Michael Almereyda's Hamlet – an Attempt at Hamlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

The Story O/Hamlet

Thestory o/Hamlet The guards of ElsinoreCastle in Denmark have scen a Ghoston the bardcmenrs.Ir lookslike rhe fatherof prince -l'hev Hamlet who died only rwo monrhs bcfore. ask Horario.a youngnobleman and a friendof rhe prrnie, ro watchwith them and to talk to the Ghost.rffhen it appears. it doesnot speak, and disappears from sight. The new King of Denrnark Thc new King ofDenmark is Claudius,Hamler's uncle who hasjust ma[ied the Prince'smother, Gertrude.He allows Laertes,the son of his Lord Chamberlain,polonius. to rcturnto Parrsand urges Hamlel to castoff hismournine. Hamletis srill disrrcssed by his tarher'sdearh and decplv upsel that his mother has marriedbarelv t*o m,rnrh, afterwards.He longsfor deathand cundemnshis mother 'Fraihy, with the words, rhy nameis woman., Hamlet's lorying for death O! that this too too sol llesh toutrt nelt, ThalL)and r.sobe itseu inb a dn) . IInr ueary, shle,tat, and u,tfrolitubb Seemb mea fie usesof rhis;^orLl. Acrr Scii Poloniusbids farewellto hisson.advising him on howa youngman shouldbehave. Polonius's advice to his son l,leithera bonote4 nor a lealer be; Forloa ofi tosesbofi ilsetf dndfri.n t, And bonuA s dul\ th, eds ol hu,bart,j. Thr oboreall. to rhnc mv sctlbe rruc, And mustfoll@^, ttsthe nigtu rheda|, Thoucanst not fien befalse to anJma . Act r Sciii A ghostly rneeting Hamlet,meanwhile, has gone ro the castlebattlcments with Horatio. Vhen the Ghosrappears, he speaksro Hamlel, as the spirit of his dead farhcr. The Ghosrrells how he was l14 hr\ asks.llrrnltt 1o rcvtntle murdcrcd h\ (lhudius lnd lecp thc mcctingsccrer i""ii.-ii"*r",':i;.'. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’S Hamlet

The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mosley, Joseph Scott. 2017. The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33826315 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet Joseph Scott Mosley A Thesis in the Field of Dramatic Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2017 © 2017 Joseph Scott Mosley Abstract The aim of the proposed thesis will be to examine the complex and compelling relationship between fathers and sons in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This study will investigate the difficult and challenging process of forming one’s own identity with its social and psychological conflicts. It will also examine how the transformation of the son challenges the traditional family model in concert or in discord with the predominant philosophy of the time. I will assess three father-son relationships in the play – King Hamlet and Hamlet, Polonius and Laertes, and Old Fortinbras and Fortinbras – which thematize and explore filial ambivalence and paternal authority through the act of revenge and mourning the death of fathers. -

Cinematic Hamlet Arose from Two Convictions

INTRODUCTION Cinematic Hamlet arose from two convictions. The first was a belief, confirmed by the responses of hundreds of university students with whom I have studied the films, that theHamlet s of Lau- rence Olivier, Franco Zeffirelli, Kenneth Branagh, and Michael Almereyda are remarkably success- ful films.1 Numerous filmHamlet s have been made using Shakespeare’s language, but only the four included in this book represent for me out- standing successes. One might admire the fine acting of Nicol Williamson in Tony Richard- son’s 1969 production, or the creative use of ex- treme close-ups of Ian McKellen in Peter Wood’s Hallmark Hall of Fame television production of 1 Introduction 1971, but only four English-language films have thoroughly transformed Shakespeare’s theatrical text into truly effective moving pictures. All four succeed as popularizing treatments accessible to what Olivier’s collabora- tor Alan Dent called “un-Shakespeare-minded audiences.”2 They succeed as highly intelligent and original interpretations of the play capable of delight- ing any audience. Most of all, they are innovative and eloquent translations from the Elizabethan dramatic to the modern cinematic medium. It is clear that these directors have approached adapting Hamlet much as actors have long approached playing the title role, as the ultimate challenge that allows, as Almereyda observes, one’s “reflexes as a film-maker” to be “tested, battered and bettered.”3 An essential factor in the success of the films after Olivier’s is the chal- lenge of tradition. The three films that followed the groundbreaking 1948 version are what a scholar of film remakes labels “true remakes”: works that pay respectful tribute to their predecessors while laboring to surpass them.4 As each has acknowledged explicitly and as my analyses demonstrate, the three later filmmakers self-consciously defined their places in a vigorously evolving tradition of Hamlet films. -

