Gough Whitlam and the ‘Grounds’ for a University of Western Sydney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooma Monaro Final Report 2015

Cooma-Monaro Shire Final Report 2015 Date: 22 October 2015 Cooma-Monaro LGA Final Report 2015 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LGA OVERVIEW Cooma-Monaro Local Government Area The Cooma-Monaro Shire Council area is located in the south east region of NSW. The Shire comprises a land area of approximately 5229 square kilometres comprising undulating to hilly rural grazing land, timbered lifestyle areas and retreat bushland. The Local Government Area (LGA) is adjoined by four other LGAs – Palerang to the north, Tumut and Snowy River to the west, Bombala to the south and Bega Valley to the east. The main economic activities in the Shire include sheep and cattle grazing plus the “provision” of hobby farms / rural home sites in the Cooma area for the Cooma market, in the Michelago area (ie the northern part of the Shire) for the Canberra market and at various other locations including along the Murrumbidgee River and at the southeast periphery near Nimmitabel. These rural/ residential blocks and bush retreats cater for a number of sub markets and demand tends to ebb and flow. Number of properties valued this year and the total land value in dollars The Cooma-Monaro LGA comprises Residential, Rural, Commercial, Industrial, Infrastructure/Special Purposes, Environmental and Public Recreation zones. 5,388 properties were valued at the Base Date of 1 July 2015, and valuations are reflective of the property market at that time. Previous Notices of Valuation issued to owners for the Base Date of 1 July 2014. The Snowy River LGA property market generally has remained static across all sectors with various minor fluctuations. -

When Australia Said NO! Fifteen Years Ago, the Australian People Turned Down the Menzies Govt's Bid to Shackle Democracy

„ By ERNIE CAMPBELL When Australia said NO! Fifteen years ago, the Australian people turned down the Menzies Govt's bid to shackle democracy. gE PT E M B E R . 22 is the 15th Anniversary of the defeat of the Menzies Government’s attempt, by referendum, to obtain power to suppress the Communist Party. Suppression of communism is a long-standing plank in the platform of the Liberal Party. The election of the Menzies Government in December 1949 coincided with America’s stepping-up of the “Cold War”. the Communist Party an unlawful association, to dissolve it, Chairmanship of Senator Joseph McCarthy, was engaged in an orgy of red-baiting, blackmail and intimidation. This was the situation when Menzies, soon after taking office, visited the United States to negotiate a big dollar loan. On his return from America, Menzies dramatically proclaimed that Australia had to prepare for war “within three years”. T o forestall resistance to the burdens and dangers involved in this, and behead the people’s movement of militant leadership, Menzies, in April 1950, introduced a Communist Party Dis solution Bill in the Federal Parliament. T h e Bill commenced with a series o f recitals accusing the Communist Party of advocating seizure of power by a minority through violence, intimidation and fraudulent practices, of being engaged in espionage activities, of promoting strikes for pur poses of sabotage and the like. Had there been one atom of truth in these charges, the Government possessed ample powers under the Commonwealth Crimes Act to launch an action against the Communist Party. -

The Removal of Whitlam

MAKING A DEMOCRACY to run things, any member could turn up to its meetings to listen and speak. Of course all members cannot participate equally in an org- anisation, and organisations do need leaders. The hopes of these reformers could not be realised. But from these times survives the idea that any governing body should consult with the people affected by its decisions. Local councils and governments do this regularly—and not just because they think it right. If they don’t consult, they may find a demonstration with banners and TV cameras outside their doors. The opponents of democracy used to say that interests had to be represented in government, not mere numbers of people. Democrats opposed this view, but modern democracies have to some extent returned to it. When making decisions, governments consult all those who have an interest in the matter—the stake- holders, as they are called. The danger in this approach is that the general interest of the citizens might be ignored. The removal of Whitlam The Labor Party captured the mood of the 1960s in its election campaign of 1972, with its slogan ‘It’s Time’. The Liberals had been in power for 23 years, and Gough Whitlam said it was time for a change, time for a fresh beginning, time to do things differently. Whitlam’s government was in tune with the times because it was committed to protecting human rights, to setting up an ombuds- man and to running an open government where there would be freedom of information. But in one thing Whitlam was old- fashioned: he believed in the original Labor idea of democracy. -

