Craig Mcgregor'^

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Reading

SECOND READING Parliamentary Government in Western Australia (Revised Internet Edition) Harry CJ Phillips Original Edition Copyright © 1991, Ministry of Education, Western Australia . Reproduction of this work in whole or part for educational purposes within an educational institution in Western Australia and on condition that it not be offered for sale, is permitted by the Ministry of Education. Designed and illustrated by Rod Lewis and computer typeset by West Ed Media, Ministry of Education. Printed by State Print, Department of State Services. ISBN 0 7309 4532 4 ISBN 0 7309 4127 2 (loose-leaf) Internet Edition First published 2003 by Parliament of Western Australia, Parliament House, Perth, Western Australia Revised Internet Edition © Western Australia, 2010 Reproduction of this work in whole or part for educational purposes within an educational institution in Western Australia and on condition that it not be offered for sale, is permitted by the Parliament of Western Australia. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface (i) Acknowledgements (ii) 1. Citizens of Western Australia: Government and Politics 1 Chapter 1 - Terms 7 2. Australia’s Federal System 8 Chapter 2 - Terms 21 3. Parliament’s History in Western Australia 22 Chapter 3 - Terms 32 4. The Western Australian Constitutional Framework 33 Chapter 4 - Terms 44 5. How a Law is Made in Western Australia 45 Chapter 5 - Terms 58 6. People in Western Australia’s Parliament 59 Chapter 6 - Terms 66 7. Parliament at Work 67 Chapter 7 - Terms 79 8. Parliament House 80 Chapter 8 - Terms 92 9. Elections and Referendums 93 Chapter 9 - Terms 109 10. Political Parties and Party Leaders 110 Chapter 10 - Terms 120 11. -

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

Lee Kuan Yew the Press Gallery�S Love Affair with Mr Keating Interviewed by Owen Harries Looks Like It�S Over

INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS LIMITED (Incorporated in the ACT) ISSN 1030 4177 IPA REVIEW Vol. 43 No. I June-August 1989 ki Productivity: the Prematurely r Counted Chicken John Brunner New figures show that plans for a national wage 2 IPA Indicators rise based on productivity gains are misplaced. In 30 years government expenditure per head in Australia has more than doubled. 13 Industrial Relations: the British Alternative 3 Editorials Joe Thompson The death throes of communism will be long and painful. Economic reform in Australia is moving The "British disease" has become a thing of the too slowly. Mr Keating on smaller government. past. Now Australia should take the cure. 8 - Press Index E Lee Kuan Yew The press gallerys love affair with Mr Keating Interviewed by Owen Harries looks like its over. Mr Macphee wins hearts, but Singapores experienced and astute PM on issues not where it counts. ranging from Gorbachev to regional trade. 11 Defending Australia 32 Myth and Reality in the Conservation Harry Gelber Debate The massacre in Beijing has burst the bubble of Ian Hore-Lacy illusion surrounding China. A cool assessment of the facts in an emotional debate. 16 Around the States Les McCaffrey 38 Big Governments Threat to the Rule If governments want investment they must stop of Law forever changing the rules. Denis White Youth Affairs How regulations can undermine the law. 25 Cliff Smith 48 Militarism and Ideology One hundred young Australians debate their Michael Walker countrys future. For Marxists in power the armed struggle continues. 26 Strange Times Ken Baker 50 Terms of Reference The Sex Pistols corrupted by capitalism; Billy John Nurick Bragg on being inspired by Leninism. -

Download Here

Heritage Newsletter of the Blue Mountains Association of Cultural Heritage Organisations Inc November-December 2015 ISSUE 41 ISSN 2203-4366 The Hydro Majestic Hotel The iconic hotel was created by Mark Foy the Sydney businessman, sportsman and playboy, in 1904. The initial complex comprised three earlier buildings: The single storey country retreat of WH Hargraves, son of Edward Hargraves of gold discovery fame. This home had been built in two stages, a Victorian style cottage, followed by a two storey extension which became the Delmonte Hallway. Hargraves land also included 9km of bush walking tracks, available to the public. Foy leased the property in 1902 and purchased it in 1903. The existing hotel called the Belgravia, opened in 1891 by Mr & Mrs Ellis. Cottage owned by local solicitor Alfred Tucker. In 1904 Mark Foy created his hydropathic establishment, opening the facility on 4th July to attract American visitors, advertising cures for nervous, alimentary, respiratory and circulatory ailments, but did not include sufferers of infectious diseases and mental illness. 1 HERITAGE November-December 2015 He believed that the land contained mineral springs, although this was probably in error, as Foy was importing mineral water from Germany. The town was then known as Medlow, and Foy petitioned the NSW Government to change the name to Medlow Bath. Belgravia Hargraves House Tucker cottage Hydro Majestic 1904 - Casino A striking prefabricated casino was brought in from Chicago, and erected between Hargravia and Belgravia with the picture gallery joining the buildings together. The dome was built to Foy’s specifications and dismantled for shipping. Guests enjoyed the magnificent view over the Megalong Valley and a resident Swiss doctor, George Baur, attended to their ailments. -

![Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL - Wednesday, 28 November 2001] P5953b-5960A Hon Peter Foss; Hon Frank Hough](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1316/extract-from-hansard-council-wednesday-28-november-2001-p5953b-5960a-hon-peter-foss-hon-frank-hough-491316.webp)

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL - Wednesday, 28 November 2001] P5953b-5960A Hon Peter Foss; Hon Frank Hough

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL - Wednesday, 28 November 2001] p5953b-5960a Hon Peter Foss; Hon Frank Hough ELECTORAL AMENDMENT BILL 2001 Second Reading Resumed from 26 September. HON PETER FOSS (East Metropolitan) [4.10 pm]: It is fortuitous that you read that statement and the letter from the Clerk of the House, Mr President, because I intended to commence my speech by raising an entirely different reason that the Bill requires an absolute majority - one that was not canvassed by the Standing Committee on Legislation. It is important that you are here because I believe that you have no alternative but to rule at the second reading stage. As you are aware, Mr President, two items are on the Notice Paper: the Electoral Amendment Bill 2001 and the Electoral Distribution Repeal Bill 2001. It has sometimes struck people as curious that two Bills are on the Notice Paper. We suspected that that was to circumvent the requirements of the Electoral Distribution Act. I suggest that the introduction of these two Bills has become a complete mess-up, but a stronger phrase than mess-up would be appropriate and I will explain why. They are two separate Bills. There is nothing to say that either of them will be passed into law. You must deal only with the Electoral Amendment Bill 2001, Mr President, not the Electoral Distribution Repeal Bill. The amending Bill makes no reference whatsoever to the Electoral Distribution Act. It happens to deal with exactly the same measures as the other Bill; therefore, this Bill operates one way or another to affect the Electoral Distribution Act. -

Fourteen Studies in Qorporate Crime Or Corporate Harm. STAINS on a WHITE COLLAR Mmmmik Ikim

Chris Masters Fourteen studies in qorporate crime or corporate harm. STAINS ON A WHITE COLLAR mmmmik IKiM [Fmj^iBBou UiB^BB^ to Edited by Peter Grabosky and Adam Sutton Foreword by Chris Masters THE FEDERATION PRESS Published in Sydney by The Federation Press 101A Johnston Street Annandale. NSW. 2038 In association with Bow Press Pty Ltd 208 Victoria Road Drummoyne. NSW. 2047 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Stains on a white collar: fourteen studies in corporate crime or corporate harm. Bibliography. ISBN 1 86287 009 8. 1. Commercial crimes — Australia — Case studies. 2. Corporations — Australia — Corrupt practices — Case studies. 3. White collar crimes — Australia — Case studies. I. Grabosky, Peter N. (Peter Nils), 1945- . II. Sutton, Adam Crosbie. 364.1'68'0994 Copyright ® this collection The Australian Institute of Criminology This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Cover designed by Hand Graphics Text designed by Steven Dunbar Typeset in 10 pt Century Old Style by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough Printed in Australia by Griffin Press Production by Vantage Graphics, Sydney CONTENTS FOREWORD ix CHRIS MASTERS INTRODUCTION xi 1 THE BOTTOM OF THE HARBOUR TAX EVASION -

Anarchism in Australia

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Australia Bob James Bob James Anarchism in Australia 2009 James, Bob. “Anarchism, Australia.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 105–108. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Gale eBooks (accessed June 22, 2021). usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 James, B. (Ed.) (1983) What is Communism? And Other Essays by JA Andrews. Prahran, Victoria: Libertarian Resources/ Backyard Press. James, B. (Ed.) (1986) Anarchism in Australia – An Anthology. Prepared for the Australian Anarchist Centennial Celebra- tion, Melbourne, May 1–4, in a limited edition. Melbourne: Bob James. James, B. (1986) Anarchism and State Violence in Sydney and Melbourne, 1886–1896. Melbourne: Bob James. Lane, E. (Jack Cade) (1939) Dawn to Dusk. N. P. William Brooks. Lane, W. (J. Miller) (1891/1980) Working Mans’Paradise. Syd- ney: Sydney University Press. 11 Legal Service and the Free Store movement; Digger, Living Day- lights, and Nation Review were important magazines to emerge from the ferment. With the major events of the 1960s and 1970s so heavily in- fluenced by overseas anarchists, local libertarians, in addition Contents to those mentioned, were able to generate sufficient strength “down under” to again attempt broad-scale, formal organiza- tion. In particular, Andrew Giles-Peters, an academic at La References And Suggested Readings . 10 Trobe University (Melbourne) fought to have local anarchists come to serious grips with Bakunin and Marxist politics within a Federation of Australian Anarchists format which produced a series of documents. Annual conferences that he, Brian Laver, Drew Hutton, and others organized in the early 1970s were sometimes disrupted by Spontaneists, including Peter McGre- gor, who went on to become a one-man team stirring many national and international issues. -

