Connecting People and Place Prosperity in Chicago's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(“Dpd”) on Behalf of the Chicago Housing Authority (“Cha”) Request for Proposals (“Rfp”) For

CITY OF CHICAGO - DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT (“DPD”) ON BEHALF OF THE CHICAGO HOUSING AUTHORITY (“CHA”) REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (“RFP”) FOR THREE CABRINI-GREEN DEVELOPMENT PARCELS ISSUED ON: THURSDAY, DECEMBER 31, 2015 ISSUED BY: THE CHICAGO DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ON BEHALF OF THE CHICAGO HOUSING AUTHORITY PROPOSALS MAY BE RECEIVED PRIOR TO, BUT NOT LATER THAN, JUNE 29, 2016 AT 1:00 PM, LOCAL TIME Sealed proposals must be received and time stamped no later than the date and time listed in the solicitation and submitted in sealed envelopes or packages. The outside of the envelope must clearly indicate the Respondent name and address, name of the project, the time and date specified for receipt. PROPOSALS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED AFTER THE DUE DATE AND TIME. Respondent Name: Contact Name: ____________________________________________________ Contact Telephone: ____________________________________________________ Contact Email: ____________________________________________________ This selection process is unique to the Scope of Work described herein and notwithstanding any other proposal, qualification or bid requests provided by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development on behalf of the Chicago Housing Authority. Proposers must comply with the requirements as defined in this RFP. David L. Reifman, Commissioner Eugene Jones, Acting Chief Executive Chicago, Department of Planning and Development Chicago Housing Authority 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... -

The Riverfront Open Space System 12 Planned, Proposed and Envisioned Riverfront Recommendations

CHAPTER 4 Waterfronts and Open Spaces 10 The Riverfront Open Space System 12 Planned, proposed and envisioned riverfront recommendations. Figure 4.3.23 KEY CHICAGO RIVER RECOMMENDATIONS The riverfront will become a major new public amenity on a par with the lakefront. A continuous riverwalk will extend from 11 NEAR NORTH outlying neighborhoods through the 10. Add a new boat house, pedestrian bridge and river edge Central Area to Lake Michigan 13 landscape at the North Avenue turning basin 11. Enhance landscaping along the west side of Goose Island 12. Create a natural habitat and recreation opportunities along the 15 16 14 east side of Goose Island 17 13. Ensure continuous river access through the Montgomery Ward site to connect with parks at Hobbie and Erie Streets. 19 18 14. Create Du Sable Park at the mouth of the Chicago River 15. Create an active riverwalk with commercial uses along the north side of the Main Branch from the lake to Wolf Point. 16. Create new public space at the Sun Times-Trump Tower Chicago site. 20 17. Create a new public park at Wolf Point. 21 22 THE EXPANDED LOOP 18. Create a continuous pedestrian riverwalk along Wacker Drive on the Main Branch from Lake Street to the lakefront as part of the Wacker Drive improvements. 19. Develop a riverfront plaza on the west bank of the South Branch 25 23 between Randolph and Lake Streets. 20. Develop a public riverfront plaza at 310 South Wacker Drive. 21. Create new riverfront open space at the Old Main Post Office along with its redevelopment. -

Our Great Rivers Vision

greatriverschicago.com OUR GREAT RIVERS A vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Our Great Rivers: A vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers Letter from Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel 4 A report of Great Rivers Chicago, a project of the City of Chicago, Metropolitan Planning Council, Friends of the Chicago River, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and Ross Barney Architects, through generous Letter from the Great Rivers Chicago team 5 support from ArcelorMittal, The Boeing Company, The Chicago Community Trust, The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation and The Joyce Foundation. Executive summary 6 Published August 2016. Printed in Chicago by Mission Press, Inc. The Vision 8 greatriverschicago.com Inviting 11 Productive 29 PARTNERS Living 45 Vision in action 61 Des Plaines 63 Ashland 65 Collateral Channel 67 Goose Island 69 FUNDERS Riverdale 71 Moving forward 72 Our Great Rivers 75 Glossary 76 ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT OUR GREAT RIVERS 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This vision and action agenda for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers was produced by the Metropolitan Planning RESOURCE GROUP METROPOLITAN PLANNING Council (MPC), in close partnership with the City of Chicago Office of the Mayor, Friends of the Chicago River and Chicago COUNCIL STAFF Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Margaret Frisbie, Friends of the Chicago River Brad McConnell, Chicago Dept. of Planning and Co-Chair Development Josh Ellis, Director The Great Rivers Chicago Leadership Commission, more than 100 focus groups and an online survey that Friends of the Chicago River brought people to the Aaron Koch, City of Chicago Office of the Mayor Peter Mulvaney, West Monroe Partners appointed by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, and a Resource more than 3,800 people responded to. -

