Munyagishari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa and the International Criminal Court: Behind the Backlash and Toward Future Solutions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bowdoin College Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Honors Projects Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2017 Africa and the International Criminal Court: Behind the Backlash and Toward Future Solutions Marisa O'Toole Bowdoin College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects Part of the African Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation O'Toole, Marisa, "Africa and the International Criminal Court: Behind the Backlash and Toward Future Solutions" (2017). Honors Projects. 64. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects/64 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AFRICA AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT Behind the Backlash and Toward Future Solutions An Honors Paper for the Department of Government and Legal Studies By Marisa O’Toole Bowdoin College, 2017 ©2017 Marisa O’Toole Introduction Marisa O’Toole Introduction Following the end of World War II, members of international society acknowledged its obligation to address international crimes of mass barbarity. Determined to prevent the recurrence of such atrocities, members took action to create a system of international individual criminal legal accountability. Beginning with the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes trials in 19451 and continuing with the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 19932 and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in 19943, the international community commenced its ad hoc prosecution of individuals for the commission of international crimes. -

Updates from the International Criminal Courts Nicolas M

Human Rights Brief Volume 12 | Issue 2 Article 10 2005 Updates from the International Criminal Courts Nicolas M. Rouleau American University Washington College of Law Annelies Brock American University Washington College of Law Daisy Yu American University Washington College of Law Anne Heindel American University Washington College of Law Mario Cava American University Washington College of Law See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Rouleau, Nicolas M., Annelies Brock, Daisy Yu, Anne Heindel, Mario Cava, and Tejal Jesrani. "Updates from the International Criminal Courts." Human Rights Brief 12, no. 2 (2005): 33-38. This Column is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Nicolas M. Rouleau, Annelies Brock, Daisy Yu, Anne Heindel, Mario Cava, and Tejal Jesrani This column is available in Human Rights Brief: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief/vol12/iss2/10 Rouleau et al.: Updates from the International Criminal Courts UPDATES FROM THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURTS INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL When this requirement is met, the party argu- The Appeals Chamber then examined the FOR RWANDA ing that there has been a miscarriage of justice Prosecution’s contention that the Trial must further establish “that the error was criti- Chamber had committed an error of fact by GEORGES ANDERSON NDERUBUMWE cal to the verdict reached by the Trial failing to find a nexus between the crimes for RUTAGANDA V. -

THE CONTOURS of VIOLENCE: the Interaction Between Perpetrators

7+(&21728562)9,2/(1&( 7KHLQWHUDFWLRQEHWZHHQSHUSHWUDWRUVDQGWHUUDLQLQWKH5ZDQGDQ*HQRFLGH $1'5($*(/,1$6 68%0,77(',13$57,$/)8/),//0(17 2)7+(5(48,5(0(176)257+( '(*5((2)0$67(52)$576,1+,6725< 1,3,66,1*81,9(56,7< 6&+22/2)*5$'8$7(678',(6 1257+%$<217$5,2 $QGUHD*HOLQDV-XO\ $EVWUDFW 7KLVSDSHUH[DPLQHVWKH5ZDQGDJHQRFLGHRILQDQHZOLJKW7KLVSDSHU VHHNVWRXQGHUVWDQGWKHKRZZKHUHDQGZK\RIWKH5ZDQGDJHQRFLGH,WDVNVWKH TXHVWLRQVKRZGLGJHRJUDSK\DQGWHUUDLQLQIOXHQFHWKHJHQRFLGHSURFHVVLQ5ZDQGD" $QGKRZGLGSHUSHWUDWRUVXVHWKHLURZQNQRZOHGJHRIWKHODQGLQFKRRVLQJPDVVDFUH VLWHV"7KLVSDSHUVKRZVWKHZD\VLQZKLFK5ZDQGDெVVZDPSVKLOOVIRUHVWVULYHUVDQG URDGVXVHGWRIXUWKHUWKHNLOOLQJRIWKH7XWVL8VLQJ*,6DQGSORWWLQJWKHPDVVDFUHVLWHV QHZSDWWHUQVHPHUJHGWKDWVKRZWKHPDVVDFUHVLWHVZHUHQRWUDQGRPEXWLQIDFWLQ VXFKSODFHVWKDWZRXOGIXQQHODQGGLUHFWYLFWLPPRYHPHQWWRZDUGVDUHDVRI5ZDQGD WKDWIDYRXUWKHNLOOHUV7KLVSRZHURYHUWHUULWRU\ZDVH[HUFLVHGRQWKHSDUWRIWKH SHUSHWUDWRUVWRPRUHHIILFLHQWO\LGHQWLI\FRQFHQWUDWHDQGH[WHUPLQDWHWKH7XWVL iv $FNQRZOHGJHPHQWV ,ZRXOGOLNHWRILUVWWKDQNP\DGYLVRU6WHYHIRUEHOLHYLQJLQWKLVSDSHUDVZHOODVKLV DGYLFHDQGIRUKLVLQILQLWHSDWLHQFHZLWKPHDQGVWD\LQJLQP\FRUQHUIRUWKHSDVW \HDUV7R+LODU\ZKRZDVDOZD\VDYDLODEOHIRUKHOSDQGDGYLFHH[FHSWIRUWKDWRQHWLPH ,KDGWRSUHVHQWWRWKHILUVW\HDUFODVV7R-HQQDQG6DEULQDIRUFRQVLVWHQWO\DVNLQJKRZ P\ZULWLQJZDVFRPLQJDORQJLWZDVQRWDQQR\LQJDWDOO7RP\IDPLO\ZKRVWLOOKDVQRW UHDGWKLVWKDQNVIRUVD\LQJLWVRXQGVLQWHUHVWLQJ)LQDOO\,ZRXOGOLNHWRJLYHP\VLQFHUHVW RIWKDQNVWR$OEHUWRZLWKRXWZKRPWKLVSURMHFWZRXOGQRWKDYHJRWRIIWKHJURXQG v Table of Contents ,1752'8&7,21 0(7+2'2/2*< +,6725,2*5$3+< *,6 -

Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE Aerial view of Freetown business district PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Thursday, 29 November 2012 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Charles Taylor May Be Freed / The Nation Page 3 International News Former Liberian President Taylor Should be a "Free Man" – Judge / Reuters Pages 4-5 UN Tribunal Acquits Kosovo Ex-PM of War Crimes / Agence France Presse Pages 6-8 ICTR Transfers Another Genocide Case to Rwanda / The New Times Pages 9-10 German Police 'Just Missed' Most Wanted Rwandan Genocide Suspect / Hirondelle News Agency Page 11 ICTY Upholds Serbian Nationalist Leader's Contempt of Court Sentence / RAPSI Page 12 3 The Nation Thursday, 29 November 2012 4 Reuters Tuesday, 27 November 2012 Former Liberian president Taylor should be a "free man" – judge By Sara Webb Former Liberian President Charles Taylor attends his trial at the Special Court for Sierra Leone based in Leidschendam, outside The Hague, May 16, 2012. REUTERS/Evert-Jan Daniels/Pool Justice Malick Sow's criticism of how the trial was conducted and of the final decision-making process are likely to be seized on by Taylor's defence lawyers as part of his appeal. Taylor, 64, was the first head of state convicted by an international court since the trials of Nazis after World War Two. -

ICTR Newsletter

ICTRPublished by the Comm unicationNewsletter Cluster—ERSPS, Immediate Office of the Registrar United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda December 2010/January 2011 UN Establishes Residual Mechanism for Tribunals On 22 December 2010, the United Nations Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations decided, through Resolution 1966 (2010), to establish a single International Residual Mechanism for the two ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals which shall continue the material, territorial, temporal and personal jurisdiction of both the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), respectively, as set out in their Statutes. While no decision has yet been The Security Council voted to adopt resolution 1966 (2010), which establishes the International Residual Mechanism for made as to the location of the Criminal Tribunals to finish the remaining tasks of the Tribunals Mechanism itself, it has however two for Rwanda and the Former Yugoslavia. branches, one branch for the ICTY (right) Rosemary A. DiCarlo, Deputy Permanent and one branch for the ICTR, Representative of the United States of America to the United Nations, chairs a Security Council meeting respectively. The branch of the ICTY ©UN Photo/Paulo Filgueiras shall have its seat in The Hague, The Netherlands. The branch for the The Arusha-based Mechanism shall review the progress of the work of ICTR shall have its seat in Arusha, commence functioning, on 1 July the Mechanism, -

Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Tuesday, 21 June 2011 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Whos’s Special Court Security Chief / Sierra Express Media Page 3 International News 'Ractliffe Judgment Won’t Affect Charles Taylor Case' / Eye Witness News Page 4 Legal Man Robin Loses Cancer Fight / Worcester News Pages 5-6 Former Interahamwe Militia Leader Pleads Not Guilty to Genocide / Hirondelle News Agency Page 7 STL Refuses Comment About End-June Indictment Rumors / The Daily Star Pages 8-9 3 Sierra Express Media Tuesday, 21 June 2011 4 Eye Witness News Tuesday, 21 June 2011 'Ractliffe judgment won’t affect Charles Taylor case' Rahima Essop War crimes accused Charles Taylor’s defence on Monday said Jeremy Ractliffe’s acquittal is significant but will not affect his client’s case in The Hague at this stage. It is alleged the former Liberian leader used blood diamonds to buy weapons and three of those stones ended up in Ractliffe’s possession while he was the head of the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. Last week, the Alexandra Magistrate's Court found Ractliffe not guilty of contravening the Diamond Act. Taylor’s defence counsel Courtenay Griffiths said he has been following events in South Africa with great interest. “Mr. Ractliffe featured in the testimony of Naomi Campbell and it is note worthy that he was in fact acquitted,” he said. -

