Projecting Into the World of Dungeons and Dragons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

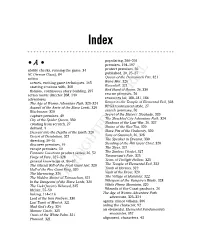

40_783307 bindex.qxp 3/16/06 8:51 PM Page 371 Index populating, 200–201 • A • premises, 194–197 ability checks, running the game, 34 protect premises, 50 AC (Armor Class), 84 published, 20, 25–27 action Queen of the Demonweb Pits, 321 scenes, exciting game techniques, 165 Rana Mor, 326 starting sessions with, 368 Ravenloft, 321 themes, continuous story building, 297 Red Hand of Doom, 26, 330 action movie director DM, 140 rescue premises, 50 adventures resources for, 180–181, 184 The Age of Worms Adventure Path, 323–324 Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil, 328 Assault of the Aerie of the Slave Lords, 320 RPGA tournament-style, 27 Blackrazor, 320 search premises, 50 capture premises, 49 Secret of the Slavers’ Stockade, 320 City of the Spider Queen, 330 The Shackled City Adventure Path, 324 creating from scratch, 27 Shadows of the Last War, 26, 327 defined, 4 Shrine of the Kuo-Toa, 320 Descent into the Depths of the Earth, 320 Slave Pits of the Undercity, 320 Desert of Desolation, 321 Sons of Gruumsh, 26, 328 directing, 50–51 The Speaker in Dreams, 330 discover premises, 49 Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, 320 escape premises, 50 The Styes, 324 Fantastic Locations product series, 26, 52 The Sunless Citadel, 327 Forge of Fury, 327–328 Tammeraut’s Fate, 325 general knowledge of, 86–87 Tears of Twilight Hollow, 325 The Glacial Rift of the Frost Giant Jarl, 320 The Temple of Elemental Evil, 322 Hall of the Fire Giant King, 320 Tomb of Horrors, 319 The Harrowing, 326 Vault of the Drow, 320 The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan, 321 The Village of -

HYPERCONSCIOUS a Psionics Adventure-Sourcebook for 7Th-Level Characters

® HYPERCONSCIOUS A psionics adventure-sourcebook for 7th-level characters By Bruce R. Cordell Uses the Third Edition rules from the v. 3.5 revision. Additional Credits Editing: Miranda Horner Cover Illustration: Kieran Yanner Interior Illustrations: Kev Crossley Cartography: Todd Gamble Production: Sue Weinlein Cook Creative Direction: Monte Cook Proofreading: Mike Johnstone Cover and Interior Page Design: Peter Whitley Playtesters: Voin Despotovic, Prince Elcock (lead), Ashwyn Rajagopalan ... and Tom Sample file For supplemental material, visit Monte Cook’s Website: <www.montecook.com> Malhavoc isa registered trademark and Eldritch Might is a trademark owned by Monte J. Cook. Sword & Sorcery and the Sword & Sorcery logo are trademarks of White Wolf Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. Artwork ©2004 Monte J. Cook. All other content is ©2004 Bruce R. Cordell. All rights reserved. The mention of or reference to any company or product in these pages is not a challenge to the trademark or copyright concerned. This edition of Hyperconscious is produced under version 1.0a and/or draft versions of the Open Game License and the System Reference Document by permission of Wizards of the Coast. Designation of Product Identity: The following items are hereby designated as Product Identity in accordance with Section 1(e) of the Open Game License, version 1.0a: Any and all Malhavoc Press logos and identifying marks and trade dress, such as all Malhavoc Press product and product line names including but not limited to The Book of Eldritch Might, Mindscapes, -

Liste De Modules *D&D

Liste de modules *D&D Liste de modules *D&D La dernière version est disponible sur le site D&D Collection (http://dndcollection.free.fr) Cette liste a été générée le 13/01/2004 Ce document a été créé à l'aide de FPDF Ecrivez à : [email protected] pour tout renseignement ou remarque Page 1 WIZARDS OF THE COAST, D&D, AD&D and all the campaign settings for *D&D are registered trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. This site (http://dndcollection.free.fr) is not affiliated with Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Liste de modules *D&D Allemand Page 2 WIZARDS OF THE COAST, D&D, AD&D and all the campaign settings for *D&D are registered trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. This site (http://dndcollection.free.fr) is not affiliated with Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Liste de modules *D&D AD&D 1ere Edition Dragonlance N° TSR Code Titre Module PDF Copie DL2 Drachen der Flammen DL1 Drachen der Verzweiflung DL5 Drachengeheimnisses Forgotten Realms N° TSR Code Titre Module PDF Copie I3-5 Wüste der Verdammnis Greyhawk N° TSR Code Titre Module PDF Copie 8609/9 L2 Auf der Spur des Attentäters 8608/0 L1 Begegnung auf dem Knochenhügel Monstrous Arcana N° TSR Code Titre Module PDF Copie 8301 Die Teufel der See Non classés N° TSR Code Titre Module PDF Copie 8650/0 N1 Gegen den Kult des Reptilien-Gottes Règles N° TSR Code Titre Module PDF Copie 8537/6 Monster Handbuch I 8538/5 Monster Handbuch II Mythen & Legenden 8136/1 Spieler Handbuch Page 3 WIZARDS OF THE COAST, D&D, AD&D and all the campaign settings for *D&D are registered trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. -

