Cinematic Hamlet Arose from Two Convictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

The District Messenger the District Messenger

The District Messenger THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON no. 72 19th April 1988 210, Rainsford Road, Chelmsford, Essex. CM1 2PD Tony Medawar has sent me some very expensive publicity for a very expensive series of handmade puppets, including Holmes, by Jane and Jorge of 122 Church Way, Iffley, Oxford 0X4 4EG. The figures are 70cm tall (2 foot 6?), of ceramic, wood & wool, and can be had as puppets, standing figures or automata. Prices £400 and up. A photo shows Holmes to be sensationally ugly. Catherine Cooke reminds me that Val Andrews ' SHERLOCK HOLMES 8c THE EMINENT THESPIAN (Ian Henry, £8.95) is now out, and points out that Rosalind Ashe 's LITERARY HOUSES (Dragon 's World, £8.95 or £5.95 paperback) has a guided tour of Baskerville Hall. The State Library of Victoria, Australia recently staged a Sherlock Holmes Centenary Exhibition & has published a 56 page commemorative catalogue, HOLMES AWAY FROM HOME at Aus. $8 + Aus. $6 post overseas (limited edition Aus. $75 + Aus. $10 post). I hope to review this soon. Two other books I 've not yet mentioned are M.J. Trow 's 5th Inspector Lestrade novel, LESTRADE & THE BROTHER OF DEATH (Macmillan, £9-95) and Arthur Conan Doyle 's DOCTORS: TALES FROM MEDICAL LIFE (Greenhill Books, £8.95), both now out. Vosper Arthur (Spynishlake, Doddiscombsleigh, Exeter, Devon) has 7 spare copies of the prog- ramme for SHERLOCKS LAST CASE, recently produced at the Nederlander Theater in New York, available to first claimants at £1.50 each inclusive. Good reports from both Carol Whitlam & David Stuart Davies of the 1st meeting proper of the Northern Musgraves. -

Losing Willwalking a Tightrope to Fame

A&E [email protected] thursday, 29 november, 2007 Social Losing Will walking a tightrope to fame intercourSe Joe Vanderhelm talks botched audio, improvising scripts, and hoping that his locally filmed Grant MacEwan/University of Alberta Big Band Concert flick—complete with Edmonton scenery and music—has enough pull to reach cult status Monday, 3 December at 7:30pm John L Haar Theatre (10045 155 Street) filmpreview Performing together on the same stage, the Grant Losing Will MacEwan big band and the University of Alberta Runs 7–9 December big band will combine this coming Monday, creat- Directed by Mike Robertson and Arlen Konopaki ing a band the size of which can’t be described with Starring Arlen Konopaki, Joe Vanderhelm, and a simple adjective like big. Rather, it would require a Julian Faid conglomeration of descriptors, like “ginormous” or Metro Cinema “hugelarge.” Conducted by professors Raymond Baril and Dr Tom Dust, the humungollossal group will play BRYAN SAUNDERS a wide selection of jazz standards and should provide Arts & Entertainment Staff an entertaining night for fans of the genre. As Joe Vanderhelm, one of the stars of Highwire Films’ Losing Will, puts it, producing a local Trooper independent movie is a lot like walking on a Thursday, 29 November at 8pm tightrope. Century Casino (13103 Fort Road) “When you think of [a] high-wire act, there’s the chance of falling and the chance of failure, Here they come, classic rock group Trooper, driving in a but that always just makes it all the more inter- bright white sports car on their way through Edmonton. -

THE “TENET” THEORY Written by Esmarelda Villalobos

THE “TENET” THEORY Written by Esmarelda VillaLobos WARNING: MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD. “Tenet” begins with an attack on the arts. It is the first event in the film, right out of the gate, that sets the tone for the rest of the movie. In fact, in this film there are multiple attacks on art, but in the first few minutes of this topsy-turvy ride, we as the audience witness some kind of terrorist attack that occurs during the preparations for an orchestral performance somewhere in Russia, which, given the number of public shootings and horrific terrorist attacks that have plagued the world throughout the last decade, is not that far of a stretch from the truth. The first line of the film is “Time to wake up the Americans” to which we are now introduced to John David Washington’s character as The Protagonist. Through a series of what seems to be party-switching and criss-crossery (if that’s even a word), John David Washington is eventually caught. While under capture and interrogation, The Protagonist decides to sacrifice his own life for the good of the cause and swallow a cyanide pill given to him by the CIA. Cut to black. When we as the audience come back, John David Washington is in a hospital bed on a very large ship, somewhere beyond the sea. Now, on first viewing if you are to watch this film, you believe everything that is said – the cyanide pill is a fake, his taking it was a test to see if he would sacrifice himself in order to avoid torture and potentially give up secrets – which he did. -