Rwandan Five Judgment

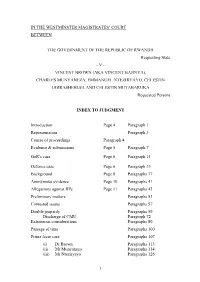

IN THE WESTMINSTER MAGISTRATES’ COURT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA Requesting State - V - VINCENT BROWN (AKA VINCENT BAJINYA), CHARLES MUNYANEZA, EMMANUEL NTEZIRYAYO, CELESTIN UGIRASHEBUJA AND CELESTIN MUTABARUKA Requested Persons INDEX TO JUDGMENT Introduction Page 4 Paragraph 1 Representation Paragraph 3 Course of proceedings Paragraph 4 Evidence & submissions Page 5 Paragraph 7 GoR’s case Page 6 Paragraph 11 Defence case Page 6 Paragraph 33 Background Page 8 Paragraphs 37 Anonymous evidence Page 10 Paragraphs 41 Allegations against RPs Page 11 Paragraphs 43 Preliminary matters Paragraphs 53 Contested issues Paragraphs 57 Double jeopardy Paragraphs 59 Discharge of CMU Paragraph 72 Extraneous considerations Paragraphs 80 Passage of time Paragraphs 100 Prima facie case Paragraphs 107 (i) Dr Brown Paragraphs 113 (ii) Mr Munyaneza Paragraphs 114 (iii) Mr Nteziryayo Paragraphs 126 1 (iv) Mr Ugirashebuja Paragraphs 129 (v) Mr Mutabaruka Paragraphs 136 Section 87 Human Rights Paragraph 137 (i) Article 3 Paragraph 138 Conclusion Paragraphs 147 (ii) Article 6 Paragraphs 150 Brown & others Paragraphs 157 Cases up to 2009 Paragraphs 163 Defence case – summary Paragraph 166 Political situation Paragraph 168 Tables Paragraph 172 Osman warnings Paragraph 197 Experts’ politics Paragraph 205 Conclusions Paragraph 221 Evidence of trials Paragraph 224 Ingabire’s trial Paragraph 231 Conclusions Paragraph 263 Mutabazi’s trial Paragraph 271 Five transfers Paragraph 273 Ahurogeze Paragraph 276 Uwinkindi Paragraph 285 In Rwanda Paragraph -

Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE Chewing bottle!! PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Friday, 31 June 2013 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Africa and The International Criminal Court / PEEP! Pages 3-4 ICC Stretched To Its Limit In Africa / Sierra Express Media Page 5 International News Kenya: Raila Dismisses Race Slur Against ICC / The Star Page 6 International Criminal Tribunal Born as Bastard? / Huffington Post Pages 7-9 When Grave Crimes Elude Justice / The New York Times Pages 10-11 Rwanda: ICTR Last Detainee to Be Transferred Rwanda / The New Times Page 12 3 PEEP! Friday, 31 May 2013 4 5 Sierra Express Media Friday, 31 May 2013 6 The Star Friday, 31 May 2013 Kenya: Raila Dismisses Race Slur Against ICC FORMER Prime Minister Raila Odinga has dismissed accusations of racism levelled against the International Criminal Court by the African Union. Raila described as "hogwash" claims that The Hague court is unfairly targeting African leaders while ignoring war crimes suspects in other parts of the world. "Members of the ICC joined freely, signed the Rome Statute independently which was ratified by their national Parliaments. None was forced to join," he said. The AU on Monday accused the ICC of targeting Africans on the basis of race and called for the termination of criminal proceedings against President Uhuru and Deputy President William Ruto. -