Australian Wine Discovered

CHARDONNAY AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED Australia’s unique climate and landscape have fostered a fiercely independent wine scene, home to a vibrant community of growers, winemakers, viticulturists, and vignerons. With more than 100 grape varieties grown across 65 distinct wine regions, we have the freedom to make exceptional wine, and to do it our own way. We’re not beholden by tradition, but continue to push the boundaries in the pursuit of the most diverse, thrilling wines in the world. That’s just our way. AUSTRALIAN CHARDONNAY: T H E EVOLUTION Australian Chardonnay has enjoyed the industry’s highs OF A CLASSIC and weathered its lows with resilience, and it continues to hold a special place for Australian wine lovers. Its Australian journey is a roller‑coaster ride of dramatic proportions. TO DAY - The history of WE’LL Australian Chardonnay - How it’s grown - How it’s made - The different styles - Where it’s grown - Characteristics and flavour profiles COVER… - Chardonnay by numbers THE HISTORY 1908 1969 Tyrrell’s HVD vineyard is Craigmoor’s cuttings OF AUSTRALIAN planted in Hunter Valley, identified as one of now one of the oldest the best Chardonnay CHARDONNAY Chardonnay vineyards clones with European in the world. provenance in Australia. 1820s –1930s 1918 Chardonnay is one of the Chardonnay cuttings from original varieties brought Kaluna Vineyard in Sydney’s to Australia and thrives in Fairfield are given to a Roth the warm, dry climate. family member, who plants them at Craigmoor Vineyards in Mudgee. EARLY 1970s 1980s Consumer preferences A new style of shift to table wines, with 1979 Chardonnay enters the new styles produced, Winemaker Brian Croser wine market. -

Whitlam As Internationalist: a Centenary Reflection

WHITLAM AS INTERNATIONALIST: A CENTENARY REFLECTION T HE HON MICHAEL KIRBY AC CMG* Edward Gough Whitlam, the 21st Prime Minister of Australia, was born in July 1916. This year is the centenary of his birth. It follows closely on his death in October 2014 when his achievements, including in the law, were widely debated. In this article, the author reviews Whitlam’s particular interest in international law and relations. It outlines the many treaties that were ratified by the Whitlam government, following a long period of comparative disengagement by Australia from international treaty law. The range, variety and significance of the treaties are noted as is Whitlam’s attraction to treaties as a potential source of constitutional power for the enactment of federal laws by the Australian Parliament. This article also reviews Whitlam’s role in the conduct of international relations with Australia’s neighbours, notably the People’s Republic of China, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Indochina. The reconfiguration of geopolitical arrangements is noted as is the close engagement with the United Nations, its agencies and multilateralism. Whilst mistakes by Whitlam and his government are acknowledged, his strong emphasis on international law, and treaty law in particular, was timely. It became a signature theme of his government and life. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 852 II Australia’s Ratification of International Treaties ................................................. -

