Rachel Rubin C'17, ” Barbara Strozzi's Feminine Influence on the Cantata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

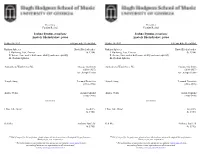

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

Program Notes Scene I

PROGRAM SCENE I NOTES GIOVANNI GIROLAMO KAPSBERGER (C. 1580 – 1651) CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI (1567 – 1643) Toccata arpeggiata Lamento della ninfa While little is known of Kapsberger’s life, he is primarily remembered as a composer As you walk through Venice for the first time, nobody can escape two things: the for theorbo, a large guitar-like instrument that was common in the period. This work, labyrinth of canals, and the striking Piazzo San Marco (St Mark’s Square), which which features on our ARIA award-winning recording Tapas, comes from a beautiful has been walked by countless musical geniuses over the years. One of these was 60-page manuscript published in Venice in 1604, titled Libro primo d'intavolatura di Claudio Monteverdi, who was the head of music at the stunning St Mark’s Basilica chitarrone (first book of theorbo tablature). Tablature is a form of music notation that which dominates the square. Famed for its extraordinary acoustic, St Mark’s indicates fingering rather than specific pitches. In this case, it shows which fingers Basilica was practically Monteverdi’s home, and it was during his over 30 years here are to be placed on which strings of the theorbo. The manuscript below constitutes that he cemented his position as one of the most influential and monumental figures the entirety of the music notated by Kapsberger for this piece: all other aspects in music history. He is usually credited as the father of the opera, and also as the of realising the music are left to the performers. However, the marking arpeggiata most important transitional figure between the Renaissance and Baroque periods indicates that is to be played with arpeggios: musical phrases that take individual of music. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Unsung Heroines, Final Prg AB

The South African Early Music Trust (SAEMT) and Music Mundi present Unsung Heroines Celebrating Barbara Strozzi’s 400th birthday with an all-female Baroque composer’s programme Bianca Maria Meda Cari Musici (1665-1700) for solo soprano, 2 violins & bc Barbara Strozzi Le Tre Gratie (op 1, no 4) (1619-1677) for soprano trio & bc Sonetto proemio del opera: Mercè di voi (op 1, no 1) for soprano duet & bc Il Romeo: Vagò mendico il core (op 2, no 3) - for mezzo-soprano solo & bc Isabella Leonarda Sonata Decima (1620-1704) for two violins & bc Barbara Strozzi Che si può fare (op 8, no 6) for soprano solo & bc Canto di bella bocca (op 1, no 2) for soprano duet & bc – INTERVAL – Francesca Caccini Ciaccona (1587-ca.1641) for solo violin & bc Barbara Strozzi L’eraclito amoroso (op 2, no 14) for soprano solo & bc Dialogo in partenze: Anima del mio core (op 1, no 8) for soprano duet & bc La Riamata da chi Amava: Dormi, dormi (op 2, no 18) for soprano duet, two violins & bc Sino alla morte (op 7, no 1) Cantata for soprano solo & bc Nathan Julius – countertenor, soprano Tessa Roos – mezzo-soprano Antoinette Blyth – soprano & program compilation Annien Shaw, Cornelis Jordaan – Baroque violins Vera Vuković – lute, chitarrone Jan-Hendrik Harvey – Baroque guitar Grant Brasler – virginal Hans Huyssen – Baroque cello & musical direction We thank the Rupert Music Foundation and the Gisela Lange Trust for their generous support, as well as Bill Robson for the use of his virginal. Notes on Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677) Barbara Strozzi had the good fortune to be born into a world of creativity, intellectual ferment, and artistic freedom. -

Radio 3 Listings for 5 – 11 March 2016 Page 1 of 20 SATURDAY 05 MARCH 2016 Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Lukasz Borowicz (Conductor)

