S Ijfsta REVOLUTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

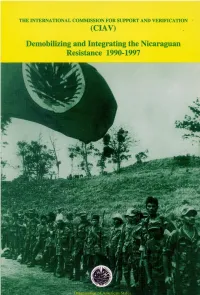

Demobilizing and Integrating the Nicaraguan Resistance 1990-1997

The International Commission for Support and Verification Commission (CIAV) Demobilizing and Integrating the Nicaraguan Resistance 1990-1997 ii Acknowledgements: This paper is a summary English version, written by Fernando Arocena, a consultant to CIAV-OAS, based on the original Spanish report: “La Comisión Internacional de Apoyo y Verificación, La Desmovilización y Reinserción de la Resistencia Nicaragüense 1990 – 1997”, prepared by Héctor Vanolli, Diógenes Ruiz and Arturo Wallace, also consultants to the CIAV-OAS. Bruce Rickerson, Senior Specialist at the UPD revised and edited the English text. This is a publication of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. Correspondence should be directed to the UPD, 1889 "F" Street, N.W., 8th Floor, Washington, DC, 20006, USA. Copyright ©1998 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS................................................................................................................................ix READER'S GUIDE ..................................................................................................................... xi INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................xiii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... -

Abrams Says Resignation of Uno Leader Arturo Cruz Heavy Blow to Contra Movement Deborah Tyroler

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiCen Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 2-13-1987 Abrams Says Resignation Of Uno Leader Arturo Cruz Heavy Blow To Contra Movement Deborah Tyroler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen Recommended Citation Tyroler, Deborah. "Abrams Says Resignation Of Uno Leader Arturo Cruz Heavy Blow To Contra Movement." (1987). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen/432 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiCen by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 077109 ISSN: 1089-1560 Abrams Says Resignation Of Uno Leader Arturo Cruz Heavy Blow To Contra Movement by Deborah Tyroler Category/Department: General Published: Friday, February 13, 1987 At a Feb. 11 meeting with more than 200 top university educators at the State Department, Asst. Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Elliott Abrams said the resignation of Arturo Cruz from the United Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO) would deal a heavy blow to the contra movement. In view of Cruz's reported resignation, Abrams said the contra forces are discussing what constitutes a "better structure, a more effective structure...You must remember that support for the opposition is directly proportional to its effectiveness." At a recent press conference UNO leader Adolfo Calero refused to comment on the resignation -

Nicaraguan Sandinismo, Back from the Dead?

NICARAGUAN SANDINISMO, BACK FROM THE DEAD? An anthropological study of popular participation within the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional by Johannes Wilm Submitted to be examined as part of a PhD degree for the Anthropology Department, 1 Goldsmiths College, University of London 2 Nicaraguan Sandinismo, back from the Dead? An anthropological study of popular participation within the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional I declare that this thesis is entirely my own work and that the thesis presented is the one upon which I expect to be examined. The copyright holders of the included photos/pictures are mentioned in the caption. Usage rights for purposes that go beyond the reproduction of this book either in its entirety or of entire chapters, must be obtained individually from the mentioned copyright holders. When no copyright holder is mentioned in the caption, I was the photographer. The photos taken by me can be used for other purposes without prior consent, as long as the photographer is mentioned in all forms of publication where the photos appear. Johannes Wilm 3 Abstract Thirty years after redefining the political landscape of Nicaragua, Sandinismo is both a unifying discourse and one driven by different interpretations by adherents. This thesis examines the complex legacy of Sandinismo by focusing on the still widely acclaimed notion of Sandinismo as an idiom of popular participation. A central point is the current unity of the movement, as it is perceived by Sandinistas, depends on a limited number of common reference points over the last 100 years of Nicaraguan history, which are interpreted very differently Sandinistas and other groups, but which always emphasise the part Nicaraguans play in international relations and the overall importance of popular mass participation in Nicaraguan politics, rather than agreement on current, day-to-day politics. -