Aboleth Mage

Tuesday, 15 November 2016 Monster: Aboleth Mage Monster: Aboleth Mage For completeness' sake let's convert the aboleth mage, presented in Monster Manual. The aboleths are psionic creatures, but Monster Manual was released before Expanded Psionics Handbook, and I think this is why there was an "improved" monster included. This monster is based on the aboleth racial template from this post and uses Sorcery for its magical abilities. If I recall correctly, Lords of Madness mentions the aboleths use their special glyph magic, which I probably will try to represent later as an alphabet for Symbol magic. Typical Stats – Aboleth Mage ST: 36 (KYOS: 30) HP: 41 (KYOS: 37) Speed: 6.5 DX: 11 Will: 15 Move: 2 ground, 6 water IQ: 15 Per: 15 HT: 15 FP: 20 SM: +3 Dodge: 9 Parry: N/A DR: 3 (7 with Armor 2) Bite (11): 2d-2 cutting (KYOS: 3d-3 cutting). Reach C. Tentacle (11): 4d-2 crushing (KYOS: 5d+1 crushing) + follow-up 1d corrosion (10 1-minute cycles, HT-3 resist). Reach C. 1-3. Being moistened with cool, fresh water negates cycle damage. Using the follow-up damage costs 1 FP. Mucus Cloud (HT): Any creature that makes skin-to-skin contact with the aboleth must make a successful HT roll or lose the ability to breathe air and gain that ability to breathe water for a number of minutes equal to the margin of failure. Using this ability costs 1 FP. Wall of Ectoplasm (7): The aboleth can create a wall of ectoplasm of any shape it chooses in any place within 100 yards. -

The Sunless Citadel

The Sunless Citadel All things roll here: horrors of midnights, 2. Kobold Den. The characters’ foray into the citadel be- Campaigns of a lost year, gins with an incursion into the most accessible areas Dungeons disturbed, and groves of lights; of the fortress, where a tribe of kobolds has taken up Echoing on these shores, still clear, residence. The characters can avoid strife with the ko- bolds by agreeing to retrieve a lost pet for the kobold Dead ecstasies of questing knights— leader, and they might be able to persuade the kobolds Yet how the wind revives us here! to join their side. Arthur Rimbaud 3. Goblin Lair. The goblins that live deeper inside the — citadel consider themselves the owners of the place. They defend themselves aggressively against intru- his adventure concerns a once-proud sion, making it difficult to avoid combat with them. fortress that fell into the earth in an age 4. Hidden Grove. Eventually, the characters discover long past. Now known as the Sunless Cita- the lower level of the citadel and the Twilight Grove del, its echoing, broken halls house malign that lies within. There, they learn the truth about the creatures. Evil has taken root at the cita- enchanted fruit, and they must confront Belak the Out- del’s core, which is deep within a subter- cast and the Gulthias Tree. ranean garden of blighted foliage. Here a terrible tree and its dark shepherd plot in darkness. Running the Adventure The tree, called the Gulthias Tree, is shepherded by a twisted druid, Belak the Outcast. -

Baldur's Gate

Content Catalogue Version 9.01 Baldur’s Gate Descent into Avernus Credits D&D Organized Play: Christopher Lindsay D&D Adventurers League Administrators: Lysa Penrose, Amy Lynn Dzura, Claire Hoffman Greg Marks, Alan Patrick, Sam Simpson, Travis Woodall Effective Date 17 September 2019 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. D&D Adventurers League Catalogue IT WAS OGHMA, THE GOD OF KNOWLEDGE. Although I can’t really say that I met him, I suppose, as he was drunk and fast asleep in Cousin Roffler’s back lawn – or perhaps I should say ON Cousin Roffler’s back lawn. He was a giant of an avatar, sprawled out and snoring. I wonder how you get a god drunk? —Jan, a thief, to Minsc, a barbarian What is This? The Dungeons and Dragons Adventurers League has been around for a few years now, and a lot of content has been created during that time. -

The Sunless Citadel Combat Reference Document

The Sunless Citadel Combat Reference Document Monster Statistics and Reinforcement Information Introduction: This reference document was created for DMs planning to run The Sunless Citadel from Tales from the Yawning Portal. The material contained herein has three purposes: (1) to speed combat by eliminating the need to flip back and forth between pages within the same book, (2) to organize the information about the reinforcement movements of creatures within the Sunless Citadel, and (3) to apply monster variants and adjustments to save you the time of having to do this yourself. The game is better when combat is organized, exciting, and quick. More dice rolling, less page flipping! This reference assumes you have a Monster Manual (MM) and Tales from the Yawning Portal (TYP). by Aaron Harrell DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are Sampleproperty of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use fileof the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2017 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. -

