Country Report on Human Rights and Justice in Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thematisch Ambtsbericht Over Mensenrechten En Justitie in Rwanda

Thematisch ambtsbericht over mensenrechten en justitie in Rwanda Datum 18 augustus 2016 Pagina 1 van 67 Thematisch ambtsbericht | augustus 2016 Colofon Plaats Den Haag Opgesteld door Directie Sub-Sahara Afrika (DAF) Pagina 2 van 67 Thematisch ambtsbericht | augustus 2016 Inhoudsopgave Colofon ......................................................................................................2 Inhoudsopgave ............................................................................................3 1 Mensenrechten......................................................................................... 6 1.1 Algemene mensenrechtensituatie....................................................................6 1.2 Mishandeling en foltering.............................................................................11 1.2.1 Wetgeving ................................................................................................11 1.2.2 Foltering door militairen ..............................................................................12 1.2.3 Mishandeling door de politie.........................................................................14 1.2.4 Local Defence Forces ..................................................................................14 1.2.5 Toezicht en hulpverlening ............................................................................15 1.3 Verdwijningen ...........................................................................................16 1.4 Buitengerechtelijke executies en moorden......................................................18 -

B-8-2016-1064 EN.Pdf

European Parliament 2014-2019 Plenary sitting B8-1064/2016 4.10.2016 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for a debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 135 of the Rules of Procedure on Rwanda, the case of Victoire Ingabire (2016/2910(RSP)) Charles Tannock, Mark Demesmaeker, Tomasz Piotr Poręba, Ryszard Antoni Legutko, Ryszard Czarnecki, Karol Karski, Anna Elżbieta Fotyga, Arne Gericke, Notis Marias, Angel Dzhambazki, Ruža Tomašić, Monica Macovei, Branislav Škripek on behalf of the ECR Group RE\P8_B(2016)1064_EN.docx PE589.653v01-00 EN United in diversity EN B8-1064/2016 European Parliament resolution on Rwanda, the case of Victoire Ingabire (2016/2910(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to its resolution of 23 May 2013 on Rwanda: case of Victoire Ingabire, – having regard to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, - having regard to the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, - having regard to the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, - having regard to the instruments of the United Nations and the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, in particular the Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa, - having regard to the UN Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or degrading Treatment or Punishment, - having regard to the Cotonou Agreement, – having regard to Rule 135 of its Rules of Procedure, A. whereas Victoire Ingabire in 2010, after 16 years in exile in the Netherlands, President of the Unified Democratic Forces (UDF), a coalition of Rwandan opposition parties, returned to Rwanda to run in the presidential election and was barred from standing in this election against the de facto leader of Rwanda since 1994, Paul Kagame; after the elections was arrested on 14 October 2010; B. -

L'opposante Victoire Ingabire Libérée De Prison

A la une / International Rwanda L'opposante Victoire Ingabire libérée de prison Une des principales figures de l'opposition rwandaise, Victoire Ingabire, est sortie de prison, hier, dans le cadre de la libération anticipée de plus de 2 000 prisonniers décidée la veille par le président Paul Kagame qui dirige son pays d'une main de fer depuis près d'un quart de siècle. “Je remercie le Président qui a permis cette libération”, a dit l'opposante alors qu'elle quittait la prison de Mageragere dans la capitale rwandaise, Kigali. “J'espère que cela marque le début de l'ouverture de l'espace politique au Rwanda”, a-t-elle ajouté, appelant M. Kagame à “libérer d'autres prisonniers politiques”. La libération surprise de 2 140 détenus, dont Mme Ingabire et le chanteur Kizito Mihigo, a été décidée lors d'un conseil des ministres, vendredi, au cours duquel une mesure de grâce présidentielle a été approuvée. “Le conseil des ministres présidé par le président Paul Kagame a approuvé, aujourd'hui, la libération anticipée de 2140 condamnés auxquels les dispositions de la loi leur donnaient droit”, a précisé un communiqué du ministère de la Justice. “Parmi eux figurent M. Kizito Mihigo et Mme Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza, dont le reste de la peine a été commuée par prérogative présidentielle à la suite de leurs dernières demandes de clémence déposées en juin de cette année”, a ajouté le texte. Mme Ingabire avait été arrêtée en 2010 peu de temps après son retour au Rwanda alors qu'elle voulait se présenter à la présidentielle contre Paul Kagame comme candidate du parti des Forces démocratiques unifiées (FDU- Inkingi), une formation d'opposition non reconnue par les autorités de Kigali. -