December 2020 Download

December 2020 Program Updates from VP and Program Director Doron Weber FILM Son of Monarchs Awarded 2021 Sloan Feature Film Prize at Sundance Son of Monarchs has been chosen as the Sloan Feature Film Prize winner at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, to be awarded in January at this year’s virtual festival. The feature film, directed and written by filmmaker and scientist Alexis Gambis, follows a Mexican biologist who studies butterflies at a NYC lab as he returns home to the Monarch forests of Michoacán. The film was cited by the jury “for its poetic, multilayered portrait of a scientist’s growth and self-discovery as he migrates between Mexico and NYC working on transforming nature and uncovering the fluid boundaries that unite past and present and all living things.” This year’s Sloan jury included MIT researcher and protagonist of the new Sloan documentary Coded Bias Joy Buolamwini, Associate Professor in Chemistry at CUNY Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center Mandë Holford, and Sloan-supported filmmakers Aneesh Chaganty (Searching), Lydia Dean Pilcher (Radium Girls), and Lena Vurma (Adventures of a Mathematician). Son of Monarchs will be included in the 2021 Sundance Film Festival program and will be recognized at the closing night award ceremony as the Sloan winner. The Sloan Feature Film Prize, one of only six juried prizes at Sundance, is supported by a 2019 grant to the Sundance Institute. Ammonite Wins Sloan Science in Cinema Award at SFFILM This year’s SFFILM Sloan Science in Cinema Prize, which recognizes the compelling depiction of science in a narrative feature film, was awarded to Ammonite. -

The Dramatic Space of Hamlet's Theatre

Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica, 4, 1 (2012) 59-75 “The Play’s the Thing” The Dramatic Space of Hamlet’s Theatre Balázs SZIGETI Eötvös Loránd University Department of English Studies [email protected] Abstract. In my paper I investigate the use of the dramatic space in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The tragedy will be observed with the method of “pre-performance criticism,” which first and foremost makes use of the several potentials a play contains and puts on display before an actual performance; it offers, also in the light of the secondary literature, various ways of interpretation, resulting from the close-reading of the play and considers their possible realizations in the space of the stage both from the director’s and the actor’s point of view, including the consequences the respective lines of interpretation may have as regards the play as a whole. Hamlet does not only raise the questions of the theatrical realization of a play but it also reflects on the ontology of the dramatic space by putting the performance of The Mousetrap-play into one of its focal points and scrutinises the very interaction between the dramatic space and the realm of the audience. I will discuss the process how Hamlet makes use of his private theatre and how the dramatic space is transformed as The Murder of Gonzago turns into The Mousetrap-performance. Keywords: Hamlet; The Mousetrap; dramatic space; pre-performance criticism Shakespeare’s Hamlet1 does not only raise the questions of the theatrical realization of a play but it also reflects on the ontology of the dramatic space by putting the performance of The Mousetrap-play into one of its focal points and 1 In the present paper I quote the play according to the Norton Shakespeare edition (Greenblatt et. -