Harris Institute International Council

HARRIS INSTITUTE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL Elizabeth (Betsy) Andersen Betsy Andersen is Executive Director of the World Justice Project, leading its global efforts to advance the rule of law through research, strategic convenings, and support for innovative programs. Ms. Andersen has more than 20 years of experience in the international legal arena, having served previously as Director of the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative (ABA ROLI) and its Europe and Eurasia Division (previously known as the Central European and Eurasian Law Initiative or ABA CEELI), as Executive Director of the American Society of International Law, and as Executive Director of Human Rights Watch’s Europe and Central Asia Division. Ms. Andersen is an expert in international human rights law, international criminal law, and transitional justice, and she has taught these subjects as an adjunct professor at the American University Washington College of Law. She is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and serves as a member of the Board of Trustees of Williams College as well as on the governing and advisory boards of several international non-profit organizations. Ms. Andersen began her legal career in clerkships with Judge Kimba M. Wood of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York and with Judge Georges Abi-Saab of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. The Honorable Louise Arbour The Honorable Louise Arbour recently completed her mandate as the Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General for International Migration. She has also held other senior positions at the United Nations, including High Commissioner for Human Rights (2004- 2008) and Chief Prosecutor for The International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda (1996 to 1999). -

Assembly of States Parties 23 January 2014

International Criminal Court ICC-ASP/12/INF.1 Distr.: General Assembly of States Parties 23 January 2014 English, French and Spanish only Twelfth session The Hague, 20-28 November 2013 [DRAFT] Delegations to the Twelfth session of the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court The Hague, 20-28 November 2013 Délégations présentes à la douzième session de l’Assemblée des États Parties au Statut de Rome de la Cour pénale internationale La Haye, 20-28 novembre 2013 Delegaciones asistentes al duodécimo período de sesiones de la Asamblea de los Estados Partes en el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional La Haya, 20-28 de noviembre de 2013 I1-EFS-230114 ICC-ASP/12/INF.1 Content/ Table des matières/ Índice Page I. States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court/ États Parties au Statut de Rome de la Cour pénale internationale/ Estados Partes en el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional .....................3 II. Observer States/ États observateurs/ Estados observadores................................................................................................31 III. States invited to be present during the work of the Assembly/ Les États invités à se faire représenter aux travaux de l’Assemblée/ Los Estados invitados a que asistieran a los trabajos de la Asamblea.......................39 IV. Entities, intergovernmental organizations and other entities/ Entités, organisations intergouvernementales et autres entités/ Entidades, organizaciones intergubernamentales y otras entidades ..........................41 V. Non-governmental organizations/ Organisations non gouvernementales/ Organizaciones no gubernamentales.........................................................................43 I1-EFS-230114 2 ICC-ASP/12/INF.1 I. States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court/ États Parties au Statut de Rome de la Cour pénale internationale/ Estados Partes en el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional AFGHANISTAN Representative H.E. -

Country Report on Human Rights and Justice in Rwanda

Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs Country Report on Human Rights and Justice in Rwanda Date 18 August 2016 Page 1 of 64 Country Report | August 2016 Edited by Sub-Saharan Africa Department, The Hague Disclaimer: The Dutch version of this report is leading. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands cannot be held accountable for misinterpretations based on the English version of the report. Page 2 of 64 Country Report on Rwanda | August 2016 Contents Contents ....................................................................................................... 3 1 Human Rights .............................................................................................. 6 1.1 Human Rights in General ................................................................................ 6 1.2 Torture and Abuse ....................................................................................... 11 1.2.1 Legislation .................................................................................................. 11 1.2.2 Torture by Military Personnel ......................................................................... 11 1.2.3 Police Abuse ................................................................................................ 13 1.2.4 Local Defence Forces .................................................................................... 13 1.2.5 Monitoring and Assistance ............................................................................. 14 1.3 Disappearances .......................................................................................... -

ICTR NEWSLETTER November 2004

ICTR NEWSLETTER November 2004 Published by the External Relations and Strategic Planning Section – Immediate Office of the Registrar United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda SPECIALSPECIAL EDITIONEDITION International Criminal Tribunal Prosecutors Conclude Conference in Arusha On 27 November, 2004, the Prosecutors also calls upon national and international In This Issue: from the International Criminal Tribunal authorities to assist the tribunals by Joint Statement of the Prosecutors ..................2 for Rwanda (ICTR), the International arresting and transferring indicted fugitives Prosecutor Jallow’s Welcome Address ........2 Criminal Tribunal for the former such as Radovan Karadzic, Ratko Mladic, Challenges of International Criminal Justice .4 Yugoslavia (ICTY), the Special Court for Ante Gotovina, Félicien Kabuga and Challenges of Conducting Investigations of International Crimes ................................................6 Sierra Leone (SCSL) and from the Charles Taylor for trial. General Considerations on the Transfer of International Criminal Court (ICC) Cases and Legal transplants ...............................9 concluded three days of discussions During the three days of meetings in Challenges of International Criminal Justice10 about how to better prepare themselves Arusha, the prosecutors discussed a wide Challenges of the Administration of for meeting the challenges of delivering range of issues they face in bringing to International Criminal Tribunals .......................15 international criminal