After the Towers: the Destruction of Public Housing and the Remaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Alternatives by Time Period" Is Broken Apart Into Subjects and ALL the Titles I've Found So Far, with Their Reading Levels

HISTORY READING ALTERNATIVES PDF: Caswell 3 Laura Berquist approved sharing this list but because she hasn't reviewed all of these books, she just wanted to make sure it was made clear that it's the work of Deanna Caswell, not MODG. Deanna created lists of all the history books in the 2nd - 5th grade MODG history lesson plans determining reading levels by using what her home state of TN uses: AcceleratedReader level, http://www.arbookfind.com/ . Then she researched alternatives for students who are struggling or want something more advanced. She explains below what the document covers. I think you'll find it very helpful when you're trying to see the grade level for which a particular book is written. If your child is struggling w/the suggested book, you can look for a book more in line w/his reading ability. It's good to have a mix of challenging reads and easy reads. If you are busy and neither you nor an older sibling can sit down to read a suggested book, you can find an alternative book that the child can read. **** The list "MODG Recommendations" is the reading levels for all the books in the syllabi, her originals and alternatives. This is so the parent can identify HER recommendations first and see if they are in the child's level. The lists are long because Laura recommends some series. It's ONLY Laura's listed books. Bolded titles are the ones in the lesson plans. Not-bolded are the one she lists as alternatives and are not in the lesson plans. -

(“Dpd”) on Behalf of the Chicago Housing Authority (“Cha”) Request for Proposals (“Rfp”) For

CITY OF CHICAGO - DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT (“DPD”) ON BEHALF OF THE CHICAGO HOUSING AUTHORITY (“CHA”) REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (“RFP”) FOR THREE CABRINI-GREEN DEVELOPMENT PARCELS ISSUED ON: THURSDAY, DECEMBER 31, 2015 ISSUED BY: THE CHICAGO DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ON BEHALF OF THE CHICAGO HOUSING AUTHORITY PROPOSALS MAY BE RECEIVED PRIOR TO, BUT NOT LATER THAN, JUNE 29, 2016 AT 1:00 PM, LOCAL TIME Sealed proposals must be received and time stamped no later than the date and time listed in the solicitation and submitted in sealed envelopes or packages. The outside of the envelope must clearly indicate the Respondent name and address, name of the project, the time and date specified for receipt. PROPOSALS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED AFTER THE DUE DATE AND TIME. Respondent Name: Contact Name: ____________________________________________________ Contact Telephone: ____________________________________________________ Contact Email: ____________________________________________________ This selection process is unique to the Scope of Work described herein and notwithstanding any other proposal, qualification or bid requests provided by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development on behalf of the Chicago Housing Authority. Proposers must comply with the requirements as defined in this RFP. David L. Reifman, Commissioner Eugene Jones, Acting Chief Executive Chicago, Department of Planning and Development Chicago Housing Authority 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... -