Open Sainclairthesisfinal.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF AFRICAN STUDIES PROGRAM ETHNIC CONFLICTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION MECHANISMS: A CASE STUDY OF RWANDA TALIA SAINCLAIR SPRING 2016 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in African Studies with honors in African Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Clemente Abrokwaa Professor of African Studies Thesis Supervisor Kevin Thomas Professor of Sociology Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT Conflict forms as an inevitable and fundamental aspect of human nature and coexistence, occurring due to natural differences in human interests, perceptions, desires, ambitions, and general dispositions. Conflict can occur, therefore, based on any range of issues including social, economic, political, cultural and religious beliefs. The purpose of this study is to examine the nature and causes of ethnic conflicts in Africa and the methods employed in resolving such conflicts. Specifically, it focuses on the Rwandan genocide of 1994 and the conflict resolution strategies employed by the government in its attempts at mitigating ethnic tensions in the post-genocide period of the country. The objective is to seek effective methods to help prevent and resolve conflicts on the African continent. Several studies have been conducted on the Rwandan genocide that focus on the conflict itself and its causes, as well as the progress Rwanda has made in the twenty-two years since the end of the genocide. However, few studies have focused on the conflict resolution methods employed in the post- genocide period that enabled the country to recover from the effects of the conflict in 1994 to its current state of peace. -

Rwanda Page 1 of 5

Rwanda Page 1 of 5 Published on Freedom House (https://freedomhouse.org) Home > Rwanda Rwanda Country: Rwanda Year: 2016 Press Freedom Status: Not Free PFS Score: 79 Legal Environment: 23 Political Environment: 34 Economic Environment: 22 Overview Press freedom in Rwanda remained stifled in 2015 as the state continued to assert control over the media. A culture of fear among journalists drives widespread self-censorship. The Rwanda Media Commission (RMC), a fledgling self-regulatory body that had made modest progress in advancing media independence, was hobbled in 2015 by the resignation of its chairman, who fled the country amid tensions between the commission and the Rwandan government. Key Developments • In May, RMC chairman Fred Muvunyi resigned his post and fled the country, saying he had received reports of threats against him after he resisted a government proposal to transfer some of the RMC’s functions to the government’s Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority (RURA). The proposed shift came amid tension between the government and the RMC over the suspension of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Kinyarwanda-language Great Lakes radio service. • Later in May, the RURA announced that it was indefinitely suspending the Great Lakes service, which had been temporarily suspended in October 2014. https://freedomhouse.org/print/48414 5/3/2017 Rwanda Page 2 of 5 • Cassien Ntamuhanga, the head of a Christian radio station, was sentenced in February to 25 years in prison on charges related to an alleged conspiracy against the government. • As in previous years, several opposition blogs and independent news websites were intermittently inaccessible inside Rwanda during 2015. -

The Contribution of the Gacaca Jurisdictions to Resolving Cases Arising from the Genocide Contributions, Limitations and Expecta

