Marine Litter Strategy for the Firth of Clyde Step 1: Defining the Status Quo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalmarnock Power Station, Riverside

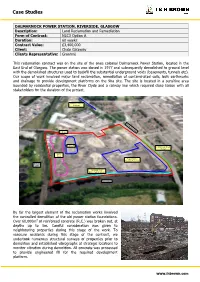

Case Studies DALMARNOCK POWER STATION, RIVERSIDE, GLASGOW Description: Land Reclamation and Remediation Form of Contract: NEC3 Option A Duration: 60 weeks Contract Value: £3,400,000 Client: Clyde Gateway Clients Representative: Grontmij This reclamation contract was on the site of the once colossal Dalmarnock Power Station, located in the East End of Glasgow. The power station was closed in 1977 and subsequently demolished to ground level with the demolished structures used to backfill the substantial underground voids (basements, tunnels etc). Our scope of work involved major land reclamation, remediation of contaminated soils, bulk earthworks and drainage to provide development platforms on the 9ha site. The site is located in a sensitive area bounded by residential properties, the River Clyde and a railway line which required close liaison with all stakeholders for the duration of the project. Dalmarnock Road Drainage Crib wall Borrow Pit Dalmarnock Road Tunnel SUDS Pond Power Station Building Footprint Railway Line Perimeter Wall River Clyde Walkway River Clyde By far the largest element of the reclamation works involved the controlled demolition of the old power station foundations. Over 60,000m3 of reinforced concrete (R.C.) was broken out, at depths up to 5m. Careful consideration was given to neighbouring properties during this stage of the work. To reassure residents during this stage of the contract, we undertook numerous structural surveys of properties prior to demolition and established vibrographs at strategic locations to monitor vibration during demolition. All concrete was processed to provide engineered fill for the required development platform. www.ihbrown.com Case Studies The removal of the substantial perimeter wall included a section which ran parallel with the River Clyde Walkway. -

City Centre – Carmyle/Newton Farmserving

64 164 364 City Centre – Carmyle/Newton Farm Serving: Tollcross Auchenshuggle Parkhead Bridgeton Newton Farm Bus times from 18 January 2016 Hello and welcome Thanks for choosing to travel with First. We operate an extensive network of services throughout Greater Glasgow that are designed to make your journey as easy as possible. Inside this guide you can discover: • The times we operate this service Pages 6-15 and 18-19 • The route and destinations served Pages 4-5 and 16-17 • Details of best value tickets • Contact details for enquiries and customer services Back Page We hope you enjoy travelling with First. What’s Changed? Service 364 - minor timetable changes before 0930. The 24 hour clock For example: This is used throughout 9.00am is shown as this guide to avoid 0900 confusion between am 2.15pm is shown as and pm time. 1415 10.25pm is shown as 2225 Save money with First First has a wide range of tickets to suit your travelling needs. As well as singles and returns, we have a range of money saving tickets that give unlimited travel at value for money prices. Single – We operate a single flat fare structure in Glasgow, and a simpler four fare structure elsewhere in the network. Buy on the bus from your driver. Return – Valid for travel off-peak making them ideal for customers who know they will only make two trips that day. Buy on the bus from your driver. FirstDay – Unlimited travel in the area of your choice making FirstDay the ideal ticket if you are making more than two trips in a day. -

To Let 3-5 Cambuslang Way (May Sell) Gateway Office Park, Cambuslang, Glasgow, G32 8Nd Suites from 5,058 Sq Ft – 10,149 Sq Ft (469.9 Sq M – 942.86 Sq M)