T Ber Y Alen

TIM BER . T E C H N O L O G Y . T A L E N T Industrial warehouses are places of collaboration, creation, innovation. They embody entrepreneurship. T3 has all those characteristics, plus the efficiency and wellness characteristics of new construction. It is a workplace uniquely designed for recruitment and retention, by providing its occupants with a healthy empowering environment – a place where Chicago’s top innovators can find a home. CREATED BY HINES. T3 GOOSE ISLAND | CHICAGO, IL T3 RINO | DENVER, CO T3 BAYSIDE | TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA T3 MINNEAPOLIS | MINNEAPOLIS, MN T3 WEST MIDTOWN | ATLANTA, GA BUILDING FEATURES AND SPECIFICATIONS Industrial lofts were never built for modern workers. Until now. Developer: Hines Architect: DLR Group Property Management & Leasing: Hines & Stream Building: 275,000 SF Floorplate: 44,000 SF Private outdoor space on each floor 12’ finished floor-to-ceiling heights 255 parking spaces T3 GOOSE ISLAND | CHICAGO, IL Perfectly situated within minutes of Chicago’s hottest residential LOCATION neighborhoods, including Bucktown, Wicker Park, Fulton Market, West Town,River North, Lincoln Park, and the Gold Coast. Onni | 2,650 unit Uptake, Tempus, Marianos, Nando’s, FedEx multi-family development. Echo, Jump Trading Earls Kitchen, Kizuki Ramen Next College Student Athlete CTA Center Kendall College Whole Foods Off Color Brewing REI Dunkin Donuts Amazon Mars, Wrigley Sodikoff indoor/outdoor Wrigley Global MxD, Elite Staffing, hospitality experience Innovation Center Wrigley Transportation One, CB2 Boelter Morton -

Premier Goose Island Opportunity Uniquely Positioned to Serve the Creative Class

Premier Goose Island Opportunity Uniquely positioned to serve the creative class CHICAGO, IL 50,000 - 250,000 SF on 3.2 Acres PREMIER GOOSE ISLAND OPPORTUNITY Creative office and showroom space for Lease/Built To Suit CONTACT INFORMATION The sale of 1200 N. North Branch, Chicago, IL is being exclusively marketed by the Chicago office of Colliers International. Please contact the individuals below to answer any questions. MICHAEL L SENNER, SIOR Executive Vice President +1 847 698 8234 [email protected] VERNON F SCHULTZ, SIOR Executive Vice President +1 847 698 8233 [email protected] This document has been prepared by Colliers International for advertising and general information only. Colliers International makes no guarantees, representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the information including, but not limited to, warranties of content, accuracy and reliability. Any interested party should undertake their own inquiries as to the accuracy of the information. Colliers International excluded unequiv- ocally all inferred or implied terms, conditions and warranties arising out of this document and excludes all liability for loss and damages arising there from. This publication is the copyrighted property of Colliers International and/ or its licensor(s). © 2015. All rights reserved. INVESTMENT SUMMARY OFFERING SUMMARY On behalf of R2 Companies, the Chicago office of Colliers International is pleased to present 1200 N. North Branch located on “Goose Island” in Chicago, Illinois. The 3.2 acres (137,531 square feet) and 52,973 square feet BUCKTOWN LINCOLN PARK of improvements (expandable to ±90,000 SF) are currently available for lease. Additionally, ownership will consider a built to suit. -

Epared This Community Involvement Plan (CIP) for the Four Peoples Gas Cleanup Sites Located on the Near North Side, One of 77 Well-Defined Community Areas of Chicago