ENTREPRENEURIAL EDGE Page 10

SPRING 2015 MAGAZINEM A G A Z I N E ENTREPRENEURIAL EDGE Page 10 HONOR ROLL OF DONORS Page 37 70505_co2.indd 1 3/31/15 7:10 PM 70505_co2.indd 2 3/31/15 7:10 PM Spring 2015, Volume 12, Number 01 CONTENTS CABRINI Magazine is published by the Marketing and Communications Office. 10 Feature: Entrepreneurial Edge Editor Cabrini alumni share stories Megan Maccherone of starting their own business Writers/Contributors Christopher Grosso Nicholas Guldin ’12 David Howell Lori Iannella ’06 Core Values Megan Maccherone 18 Rachel McCarter Highlights and updates of Cabrini’s Katie Aiken Ritter work for the greater good Photography Discovery Channel Nicholas Guldin ’12 Linda Johnson Kelly & Massa Jim Roese 37 2013-2014 Honor Roll of Donors Stuart Sternberg A special report honoring our donors Matthew Wright President Donald Taylor, Ph.D. Cabinet Beverly Bryde, Ed.D., Dean, Education Celia Cameron Vice President, Marketing & DEPARTMENTS Communications Brian Eury 2 Calendar of Events Vice President, Community Development & External Relations 3 From The President Jeff Gingerich, Ph.D. Interim Provost & Vice-President, 4 News On Campus Academic Affairs Mary Harris, Ph.D., 22 Athletics Interim Dean, Academic Affairs Christine Lysionek, Ph.D. 24 Alumni News Vice President, Student Life Eric Olson, C.P.A. 33 Class Notes Vice President, Finance/Treasurer Etc. Robert Reese 36 Vice President, Enrollment Pierce Scholars’ Food Recovery Management Susan Rohanna Human Resources Director George Stroud, Ed.D. On the Cover: Dean of Students Dave Perillo ‘00 prepares his talk to Cabrini design Marguerite Weber, D.A. Vice President, Adult & Professional students about being a freelance illustrator. -

Public Housing

On 12 June 2009, Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture convened a day-long policy and design workshop with students and faculty to investigate the need and the potential for public housing in the United States. The financial crisis added urgency to this effort to reinvigorate a long-dormant national conversation about publicPUBLIC housing, which remains the subject of unjust stigmas and unjustified pessimism. Oriented toward reframing the issue by imagining new possi- bilities,HOUSING: the workshop explored diverse combinations of architecture and urban policy that acknowledged the responsibilitiesA of Ngovernmentew and the limits of the private markets. Principles were discussed, ideas wereC tested,onversation and scenarios were proposed. These were distributed along a typical regional cross-section, or transect, representing a wide range of settlement patterns in the United States. The transect was broken down into five sectors: Urban Core, Urban Ring, Suburban, Exurban, and Rural. Participants were asked to develop ideas within these sectors, taking into account the contents of an informational dossier that was provided in advance. The dossier laid out five simple propositions, as follows: 1 Public housing exists. Even today, after decades of subsidized private homeownership, publicly owned rental housing forms a small but important portion of the housing stock and of the cultural fabric nationwide. 2 Genuinely public housing is needed now more than ever, especially in the aftermath of a mortgage foreclosure crisis and increasingly in nonurban PUBLIC areas. 3 Public infrastructure also exists, though mainly in the form of transportation and water utilities. HOUSING: 4 Public infrastructure is also needed. -

A Vision of Zion: Rendering Shows How Erased Black Cemetery Space

ERASED A vision of Zion: Rendering shows how erased Black cemetery space could be revitalized Architects have visualized what the space could look like, if given the opportunity to restore the area. Emerald Morrow | Published: 6:21 PM EDT September 18, 2020 TAMPA, Fla. — More than a year after a whistleblower led archaeologists to hundreds of graves from a segregation- era African American cemetery underneath a public housing development and two neighboring businesses in Tampa, architects have visualized what the space could look like, if given the opportunity to restore the area. Tampa Housing Authority Chief Operating Officer Leroy Moore said architects presented the rendering as an early visioning concept. While he reiterated it is not a final design, he said THA hopes to incorporate the land that comprises Zion Cemetery into the larger redevelopment proposal of Robles Park Village. In 2019, a Tampa Bay Times investigation revealed that hundreds of graves from Zion Cemetery were missing and suggested they could be underneath Robles Park Village, a public housing apartment complex located off N. Florida Avenue in Tampa. Ground-penetrating radar and physical archaeological digs later confirmed the presence of coffins underground. Radar images also confirmed graves on an adjacent towing lot and a property owned by local businessman Richard Gonzmart. In total, archaeologists detected nearly 300 graves from the cemetery. Since then, the Tampa Housing Authority formed a committee comprising housing authority leaders, residents and leaders from Robles Park, the NAACP and the city of Tampa. Archaeologists who worked on the investigation as well as lawmakers are also part of the group. -