Baldur's Gate

Content Catalogue Version 9.02 Baldur’s Gate Descent into Avernus Credits D&D Organized Play: Christopher Lindsay D&D Adventurers League Administrators: LaTia Bryant, Ma’at Crook, Will Doyle, Amy Lynn Dzura, Claire Hoffman, Greg Marks, Shawn Merwin, Alan Patrick, Travis Woodall Effective Date 17 September 2019 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. D&D Adventurers League Catalogue IT WAS OGHMA, THE GOD OF KNOWLEDGE. Although I can’t really say that I met him, I suppose, as he was drunk and fast asleep in Cousin Roffler’s back lawn – or perhaps I should say ON Cousin Roffler’s back lawn. He was a giant of an avatar, sprawled out and snoring. I wonder how you get a god drunk? —Jan, a thief, to Minsc, a barbarian What is This? The Dungeons and Dragons Adventurers League has been around for a few years now, and a lot of content has been created during that time. -

Adventurers League Content Catalog

Adventurers League Content Catalog D&D AL Admins … and you! Version: 7.01, September 2017 Next update: February 2018 Maintenance: [email protected] Organized Play: Chris Lindsay D&D Adventurers League Wizards Team: Adam Lee, Chris Lindsay, Mike Mearls, Matt Sernett D&D Adventurers League Administrators: Robert Adducci, Bill Benham, Travis Woodall, Claire Hoffman, Greg Marks, Alan Patrick, Sam Simpson Art: all art used with permission of Wizards of the Coast DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2016 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Not for resale. Permission granted to print or photocopy this document for personal use only. D&D Adventurers League Content Catalog 1 D&D Adventurers League Catalogue IT WAS OGHMA, THE GOD OF KNOWLEDGE. Although I can’t really say that I met him, I suppose, as he was drunk and fast asleep in Cousin Roffler’s back lawn – or perhaps I should say ON Cousin Roffler’s back lawn. -

Collectors Checklist by Richard © 2001, Version 2.7

Dungeons&Dragons Collectors Checklist by Richard © 2001, version 2.7 Well met and welcome to the Collectors Checklist! I made this checklist for myself to keep track of what TSR products I own. Many times was I in the position to photocopy (“Xerox”) a module or booklet that the owner didn’t wish to sell. So gradually my collection expanded with not only genuine products but also with photocopies. Since the coming of the officially digitized classic products (PDF) it is even harder to keep track of what product you own in what format. With the Collectors Checklist you will be able to sort your whole Dungeons&Dragons collection, no matter what the format is! For those out there who haven’t got a clue, here’s how to use the Collectors Checklist: TSR-Code : The product’s publishing code Sub-Code : When a product belongs to a specific group of products it carries this code Title : The product’s title (dah!) Hardcopy : Check this if you have the original item Copy : Check this if you have a copy (Xeroxcopy for instance) of the original product PDF : Check this if you have a digital copy(.pdf/.doc/etc.) of the original product HINT: you can even write down the number when you own more than one copy of a product ; ) If you think any items are missing, please mail me at [email protected] . Feel free to copy/share/print this list. Please visit these websites for the best Dungeons&Dragons archives on the Internet : http://www.acaeum.com http://home.flash.net/~brenfrow/index.htm . -

Waterdeep Dragon Heist & Dungeon of the Mad Mage

Content Catalogue Version 8.02 Waterdeep Dragon Heist & Dungeon of the Mad Mage Credits D&D Organized Play: Christopher Lindsay D&D Adventurers League Administrators: Bill Benham, Lysa Chen, Claire Hoffman Greg Marks, Alan Patrick, Sam Simpson, Travis Woodall Effective Date 31 August 2018 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. D&D Adventurers League Catalogue IT WAS OGHMA, THE GOD OF KNOWLEDGE. Although I can’t really say that I met him, I suppose, as he was drunk and fast asleep in Cousin Roffler’s back lawn – or perhaps I should say ON Cousin Roffler’s back lawn. He was a giant of an avatar, sprawled out and snoring. I wonder how you get a god drunk? —Jan, a thief, to Minsc, a barbarian What is This? The Dungeons and Dragons Adventurers League has been around for a few years now, and a lot of content has been created during that time. -

Yawning Portal Campaign: Volume 1

Yawning Portal Campaign: Volume 1 !! The Yawning Portal Campaign provides a compelling backstory and encounters to link the adventures found in Tales from the Yawning Portal into an epically deadly and epically fun campaign. Volume 1 introduces the backstory, provides a campaign hook, additional encounters and transitions for Sunless Citadel and Forge of Fury, and Safehouse, an original adventure – taking characters from level one to level five. This campaign guide is flexible. You can follow the adventures in order, pick and choose encounters to match the Yawning Portal adventures that you want to run, or use the backstory, seven encounters and adventure for a treasure hunt of your own devising! by EBrun Illustrations by Patrick Pullen ! Sample file ! ! ! ! DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2016 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Not for resale.