Socialist Register 2005 O Império Reloaded

Socialist Register 2005 O Império Reloaded Editores: Leo Panitch e Colin Leys Sumário Leo Panitch e Colin Leys Prefácio Varda Burstyn A Nova Ordem Imperial Prevista Stephen Gill As Contradições da Supremacia dos EUA Leo Panitch e Sam Gindin As Finanças e o Império Estadunidense Christopher Rude O Papel da Disciplina Financeira na Estratégia Imperial Scott Forsyth Hollywood Reloaded: O Filme como Mercadoria Imperial Vivek Chibber Revivendo o Estado Desenvolvimentista? O Mito da “Burguesia Nacional” Gerard Greenfield Bandung redux: Nacionalismos Antiglobalização no Sudeste Asiático Yuezhi Zhao A Matrix Midiática: A Integração da China no Capitalismo Mundial Patrick Bond O império norte-americano e o subimperialismo sul africano Doug Stokes Terrorismo, Petróleo e Capital: A Contra- insurgência Norte-Americana na Colômbia Paul Cammarck “Sinais dos Tempos”: Capitalismo, Competitividade, e a Nova Face do Império na América Latina Boris Kagarlitsky O Estado Russo na Era do Império Norte- Americano John Grahl A União Européia e o Poder Norte-Americano Tonny Benn e Colin Leys Bush e Blair: o Iraque e o Vice-Rei Norte- Americano da Grã-Bretanha PREFÁCIO Este volume, o da 41ª Socialist Register anual, é o que acompanha o extremamente bem-sucedido volume de 2004 sobre O Novo Desafio Imperial. Planejado originalmente como um volume único que logo se mostrou demasiado grande, formam agora um par que se complementa. O Novo Desafio Imperial lida com a natureza geral da nova ordem imperial –como entender e explicá-la, e quais suas forças e fraquezas. O Império Reloaded circunda-o com uma análise das finanças, da cultura e do modo com que o novo imperialismo está penetrando nas maiores regiões do mundo –Ásia Menor, Sudeste Asiático, Índia, China, África, América Latina, Rússia e Europa. -

Mengapa Tidak!

Vol. 4 No. 1 Oktober - Desember 2008 Belajar dari Sosialisme Baru Amerika Latin: INDONESIA BARU Mengapa Tidak! Daftar Isi Editorial Jalan “Sosialisme Baru” Amerika Latin: Sebuah Era Baru [4] Laporan Utama Transkrip Diskusi Jalan “Sosialisme Baru” Amerika Latin: Dewan Redaksi Sebuah Era Baru [9] Ketua : Amir Effendi Siregar Wakil Ketua : Ivan Hadar Laporan Utama Anggota : Faisal Basri Mian Manurung Jalan “Sosialisme Baru” Amerika Latin: Mungkinkan untuk Nur Iman Subono Indonesia? [32] Arie Sujito Artikel Pelaksana Redaksi Nur Imam Subono: Di balik Kemenangan Evo Morales dan Koordinator : Azman Fajar MAS di Bolivia [37] Redaksi : Puji Riyanto Launa Artikel Nur Imam Subono: Keterkaitan Gerakan Penduduk Asli Alamat Redaksi (Indigenous Movements) dan Kekuatan ”Kiri” (Left) di Jl. Kemang Selatan II No.2A Amerika Latin [43] Jakarta 12730 Telp. 021 -719 3711 (hunting) Artikel Fax. 021 - 7179 1358 Ivan A Hadar: BELAJAR DARI ARGENTINA [48] Jl. Mampang Prapatan XIX No.34 Mampang - Jakarta Selatan Profil Telp/Fax. 021 - 798 4559 Sritua Arief: BIOGRAFI DAN PEMIKIRAN DEPENDENSI DI INDONESIA [51] Ilustrasi* Kuss Indarto Serial Sejarah Sosdem Danan Arditya PLURALITAS KELOMPOK KIRI AMERIKA LATIN [54] Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Serial Sejarah Sosdem Penerbit SEJARAH SOSDEM [56] Pergerakan Indonesia dan Komite Persiapan Yayasan Indonesia Kita Resensi ISSN: 1978-9084 Kebebasan, Negara, dan Pembangunan di Mata Arief Budiman [61] *) Dilarang mengkopi dan memperbanyak ilustrasi tanpa seijin Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Editorial Jalan The Latin America’s “Sosialisme Baru” “New Socialism” Amerika Latin: Way: Sebuah Era Baru A New Era “Bila kita hendak mengentaskan kemiskinan, “When we are about to eliminate kita harus berikan kekuasaan, pengetahuan, poverty, we must give power, tanah, kredit, teknologi, dan organisasi pada si knowledge, land, credit, technology, miskin” and organization to the poor” Hugo Chavez, 2005 Hugo Chavez, 2005 Another Latin America is Possible. -