Radio 3 Listings for 5 – 11 March 2016 Page 1 of 20 SATURDAY 05 MARCH 2016 Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Lukasz Borowicz (conductor) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b071d0k5) 4:46 AM Nelson Goerner and Dang Thai Son at the 2014 Chopin and his Byrd, William (c.1543-1623) Europe International Music Festival Browning à 5 The Rose Consort of Viols: John Bryan, Alison Crum, Sarah Catriona Young presents a concert given by pianists Nelson Groser, Roy Marks, Peter Wendland (viols) Goerner and Dang Thai Son with the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century in Poland. 4:50 AM Haydn, Joseph (1732-1809) or possibly Pleyel, Ignace 1:01 AM (1757-1831) arr. Perry, Harold Beethoven, Ludwig van [1770-1827] Divertimento (Feldpartita) (H.2.46) in B flat major arr. for wind Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major Op.73 (Emperor) quintet (attributed to Haydn, possibly by Pleyel) Nelson Goerner (piano), Orchestra of the 18th Century, Kenneth Bulgarian Academic Wind Quintet: Georgi Spasov (flute), Georgi Montgomery (conductor) Zhelyazov (oboe), Petko Radev (clarinet), Marin Valchanov (bassoon), Vladislav Grigorov (horn) 1:38 AM Chopin, Fryderyk [1810-1849] 5:01 AM From 24 Preludes Op.28 for piano - No.15 in D flat 'Raindrop' Ebner, Leopold (1769-1830) Nelson Goerner (piano) Trio in B flat major Zagreb Woodwind Trio 1:44 AM Chopin, Fryderyk [1810-1849] 5:08 AM Piano Concerto No.1 in E minor Op.11 Schumann, Robert [1810-1856] Dang Thai Son (piano), Orchestra of the 18th Century, Kenneth Adagio and Allegro in A flat major (Op.70) Montgomery (conductor) Lise Berthaud -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Finding Their Voice: Women Musicians of Baroque Italy

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities English Department 2016 Finding Their Voice: Women Musicians of Baroque Italy Faith Poynor Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_expositor Part of the Musicology Commons Repository Citation Poynor, F. (2016). Finding their voice: Women musicians of Baroque Italy. The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, 12, 70-79. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Their Voice: Women Musicians of Baroque Italy Faith Poynor emale musicians began to achieve greater freedom and indepen- dence from men during the Baroque period, and their music and Fcreative talent consequently began to flourish. Due to the rise in popularity of female vocal ensembles that resulted after the establishment of the con- certo delle donne in 1580, women composers in early modern Italy gained greater access to musical training previously only available to men or nuns. As seen by the works of composers and singers such as Francesca Caccini and Barbara Strozzi, this led to an unprecedented increase in women’s mu- sical productivity, particularly in vocal music. The rise of female vocal ensembles in the early Baroque period was a pivotal moment in women’s music history, as women finally achieved wide- spread recognition for their talents as musicians. -

Il Canto Delle Dame B

IL CANTO DELLE DAME B. STROZZI, F. CACCINI, C. ASSANDRA, I. LEONARDA MARIA CRISTINA KIEHR — JEAN-MARC AYMES — CONCERTO SOAVE Le Centre culturel de rencontre d’Ambronay reçoit le soutien du Conseil général de l’Ain, de la Région Rhône-Alpes et de la Drac Rhône-Alpes. Le label discographique Ambronay Éditions reçoit le soutien du Conseil général de l’Ain. Ce disque a été réalisé avec l’aide de la Région Rhône-Alpes. Concerto Soave reçoit le soutien du ministère de la culture et de la communication (Direction régionale des affaires culturelles de la région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur) au titre de l’aide aux ensembles conventionnés, de la Région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, du Conseil général des Bouches-du-Rhône et de la Ville de Marseille. Il est membre de la FEVIS (Fédération des ensembles vocaux et instrumentaux spécialisés). www.crab-paca.org Remerciements particuliers à Agnès T. Director Alain Brunet Executive Producer for Ambronay Éditions Isabelle Battioni Assistant Charlotte Lair de la Motte Recorded in the abbatial church of Ambronay (France) — 23-26th May 2010 Recording Producer, mixing Tritonus Musikproduktion GmbH, Stuttgart (Germany) Cover photograph & design Benoît Pelletier, Diabolus — www.diabolus.fr Booklet graphic design Ségolaine Pertriaux, myBeautiful, Lyon — www.mybeautiful.fr Booklet photo credits Bertrand Pichène Printers Pozzoli, Italy & © 2010 Centre culturel de rencontre d’Ambronay, 01500 Ambronay, France – www.ambronay.org Made in Europe Tous droits du producteur phonographique et du propriétaire de l'œuvre enregistrée réservés. Sauf autorisation, la duplication, la location, le prêt, l'utilisation de ce disque pour exécution publique et radiodiffusion sont interdits. -