Corporatised Universities: an Educational and Cultural Disaster

John Biggs and Richard Davis (eds), The Subversion of Australian Universities (Wollongong: Fund for Intellectual Dissent, 2002). Chapter 12 Corporatised universities: an educational and cultural disaster John Biggs Where from here? Australian universities have been heavily criticised in these pages, and some specific examples of where things have gone wrong have been reported in detail. Not everyone sees these events negatively, how- ever. Professor Don Aitken, until recently Vice-Chancellor of the University of Canberra, said: I remain optimistic about the future of higher education in Australia. … To regard what is happening to universities in Australia as simply the work of misguided politicians or managers is abysmally paro- chial.1 Are the authors in this book concentrating too much on the damage that has been done? Is a greater good emerging that we have missed so far? As was pointed out in the Preface, globalisation is upon us; it is less than helpful to command, Canute-like, the tide to retreat. Rather the wise thing would be to acknowledge what we cannot change, and focus on what we can change. At the least, we need a resolution that is more academically acceptable than the one we have. The Vice-Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh, Professor Stuart Sutherland, in commenting on parallel changes in Britain, put it this way: 185 The subversion of Australian universities The most critical task for universities is to recreate a sense of our own worth by refashioning our understanding of our identity — our under- standing of what the word “university” means. …The trouble is that in the process of expansion and diversification, the place that universities had at the table has not simply been redefined; it has been lost.2 Australian universities too have lost their place at the table. -

The Secret Life of Elsie Curtin

Curtin University The secret life of Elsie Curtin Public Lecture presented by JCPML Visiting Scholar Associate Professor Bobbie Oliver on 17 October 2012. Vice Chancellor, distinguished guests, members of the Curtin family, colleagues, friends. It is a great honour to give the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library’s lecture as their 2012 Visiting Scholar. I thank Lesley Wallace, Deanne Barrett and all the staff of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, firstly for their invitation to me last year to be the 2012 Visiting Scholar, and for their willing and courteous assistance throughout this year as I researched Elsie Curtin’s life. You will soon be able to see the full results on the web site. I dedicate this lecture to the late Professor Tom Stannage, a fine historian, who sadly and most unexpectedly passed away on 4 October. Many of you knew Tom as Executive Dean of Humanities from 1999 to 2005, but some years prior to that, he was my colleague, mentor, friend and Ph.D. supervisor in the History Department at UWA. Working with Tom inspired an enthusiasm for Australian history that I had not previously known, and through him, I discovered John Curtin – and then Elsie Curtin, whose story is the subject of my lecture today. Elsie Needham was born at Ballarat, Victoria, on 4 October 1890 – the third child of Abraham Needham, a sign writer and painter, and his wife, Annie. She had two older brothers, William and Leslie. From 1898 until 1908, Elsie lived with her family in Cape Town, South Africa, where her father had established the signwriting firm of Needham and Bennett. -

Whitlam and China

WHITLAM AND CHINA Prime Ministers Series November 2014 FRONT COVER IMAGE: Gough and Margaret Whitlam visit the Temple of Heaven in Beijing November, 1973. © File photo/NLA/Xinhua CONTENTS Introduction 4 Whitlam and China: 6 Transcript of Panel Discussion, Sydney, November 6 2014 A Note from Graham Freudenberg - Terrill and Taiwan (November 9 2014) 35 Whitlam Timeline 38 Further Reading 40 The Panellists 42 Published by Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) University of Technology, Sydney PO Box 123 Broadway NSW 2007 Australia t: +61 2 9514 8593 f: +61 2 9514 2189 e: [email protected] w: www.acri.uts.edu.au © Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) 2015 ISBN 978-0-9942825-0-7 The publication is copyright. Other than for uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without attribution. INTRODUCTION ACRI is proud to have hosted this discussion of Gough Whitlam’s 1971 visit which opened up the contemporary relationship between Australia and China. It is sad that we weren’t able to interview Gough Whitlam about China in the way we intend to interview other Australian Prime Ministers. But we are honoured to add this transcript to the many tributes to Australia’s 21st Prime Minister. In our panel conversation, a long-term Whitlam advisor and friend, 81 year old Graham Freudenberg, recreated the tension around the visit. Mr Whitlam was Opposition Leader; he was taking a political risk in going to ‘Red China’. Mr Freudenberg, a master of story- telling, captured the sense of excitement felt by the Whitlam party encamped at the Peking Hotel. -

Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915

5 Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915. Andrew Fisher became the 5th prime minister when the Liberal- Labor coalition government headed by Alfred Deakin collapsed due to loss of parliamentary Labor support. Fisher’s first period as prime minister ended when the new Fusion Party of Deakin and Joseph Cook defeated the government in parliament. His second term resulted from an overwhelming Labor victory at elections in 1910. However, Labor lost power by one seat at the 1913 elections. Fisher was prime minister again in 1914, as a result of a double-dissolution election. Fisher resigned from office in October 1915, his health affected by the pressures of political life. Member of the Australian Labor Party c1901-28. Member of the House of Representatives for the seat of Wide Bay (Queensland) 1901-15; Minister for Trade and Customs 1904; Treasurer 1908-09, 1910-13, 1914-15. Main achievements (1904-1915) Under his prime ministership, the Commonwealth Government issued its first currency which replaced bank and State currency as the only legal tender. Also, the Commonwealth Bank was established. Strengthened the Conciliation and Arbitration Act. Introduced a progressive land tax on unimproved properties. Construction began on the trans-Australian railway, linking Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. Established the Australian Capital Territory and brought the Northern Territory under Commonwealth control. Established the Royal Australian Navy. Improved access to invalid and aged pensions and brought in maternity allowances. Introduced workers’ compensation for federal public servants. -

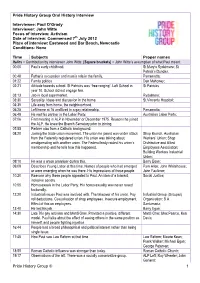

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

The Life and Times of the Remarkable Alf Pollard

1 FROM FARMBOY TO SUPERSTAR: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REMARKABLE ALF POLLARD John S. Croucher B.A. (Hons) (Macq) MSc PhD (Minn) PhD (Macq) PhD (Hon) (DWU) FRSA FAustMS A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology, Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August 2014 2 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 12 August 2014 3 INTRODUCTION Alf Pollard’s contribution to the business history of Australia is as yet unwritten—both as a biography of the man himself, but also his singular, albeit often quiet, achievements. He helped to shape the business world in which he operated and, in parallel, made outstanding contributions to Australian society. Cultural deprivation theory tells us that people who are working class have themselves to blame for the failure of their children in education1 and Alf was certainly from a low socio-economic, indeed extremely poor, family. He fitted such a child to the letter, although he later turned out to be an outstanding counter-example despite having no ‘built-in’ advantage as he not been socialised in a dominant wealthy culture. -

Stephen Wilks Review of John Murphy, Evatt: a Life

Stephen Wilks review of John Murphy, Evatt: A Life (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2016), 464 pp., HB $49.99, ISBN 9781742234465 When Herbert Vere Evatt died in November 1965 he was buried at Woden cemetery in Canberra’s south. His grave proclaims him as ‘President of the United Nations’ and reinforces the point by bearing the United Nations (UN) emblem. Misleading as this is—as president of the UN General Assembly rather than secretary-general, Evatt was more presiding officer than chief executive—it broadcasts his proud internationalism. The headstone inscription is equally bold—‘Son of Australia’. The Evatt memorial in St John’s Anglican Church in inner Canberra is more subtle. This depicts a pelican drawing its own blood to feed its young, a classical symbol of self-sacrifice and devotion. These idealistic, almost sentimental, commemorations clash with the dominant image of Evatt as a political wrecker. This casts him as the woefully narcissistic leader of the federal parliamentary Labor Party who provoked the great split of 1954, when the party’s predominantly Catholic anti-communist right exited to form the Democratic Labor Party and help keep Labor out of office for the next 18 years. This spectre looms over Evatt’s independent Australian foreign policy and championing of civil liberties during the Cold War. John Murphy’s Evatt: A Life is the fourth full biography of the man, not to mention several more focused studies. This is better than most Australian prime ministers have managed. Evatt invites investigation as a coruscating intelligence with a clarion world view. His foremost achievements were in foreign affairs, a field attractive to Australian historians.