroubra is not as obliging this morning as he has been in the past. -

New South Wales Election 1999 ISSN 1328-7478

Department afthe Parliamentary Library !1lJi INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES ~)~~~~~~~~~(.Co!" Research Paper No. 22 1998-99 New South Wales Election 1999 ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no pall of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Depattment of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members ofthe public. Published by the Depattment ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 22 1998-99 New South Wales Election 1999 Scott Bennett Politics and Public Administration Group Gerard Newman Statistics Group 8 June 1999 Acknowledgments The author would like to thank C. -

APR 2016-07 Winter Text FA2.Indd

Printer to adjust spine as necessary Australasian Parliamentary Review Parliamentary Australasian Australasian Parliamentary Review JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP Editor Colleen Lewis Modernising parliament for future generations AUTUMN/WINTER 2016 Minority government: a backbench and crossbench perspective Parliamentary committees connecting with the public • VOL 31 NO 1 31 VOL AUTUMN/WINTER 2016 • VOL 31 NO 1 • RRP $A35 AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP (ASPG) AND THE AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW (APR) APR is the official journal of ASPG which was formed in 1978 for the purpose of encouraging and stimulating research, writing and teaching about parliamentary institutions in Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific Membership of the Australasian Study of (see back page for Notes to Contributors to the journal and details of AGPS membership, which includes a subscription to APR). To know more about the ASPG, including its Executive membership and its Chapters, Parliament Group go to www.aspg.org.au Australasian Parliamentary Review Membership Editor: Dr Colleen Lewis, [email protected] The ASPG provides an outstanding opportunity to establish links with others in the parliamentary community. Membership includes: Editorial Board • Subscription to the ASPG Journal Australasian Parliamentary Review; Dr Peter Aimer, University of Auckland Dr Paul Reynolds, Parliament of Queensland • Concessional rates for the ASPG Conference; and Dr David Clune, University of Sydney Kirsten Robinson, Parliament of Western Australia • Participation in local Chapter events. Dr Ken Coghill, Monash University Kevin Rozzoli, University of Sydney Rates for membership Prof. Brian Costar, Swinburne University of Technology Prof. Cheryl Saunders, University of Melbourne Dr Jennifer Curtin, University of Auckland Emeritus Prof. -

Port-Oriented Coal Transport Infrastructure: an Analysis of Locational Decision-Making

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1984 Port-oriented coal transport infrastructure: an analysis of locational decision-making Sophia Apolonia Everett University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Everett, Sophia Apolonia, Port-oriented coal transport infrastructure: an analysis of locational decision- making, Master of Arts thesis, Department of Geography, University of Wollongong, 1984.