The contribution of the Gacaca jurisdictions to resolving cases arising from the genocide Contributions, limitations and expectations of the post-Gacaca phase PRI addresses PRI London First Floor, 60-62 Commercial Street London, E1 6LT. United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7247 6515, Fax: +44 20 7377 8711 E-mail: [email protected] PRI Rwanda BP 370 Kigali, Rwanda Tel.: +250 51 86 64 Fax: +250 51 86 41 [email protected] Web-site address: www.penalreform.org All comments on, and reactions to, this work are welcome. Do not hesitate to contact us at the above addresses. 2 PRI – Final monitoring and research report on the Gacaca process ACKNOWLEDGMENT The year 2009 marked the end of an era for PRI. After years of devoting itself to understanding and analysing the Gacaca jurisdictions, its monitoring and research programme came to a close. Over eight years, PRI travelled across the country in search of facts, people and testimonies; this information formed a series of Gacaca reports which have been published by PRI since 2002. PRI has acquired unique knowledge about the Gacaca jurisdictions and this is largely due to the tenacity, patience, and analytical ability of the Gacaca team in Rwanda. PRI is grateful to all of the men and women who have participated, in whatever way, to the monitoring and research programme on the Gacaca process. PRI takes this opportunity to thank the National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions which participated in and helped the smooth implementation of the programme. Likewise, PRI thanks national and international nongovernmental organizations, which inspired PRI in its work. -

Amended Indictment Acte D'accusation Amende

, INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA ...... ~ Case No. ICTR-96-9-I N de dossier:ICTR-96-9-I THE PROSECUTOR LE PROCUREUR DU TRIBUNAL AGAINST CONTRE LAD ISLAS NTAGANZWA LADISLAS NTAGANZWA AMENDED ACTE D'ACCUSATION INDICTMENT AMENDE The Prosecutor of the International Le Procureur du Tribunal Penal Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, pursuant to International pour Ie Rw"anda, en vertu des the authority stipulated in Atiicle 17 of the pouvoirs que lui confere I'article 17 elu Statute of the International Criminal Statut du Tribunal Penal International pour Tribunal for Rwanda ('the Statute of the Ie Rwanda ("Ie Statut du Tribunal") accuse: Tri b unal ') charges: LADISLAS NTAGANZWA LADISLAS NT AGANZW A with CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT eI'ENTENTE EN VUE DE GENOCIDE, GENOCIDE C9MMETTRE LE GENOCIDE, de COMPLICITY IN GENOCIDE', GENOCIDE de COMPLICITE DE DIRECT AND PUBLIC INCITEMENT GENOCIDE, d'INCITATION TO COMMIT GENOCIDE, CRIMES PUBLIQUE ET DIRECTE A AGAINST HUMANITY, and COMMETTRE LE GENOCIDE, de VIOLATIONS OF ARTICLE 3 CRIMES CONTRE L' HUMANITE, et ele COMMON TO THE GENEVA VIOLATIONS DE L'ARTICLE 3 CONVENTIONS AND ADDITIONAL COMMUN AUX CONVENTIONS DE PROTOCOL II, offences stipulated in GENtVE ET DU PROTOCOLE Articles 2, 3 and 4 of the Statute of the ADDITIONNEL II, crimes prevus aux Tribunal. articles 2, 3 et 4 du Statut du Tribunal. " PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/198713/ 1. CONTEXTE HISTORIQUE 1. HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1. CONTEXTE HISTORIQUE 1.1 The revolution of 1959 marked the 1.1 La revolution de 1959 marque Ie beginning ofa period of ethnic clashes debut d'une periode d'affrontements between the Hutu and the Tutsi in Rwanda, ethniques entre les Hutu et les Tutsi au causing hundreds of Tutsi to die and Rwanda, provoquant au cours des annees thousands more to flee the country in the qui ont immediatement suivi, des centaines years immediately following. -

Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Tuesday, 21 June 2011 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Whos’s Special Court Security Chief / Sierra Express Media Page 3 International News 'Ractliffe Judgment Won’t Affect Charles Taylor Case' / Eye Witness News Page 4 Legal Man Robin Loses Cancer Fight / Worcester News Pages 5-6 Former Interahamwe Militia Leader Pleads Not Guilty to Genocide / Hirondelle News Agency Page 7 STL Refuses Comment About End-June Indictment Rumors / The Daily Star Pages 8-9 3 Sierra Express Media Tuesday, 21 June 2011 4 Eye Witness News Tuesday, 21 June 2011 'Ractliffe judgment won’t affect Charles Taylor case' Rahima Essop War crimes accused Charles Taylor’s defence on Monday said Jeremy Ractliffe’s acquittal is significant but will not affect his client’s case in The Hague at this stage. It is alleged the former Liberian leader used blood diamonds to buy weapons and three of those stones ended up in Ractliffe’s possession while he was the head of the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. Last week, the Alexandra Magistrate's Court found Ractliffe not guilty of contravening the Diamond Act. Taylor’s defence counsel Courtenay Griffiths said he has been following events in South Africa with great interest. “Mr. Ractliffe featured in the testimony of Naomi Campbell and it is note worthy that he was in fact acquitted,” he said. -