TO LET 3-5 CAMBUSLANG WAY (MAY SELL) GATEWAY OFFICE PARK, CAMBUSLANG, GLASGOW, G32 8ND SUITES FROM 5,058 SQ FT – 10,149 SQ FT (469.9 SQ M – 942.86 SQ M) Clowes Developments (Scotland) Ltd cwc-group.co.uk Industrial & Distribution / Office / Retail / Mixed Use / Residential / Leisure Clowes Developments (Scotland) Ltd 9 Coates Crescent, Edinburgh, EH3 7AL t / 0131 225 7265 f / 0131 225 7266 e / [email protected] cwc-group.co.uk Industrial & Distribution / Office / Retail / Mixed Use / Residential / Leisure Modern two storey office pavilion providing flexible open plan office floor space with the benefit of a high quality existing fit out capable of accommodating a wide range of sizes. Specification • Raised access floor • Gas fired central heating Ground Floor • Suspended ceiling with modern lighting • A range of open plan and cellular offices • Boardrooms with comfort cooling • Shower facilities • Staff kitchen facilities installed • Passenger lift • Excellent private car parking – 36 spaces • Cycle racks • EPC C • Equality Act compliant access First Floor Accommodation Floor Size (sq ft) Size (sq m) Ground 5058 469.90 First 5091 472.97 TOTAL 10,149 942.86 Location 3-5 Cambuslang Way is a detached office building within a prominent office park accessed from J2A of the M74 then onto Fullerton Road briefly joining Cambuslang Road and then into Cambuslang Way. Superbly sited for both Scotland’s motorway network and access into Glasgow city centre 4 miles away this location has proved popular with a wide range of local and corporate occupiers. Cambuslang and Carmyle Railway Stations together with various local bus routes are a few minutes away. -

Rivers and Streams Play an Important Part in the Recreation 6 Paisley Fulfil Conditions Under the Water Framework Directive and Is Being and Amenity Value of an Area

Current Status - UK and Local A wide variety of riverine habitats occurs in the LBAP Partnership area, ranging from fast flowing upland The River Calder feeds Castle Semple Loch with smaller contributions streams to slow flowing deep sections of river. In this area the main rivers are the White Cart Water, Black coming from the overflows of the Kilbirnie and Barr Lochs. Barr Loch Cart Water, Gryfe and Calder. They are relatively small rivers with the longest being the White Cart Water, was once a meadow with the Dubbs Water draining Kilbirnie Loch into which is 35km in length from its source south of Eaglesham to where it joins the Clyde Estuary at Renfrew. Castle Semple Loch. To preserve some of the marshy habitat in the There are also a number of tributaries that feed these rivers such as the Levern Water, Kittoch Water, Earn area, the Dubbs Water, which drains from Kilbirnie Loch, is channelled Water, Green Water, Dargavel Burn and Locher Water and some smaller watercourses such as the Spango around the outside of the Barr Loch. There is an opportunity to manage Burn. There is also a series of burns flowing down from the Clyde Muirshiel plateau. Land use in the area the area as seasonally flooded wetland (3 Lochs Project). To alleviate varies greatly - there is forest, moorland, agriculture, towns, villages, industrial areas, motorways and parks flooding in the vicinity of Calder Bridge, Lochwinnoch, excavation has amongst others, and each type of land use presents different problems and challenges for biodiversity and recently been carried out. -

PPF 2017 MASTER.Pmd

WEST DUNBARTONSHIRE Planning and Perfomance Framework Planning and Building Standards Service July 2017 Planning Performance Framework Foreword This is the sixth reporting year of the an exciting opportunity for the service to be Dumbarton waterfront is also progressing Planning Performance Framework which in the heart of Council services and to work with three out of the four sites having outlines our performance and showcases in a modern purpose built Council office submitted detailed applications for our achievements and improvements in with A listed façade. The new Council development. 2016-17. It also outlines our service office is due to be opened on January Progress of these key development sites improvements for 2017-18. 2018. It will be good to occupy a building has put increased pressure on the service which our service has had a major influence Last year’s Planning Performance as we try to support the development of on its design. Framework was peer reviewed by Glasgow these sites with the same resources as City Council who are part of our Solace As this is the sixth Planning Performance before. The Service has been successful Benchmarking Group. This exercise was Framework I took the opportunity to revisit this year in securing the funding for a part- very useful with good feedback being our first Planning Performance Framework time Planning Compliance Officer and the received. This has helped to shape the back in September 2012. It was good to Strategic Lead of Regeneration has agreed format and content of this year’s Planning see how much progress has been made in to fund a Lead Planning Officer post for 2 Performance Framework. -

Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Clyde and Loch Lomond

Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan June 2016 Published by: Glasgow City Council Delivering sustainable flood risk management is important for Scotland’s continued economic success and well-being. It is essential that we avoid and reduce the risk of flooding, and prepare and protect ourselves and our communities. This is first local flood risk management plan for the Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District, describing the actions which will make a real difference to managing the risk of flooding and recovering from any future flood events. The task now for us – local authorities, Scottish Water, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), the Scottish Government and all other responsible authorities and public bodies – is to turn our plan into action. Pagei Foreword Theimpactsoffloodingexperiencedbyindividuals,communitiesandbusinessescanbedevastating andlonglasting.Itisvitalthatwecontinuetoreducetheriskofanysuchfutureeventsandimprove Scotland’sabilitytomanageandrecoverfromanyeventswhichdooccur. ThepublicationofthisPlanisanimportantmilestoneinimplementingtheFloodRiskManagement (Scotland)Act2009andimprovinghowwecopewithandmanagefloodsintheClydeandLoch LomondLocalPlanDistrict.ThePlantranslatesthislegislationintoactionstoreducethedamageand distresscausedbyfloodingoverthefirstplanningcyclefrom2016to2022.ThisPlanshouldberead inconjunctionwiththeFloodRiskManagementStrategythatwaspublishedfortheClydeandLoch LomondareabytheScottishEnvironmentProtectionAgencyinDecember2015. -

Clyde Gateway Green Network Strategy Final Report Prepared For

Clyde Gateway Green Network Strategy Final Report Prepared for the Clyde Gateway Partnership and the Green Network Partnership by Land Use Consultants July 2007 37 Otago Street Glasgow G12 8JJ Tel: 0141 334 9595 Fax: 0141 334 7789 [email protected] CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 1 Clyde Gateway ............................................................................................................................................1 The Green Network ..................................................................................................................................1 The Clyde Gateway Green Network Strategy.....................................................................................3 2. Clyde Gateway Green Network Policy Context.............................. 5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................................5 Background to the Clyde Gateway Regeneration Initiative ..............................................................5 Regional Policy.............................................................................................................................................8 Local Policy.................................................................................................................................................10 Conclusions................................................................................................................................................17 -

National Developments – Response Form

Planning for Scotland in 2050 National Planning Framework 4 National Developments – Response Form Please use the table below to let us know about projects you think may be suitable for national development status. You can also tell us your views on the existing national developments in National Planning Framework 3, referencing their name and number, and providing reasons as to why they should maintain their status. Please use a separate table for each project or development. Please fill in a Respondent Information Form and return it with this form to [email protected]. Name of proposed Shawfield National Business District Remediation national development Brief description of To complete the remediation strategy of the 63 acre proposed national site at Shawfield addressing the historic Chromium development contamination and thereby removing the health dangers and improving the water quality of the River Clyde. Only a comprehensive strategy and concerted effort with Government and stakeholders including Scottish Environmental Protection Agency, South Lanarkshire Council and Glasgow City Council will achieve this and deliver the economic outputs and associated employment opportunities. Location of proposed G73, Shawfield, Rutherglen/Glasgow. national development (information in a GIS format is welcome if available) What part or parts of the A PPP consent is in place for the masterplan site development requires (Phases 1, 2 and 3), an MSC development for Phase planning permission or 1 has completed and detailed consent is required for other consent? key remediation activity and future land uses. When would the Shawfield Phase 1 is already development ready and development be complete has seen the successful delivery of a £9.2m business or operational? centre (Red Tree Magenta) which was fully let within 10 weeks. -

Environment Baseline Report Scottish Sustainable Marine Environment Initiative

State of the Clyde Environment Baseline Report Scottish Sustainable Marine Environment Initiative SSMEI Clyde Pilot State of the Clyde Environment Baseline Report March 2009 D Ross K Thompson J E Donnelly Contents 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................1 2 THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT..............................................................................3 2.1 GEOLOGY....................................................................................................................3 2.2 THE SEALOCHS ...........................................................................................................6 2.3 THE ESTUARIES ..........................................................................................................9 2.4 THE INNER FIRTH......................................................................................................12 2.5 THE OUTER FIRTH ....................................................................................................14 2.6 COASTAL FLOODING .................................................................................................18 3 CLEAN AND SAFE SEAS............................................................................................19 3.1 THE CHEMICAL ENVIRONMENT ................................................................................19 3.1.1 Dissolved Oxygen.............................................................................................19 3.1.2 Nutrients...........................................................................................................22 -