Square Feet 150 N

7,196 Elegant Office Suite Available for Sublease Below Square Feet 150 N. Wacker Drive, Chicago, Illinois Market Rate Lease Information Building + Location Highlights • 11th floor: 7,196 RSF • Partial furniture can be made available • 2 blocks from Ogilvie Station and 5 blocks from Union Station • Available: Immediately • Rate: Negotiable • Term: June 30, 2019 • Conferencing facility and fitness center on site • Starbucks on the 1st floor Suite Highlights • Less than 0.5 miles from the Brown, • Modern office space with incredible • Exceptional views of skyline and Purple and Orange Line stops at natural light Chicago River Washington & Wells. VIEWS GREAT Opportunity Overview This stunning 7,196-sf, 11th floor office space is available for sublease. Located on the corner of Wacker and Randolph with easy access to the Metra and all that the Loop has to offer, the building houses a fitness center as well as a Starbucks on the ground floor. The partially-furnished space features a mixture of private offices and collaborative spaces, efficiently configured within a bright, traditional floor plan with views of the skyline and the Chicago River. Area Information Within walking 492 restaurants 10,276 businesses distance from and bars located with 285,125 Metra and CTA within 0.5 miles employees within 0.5 miles Floor Plan N Suite Photos Division Street (1200 N) 101 W. 1165 N. 45 W. 71 E. 1150 N. Lake Shore Drive Parkside of Old Town Seward 1155 N. P Elm Park P Tower 30 E. N Elm Street (1142 N) Atrium Elm Street (1142 N) Village St. Anthony’s 21-31 E. -

CHICAGO: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress

CHICAGO: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress A Guide and Resources to Build Chicago Progress into the 8th Grade Curriculum With Literacy and Critical Thinking Skills November 2009 Presenting sponsor for education Sponsor for eighth grade pilot program BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS “Our children must never lose their zeal for building a better world. They must not be discouraged from aspiring toward greatness, for they are to be the leaders of tomorrow.” Mary McLeod Bethune “Our children shall be taught that they are the coming responsible heads of their various communities.” Wacker Manual, 1911 Chicago, City of Possibilities, Plans, and Progress 2 More Resources: http://teacher.depaul.edu/ and http://burnhamplan100.uchicago.edu/ BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS Table of Contents Teacher Preview …………………………………………………………….4 Unit Plan …………………………………………………………………11 Part 1: Chicago, A History of Choices and Changes ……………………………13 Part 2: Your Community Today………………………………………………….37 Part 3: Plan for Community Progress…………………………………………….53 Part 4: The City Today……………………………………………………………69 Part 5: Bold Plans. Big Dreams. …………………………………………………79 Chicago, City of Possibilities, Plans, and Progress 3 More Resources: http://teacher.depaul.edu/ and http://burnhamplan100.uchicago.edu/ BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS Note to Teachers A century ago, the bold vision of Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s The Plan of Chicago transformed 1909’s industrial city into the attractive global metropolis of today. The 100th anniversary of this plan gives us all an opportunity to examine both our city’s history and its future. The Centennial seeks to inspire current civic leaders to take full advantage of this moment in time to draw insights from Burnham’s comprehensive and forward-looking plan. -

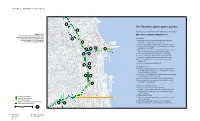

The Riverfront Open Space System 12 Planned, Proposed and Envisioned Riverfront Recommendations