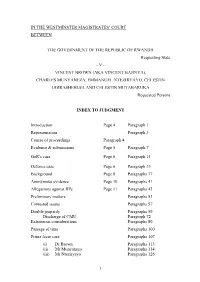

Rwandan Five Judgment

IN THE WESTMINSTER MAGISTRATES’ COURT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA Requesting State - V - VINCENT BROWN (AKA VINCENT BAJINYA), CHARLES MUNYANEZA, EMMANUEL NTEZIRYAYO, CELESTIN UGIRASHEBUJA AND CELESTIN MUTABARUKA Requested Persons INDEX TO JUDGMENT Introduction Page 4 Paragraph 1 Representation Paragraph 3 Course of proceedings Paragraph 4 Evidence & submissions Page 5 Paragraph 7 GoR’s case Page 6 Paragraph 11 Defence case Page 6 Paragraph 33 Background Page 8 Paragraphs 37 Anonymous evidence Page 10 Paragraphs 41 Allegations against RPs Page 11 Paragraphs 43 Preliminary matters Paragraphs 53 Contested issues Paragraphs 57 Double jeopardy Paragraphs 59 Discharge of CMU Paragraph 72 Extraneous considerations Paragraphs 80 Passage of time Paragraphs 100 Prima facie case Paragraphs 107 (i) Dr Brown Paragraphs 113 (ii) Mr Munyaneza Paragraphs 114 (iii) Mr Nteziryayo Paragraphs 126 1 (iv) Mr Ugirashebuja Paragraphs 129 (v) Mr Mutabaruka Paragraphs 136 Section 87 Human Rights Paragraph 137 (i) Article 3 Paragraph 138 Conclusion Paragraphs 147 (ii) Article 6 Paragraphs 150 Brown & others Paragraphs 157 Cases up to 2009 Paragraphs 163 Defence case – summary Paragraph 166 Political situation Paragraph 168 Tables Paragraph 172 Osman warnings Paragraph 197 Experts’ politics Paragraph 205 Conclusions Paragraph 221 Evidence of trials Paragraph 224 Ingabire’s trial Paragraph 231 Conclusions Paragraph 263 Mutabazi’s trial Paragraph 271 Five transfers Paragraph 273 Ahurogeze Paragraph 276 Uwinkindi Paragraph 285 In Rwanda Paragraph -

Samantha Richards Mphil Thesis

Lessons Learnt From Rwanda: The Need for Harmonisation of Penalties Between the ICC and its Member States Samantha Richards MPhil Thesis Student ID: 033365563 Submitted: 30 November 2014 Word count (excluding footnotes): 58,012 Abstract An examination of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its policy of complementarity in the context of the presumption, that for complementarity to be effective, the national courts will have to undertake the majority of the investigations and prosecutions of extraordinary crimes. This will then be discussed in terms of the current setup whereby national courts are permitted by Article 80 of the Rome Statute 1998, to apply their own penalties when conducting trials at the national level. The analysis serves to highlight that the current situation is not conducive to proportionate or consistent sentencing or penalties, as the death penalty may still be applied by national courts, whilst in accordance with human rights norms, the ICC only has custodial sentences available to its judges. In addition to this the discussion highlights that many national jurisdictions where the crimes take place are in need of capacity building so as to rebuild or to reinforce their legal systems to a level where they are able to seek justice for themselves. This leads into a discussion of the potential for outreach whereby the ICC may also be able to lead by example and take the opportunity to impart their sentencing objectives and procedural norms, in an attempt to facilitate consistent and proportionate justice at both the national and international level, so as to aid the fight to close the impunity gap. -