Brünnhilde's Lament: the Mourning Play of the Gods

The Opera Quarterly Advance Access published April 18, 2015 Brünnhilde’s Lament: The Mourning Play of the Gods Reading Wagner’s Musical Dramas with Benjamin’s Theory of Music n sigrid weigel o center for literary and cultural research, berlin It was Brünnhilde’s long, final song in the last scene of Götterdämmerung,in Achim Freyer’s and James Conlon’s Los Angeles Ring cycle of 2010, that prompted me to consider possible correspondences between tragedy and musical drama and, in addition, to ask how recognizing such correspondences affects the commonplace derivation of musical drama from myth1 or Greek tragedy2 and tying Wagner to Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. The impression I had gained from Linda Watson’s rendition of the song did not fit a reading in terms of apotheosis: the way the downfall of the world of the gods is usually staged, when, at the end of the cycle, Brünnhilde kindles the conflagration and follows murdered Siegfried into death. It seemed to me much more that what we heard was a long-extended lament. This performance did not seem to match the prevailing characterization of the scene as “solid and solemn” (fest und feierlich), as Peter Wapnewski has put it, speak- ing of an “apotheotic finale” and a “solemn-pathetic accusation.” In his words, “Now Brünnhilde sings forth the end. In the powerful scene of lonely grandeur that de- mands the singer-actress’s dramatic power to their limits—and beyond.”3 In Freyer’s and Conlon’s Götterdämmerung, tones of lament rather than the pathos of accusa- tion could be heard in Brünnhilde’s final song. -

J. S. Bach's Use of Trombones

J. S. Bach’s Use of Trombones Utilization and Chronology prepared by Thomas Braatz © 2010 J. S. Bach used trombones almost exclusively for cantatas scheduled to be performed on specific Sundays and feast days of the liturgical year beginning with his Estomihi Leipzig audition cantata, BWV 23, performed on February 7, 1723 and ending with BWV 28 for the Sunday after Christmas on December 30, 1725. There are only a few unusual, rather late exceptions to Bach’s usage of trombones, beginning with 1.) a copy (made 1727-1731) of the Kyrie from F. Durante’s Mass in C minor with an indication for 3 trombones (no record of any performance exists); 2.) a transcription of the Kyrie and Gloria of Palestrina’s Missa sine nomine scored for 4 trombones and dated c. 1742 (no record of any performance exists); and including finally 3. a Trauermusik = BWV 118, a single- movement funeral motet composed in 1736/37, originally scored for 2 litui, 1 cornetto, and 3 trombones, but revised later in 1746/47 for a repeat performance but without the trombones, etc. The evidence from the following chronological list of extant cantata materials suggests that there was a limited time-frame of almost three years during which Bach actively utilized trombones for performances of his ‘well-ordered church music’.1 The list includes some well-known cantatas from the pre-Leipzig period, cantatas which originally were not scored for trombones but subsequently were added for performances in Leipzig during this three-year period. The dates listed are for the documented instances when these cantatas using trombones were performed in Leipzig. -

Rejoice in the Lamb Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) This 'Festival Cantata

Rejoice in the Lamb Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) This 'Festival Cantata' for soloists, choir and organ, written in 1943 for the fiftieth anniversary of the consecration of St. Matthew's Church, Northampton, was the first in a celebrated series of commissions by the Rev. Walter Hussey for the church's annual patronal festivals; the series later included, in music, Finzi's Lo, the Full Final Sacrifice and, in other fields of the arts, works by Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and W.H.Auden. At the 1943 celebrations Britten himself conducted the church choir in his new work, sharing the limelight with the Band of the Northamptonshire Regiment performing another festival commission by Michael Tippett. The cantata is a setting of lines selected by Britten from a long poem, Jubilate Agno (over 1200 lines long, in fact – and unfinished) by the ultimately tragic figure of Christopher ('Kitty') Smart (1722-1771), who also wrote as 'Mrs. Midnight' and 'Ebenezer Pentweazle', and was a deeply religious man but, as Hussey himself puts it, "of a strange and unbalanced mind". The poem was in fact written while Smart was confined in an asylum for alleged 'religious mania', and has been seen on the one hand as a vast hymn of praise to God and all his works, and on the other as no more than the ravings of a madman. Published only in 1939, with the subtitle A Song from Bedlam, it was brought to Britten's attention by W.H.Auden. Such a choice of text might seem odd for a jubilee, but there is in the product of such a mind a kind of childlike innocence which in the poet Peter Porter's words "shows the rest of us that heaven does indeed lie about us".