A Pinewood Dialogue with Kenneth Branagh and Michael Caine

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH KENNETH BRANAGH AND MICHAEL CAINE The prolific and legendary actor Michael Caine starred in both the 2007 film version of Sleuth (opposite Jude Law) and the 1972 version (opposite Laurence Olivier). In the new version, an actors’ tour de force directed by Kenneth Branagh and adapted by playwright Harold Pinter, Caine took the role originally played by Olivier. A riveting tale of deception and deadly games, this thriller about an aging crime novelist and a young actor in love with the same woman is essentially about the mysteries of acting and writing. In this discussion, Branagh and Caine discussed their collaboration after a special preview screening. A Pinewood Dialogue following a screening BRANAGH: Rubbish, of course. Rubbish. of Sleuth, moderated by Chief Curator David Schwartz (October 3, 2007): SCHWARTZ: Well, we’ll see, we’ll see. Tell us about how this project came about. It’s an interesting MICHAEL CAINE: (Applause) pedigree, because in a way, it’s a new version, an Good evening. adaptation, of a play. It seems like it’s going to be a remake of the film, but Harold Pinter, of course, KENNETH BRANAGH: Good evening. is the author here. DAVID SCHWARTZ: Welcome and congratulations BRANAGH: As you may have seen from the credits, on a riveting, very entertaining movie. one of the producers is Jude Law. He was the one who had the idea of making a new version, BRANAGH: Thank you. and it was his idea to bring onboard a man he thought he’d never get to do it, but Nobel Prize- CAINE: Thank you. -

Widescreen Weekend 2008 Brochure (PDF)

A5 Booklet_08:Layout 1 28/1/08 15:56 Page 41 THIS IS CINERAMA Friday 7 March Dirs. Merian C. Cooper, Michael Todd, Fred Rickey USA 1952 120 mins (U) The first 3-strip film made. This is the original Cinerama feature The Widescreen Weekend continues to welcome all which launched the widescreen those fans of large format and widescreen films – era, and is about as fun a piece of CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and IMAX – Americana as you are ever likely and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of to see. More than a technological curio, it's a document of its era. the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. HAMLET (70mm) Sunday 9 March Widescreen Passes £70 / £45 Dir. Kenneth Branagh GB/USA 1996 242 mins (PG) Available from the box office 0870 70 10 200 Kenneth Branagh, Julie Christie, Derek Jacobi, Kate Winslet, Judi Patrons should note that tickets for 2001: A Space Odyssey are priced Dench, Charlton Heston at £10 or £7.50 concessions Anyone who has seen this Hamlet in 70mm knows there is no better-looking version in colour. The greatest of Kenneth Branagh’s many achievements so 61 far, he boldly presents the full text of Hamlet with an amazing cast of actors. STAR! (70mm) Saturday 8 March Dir. Robert Wise USA 1968 174 mins (U) Julie Andrews, Daniel Massey, Richard Crenna, Jenny Agutter Robert Wise followed his box office hits West Side Story and The Sound of Music with Star! Julie 62 63 Andrews returned to the screen as Gertrude Lawrence and the film charts her rise from the music hall to Broadway stardom. -

December 2020 Download

December 2020 Program Updates from VP and Program Director Doron Weber FILM Son of Monarchs Awarded 2021 Sloan Feature Film Prize at Sundance Son of Monarchs has been chosen as the Sloan Feature Film Prize winner at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, to be awarded in January at this year’s virtual festival. The feature film, directed and written by filmmaker and scientist Alexis Gambis, follows a Mexican biologist who studies butterflies at a NYC lab as he returns home to the Monarch forests of Michoacán. The film was cited by the jury “for its poetic, multilayered portrait of a scientist’s growth and self-discovery as he migrates between Mexico and NYC working on transforming nature and uncovering the fluid boundaries that unite past and present and all living things.” This year’s Sloan jury included MIT researcher and protagonist of the new Sloan documentary Coded Bias Joy Buolamwini, Associate Professor in Chemistry at CUNY Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center Mandë Holford, and Sloan-supported filmmakers Aneesh Chaganty (Searching), Lydia Dean Pilcher (Radium Girls), and Lena Vurma (Adventures of a Mathematician). Son of Monarchs will be included in the 2021 Sundance Film Festival program and will be recognized at the closing night award ceremony as the Sloan winner. The Sloan Feature Film Prize, one of only six juried prizes at Sundance, is supported by a 2019 grant to the Sundance Institute. Ammonite Wins Sloan Science in Cinema Award at SFFILM This year’s SFFILM Sloan Science in Cinema Prize, which recognizes the compelling depiction of science in a narrative feature film, was awarded to Ammonite. -

Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 3 Issue 2 October 1999 Article 2 October 1999 Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Mark Goodacre University of Birmingham, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Goodacre, Mark (1999) "Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol3/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Abstract Jesus Christ Superstar (dir. Norman Jewison, 1973) is a hybrid which, though influenced yb Jesus films, also transcends them. Its rock opera format and its focus on Holy Week make it congenial to the adaptation of the Gospels and its characterization of a plausible, non-stereotypical Jesus capable of change sets it apart from the traditional films and aligns it with The Last Temptation of Christ and Jesus of Montreal. It uses its depiction of Jesus as a means not of reverence but of interrogation, asking him questions by placing him in a context full of overtones of the culture of the early 1970s, English-speaking West, attempting to understand him by converting him into a pop-idol, with adoring groupies among whom Jesus struggles, out of context, in an alien culture that ultimately crushes him, crucifies him and leaves him behind. -

2020 Sundance Film Festival: 118 Feature Films Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 4, 2019 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL: 118 FEATURE FILMS ANNOUNCED Drawn From a Record High of 15,100 Submissions Across The Program, Including 3,853 Features, Selected Films Represent 27 Countries Once Upon A Time in Venezuela, photo by John Marquez; The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me, photo by Jake Magee; Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, courtesy of Sundance Institute; Beast Beast, photo by Kristian Zuniga; I Carry You With Me, photo by Alejandro López; Ema, courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — The nonprofit Sundance Institute announced today the showcase of new independent feature films selected across all categories for the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The Festival hosts screenings in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort, from January 23–February 2, 2020. The Sundance Film Festival is Sundance Institute’s flagship public program, widely regarded as the largest American independent film festival and attended by more than 120,000 people and 1,300 accredited press, and powered by more than 2,000 volunteers last year. Sundance Institute also presents public programs throughout the year and around the world, including Festivals in Hong Kong and London, an international short film tour, an indigenous shorts program, a free summer screening series in Utah, and more. Alongside these public programs, the majority of the nonprofit Institute's resources support independent artists around the world as they make and develop new work, via Labs, direct grants, fellowships, residencies and other strategic and tactical interventions. -

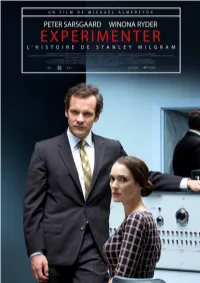

Experimenter Dp 2

!2 w w w . s e p t i e m e f a c t o r y . c o m Présente EXPERIMENTER réalisé par MICHAEL ALMEREYDA Avec PETER SARSGAARD WINONA RYDER USA - 2015 Durée : 1H30 – Format : 1:85 – Son : DOLBY 5.1 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 18 NOVEMBRE 2015 DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE SEPTIEME FACTORY BOSSA NOVA 20, rue du Neuhof Michel Burstein 67100 Strasbourg 32, Bld Saint Germain [email protected] 75005 Paris [email protected] Tel : 01 43 26 26 26 [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info !3 !4 Synopsis Yale Université, 1961, Stanley Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard) conduit une expérience de psychologie - encore majeure aujourd’hui - dans laquelle des volontaires croient qu’ils administrent des décharges électriques douloureuses à un parfait inconnu (Jim Gaffigan) attaché à une chaise, dans une autre pièce. Malgré les demandes de la victime d’arrêter, la majorité des volontaires continuent l’expérience, infligeant ce qu’elles croient être des décharges presque mortelles, simplement parce qu’un scientifique leur a demandé de le faire. A l'époque où le procès du Nazi Eichmann est diffusé à la télévision jusque dans les foyers de millions d'américains, la théorie développée par le scientifique Milgram, qui explore la tendance des individus à se soumettre à une autorité, provoque une vive émotion dans l'opinion publique et la communauté scientifique. Célébré par nombre de ses confrères il est vilipendé par d'autres. Stanley Milgram est alors accusé de tromperie et de manipulation. Son épouse Sasha (Winona Ryder) le soutient dans cette période de trouble. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability.