Demobilizing and Integrating the Nicaraguan Resistance 1990-1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

República De Nicaragua

000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 670 680 690 700 710 720 730 740 750 760 770 Podriwas 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 5 5 1 1 Biltignia y REPa ÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA ka Kukalaya c a o m MINISTERIOB DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAEASTRUCTURA Planta El Salto WW ii ww ii ll íí dd ee DIVISIÓN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN JJ ii nn oo tt ee gg aa Elefante Blanco is MAPA MUNICIPAL DE SIUNA P La Panama is P BONANZA RED VIAL INVENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE Plan Grande ¤£414 Río Sucio y a BB oo nn aa nn zz aa c (Amaka) 0 o a 0 0 o 0 0 B in 0 0 W 0 5 5 5 5 1 Murcielago 1 Mukuswas Ojochal Minesota El Naranjal Lugar Tablazo Kalangsa Españolina a k a m A Los Placeres SS aa nn JJ oo ss éé El Cacao B o dd ee BB oo cc aa yy ca y y a c o B El Cocal Wihilwas 0 0 0 0 0 Bam 0 ba 0 n 0 a 4 Fruta de Pan 4 5 y 5 a 1 1 c Kalmata o B Lugar Kalmata San Pablo Lugar Betania y El Salto El Ojochal a c o B B o c a y B o R o s i t a c R o s i t a a U y li 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 El Dos 0 3 3 5 W Sipulwas San Antonio 5 B 1 a 1 o n de Banacruz c i a y Loma El Banasuna Divisadero Las Delicias El Consuelo Yakalwas Cerro Las Américas Ayapal La Florida Ayapal El Carao Turuwasitu ¤£277 Talavera Ulí Turuwas Abajo San Martin El Edén Los Blandones Pueblo Amado F. -

Caracterizacion Socio Economica De La Raan

Fundación para el Desarrollo Tecnológico Agropecuario y Forestal de Nicaragua (FUNICA) Fundaci ón Ford Gobierno Regional de la RAAN Caracterización socioeconómica de la Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte (RAAN) de Nicaragua ACERCANDO AL DESARROLLO Fundación para el Desarollo Tecnológico Agropecuario y Forestal de Nicaragua (FUNICA) Fundación Ford – Gobierno Regional Elaborado por: Suyapa Ortega Thomas Consultora Revisado por: Ing. Danilo Saavedra Gerente de Operaciones de FUNICA Julio de 2009 Caracterización Socioeconómica de la RAAN 2 Fundación para el Desarollo Tecnológico Agropecuario y Forestal de Nicaragua (FUNICA) Fundación Ford – Gobierno Regional Índice de contenido Presentacion ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Perfil general de la RAAN .............................................................................................. 7 II. Entorno regional y demografía de la RAAN.................................................................... 8 III. Organización territorial ................................................................................................ 11 3.1 Avance del proceso de demarcación y titulación .................................................... 11 IV. Caracterización de la RAAN ....................................................................................... 13 4.1 Las características hidrográficas .......................................................................... 13 Lagunas....................................................................................................................... -

REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA 1 Biltignia ¤£ U Kukalaya K Wakaban a Sahsa Sumubila El Naranjal Lugar Karabila L A

