Arbitrability and Public Policy in Regard to the Recognition And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience Lingnan University, Located in Tuen

e r X p i e E n c e Index e l c X Explore Hong Kong 1 E Experience 2 Excel @ 10 E X p l o r e Fast facts 11 L ingn an U ST nive ART rs HE ity RE! L ingn an U ST nive ART rs HE ity RE! Welcome to Hong Kong Experience Lingnan University, located in Tuen Mun, offers a stimulating and thought-provoking liberal arts education. We are the only university in Hong Kong to offer a dedicated liberal arts education. Our goal is to cultivate in our graduates the skills and sensibilities necessary to successfully pursue their career goals and take their place as socially responsible citizens in today’s rapidly evolving global environment. Lively and outward-looking, the university is located on an award-winning campus that visually represents our East-West orientation. Courses are offered by 16 departments in the Faculties of Arts, Business and Social Sciences, the Core Curriculum and General Education Explore Office and two language centres. Hong Kong Mission and vision Lingnan University is committed to the provision of quality education The geographical position of Hong Kong, a vibrant world city situated at the mouth of distinguished by the best liberal arts the Pearl River Delta on the coast of southern China, has made it a gateway between traditions. We adopt a whole-person East and West, turning it into one of the world’s most cosmopolitan metropolises. approach to education that enables our students to think, judge, care Bi-literacy and tri-lingualism thrive in Hong Kong. -

Legal Hybridity in Hong Kong and Macau Ignazio Castellucci

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:22 p.m. McGill Law Journal Revue de droit de McGill Legal Hybridity in Hong Kong and Macau Ignazio Castellucci Volume 57, Number 4, June 2012 Article abstract The article aims to compare the case of the two Chinese Special Administrative URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013028ar Regions (SARs) of Hong Kong and Macau against the theoretical grid developed DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1013028ar by Vernon V. Palmer to describe the “classical” civil law-common law mixed jurisdictions. The results of the research include an acknowledgement of the See table of contents progressive hybridization of the legal systems of Hong Kong and Macau, hailing from the English common law and the Portuguese civil law tradition, respectively, by infiltration of legal models and ideologies from Mainland Publisher(s) China. The research also leads to a critical revision and refinement of the McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill methodology and tools developed by Palmer in order to make them applicable to a wider range of processes of legal hybridization beyond “classical” mixes, ISSN and to a better appreciation of how transitional political and institutional phases play a critical role inlegal “mixity” or hybridity. 0024-9041 (print) 1920-6356 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Castellucci, I. (2012). Legal Hybridity in Hong Kong and Macau. McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill, 57(4), 665–720. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013028ar Copyright © Ignazio Castellucci, 2012 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

The Case of the Second Person Plural Form Memòria D’ Investigació

Pronominal variation in Southeast Asian Englishes: the case of the second person plural form Memòria d’ investigació Autora: Eva María Vives Centelles Directora: Cristina Suárez Gómez Departament de Filologia Espanyola, Moderna i Clàssica Universitat de les Illes Balears Data 10 Gener 2014 OUTLINE 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………...........2 2. Brief history of World Englishes ……………………………………............4 3. Theoretical framework: Models of analysis………………………………...6 3.1 Kachru’s Three Concentric Circles……………………………..7 3.2.McArthur’s Circle of World English…………………………..10 3.3.Görlach’s A circle of International English…………………….12 3.4.Schneider’s Dynamic Model of Postcolonial Englishes……….14 4. East and South-East Asian Englishes………………………………………25 4.1. Indian English (IndE) .…………………………………………26 4.2. Hong Kong English (HKE)…………………………………….34 4.3 Singapore English (SingE)……………………………………...38 4.4. The Philippines English (PhilE)………………………………44 5. Second person plural forms in the English language……………………....48 6. Description of the corpus and data analysis……………………………….58 6.1. Description of the corpus………………………………………58 6.2. Data Analysis…………………………………………………..61 7. Conclusions……………………………………………………...................80 8. Limitations of the study…………………………………………………….84 9. Questions for further research……………………………………………...84 10. References.....................................................................................................85 11. Appendix…………………………………………………………………...93 1 1. INTRODUCTION When the American president John Adams (1735-1826) -