Hamlet on the Screen Prof

Scholars International Journal of Linguistics and Literature Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Linguist Lit ISSN 2616-8677 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3468 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijll Review Article Hamlet on the Screen Prof. Essam Fattouh* English Department, Faculty of Arts, University of Alexandria (Egypt) DOI: 10.36348/sijll.2020.v03i04.001 | Received: 20.03.2020 | Accepted: 27.03.2020 | Published: 07.04.2020 *Corresponding author: Prof. Essam Fattouh Abstract The challenge of adapting William Shakespeare‟s Hamlet for the screen has preoccupied cinema from its earliest days. After a survey of the silent Hamlet productions, the paper critically examines Asta Nielsen‟s Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance by noting how her main character is really a woman. My discussion of the modern productions of Shakespeare begins with a critical discussion of Lawrence Olivier‟s seminal production of 1948. The Russian Hamlet of 1964, directed by Grigori Kozintsev, is shown to combine a psychological interpretation of the hero without disregarding its socio-political context. The action-film genre deployed by Franco Zeffirelli in his 1990 adaptation of the play, through a moving performance by Mel Gibson, is analysed. Kenneth Branagh‟s ambitious and well-financed production of 1996 is shown to be somewhat marred by its excesses. Michael Almereyda‟s attempt to present Shakespeare‟s hero in a contemporary setting is shown to have powerful moments despite its flaws. The paper concludes that Shakespeare‟s masterpiece will continue to fascinate future generations of directors, actors and audiences. Keywords: Shakespeare – Hamlet – silent film – film adaptations – modern productions – Russian – Olivier – Branagh – contemporary setting. -

Hamlet Study Guide Levels Two & Three Wilson Know the Characters: Hamlet – Prince of Denmark Claudius – Hamlet's Uncl

Hamlet Study Guide Levels Two & Three Wilson Know the Characters: Hamlet – Prince of Denmark Claudius – Hamlet’s Uncle; he was recently crowned king of Denmark Gertrude – Queen of Denmark; Hamlet’s mother Polonius – Advisor to the King Ophelia – Hamlet’s love interest; Polonius’ daughter Laertes – Polonius’ son Ophelia’s brother Horatio – Hamlet’s best friend; voice of reason in the play Fortinbras – Prince of Norway; wants to regain land lost by his father Courtiers: Rosencrantz – Noblemen and acquaintances of Hamlet invited to cheer him Guildenstern – up Osric - Cornelius Voltemand – Ambassador charged with going to Norway Officers, Soldiers, and Servants: Francisco – Marcellus – Soldiers who first witness the ghost while on guard Bernardo – Reynaldo – Servant to Polonius Act One, Scene One 1. What is the setting for the play? Denmark; Elsinore Castle 2. What are Bernardo and Francisco doing at the beginning of the play? They are on watch waiting for their replacements. 3. What is going on that makes this necessary? There is a military threat from Norway, in the form of Young Fortinbras. 4. Why is Horatio summoned to the roof of the castle? The want him to witness and/or validate the appearance of the ghost of the dead king. 5. What decision does Horatio make after witnessing what he does? He decides to tell young Hamlet, because he thinks the ghost will speak to him. Act One, Scene Two 6. What has recently happened in Hamlet’s family? His father died and his mother married his uncle. 7. Why is Hamlet being scolded by his uncle? His uncle feels Hamlet has been mourning his father for too long. -