000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 740 750 760 770 780 790 800 810 820 830 840 850 860 870 880 Lugar Paso W a s p á m Mina Columbus Cuarenta y Tres El Paraiso Wawabun UKALAYA awa Llano Krasa K La Piedra San Miguel W La Unión Tingni 0 487 0 0 Podriwas Mani Watla 0 0 ¤£ Empalme de 0 0 Grey Town La PAlmera 0 6 Sukat Pin 6 5 5 K 451 Santa Rosa 1 REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA 1 Biltignia ¤£ U Kukalaya K Wakaban A Sahsa Sumubila El Naranjal Lugar Karabila L A Y MINISTERIOP laDnta EEl Sa ltoTRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA A Leimus Dakban Risco de Oro Yulu Dakban DIEVlefaIntSe BIlaÓncoN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN Lawa Place Î La Panama Risco de Oro Kukalaya Cerro Krau Krau BONANZA B o n a n z a MAPA MUNRíIo CSucIioPAPLlan GDrandEe PRINZAPOLKA ¤£423 Rio Kukalaya W a w 414 (Amaka) Las Breñas a s ¤£ i 0 0 0 0 0 P Santa Clara 0 0 REs D VIAL INVENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE 0 i P loma La 5 5 5 Murcielago Esmeralda La Potranca (Rio Sukat Pin 5 1 Industria 1 Ojochal Mukuswas Minesota Susun Arriba Kuliwas 410 Maderera o El Naranjal ¤£ A Sirpi) Y Wasminona La Luna A Españolina L A Klingna El Doce Lugar La K Susun U Potranca K El Cacao Los Placeres ¤£397 Kuliwas P u e rr tt o Klingna Landing El Corozo Empalme de C a b e z a s Wasminona ROSITA Î Karata Wihilwas El Cocal Cerro Liwatakan 0 Muelle 0 0 Bambanita 0 0 0 O 0 Cañuela Comunal 0 k 4 Buena Vista o 4 n 5 Kalmata Rio Bambana w 5 1 a 1 s Fruta de Pan La Cuesta Bambana Lugar Kalmata San Pablo de Alen B am R o s ii tt a KUKA Lapan b L a A n Y Î Omizuwas a A El Salto Lugar Betania Muelle Comunal Sulivan Wasa King Wawa Bar Cerro Wingku Waspuk Pruka 0 Lugar Kawibila 0 0 0 0 Cerro Wistiting 0 0 El Dos 0 3 San Antonio 3 5 de Banacruz 5 1 Banacruz 1 K UK A L Rio Banacruz A UKALA Y K YA Las Delicias A Banasuna Cerro Las El Sombrero Américas Pauta Bran L a El Carao y La Florida a s i Talavera k B s a Ulí am F. -

Baseline Study Report

Baseline Study Report MESA II Project - Better Education and Health Agreement: FFE-524-2017/025-00 Final Evaluation Report Coordinated by Project Concern International (PCI) Nicaragua August/Sept. 2017 Submitted to USDA/FAS Project “Mejor Educación y Salud (MESA)” - Nicaragua Agreement: FFE-524-2013-042-00 Submitted to: USDA/FAS Vanessa Castro, José Ramón Laguna, Patricia Callejas with collaboration from Micaela Gómez Managua, December 2017 June 4, 2019 Managua, Nicaragua i Acknowledgements The consultant team appreciates PCI Nicaragua for entrusting Asociación Nicaragua Lee with the completion of this study. In particular, we would like to acknowledge the valuable support provided by María Ángeles Argüello and María Zepeda at PCI Nicaragua-, and by officials from the Ministry of Education (MINED) in Managua and in the departmental delegations of Jinotega and the Southern Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCS). We also recognize the support given by the officials at the MINED offices in the 11 municipalities participating in the study: Jinotega, La Concordia, San Sebastian de Yali, Santa Maria de Pantasma, Bluefields, Kukra Hill, La Cruz del Río Grande, Laguna de Perlas, Desembocadura Río Grande, El Tortuguero and Corn Island. In particular, we would like to acknowledge the enthusiasm showed by the educational advisors from the aforementioned MINED municipal offices, in the administration of the instruments Our greatest gratitude and consideration to the actors of this study, the fourth-grade students from the elementary schools included in the sample, who agreed and participated with great enthusiasm. We would also like to thank the third-grade teachers who contributed by answering the questionnaire. We should also mention and thank the team of supervisors, applicators and data entry personnel, who put much dedication and effort into the collection and processing of the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) instruments, the questionnaires, and the school and classroom environment observation sheet. -