Culture and Arts in Post Revolutionary Nicaragua: the Chamorro Years (1990-1996)

Culture and Arts in Post Revolutionary Nicaragua: The Chamorro Years (1990-1996) A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Tatiana Argüello Vargas August 2010 © 2010 Tatiana Argüello Vargas. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Culture and Arts in Post Revolutionary Nicaragua: The Chamorro Years (1990-1996) by TATIANA ARGÜELLO VARGAS has been approved for the Center for International Studies by Patrick Barr-Melej Associate Professor of History José A. Delgado Director, Latin American Studies Daniel Weiner Executive Director, Center for International Studies 3 ABSTRACT ARGÜELLO VARGAS, TATIANA, M.A., August 2010, Latin American Studies Culture and Arts in Post Revolutionary Nicaragua: The Chamorro Years (1990-1996) (100 pp.) Director of Thesis: Patrick Barr-Melej This thesis explores the role of culture in post-revolutionary Nicaragua during the administration of Violeta Barrios de Chamorro (1990-1996). In particular, this research analyzes the negotiation and redefinition of culture between Nicaragua’s revolutionary past and its neoliberal present. In order to expose what aspects of the cultural project survived and what new manifestations appear, this thesis examines the followings elements: 1) the cultural policy and institutional apparatus created by the government of President Chamorro; 2) the effects and consequences that this cultural policy produced in the country through the battle between revolutionary and post-revolutionary cultural symbols in Managua as a urban space; and 3), the role and evolution of Managua’s mayor and future president Arnoldo Alemán as an important actor redefining culture in the 1990s. -

Twentieth Century Nicaraguan Protest Poetry: the Struggle for Cultural Hegemony

KU ScholarWorks | The University of Kansas Central American Theses and Dissertations Collection http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Twentieth Century Nicaraguan Protest Poetry: The Struggle for Cultural Hegemony by Kenneth R. Kincaid M.A., University of Kansas, 1994 Professor in Charge Charles Stansifer Committee Members Vicky Unruh Elizabeth Kuznesof The University of Kansas has long historical connections with Central America and the many Central Americans who have earned graduate degrees at KU. This work is part of the Central American Theses and Dissertations collection in KU ScholarWorks and is being made freely available with permission of the author through the efforts of Professor Emeritus Charles Stansifer of the History department and the staff of the Scholarly Communications program at the University of Kansas Libraries’ Center for Digital Scholarship. TWENTETH CENTURY NiCAR AGUAN PROTEST POETRY: THE STRUGGLE FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY ay * KitK>*fl) TWENTIETH CENTURY NIGARAGUAN PROTEST POETRY: THE STRUGGLE FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY by Kenneth R. ^ncaid M.A., University of' Kansas, 1994 Submitted to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in par• tial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Latin American History. / Charles Stansifer \j \ - : Vic^y Unruh Elizabeth Kuznesof For the Graduate Division Date thesis accepted RGOSST fifiMflS 5 Abstract The 1979 Nicaraguan revolution spawned many demo• cratic reforms. These included agrarian, political, economic and cultural changes that were implemented in order to increase participation in all aspects of Nicara• guan life. Of the changes, one would have to consider those effecting culture and poetry to be the most unique. -

Presidential Elections in Latin America: the Ascent of the Left

Presidential Elections in Latin America: The Ascent of the Left PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS IN LATIN AMERICA: THE ASCENT OF THE LEFT IGNACIO MEDINA NÚÑEZ Colección Insumisos Latinoamericanos elaleph.com Medina Núnez, Ignacio Presidential elections in Latin America: the ascent of the left. - 1a ed. - Buenos Aires: Elaleph.com, 2013. 280 p.; 21x15 cm. - (Insumisos latinoamericanos) ISBN 978-987-1701-58-2 1. Ciencias Políticas. I. Título CDD 320 Queda rigurosamente prohibida, sin la autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright, bajo las sanciones establecidas por las leyes, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, comprendidos la fotocopia y el tratamiento informático. This book was published in Spanish. This English translation is a revised and augmented version. Original Title: Elecciones presidenciales en América Latina. El ascenso de una izquierda heterogénea. Author: Ignacio Medina Núñez Pages: 354, ISBN: 978-987-1070-89-3 Year: 2009 Elaleph. Buenos Aires, Argentina. © 2013, Ignacio Medina Núñez. © 2013, Elaleph.com S.R.L. [email protected] http://www.elaleph.com Primera edición Este libro ha sido editado en Argentina. ISBN 978-987-1701-58-2 Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723 Impreso en el mes de marzo de 2013 en Bibliográfi ka, Bucarelli 1160, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Insumisos Latinoamericanos Cuerpo Académico Internacional e Interinstitucional Director Robinson Salazar Pérez Cuerpo académico y Comité editorial Pablo González Casanova, Jorge Alonso Sánchez, Jorge Beinstein, Fernando Mires, Manuel A. Garretón, Martín Shaw, Jorge Rojas Hernández, Gerónimo de Sierra, Alberto Riella, Guido Galafassi, Atilio A. Boron, Roberto Follari, Ambrosio Velasco Gómez, Oscar Picardo Joao, Carmen Beatriz Fernández, Edgardo Ovidio Garbulsky, Héctor Díaz-Polanco, Rosario Espinal, Sergio Salinas, Alfredo Falero, Álvaro Márquez Fernández, Ignacio Medina, Marco A. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Modern Languages Constructing a Nation: Evaluating the Discursive Creation of National Community under the FSLN Government in Nicaragua (1979-1990) by Lisa Marie Carroll-Davis Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Modern Languages Doctor of Philosophy CONSTRUCTING A NATION: EVALUATING THE DISCURSIVE CREATION OF NATIONAL COMMUNITY UNDER THE FSLN GOVERNMENT IN NICARAGUA (1979-1990) by Lisa Marie Carroll-Davis This thesis aims to examine the ways in which national identity can be discursively created within a state. I consider the case of Nicaragua in the 1980s and investigate how the government of the Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN) established a conception of the national in the country through official discourse. -

The Ends of Modernization: Development, Ideology, and Catastrophe in Nicaragua After the Alliance for Progress

THE ENDS OF MODERNIZATION: DEVELOPMENT, IDEOLOGY, AND CATASTROPHE IN NICARAGUA AFTER THE ALLIANCE FOR PROGRESS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by David Johnson Lee December 2015 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Richard Immerman, Advisory Chair, History, Temple University Dr. Harvey Neptune, History, Temple University Dr. David Farber, History, University of Kansas Dr. Michel Gobat, History, University of Iowa © Copyright 2015 by David Johnson Lee All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the cultural and intellectual history of Nicaragua from the heyday of modernization as ideology and practice in the 1960s, when U.S. planners and politicians identified Nicaragua as a test case for the Alliance for Progress, to the triumph of neoliberalism in the 1990s. The modernization paradigm, implemented through collusion between authoritarian dictatorship and the U.S. development apparatus, began to fragment following the earthquake that destroyed Managua in 1972. The ideas that constituted this paradigm were repurposed by actors in Nicaragua and used to challenge the dominant power of the U.S. government, and also to structure political competition within Nicaragua. Using interviews, new archival material, memoirs, novels, plays, and newspapers in the United States and Nicaragua, I trace the way political actors used ideas about development to make and unmake alliances within Nicaragua, bringing about first the Sandinista Revolution, then the Contra War, and finally the neoliberal government that took power in 1990. I argue that because of both a changing international intellectual climate and resistance on the part of the people of Nicaragua, new ideas about development emphasizing human rights, pluralism, entrepreneurialism, indigenous rights, and sustainable development came to supplant modernization theory. -