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 5 Community Involvement Plan Peoples Gas Plant Sites: Division Street Station Hawthorne Avenue Station North Station Willow Street Station City of Chicago, Cook County, Illinois August 2009 Introduction U.S. Environmental Protection Agency prepared this community involvement plan (CIP) for the four Peoples Gas cleanup sites located on the Near North Side, one of 77 well-defined community areas of Chicago. The sites are found near Goose Island, which is located in the North Branch of the Chicago River. This CIP provides background information on the sites, describes activities EPA will perform to keep the public and local officials informed about progress at the sites, and encourages community involvement during cleanup of the sites. This CIP also lists the concerns of nearby residents and local officials regarding the sites and ways for EPA to address those concerns. The information in this CIP is based primarily on discussions with residents and local officials that occurred April 1-2, 2009. Site background EPA has entered into an agreement with Peoples Gas Company to oversee the company’s investigation of 11 former manufactured gas plant (MGP) sites in Chicago. Peoples Gas will investigate the extent and nature of contamination at each site, and then evaluate potential cleanup options. In consultation with Illinois EPA, the City of Chicago and area residents, EPA will make the final cleanup determinations. All of the properties covered by the agreement are relatively close to the Chicago River, which was a transportation route when the MGPs operated. These facilities produced gas from coal from the mid-19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................ -

After the Towers: the Destruction of Public Housing and the Remaking

After the Towers: The Destruction of Public Housing and the Remaking of Chicago by Andrea Field A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved March 2017 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Philip Vandermeer, Chair Deirdre Pfeiffer Victoria Thompson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 ©2017 Andrea Field All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of Cabrini-Green through the lens of placemaking. Cabrini-Green was one of the nation's most notorious public housing developments, known for sensational murders of police officers and children, and broadcast to the nation as a place to be avoided. Understanding Cabrini-Green as a place also requires appreciation for how residents created and defended their community. These two visions—Cabrini-Green as a primary example of a failed public housing program and architecture and Cabrini-Green as a place people called home—clashed throughout the site's history, but came into focus with its planned demolition in the Chicago Housing Authority's Plan for Transformation. Demolition and reconstruction of Cabrini-Green was supposed to create a model for public housing renewal in Chicago. But residents feared that this was simply an effort to remove them from valuable land on Chicago's Near North Side and deprive them of new neighborhood improvements. The imminent destruction of the CHA’s high-rises uncovered desires to commemorate the public housing developments like Cabrini-Green and the people who lived there through a variety of public history and public art projects. This dissertation explores place from multiple perspectives including architecture, city planning, neighborhood development, and public and oral history. -

Signature of Author

PLANNING FOR COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE NEAR NORTH SIDE OF CHICAGO: A Study For The YMCA Robert E. Brooker Inter-Agency Center by Donna Margaret Ducharme B.A., Carleton College (1977) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May, 1982 (Donna M. Ducharme 1982 Signature of Author..........,...,........ .,. .,.,,... Department of Urban Studies and Planning, May, 1982 Certified by.. Thesis Supervisor Accepted by.......,...o...&. ,,...,,,..... ......... ,,..... .. Chairman, Departmental Comittee on Graduate Students MAACHuSr Nm OF T H (LOGY UQRARES PLANNING FOR COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE NEAR NORTH SIDE OF CHICAGO; A Study For The YMCA Robert E. Brooker Inter-Agency Center by Donna Margaret Ducharme Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in May, 1982 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of City Planning ABSTRACT This thesis is a study for the Robert E. Brooker Center of the YMCA of Metro- politan Chicago. It addresses the question, what are the important place re- lated characteristics and interactions that inform choices about how the YMCA should proceed in organizing for community economic development in the area. The place related analysis is used as a basis to explore the question, what is community economic development and what sorts of community economic de- velopment objectives and strategies should be employed to impact the situa- tion. In this case, the place is the Near North Side of Chicago, an inner city community that contains both the wealthiest and the poorest residents in the city. A substantial, but declining manufacturing base and a healthy non-manufacturing base exist in different parts of the area. -