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

Masterplan Stage 04 - Masterplan Report

PAUL KEATING PARK MASTERPLAN STAGE 04 - MASTERPLAN REPORT PAUL KEATING PARK MASTERPLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the next 20 years, the Bankstown CBD will see substantial growth The Appian Way offers a major pedestrian entrance into the site from and increased demand on its parks, streets and cultural facilities due to Bankstown Metro Station, providing access to surrounding buildings greater amounts of jobs, students and residents. The Paul Keating Park and programs, and integrating environmental functionality. Adjacent to Masterplan presents the opportunity to respond to this future trajectory, this, the Play Space offers further amenity and shade, with a custom, focusing on the Civic Precinct, the centrepiece of Bankstown CBD, inclusive and varied playground and spaces for parents congregate. The to revitalise open space offerings whilst also addressing the current Green Incline, by contrast, offers access to sunshine and a large open challenges of the site. space for leisure, resolving connectivity between upper and lower levels of the site, and providing the opportunity for an integrated community building below. The masterplan and design outcomes presented within this report are based on a detailed understanding of these challenges, along with the current and future contexts of the site. These studies are incorporated A redesigned entryway to BLaKC, incorporating an outdoor dining within the initial chapters of the report through context mappings, site terrace and an opened-up façade, activates the existing building from considerations diagrams and design principles that were used as a Chapel St and allows a transition of programs between interior and framework for producing the masterplan. Furthermore, community exterior. -

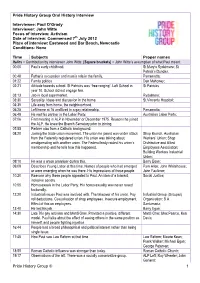

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

The Railway Technical Society of Australasia – the First Ten Years

The Railway Technical Society of Australasia The First Ten Years Philip Laird ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA RTSA The Railway Technical Society of Australasia The First Ten Years Philip Laird What may have been. An image from the 1990s of a future Speedrail Sydney - Canberra train at Sydney’s Central Station. Photo: Railway Digest/ARHSnsw. Three Vlocity trains standing at Southern Cross Station. These trains coupled with track upgrades as part of Victoria’s Regional Fast Rail program have seen a 30 per cent increase in patronage in their first full year of operation. Photo: Scott Martin 2008 Contents Introduction 4 RTSA Executive Chairman Ravi Ravitharan Acknowledgements Foreword 5 Hon Tim Fischer AC Section 1 Railways in Australasia 6 Section 2 The National Committee on Railway Engineering 11 Section 3 The Railway Technical Society of Australasia 17 3.1 The formation and early years 17 The Railway Technical Society of Australasia 3.2 Into the 21st century (2000 - 2004) 22 PO Box 6238, Kingston ACT 2604 3.3 Recent developments (2004 - 2008) 27 ABN 380 582 55 778 Section 4 Engineering and rail sector growth 34 4.1 The iron ore railways 34 © Copyright Philip Laird 4.2 Rail electrification in Queensland 36 and the Railway Technical Society of Australasia 2008 4.3 Queensland ‘s Mainline Upgrade 38 4.4 An East - West success story 40 Design and prepress by Ruby Graphics 4.5 The Australian Rail Track Corporation 42 Printed and bound by BPA Print Group 4.6 Perth’s urban rail renaissance 44 PO Box 110, Burwood VIC 3125 4.7 Rail in other capital cities 46 4.6 Trams and light rail 48 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 4.9 New railways in Australia 50 4.10 New Zealand railways 52 Title: The Railway Technical Society of Australasia : the first ten years / Philip Laird. -

George Bush Presidential Library Records on Australia

George Bush Presidential Library 1000 George Bush Drive West College Station, TX 77845 phone: (979) 691-4041 fax: (979) 691-4030 http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu [email protected] Inventory for FOIA Request 2003-0345-F Records on Australia Extent 849 folders Access Collection is open to all researchers. Access to Bush Presidential Records, Bush Vice Presidential Records, and Quayle Vice Presidential Records is governed by the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)(5 USC 552 as amended) and the Presidential Records Act (PRA)(44 USC 22) and therefore records may be restricted in whole or in part in accordance with legal exemptions. Copyright Documents in this collection that were prepared by officials of the United States government as part of their official duties are in the public domain. Researchers are advised to consult the copyright law of the United States (Title 17, USC) which governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Provenance Official records of George Bush's presidency and vice presidency are housed at the George Bush Presidential Library and administered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). Processed By Staff Archivists, January 2009. Previously restricted materials are added as they are released. Scope and Content [Provides information about the nature of the materials and activities reflected in the unit being described to enable users to judge its potential relevance. Include the functions, activities, transactions,