Carbon Dioxide and Methane Temporal Dynamics in an Urban River

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-5987, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Carbon dioxide and methane temporal dynamics in an urban river Chao Gu, Adrian Bass, and Susan Waldron University of Glasgow, College of Science and Engineering, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, United Kingdom ([email protected]) Rivers are a significant conduit for carbon (C) transport and transformation. Most rivers are a source of carbon to the atmosphere as either carbon dioxide (CO2) or methane (CH4) with greenhouse gas emissions from fluvial systems accounting for a significant proportion of annual global emissions. It is crucial to identify the sources and controls of fluvial CO2 and CH4emissions as climate induced hydrological change continues. The River Kelvin flows through several different land use types (e.g., hills, grassland, pasture, forest, urban centers), draining an area of roughly 352 km2. Variable land use types make the Kelvin River catchment an ideal natural laboratory to understand land use controls on fluvial carbon transport. Weekly sampling is being undertaken at Kelvingrove Park in the catchment’s urban center, where close (1.2 km) to the River Clyde Estuary, discharging a terrestrial C load into the marine environment. So far we understand that 1) the mean concentration of dissolved 13 CO2 ([CO2*]) at the study site was 47.26 ± 14.76 µM while the mean δ CO2 was -17.96 ± 4.03 , the mean 13 dissolved CH4 ([CH4]) was 4.01 ± 1.91 µM while the mean δ CH4 was -48.81 ± 7.86 -

And Two-Dimensional Model Simulation of the Clyde Estuary, Glasgow

The 7th Int. Conf. on Hydroscience and Engineering (ICHE-2006),Sep 10 –Sep 13,Philadelphia,USA 1 A COMPARISON OF ONE- AND TWO-DIMENSIONAL MODEL SIMULATION OF THE CLYDE ESTUARY, GLASGOW Damir Bekic1, David Alan Ervine2 and Pascal Lardet3 ABSTRACT This paper evaluates one- and two-dimensional numerical models for the simulation of estuary hydrodynamics, in this case for the Clyde Estuary, Glasgow. The evaluation is based on identification of the relative strength and limitations of two commercial numerical models, namely ISIS 1-d and MIKE21. The estuary dynamic is analysed on meso-scale domain and over a few tidal periods. On such spatial and temporal scale, the water body is under dominant influence of tidal waves and surface runoff, but also affected by wind shear and atmospheric pressure. The Clyde estuary has a meso-tidal range and long-term average river inflow of 110 m3/s. Upstream of the city of Glasgow the estuary is fluvio dominant, but tidally dominant in the city centre and downstream of the city. The upstream reach is meandering in plan, and the downstream reach has a funnel shape of increasing width. Numerical simulations are conducted for several historical events. The relative influence of tides, storm surge, river inflow, precipitation, wind shear and air pressure is analysed. Predictions of water levels by numerical models are inter-compared and also compared to the recordings on several water gauging stations. A sensitivity analysis on the various tidal shapes, fresh water inflows, wind shear and air pressure is conducted. 1. INTRODUCTION Around 1.8 million people, approximately two fifths of Scotland’s population live in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley, with 600,000 living within the city boundaries. -

The Clyde Walkway Is a Partnership Venture Based on 5 Co-Operation and Agreement

Thanks to The Clyde Walkway is a partnership venture based on 5 co-operation and agreement. North Lanarkshire, South Lanarkshire and Glasgow City Councils would like to acknowledge the help and support of the many agencies and organisations involved in its development, management and promotion, including: Scottish Enterprise, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Big Lottery, Sustrans, The Forestry Commission, The Paths for All Partnership, Strathclyde European Partnership, Scottish Power, Scottish Wildlife Trust, VisitScotland, The Glasgow & Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership. We would also like to thank, in particular, the many individual landowners along the route who have given their support and co-operation to the project. The Clyde Walkway Crossford to a Falls of Clyde, w a New Lanark lk th ro s u ll gh fa o e rch th ard country to Produced for Community and Enterprise Resources by Communications and Strategy. 027182/Feb16 The Clyde Route description and features of interest Walkway If you are joining the Clyde Walkway at Crossford village the route starts at the entrance to the Valley International Park visitor and garden centre, access to which Crossford to is on the right-hand side of the B7056 Braidwood Road immediately adjacent to Falls of Clyde, Crossford Bridge . The path follows New Lanark the riverbank through woodland to a suspension footbridge across the river. Alternatively you can gain access to the In short... Clyde Walkway by walking along the Clyde Valley Tourist Route, A72 Lanark From Crossford village in the heart Road, towards Lanark, for approximately of the Clyde valley the Clyde Walkway 500 metres from the centre of the village runs for 8 miles, through orchard country and cross the river at the car park on and spectacular wooded gorges, the left hand side of the road, by way to New Lanark UNESCO World Heritage of Carfin Footbridge .