Language Surveys and Hong Kong's Changing Linguistic Profile

Bilingualism and multilingualism in the HKS R: language surveys and Hong Kong's changing linguistic profile John Bacon-Shone, University of Hong Kong Kingsley Bolton1 Stockholm University Introduction This paper attempts to provide an accurate description of the general language situation in Hong Kong from a macrosociolinguistic perspective, that is, describing the broad picture of how many languages are spoken, how many people speak such languages, as well as a range of other issues related to language acquisition and use in within the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). In an earlier study, we discussed the historical background to language surveys and language censuses from the time of the first language census in 1911 up to the era of late British colonialism in the 1990s (Bacon Shone and Bolton 1998). In this present study we pay special attention to the dynamics of language spread and language use in the period 1983- 2003, with empirical data that is primarily census data and language survey data from that period. Despite the limitations of the survey method, we argue that census and survey information has a useful role to play in discussions of local language issues in both academia and the public arena. The historical background In many societies worldwide, language issues often function as a touchstone for a range of other questions, questions that are not only linguistic in substance, but are often linked to social and political ideologies. This is particularly true of Hong Kong, which has experienced Bacon-Shone, L & Bolton, K. (2008). Bilingualism and multilingualism in the HKSAR: Language surveys and Hong Kong's changing linguistic profile. -

Language and Place-Making: Public Signage in the Linguistic Landscape of Windhoek's Central Business District

LANGUAGE AND PLACE-MAKING: PUBLIC SIGNAGE IN THE LINGUISTIC LANDSCAPE OF WINDHOEK’S CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT by Danielle Zimny Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of General Linguistics in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Marcelyn Oostendorp Co-supervisor: Ms Robyn Berghoff December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Danielle Zimny Date: December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Marcelyn Oostendorp, and co-supervisor, Ms Robyn Berghoff, for providing me with valuable guidance throughout the phases of this study. I would additionally like to thank Stellenbosch University for granting me a merit bursary for the duration of my Master’s course. Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Investigating linguistic landscapes (LLs) has primarily been a matter of assessing language use in public signage. In its early days research in the field focused largely on quantitative analysis and typically drew direct relations between the prevalence (or absence) of languages in the public signs of an LL and the ethnolinguistic vitality of such languages. -

THE ROLE of READING in ENHANCING ENGLISH SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING of ORDINARY LEVEL LEARNERS in NAMIBIA By

THE ROLE OF READING IN ENHANCING ENGLISH SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING OF ORDINARY LEVEL LEARNERS IN NAMIBIA By Sylvia Ndapewa Ithindi Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR Faculty of Education Department of Humanities Education University of Pretoria SUPERVISOR: Dr A. Engelbrecht CO-SUPERVISOR: Dr L.J. de Jager August 2019 Declaration of authorship I, Sylvia Ndapewa Ithindi, hereby declare that this thesis entitled, The role of reading in enhancing English Second Language learning in Namibia, which I hereby submit for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Humanities Education, at the University of Pretoria, is my own work and has not previously been submitted by me for a degree at this or any other tertiary institution. i Ethics certificate ii Language editor Cell: 083 455 3723 Address: 9 Tiger Road Monument Park 0181 PRETORIA E-mail: [email protected] To whom it may concern This is to confirm that I, MJ de Jager, edited the language in the PhD dissertation, The role of reading in enhancing English second language learning in Namibia, by Sylvia Ndapewa Ithindi. The onus was on the author to attend to all my suggested changes and queries. Furthermore, I do not take responsibility for any changes effected in the document after the fact. MJ DE JAGER 5 October 2019 iii Dedication This study is dedicated to my children, Aino Ndamana Tangi Matheus, Simon Nanyooshili Tangeni Matheus, and my nephew Samuel Kalitheni Shiindi, in the hope that they will all complete their studies and lead successful independent, career lives. iv Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all those who love and supported me and made my long, yet fruitful journey, worth completing. -

The Background to Language Change in Hong Kong

The Background to Language Change in Hong Kong Godfrey Harrison and Lydia K.H. So Speech & Hearing Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, 5/F Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong This paper gives the background to language change in Hong Kong. It surveys the great changes that have taken place over the last 50 years and it situates Hong Kong as the greatest of Cantonese cities. This approach makes apparent how fast and how much Hong Kong has changed and is changing demographically, economically, politically, socially and technologically. Because language and at least four of these five aspects are interwoven, the need to deal with language in Hong Kong has been inescapable even if its manifestations were often unpredictable. The paper also reminds the reader of the greater context, showing some of the complex exchange networks that bind the Cantonese language community and making clear Hong Kong’s central position in intra-Chinese relations. Introduction Hong Kong, a sliver of Asian mainland and a clutch of nearby islands, has an area of 1092 square kilometres (422 square miles): much smaller than Majorca or Rhode Island but notably bigger than Anglesey. Its population is 6.3 million people (cf. Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics , April 1996): a little fewer than Greater London’s, somewhat more than that of the San Francisco-Oakland metropolis’. Hong Kong, in the Pearl River delta, borders the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, set up in Guangdong Province, in the People’s Republic of China, and is just south of the tropic of Cancer on the western rim of the Pacific Ocean. -