Supernatural Elements in Shakespeare's Plays

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 391-395, March 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1002.22 Supernatural Elements in Shakespeare’s Plays Liwei Zhu Tianjin Polytechnic University, China Abstract—This paper analyzes the supernatural elements of Shakespeare’s plays from several aspects. It first introduces the historical background of Shakespeare’s writing career. Then, it analyzes supernatural elements in three of his great plays and introduces how the supernatural elements are represented on stage in old Elizabethan period and in modern times. Last, it provides the modern implications to the 21 st century viewers of Shakespeare’s plays. Index Terms—the supernatural elements, ghosts, Elizabethan period I. INTRODUCTION Modern humans find it difficult to believe in ghosts, witches or other supernatural beings. They couldn’t understand why people in the Elizabethan period can be so serious about these things. People’s intense fear towards the supernatural elements is probably due to the lack of physical knowledge about world they were living in. Shakespeare introduced many supernatural elements into his plays. Without looking at the reasons and motivations behind them, we wouldn’t be able to detect the plays’ underlied meanings and implications. Shakespeare’s plays are always considered to be the greatest plays in the world literary history, not only because of the beautiful language, the complex plot construction and the modern implication of their universal themes, but also because of the breathtaking literary skills applied and mysterious elements in these plays. The supernatural elements constitute a significant part of Shakespeare’s plays, whether in the romantic comedies in the early period---A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1596) or in the tragedies of the second period---Hamlet (1601), Othello (1606), Mac Beth (1606), Romeo and Juliet (1607) or in his later romance---The Tempest (1611). -

2020 Sundance Film Festival: 118 Feature Films Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 4, 2019 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL: 118 FEATURE FILMS ANNOUNCED Drawn From a Record High of 15,100 Submissions Across The Program, Including 3,853 Features, Selected Films Represent 27 Countries Once Upon A Time in Venezuela, photo by John Marquez; The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me, photo by Jake Magee; Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, courtesy of Sundance Institute; Beast Beast, photo by Kristian Zuniga; I Carry You With Me, photo by Alejandro López; Ema, courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — The nonprofit Sundance Institute announced today the showcase of new independent feature films selected across all categories for the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The Festival hosts screenings in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort, from January 23–February 2, 2020. The Sundance Film Festival is Sundance Institute’s flagship public program, widely regarded as the largest American independent film festival and attended by more than 120,000 people and 1,300 accredited press, and powered by more than 2,000 volunteers last year. Sundance Institute also presents public programs throughout the year and around the world, including Festivals in Hong Kong and London, an international short film tour, an indigenous shorts program, a free summer screening series in Utah, and more. Alongside these public programs, the majority of the nonprofit Institute's resources support independent artists around the world as they make and develop new work, via Labs, direct grants, fellowships, residencies and other strategic and tactical interventions. -

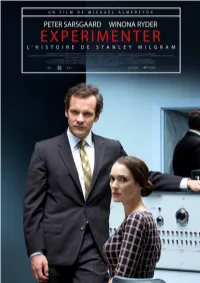

Experimenter Dp 2

!2 w w w . s e p t i e m e f a c t o r y . c o m Présente EXPERIMENTER réalisé par MICHAEL ALMEREYDA Avec PETER SARSGAARD WINONA RYDER USA - 2015 Durée : 1H30 – Format : 1:85 – Son : DOLBY 5.1 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 18 NOVEMBRE 2015 DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE SEPTIEME FACTORY BOSSA NOVA 20, rue du Neuhof Michel Burstein 67100 Strasbourg 32, Bld Saint Germain [email protected] 75005 Paris [email protected] Tel : 01 43 26 26 26 [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info !3 !4 Synopsis Yale Université, 1961, Stanley Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard) conduit une expérience de psychologie - encore majeure aujourd’hui - dans laquelle des volontaires croient qu’ils administrent des décharges électriques douloureuses à un parfait inconnu (Jim Gaffigan) attaché à une chaise, dans une autre pièce. Malgré les demandes de la victime d’arrêter, la majorité des volontaires continuent l’expérience, infligeant ce qu’elles croient être des décharges presque mortelles, simplement parce qu’un scientifique leur a demandé de le faire. A l'époque où le procès du Nazi Eichmann est diffusé à la télévision jusque dans les foyers de millions d'américains, la théorie développée par le scientifique Milgram, qui explore la tendance des individus à se soumettre à une autorité, provoque une vive émotion dans l'opinion publique et la communauté scientifique. Célébré par nombre de ses confrères il est vilipendé par d'autres. Stanley Milgram est alors accusé de tromperie et de manipulation. Son épouse Sasha (Winona Ryder) le soutient dans cette période de trouble.