CHAPTER 4 Waterfronts and Open Spaces 10 The Riverfront Open Space System 12 Planned, proposed and envisioned riverfront recommendations. Figure 4.3.23 KEY CHICAGO RIVER RECOMMENDATIONS The riverfront will become a major new public amenity on a par with the lakefront. A continuous riverwalk will extend from 11 NEAR NORTH outlying neighborhoods through the 10. Add a new boat house, pedestrian bridge and river edge Central Area to Lake Michigan 13 landscape at the North Avenue turning basin 11. Enhance landscaping along the west side of Goose Island 12. Create a natural habitat and recreation opportunities along the 15 16 14 east side of Goose Island 17 13. Ensure continuous river access through the Montgomery Ward site to connect with parks at Hobbie and Erie Streets. 19 18 14. Create Du Sable Park at the mouth of the Chicago River 15. Create an active riverwalk with commercial uses along the north side of the Main Branch from the lake to Wolf Point. 16. Create new public space at the Sun Times-Trump Tower Chicago site. 20 17. Create a new public park at Wolf Point. 21 22 THE EXPANDED LOOP 18. Create a continuous pedestrian riverwalk along Wacker Drive on the Main Branch from Lake Street to the lakefront as part of the Wacker Drive improvements. 19. Develop a riverfront plaza on the west bank of the South Branch 25 23 between Randolph and Lake Streets. 20. Develop a public riverfront plaza at 310 South Wacker Drive. 21. Create new riverfront open space at the Old Main Post Office along with its redevelopment. -

Champaign County

MARKET RATE (PRIVATE) HOUSING Champaign County Recognition Level: Silver 217 Midtown 202 E Green St, Suite 4 Champaign, IL 61820 217-355-8300 www.217midtown.com Management By: The Preiss Company Recognition Level: Silver 309 Green 309 E. Green St Champaign, IL 61820 217-366-3500 www.309green.com Management By: American Campus Communities Recognition Level: Silver 75 Armory 512 S. Neil St Champaign, IL 61820 217-356-3511 www.75armory.com Management By: Next Chapter Properties MARKET RATE (PRIVATE) HOUSING Lake County Recognition Level: Gold Deer Park Crossing 21599 W. Field Ct Deer Park, IL 60010 847-438-3850 [email protected] Management By: Deer Park Crossing Realty Recognition Level: Silver Capstone Quarters 1901-1905 N. Lincoln Ave. 217-367-7368 www.capstonequarters.com Management By: Green St Realty Recognition Level: Silver Eastview Apartments 806 W. Green Street Urbana, IL 61801 217-377-1197 www.eastview-apt.com Management By: Eastview Apartments Recognition Level: Silver Kellner Rental Properties P.O. Box 3402 Champaign, IL 61826 217-621-8388 www.kellner.managebuilding.com Management By: Kellner Rental Properties (KRP) MARKET RATE (PRIVATE) HOUSING Champaign County Recognition Level: Silver Loft 54 309 E. Green St., Suite 103 Champaign, IL 61820 217-366-3500 www.lofts54.com Management By: American Campus Communities Recognition Level: Silver Marshall Apartments 1911 Trout Valley Champaign, IL 61820 217-356-1407 www.champaignmarshallapartments.com Management By: Marshall Apartments Recognition Level: Silver Parkside Apartments 1205 E Florida Ave Urbana, IL 61802 217-344-2072 Management By: Parkside Apartments Recognition Level: Silver The Pointe at UI 1601 E. -