Microsoft Photo Editor

GOOSE ISLAND OVERLOOK This property was once used as a coal storage yard and boat yard prior to its acquisition by the Site No 01 City of Chicago in 2003 thanks to a grant funded by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. The large crane and other structures on the prop- erty are in the process of being removed. The river bank will be graded and the concrete removed. The Chicago Park District will be the eventual owner of the property after the clean-up is completed. Designs are not completed, but improvement of natural habitat will be a strong component within the plan. There will also be a water access point for canoes and kayaks. The park will be used primarily for passive recreation. ARMITAGE C LY KENN B E O L U S RN EDY T O N NORTH DAMEN ASHLAND HALSTED DIVISION Chica go River CHICAGO M ILWA U K E GRAND E KINZIE 1200 NORTH / 1100 WEST OGDEN Goose Island Overlook O . 01 N ADDRESS 1200 N Elston Ave OWNER City of Chicago ACREAGE 1.65 HABITATS 1 Riparian/Water Edge Goose Island Overlook N BR DIRECTIONS Park at 1111 N. Elston; ANC the site is visible through EL S H the fence, or walk out TO CHICAGO onto the Division Street N bridge and view it from RIV the river side. ER Chicago Habitat Directory 2005 58 Page Page 58 100 Feet Riverdale Bend Woods goes for almost a mile The Major Taylor Trail goes through the western RIVERDALE BEND WOODS along the Little Calumet River, and in some places part of the site connecting the Forest Preserve is quite wide, making it a valuable green corridor. -

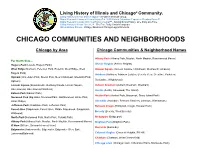

Chicago Communities and Neighborhoods

Living History of Illinois and Chicago® Community. Living History of Illinois and Chicago® - A Public Facebook Group. Digital Research Library of Illinois History® + 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition Reading Room™ Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ - Saving Illinois History, One Story at a Time. Living History of Illinois Gazette™ - The Free Daily Illinois Newspaper. Illinois History Store® - Vintage Illinois and Chicago Logo’d Products. CHICAGO COMMUNITIES AND NEIGHBORHOODS Chicago by Area Chicago Communities & Neighborhood Names Albany Park (Albany Park, Mayfair, North Mayfair, Ravenswood Manor) Far North Side--- (Archer Heights) Rogers Park (Loyola, Rogers Park)) Archer Heights West Ridge (Nortown, Peterson Park, Rosehill, West Ridge, West Armour Square (Armour Square, Chinatown, Wentworth Gardens) Rogers Park) Ashburn (Ashburn, Ashburn Estates, Beverly View, Crestline, Parkview, Uptown (Clarendon Park, Buena Park, New Chinatown, Sheridan Park, Scottsdale, Wrightwood) Uptown) Lincoln Square (Bowmanville, Budlong Woods, Lincoln Square, Auburn Gresham (Auburn Gresham, Gresham) Ravenswood, Ravenswood Gardens) Austin (Austin, Galewood, The Island) Edison Park (Edison Park) Avalon Park (Avalon Park, Marynook, Stony Island Park) Norwood Park (Big Oaks, Norwood Park, Old Norwood, Oriole Park, Union Ridge) Avondale (Avondale, Belmont Gardens, Jackowo, Wacławowo) Jefferson Park (Gladstone Park, Jefferson Park) Belmont Cragin (Brickyard, Cragin, Hanson Park) Forest Glen (Edgebrook, Forest Glen, Middle Edgebrook, Sauganash, -

Chicago River Trail Action Plan

CHICAGO RIVER TRAIL ACTION PLAN 1 The Vision We envision a seamless Chicago River Trail system that will provide a low-stress corridor for people walking, running and biking. The Chicago River Trail will be made up of a diverse array of elements, including riverside, floating and decked trails, on-street connections and robust wayfinding. Building the trail structure on or over the water is key to expediting trail construction since riverside land is currently unavailable in places. The Chicago River Trail will be accessed by a safe and comfortable network of streets designed to ensure people on foot, bike and New sections of a riverwalk may be added along the river, such as this transit have easy access to the river no matter their point of origin. stretch between Bubbly Creek and Ashland Ave. Rendering courtesy of Great Rivers Chicago. The Chicago River Trail will provide residents an opportunity to celebrate and embrace Chicago’s unique neighborhoods, The Opportunity its history and its diversity. Urban waterfronts provide cities with unique possibilities for recreation, open space and transportation. Many world class cities have invested in developing waterfront parks and trails in order to connect residents with the myriad quality of life benefits they can bring, such as improved health, cleaner environments and economic opportunity. While Chicago’s lakefront park and trail system is second to none, the Chicago River has not yet reached its full potential as a community recreation and active transportation asset. A continuous Chicago River Trail system would help transform a neglected waterway into vibrant open space and an active transportation corridor connecting Chicago’s diverse neighborhoods to the river and to each other.