Developing a Supplementary Guide to the Chinese Language Curriculum for Non-Chinese Speaking Students

LC Paper No. CB(2)1238/07-08(01) Consultation Paper on Developing a Supplementary Guide to the Chinese Language Curriculum for Non-Chinese Speaking Students Prepared by the Curriculum Development Council Recommended for use in schools by the Education Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong SAR January 2008 1 2 Contents Preamble 1 Chapter I – Introduction 1.1 Purpose 3 1.2 Background 4 1.2.1 Non-Chinese Speaking (NCS) Students in Hong Kong 4 1.2.2 The Language Education Policy of Hong Kong 4 Chapter II – The Chinese Language and Chinese Language Learning 2.1 Characteristics of the Chinese Language 7 2.1.1 Linguistic Characteristics of Modern Chinese Language 7 2.1.2 The Spoken Language of Chinese 9 2.1.3 The Chinese Script 9 2.2 Features of Chinese Language Learning 10 2.2.1 Learning Chinese as the Mother Language 10 2.2.2 Learning Chinese as a Second Language 10 Chapter III – Experiences of Chinese Language Learning for Non-Chinese Speaking Students 3.1 Experiences in Mainland China 13 3.1.1 Background 13 3.1.2 Experiences 13 3.2 Experiences in Taiwan 15 3.2.1 Background 15 3.2.2 Experiences 15 3.3 Experiences in Singapore 15 3.3.1 Background 15 3.3.2 Experiences 16 3.4 The International Scene 16 3.5 The Situation of Chinese Language Learning for NCS Students in Hong Kong Schools 16 3.5.1 The Chinese Language Education Curriculum Framework and School Experiences 16 3.5.2 Successful Cases and Attainment of Chinese Language Learning for NCS Students 20 3.5.3 Major Concerns of Chinese Language Learning for NCS Students 21 3.6 Existing Resources -

Towards a Bilingual Legal System—The Development of Chinese Legal Language

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 19 Number 2 Symposium—July 1, 1997: Hong Kong and the Unprecedented Transfer of Article 4 Sovereignty 1-1-1997 Towards a Bilingual Legal System—The Development of Chinese Legal Language Anne S.Y. Cheung Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anne S.Y. Cheung, Towards a Bilingual Legal System—The Development of Chinese Legal Language, 19 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 315 (1997). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol19/iss2/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards a Bilingual Legal System-The Development of Chinese Legal Language ANNE S.Y. CHEUNG" I. INTRODUCTION English has been the language of the ruling class since Hong Kong first became a British colony in 1842.' The exclusive use of English in legislation and judicial proceedings has resulted in "linguistic apartheid" and has alienated Hong Kong's local popu- lation, which is ninety-eight percent ethnic Chinese, 2 from the legal system. Local subjects who are not proficient in English are disad- vantaged in their dealings and communications with the govern- ment. Most senior government officials are only able to draft of- ficial documents in English because they were trained and employed under the British colonial administration. -

A Phenomenological Study of How Black South African University

A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF HOW BLACK SOUTH AFRICAN UNIVERSITY STUDENTS EXPERIENCE CULTURAL IDENTITY IN AN ENGLISH-MEDIUM INSTRUCTION CONTEXT by Arthur Atwater Kent Cason Jr. Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University 2021 2 A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF HOW BLACK SOUTH AFRICAN UNIVERSITY STUDENTS EXPERIENCE CULTURAL IDENTITY IN AN ENGLISH-MEDIUM INSTRUCTION CONTEXT by Arthur Atwater Kent Cason Jr. A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2021 APPROVED BY: Lucinda S. Spaulding, Ph.D., Committee Chair James A. Swezey, Ed.D., Committee Member 3 ABSTRACT The purpose of this phenomenological study was to describe the experience of cultural identity in an English-medium instruction context for Black university students in South Africa. Data were collected from 10 Black South African university students representing a cross-section of South African society. In-depth individual interviews were used as the primary data collection method complemented by a focus group interview and self-reflection letters written to a hypothetical new student in which the participant recalls his or her experience with cultural identity. Data analysis followed Moustakas’ methodology involving bracketing biases, horizonalization, organizing and classifying significant statements into themes, writing the textural and structural descriptions of participants’ experiences, then integrating the textural and structural descriptions into a unified statement of the essences of the experience of the phenomenon. The findings from this study demonstrate that English as a foreign language student’s cultural identity negotiation is influenced by a complex and intense interaction of multiple cultures. -