Development Framework

CHAPTER 4 Development Framework Chapter 4 : THEME 1 Development Framework Direct growth to create a dynamic Central Area made up of vibrant, mixed-use districts Final Report CHICAGO CENTRAL AREA PLAN DRAFT June 2003 43 CHAPTER 4 Development Framework Figure 4.1.1 The Expanded Loop Fig. 4.1.2 High-Density, Mixed-Use Corridors Fig. 4.1.3 Neighborhoods and Special Places Fig. 4.1.4 Landmark and Character Districts Fig. 4.1.5 Industrial Districts and Corridors Fig. 4.1.6 Cultural Attractions Fig. 4.1.7 Education and Learning and Tourist Destinations Final Report June 2003 DRAFT 44 CHAPTER 4 Development Framework Theme 1 Development Framework Direct growth to create a dynamic Central Area made up of vibrant, mixed-use urban districts Guiding Principles • THE EXPANDED LOOP Extend the highest density office core into the West Loop around transit stations, services and the Chicago River • HIGH-DENSITY, MIXED-USE CORRIDORS Develop high-density, mixed-use corridors which extend from the expanded Loop and are served by transit • NEIGHBORHOODS AND SPECIAL PLACES Support a diverse collection of livable neighborhoods and special places • LANDMARKS AND CHARACTER DISTRICTS Preserve and strengthen the Central Area's world-renowned architectural and cultural heritage • INDUSTRIAL DISTRICTS AND CORRIDORS Strengthen Industrial Corridors and Planned Manufacturing Districts • EDUCATION AND LEARNING Direct the growth of the Central Area's educational institutions and provide opportunities for lifelong learning • CULTURAL ATTRACTIONS AND TOURIST DESTINATIONS Promote and strengthen the Central Area’s world-class cultural assets The substantial growth projected for the Central Area requires a development framework to ensure that it remains a desirable office address and is livable, convenient and attractive. -

LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014

THE LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014 Mayor Rahm Emanuel City Hall - 121 N LaSalle St. Chicago, IL 60602 Dear Mayor Emanuel, As co-chairs of the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Site Selection Task Force, we are delighted to provide you with our report and recommendation for a site for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. The response from Chicagoans to this opportunity has been tremendous. After considering more than 50 sites, discussing comments from our public forum and website, reviewing input from more than 300 students, and examining data from myriad sources, we are thrilled to recommend a site we believe not only meets the criteria you set out but also goes beyond to position the Museum as a new jewel in Chicago’s crown of iconic sites. Our recommendation offers to transform existing parking lots into a place where students, families, residents, and visitors from around our region and across the globe can learn together, enjoy nature, and be inspired. Speaking for all Task Force members, we were both honored to be asked to serve on this Task Force and a bit awed by your charge to us. The vision set forth by George Lucas is bold, and the stakes for Chicago are equally high. Chicago has a unique combination of attributes that sets it apart from other cities—a history of cultural vitality and groundbreaking arts, a tradition of achieving goals that once seemed impossible, a legacy of coming together around grand opportunities, and not least of all, a setting unrivaled in its natural and man-made beauty. -

Lakeshore East Elementary School S

PUBLIC BUILDING COMMISSION OF CHICAGO 2009 YEAR END STAFF REPORTS Executive Summary Report Public Building Commission of Chicago Richard J. Daley Center 50 West Washington, Room 200 Chicago, Illinois 60602 Tel: 312-744-3090 Fax: 312-744-8005 Report Highlights – 2009 Year End 1. Letter from Executive Director, Executive Summary Report & 2009 Project Completion Map 2. 2009 Quarterly Program Forecast Report We have developed this report for quarterly distribution to the Board, our clients and our MBE/WBE Assistance Agencies as well as prospective bidders. 3. Market Conditions Report This graphic illustrates comparative costs of like buildings, thereby tracking recent changes in the market. 4. Program Cost Status Report Our current program authority exceeds $1.8 B in project development costs. Currently, we are under budget by 5.78%, representing $106.7 MM. 5. Monthly Project Status Report This report provides an individual detailed snapshot of every PBC project. 6. M/WBE Commitment Report 2009 Construction Projects by Type (GC, JOC, Special Projects and CM at Risk) Through Q4 2009, 14 contracts for General Construction (GC) projects valued at $167,367,593.00, 12 work orders for Job Order Contract (JOC) projects valued at $27,523,830.07, 2 work orders for Special projects valued at $11,233,528.17 and trade contracts for five CM at Risk contract valued at $5,824,766.72 have been awarded for a total value of $211,949,717.96. MBE commitment in GC projects awarded in 2009 was 28.84 % valued at $48,270,635.00 MBE commitment in JOC projects