Chapter 16 Road Sector Development Plan 16.1 Road Network

Nicaragua National Transportation Plan Final Report Chapter 16 Road Sector Development Plan 16.1 Road Network Improvement Plan 16.1.1 Introduction As mentioned in Chapter 13.5, the main policies of the transport sector in the National Transport Plan is to develop a transport network system to support economic growth, assist social activities so as to decrease regional disparities, and to develop infrastructure resilient to the impact of climate change. This chapter discusses the various measures to realize the policies established. 16.1.2 Planning Methodology Figure 16.1.1 illustrates the planning process of the road network development plan. The development projects or the candidate projects that will contribute in improving the existing road network will be selected by integrating the projects that are being implemented or are on the course of planning by MTI with the proposed improvement works to improve the present road network. Present Road Network On-going and Planned Projects Planning Concept Proposed Improvement Works Proposed Road Network Development Projects (Candidate Projects) Figure 16.1.1 Planning Process of Road Network Development Plan Source: JICA Study Team 16.1.3 Present Road Network Although, the total road network in Nicaragua totals to 23,647km, only the basic road network under the jurisdiction of MTI, which totals to approximately 8,517 km (trunk road and collector road) will be targeted for road network development plan. 16.1.4 Integration of On-going and Planned Projects On-going projects and planned projects for fiscal year 2014-2016 were identified and those that needed to be included in the NTP were selected. -

6-Months Operation Update Central America: Hurricanes Eta & Iota

6-months Operation Update Central America: Hurricanes Eta & Iota Glide N°: TC-2020-000218-NIC Emergency Appeal N° MDR43007 TC-2020-000220-HND TC-2020-000222-GTM Operation update N° 3 Period covered by this update: 8 November 2020 Date of issue: 22 June 2021 to 15 May 2021 Timeframe: 18 months Operation start date: 8 November 2020 End date: 31 May 2022 Funding requirement (CHF): CHF 20 million As of 31 May 2021, 71 per cent of the Appeal has been covered. The IFRC kindly encourages increased donor support for this Emergency Appeal to enable host National Societies to continue to provide DREF initially allocated: CHF 1 million support to the people affected by Hurricanes Eta and Iota, primarily in the process of recovering their livelihoods, which were almost entirely devastated. Click here for the donor response. Number of people to be assisted: 102,500 people (20,500 families) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: American Red Cross, British Red Cross, French Red Cross, German Red Cross, Guatemalan Red Cross, Honduran Red Cross, Italian Red Cross, Nicaraguan Red Cross, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Norwegian Red Cross, Spanish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross and Canadian Red Cross Society. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Guatemala: National Disaster Reduction Coordination (CONRED); Honduras: National Risk Management System (SINAGER); Nicaragua: National System for Disaster Prevention, Mitigation and Care (SINAPRED); Regional Group on Risks, Emergencies and Disasters for Latin America and the Caribbean (REDLAC), Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), United Nations System agencies and programmes and Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) member organizations. -

Nicaraguan Defense Ministry Reports on Recent Casualties Deborah Tyroler

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiCen Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 8-23-1989 Nicaraguan Defense Ministry Reports On Recent Casualties Deborah Tyroler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen Recommended Citation Tyroler, Deborah. "Nicaraguan Defense Ministry Reports On Recent Casualties." (1989). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen/ 3308 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiCen by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 072238 ISSN: 1089-1560 Nicaraguan Defense Ministry Reports On Recent Casualties by Deborah Tyroler Category/Department: General Published: Wednesday, August 23, 1989 According to a Defense Ministry statement released late Aug. 20, a contra unit ambushed an army truck on the Acoyapalas Animas highway, Magnolia, Chontales department on the evening of Aug. 19. Among civil guards and reservists traveling in the truck, two were killed and six wounded. Also on Aug. 19, contras ambushed government soldiers in the Los Gatos area, 20 km. southeast of Acoyapa. One soldier was injured. The Ministry reported that two contras were killed in both clashes, including a commander known as "Mechudo." According to a communique by the Defense Ministry released Aug. 22, clashes between contra units and government troops on Sunday resulted in at least eight dead and two wounded during five separate clashes. Two contras died, including a commander known as Cusuco, in an attack against an army patrol near the village of Santo Domingo, Chontales department, 130 km. -