UN Digital Library

UNITED *-7’; NATIONS q -c L S PROVISIONAL S/PV.2792 17 February 1988 ENGLISH PROVISIONAL VERBATIM RECORD OF THE TWO THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND NINETY-SECOND MEETING Held at Headcuarters, New York, on Wednesday, 17 February 1988, at 10.30 a.m. President: Mr. WALTERS (United States of America) Members: Algeria Mr. ACHACHE Argentina Mr. DELPECH Brazil Mr. ALLENCAR China Mr. LI LUye France Mr. BLANC -_ -Germany, Federal Republic of Mr. VERGAU Italy Mr. BUCCI Japan Mr. KAGAMI Nepal Mr. RANA Senegal Mr. SARRE Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Mr. BELONOGOV United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Mr. BIRCH Yugoslavia Mr. PEJIC Zambia Mr. ZUZE This record contains the original text of speeches delivered in English and interpretations of speeches in the other languages. The'final~text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to original speeches only. They should be &R?:nx~u&&r the signature of a member of the delegation concerned, within one week, to the Chief, Official Records Editing Section, Department of Conference Services, tbbm DC&750, 2 United Nations Plaza, and incorporated in a copy of the record. 88-6U286A 3286V (E) 2-d . 3 ..'. RW3 S/PV.2792 &&pi 2-5 The meeting was called to order a-t lo,55 a..m. ADOP.l!IONOF TBE AGENDA The agenda was adopted. LETTER DATED 18FEBRUARY 1988 FRa TBE PERMANENTOBSERVER OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA TD THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED 'ID THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY CXINCIL (s/19488) =m DATED 18 FEBRUARY 1988 FRW THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF JAPAN 'IO THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED IO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY CDUNCIL (S/19489) The PRESIDENT: In accordance with decisions taken by the Council at its 2791st meeting, I invite the representative of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the \ representative of the Republic of Korea to take places at the Council table. -

Derian, Patricia

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PATRICIA DERIAN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 12, 1996 Copyright 2 14 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in New York City$ raised in Washington, DC, Virginia and California. Life in segregated Danville, VA Palos Verdes College$ University of Virginia ,arriage Husband.s medical practice/ various locations in U.S. Birth of sons 0ecruitment of nurses 1ackson, ,ississippi/ Accompanying husband c1234 Segregation environment ,ississippians for Public Education ,edgar Evers assassination Participation in civil rights movement Foreign travel 6p218 Early political activity 6,ississippi8 c1273-1277 1234 Democratic Party Convention ,ississippi delegation National Committeewoman Democratic Party of the State of ,ississippi ; 1immy Carter meeting Democratic Policy Council Averell Harriman Laos and Cambodia resolution Southern 0egional Council Henry Wallace Deputy Director, 1immy Carter campaign staff 612738 ACLU Committee member State Department job offer ,ississippi political and social environment 1 1oan Braden State Department/ Coordinator/ Assistant Secretary for Human 1277-1283 0ights and Humanitarian Affairs History and personnel of office ,ark Schneider 0oberta Cohen Stephen Cohen Security process Amnesty International yearbook Christopher interview Congressman Donald Fraser Establishing bureau Dealing with bureaucracy ,ember, Committee on Security and Cooperation in Europe 6CSCE8 Controversy Argentina visit$ meetings