Evidentiary Challenges in Universal Jurisdiction Cases

Evidentiary challenges in universal jurisdiction cases Universal Jurisdiction Annual Review 2019 #UJAR 1 Photo credit: UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata This publication benefted from the generous support of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, the Oak Foundation and the City of Geneva. TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 FOREWORD 8 BUILDING ON SHIFTING SANDS: EVIDENTIARY CHALLENGES IN UNIVERSAL JURISDICTION CASES 11 KEY FINDINGS 12 CASES OF 2018 Argentina 13 VICTIMS DEMAND THE TRUTH ABOUT THE FRANCO DICTATORSHIP 15 ARGENTINIAN PROSECUTORS CONSIDER CHARGES AGAINST CROWN PRINCE Austria 16 SUPREME COURT OVERTURNS JUDGMENT FOR WAR CRIMES IN SYRIA 17 INVESTIGATION OPENS AGAINST OFFICIALS FROM THE AL-ASSAD REGIME Belgium 18 FIVE RWANDANS TO STAND TRIAL FOR GENOCIDE 19 AUTHORITIES ISSUE THEIR FIRST INDICTMENT ON THE 1989 LIBERIAN WAR Finland 20 WAR CRIMES TRIAL RAISES TECHNICAL CHALLENGES 22 FORMER IRAQI SOLDIER SENTENCED FOR WAR CRIMES France ONGOING INVESTIGATIONS ON SYRIA 23 THREE INTERNATIONAL ARREST WARRANTS TARGET HIGH-RANKING AL-ASSAD REGIME OFFICIALS 24 SYRIAN ARMY BOMBARDMENT TARGETING JOURNALISTS IN HOMS 25 STRUCTURAL INVESTIGATION BASED ON INSIDER PHOTOS 26 FIRST IN FRANCE: COMPANY INDICTED FOR CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY 28 FRANCE REVOKES REFUGEE STATUS OF MASS MASSACRE SUSPECT 29 SAUDI CROWN PRINCE UNDER INVESTIGATION 30 INVESTIGATION OPENS ON BENGAZHY SIEGE 3 31 A EUROPEAN COLLABORATION: SWISS NGO SEEKS A WARLORD’S PROSECUTION IN FRANCE 32 IS SELLING SPYING DEVICE TO AL-ASSAD’S REGIME COMPLICITY IN TORTURE? RWANDAN TRIALS IN -

The Adjudication of Genocide: Gacaca and the Road to Reconciliation in Rwanda

SOSNOV_36.2_FINAL 6/5/2008 12:18:12 PM THE ADJUDICATION OF GENOCIDE: GACACA AND THE ROAD TO RECONCILIATION IN RWANDA 1 MAYA SOSNOV INTRODUCTION In 1994, Rwanda suffered one of the worst genocides in history. During 100 days of killing, 800,000 people died.2 More people died in three months than in over four years of conflict in Yugoslavia; moreover, the speed of killing was five times faster than the Nazi execution of the Final Solution.3 Unlike the killings that occurred during the Holocaust, Rwandans engaged in “a populist genocide,” in which many members of society, including children, participated in killing their neighbors with common farm tools (the most popular was the machete).4 While not all Hutus engaged in killing and not all victims were Tutsi, Hutus executed the vast majority of the killings and Tutsis were largely the target of their aggression.5 Fourteen years after the genocide, Rwanda is still struggling with how to rebuild the country and handle the mass atrocities that occurred. During the first four years following the genocide, four types of courts developed to prosecute genocidaires:6 the International Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda, foreign courts exercising universal jurisdiction, domestic criminal courts, and a domestic military tribunal. Regrettably, none of these courts has been able to resolve the enormous problems related to adjudicating genocide suspects. In 2001, the government created gacaca, a fifth system for prosecuting genocidaires, to solve the problems it saw in the other courts. Gacaca is highly lauded by the government and many outside observers as the solution to Rwanda’s genocide.