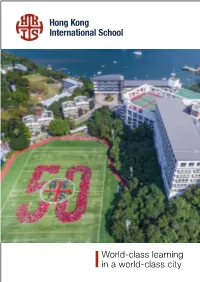

World-Class Learning in a World-Class City Our Mission

World-class learning in a world-class city Our Mission Dedicating our minds to inquiry, our hearts to compassion, and our lives to service and global understanding An American-style education, grounded in the Christian faith and respecting the spiritual lives of all Our Vision HKIS will be a leading place of learning that inspires a socially engaged community of collaborative, creative and resilient learners dedicated to realizing their full potential. Contents 1 About Our School 3 Core Values 3 Student Learning Results 4 Learning Principles and Practices Our Mission 5 Our Program Dedicating our minds to inquiry, our hearts to compassion, and our lives to service and global understanding 9 Our Faculty An American-style education, grounded in the Christian faith and respecting the spiritual lives of all 11 Religious Education at HKIS Our Vision 13 Performance Appraisal HKIS will be a leading place of learning 15 Living in Hong Kong that inspires a socially engaged community of collaborative, creative and resilient learners dedicated to realizing their full potential. About Our School A co-educational private day school grounded in the Christian faith, Hong Kong International School (HKIS) serves Reception 1 through Grade 12 students from around the world seeking an American college- preparatory education. HKIS is accredited by the United States’ Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) and is a member of the East Asia Regional Council of Overseas Schools (EARCOS). Serving over 2,800 students, HKIS has two campuses on the south side of Hong Kong Island: the Lower and Upper Primary Schools are located in Repulse Bay, while the Middle and High Schools are in Tai Tam. -

Bilingual’ Hong Kong from Bowring to Frisolac

It Beaken jiergong 70 – 2008 nr 1/2 179-194 Fryslân in Asia? ‘Bilingual’ Hong Kong from Bowring to Frisolac Kees Kuiken For Thijs Kuiken, Hong Konger and global pathologist Samenvatting (summary in Dutch) In de jaren 1960 werd de Britse kroonkolonie Hongkong opgeschrikt door gewelddadige rellen. Het vuur was opgestookt door plaatselijke volgelingen van het Maoïstische schrikbewind in China. Niettemin rees de vraag hoe de afstand tussen de Britse bestuurders en de grotendeels Chinese inwoners van Hongkong kon worden verkleind. Vanaf de jaren 1970 werd daartoe een even pragmatisch als eff ectief taalbeleid ontwikkeld. Lang voor de overdracht van Hongkong aan China (1997) werd het Chinees naast het Engels de offi ciële taal in Hongkong. Op alle bestuursniveaus verrichtten speciale taalambtenaren tolk- en vertaaldiensten. Kort voor de overdracht waren alle plaatselijke wetten in beide talen beschikbaar op het internet. Omdat Hongkong met zijn status aparte een ander rechtsbestel heeft dan de rest van China, werden en worden daarvoor ook nieuwe termen ontwikkeld. Sinds de ook in Friesland welbekende Sir John Bowring (1792-1872) als eerste en voorlopig enige Britse gouverneur van Hongkong de moeite nam om een mondje Chinees te leren, is op dit gebied dus veel verbeterd. Na 1997 wordt van Hongkongse ambtenaren verwacht dat ze niet alleen het Engels en de plaatselijke spreektaal (Kantonees) kunnen communiceren, maar ook in het Algemeen Beschaafd Chinees (‘Mandarijns’). Voor het Kantonees geldt daarbij het dialect van de nabijgelegen stad Guangzhou als norm. Het taallandschap is echter vanouds veel complexer dan deze ambtelijke twee- of driedeling zou doen vermoeden. Naast ‘Standaard-Kantonees’ worden allerlei Zuidchinese streektalen of dialecten gesproken, zowel Kantonese als niet-Kantonese.