Nicaragua Strategic Alliances for Social Investment Alliances2 Para La Educación Y La Salud Systematization Report

Nicaragua Strategic Alliances for Social Investment Alliances2 para la Educación y la Salud Systematization Report February 28, 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by RTI International. Nicaragua/Strategic Alliances for Social Investment Alliances2 para la Educación y la Salud Systematization Report Cooperative Agreement 520-A-00-10-00031-00 Prepared for Alicia Slate, AOR U.S. Agency for International Development/Nicaragua Prepared by RTI International 3040 Cornwallis Road Post Office Box 12194 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 RTI International is one of the world's leading research institutes, dedicated to improving the human condition by turning knowledge into practice. Our staff of more than 3,700 provides research and technical services to governments and businesses in more than 75 countries in the areas of health and pharmaceuticals, education and training, surveys and statistics, advanced technology, international development, economic and social policy, energy and the environment, and laboratory testing and chemical analysis. RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government (USG). Table of Contents Page Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ -

Nicaragua Expansion and Strengthening Of

PUBLIC SIMULTANEOUS DISCLOSURE DOCUMENT OF THE INTER-AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK NICARAGUA EXPANSION AND STRENGTHENING OF NICARAGUA’S ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION SYSTEM (NI-L1091) LOAN PROPOSAL This document was prepared by the project team consisting of: Héctor Baldivieso (ENE/CNI), Project Team Leader; Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho (INE/ENE), Project Team Co-leader; Alberto Levy (INE/ENE); Carlos Trujillo (INE/ENE); Carlos Hinestrosa (INE/ENE); Stephanie Suber (INE/ENE); Juan Carlos Lazo (FMP/CNI); Santiago Castillo (FMP/CNI); María Cristina Landázuri (LEG/SGO); Denis Corrales (VPS/ESG); and Alma Reyna Selva (CID/CNI). This document is being released to the public and distributed to the Bank’s Board of Executive Directors simultaneously. This document has not been approved by the Board. Should the Board approve the document with amendments, a revised version will be made available to the public, thus superseding and replacing the original version. CONTENTS PROJECT SUMMARY I. DESCRIPTION AND RESULTS MONITORING ................................................................ 1 A. Background, problem to be addressed, and rationale ................................... 1 B. Objectives, components, and cost ................................................................ 8 C. Key results indicators ................................................................................. 10 II. FINANCING STRUCTURE AND MAIN RISKS ............................................................... 10 A. Financing instruments ............................................................................... -

UN Digital Library

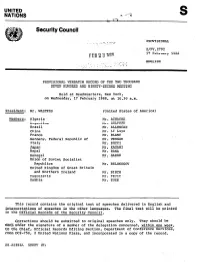

UNITED *-7’; NATIONS q -c L S PROVISIONAL S/PV.2792 17 February 1988 ENGLISH PROVISIONAL VERBATIM RECORD OF THE TWO THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND NINETY-SECOND MEETING Held at Headcuarters, New York, on Wednesday, 17 February 1988, at 10.30 a.m. President: Mr. WALTERS (United States of America) Members: Algeria Mr. ACHACHE Argentina Mr. DELPECH Brazil Mr. ALLENCAR China Mr. LI LUye France Mr. BLANC -_ -Germany, Federal Republic of Mr. VERGAU Italy Mr. BUCCI Japan Mr. KAGAMI Nepal Mr. RANA Senegal Mr. SARRE Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Mr. BELONOGOV United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Mr. BIRCH Yugoslavia Mr. PEJIC Zambia Mr. ZUZE This record contains the original text of speeches delivered in English and interpretations of speeches in the other languages. The'final~text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to original speeches only. They should be &R?:nx~u&&r the signature of a member of the delegation concerned, within one week, to the Chief, Official Records Editing Section, Department of Conference Services, tbbm DC&750, 2 United Nations Plaza, and incorporated in a copy of the record. 88-6U286A 3286V (E) 2-d . 3 ..'. RW3 S/PV.2792 &&pi 2-5 The meeting was called to order a-t lo,55 a..m. ADOP.l!IONOF TBE AGENDA The agenda was adopted. LETTER DATED 18FEBRUARY 1988 FRa TBE PERMANENTOBSERVER OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA TD THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED 'ID THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY CXINCIL (s/19488) =m DATED 18 FEBRUARY 1988 FRW THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF JAPAN 'IO THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED IO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY CDUNCIL (S/19489) The PRESIDENT: In accordance with decisions taken by the Council at its 2791st meeting, I invite the representative of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the \ representative of the Republic of Korea to take places at the Council table. -

An Abstract of the Thesis of Kim Glover for the Master Ofarts in World

An Abstract Of The Thesis Of Kim Glover for the Master ofArts in World History presented on April 30, 2003 Title: The Revolutionary Women ofNicaragua Abstract approved:9" A c5~ This thesis contends that women were active participants in the revolutionary events taking place in Nicaragua between the 1960s through the 1990s. I state in this thesis that women made huge contributions and sacrifices on both sides ofthe Nicaraguan civil war in order to take a part in determining the government oftheir country and to develop a better future for themselves and others. The first chapter ofthis thesis will explain the events leading up to the Sandinista Revolution and the participation of women in the revolt. In chapter 2, in addition to a general overview ofwomen's involvement in the Nicaraguan revolution the thesis will also briefly compare it to the women's involvement in the Cuban revolution years earlier. In the next chapter I will also give personal accounts of several women that fought in the Sandinista revolution and ofthose that fought in the Contra counter-revolution. I have tried to include profiles ofwomen from different social classes and ofthose who fought in either support or combat situations. Chapter 4 ofthe thesis explains the Catholic Church's involvement in recruitment and organization of Sandinista and Contra revolutionaries with an emphasis on the Church's impact on women's involvement in the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberaci6n Nacional). Chapter 5 will list and describe the different women's organizations that formed during the Sandinista revolution and after as well as their effects on women's lives in Nicaragua. -

De Sandino Aux Contras Formes Et Pratiques De La Guerre Au Nicaragua

De Sandino aux contras Formes et pratiques de la guerre au Nicaragua Gilles Bataillon De 1978 à 1987, la vie politique nicaraguayenne a été marquée par la prédomi- nance des affrontements armés. Le pays a en effet connu deux guerres civiles. La première opposa de 1978 à juillet 1979 le Front sandiniste de libération nationale (FSLN), le Conseil supérieur de l’entreprise privée (COSEP), le Parti conserva- teur, les sociaux-chrétiens et les communistes, les syndicalistes de toutes obé- diences à Anastasio Somoza Debayle et ses partisans et pris fin avec la défaite du dictateur. La seconde mit aux prises de 1982 à 1987 le nouvel État dominé par les sandinistes à une nébuleuse d’opposants, la Contra, composée de dissidents du sandinisme, d’anciens partisans de Somoza et de l’organisation indienne de la côte Caraïbe. Ces deux guerres se traduisirent par des affrontements particuliè- rement meurtriers entre les groupes armés, mais les populations civiles ne furent jamais à l’abri des cruautés des différents clans combattants, bien au contraire. Chacune de ces guerres civiles vit les parties en présence faire largement appel à l’aide étrangère. Enfin, les motifs religieux furent étroitement imbriqués aux motifs politiques. Deux interprétations de ces guerres ont été avancées. L’une met l’accent sur les facteurs internes, tant sociaux que politiques ; l’autre souligne le rôle décisif des interventions extérieures. La première, à laquelle est associé le nom d’Edelberto Que soient remerciés Jorge Alanı´z Pinell, Antonio Annino et Jean Meyer, dont les suggestions m’ont permis d’améliorer les premières versions de ce texte, fruit d’une recherche conduite au CIDE (Mexico).