Country Report DOI 10.4119/Jsse-1409

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Europaparlamentet 2019–2024

Europaparlamentet 2019–2024 Utskottet för miljö, folkhälsa och livsmedelssäkerhet ENVI_PV(2020)0305_1 PROTOKOLL från sammanträdet den 5 mars 2020 kl. 9.30–12.30 BRYSSEL Sammanträdet öppnades torsdagen den 5 mars 2020 kl. 9.40 med utskottets ordförande, Pascal Canfin, som ordförande. 1. Godkännande av föredragningslistan ENVI_OJ(2020)0305_1 Föredragningslistan godkändes i den form som framgår av detta protokoll. 2. Meddelanden från ordföranden Ordföranden meddelade följande: Tolkning: Tolkningen motsvarade utskottets normala språkprofil: 21 språk tolkades med undantag för estniska, maltesiska och iriska. Elektroniska sammanträdeshandlingar/webbsändning: Ordföranden informerade om att sammanträdeshandlingar som vanligt fanns tillgängliga i elektroniskt format via programmet för e-sammanträden och att sammanträdet skulle sändas på nätet. Rapport från ad hoc-delegationen till 25:e partskonferensen för FN:s ramkonvention om klimatförändringar i Madrid, Spanien, den 10– 14 december 2019: Ordföranden informerade om att sammanträdeshandlingarna innehöll rapporten från ad hoc-delegationen till 25:e partskonferensen för FN:s ramkonvention om klimatförändringar i Madrid, Spanien, den 10– 14 december 2019. PV\1204450SV.docx PE650.672v01-00 SV Förenade i mångfaldenSV 3. Meddelanden från ordföranden om samordnarnas rekommendationer av den 18 februari 2020 Ordföranden meddelade att samordnarnas rekommendationer av den 18 februari 2020 hade skickats ut elektroniskt, och att de, eftersom inga invändningar lagts fram, ansågs vara godkända (se bilaga -

Print Notify

National Security Bureau https://en.bbn.gov.pl/en/news/462,President-appoints-new-Polish-government.html 2021-09-28, 07:01 16.11.2015 President appoints new Polish government President Andrzej Duda appointed the new Polish government during a Monday ceremony following a sweeping victory of the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) in the October 25 general elections. The president appointed Beata Szydlo as the new prime minister. Following is the line-up of the Beata Szydlo cabinet: Mateusz Morawiecki - deputy PM and development minister Piotr Glinski - deputy PM and culture minister Jaroslaw Gowin - deputy PM and science and higher education minister Mariusz Blaszczak - interior and administration minister fot. E. Radzikowska-Białobrzewska, Antoni Macierewicz - defence minister KPRP Witold Waszczykowski - foreign affairs minister Pawel Szalamacha - finance minister Zbigniew Ziobro - justice minister Dawid Jackiewicz - treasury minister Anna Zalewska - education minister Jan Szyszko - environment minister Elzbieta Rafalska - labour minister Krzysztof Jurgiel - agriculture minister Andrzej Adamczyk - infrastructure and construction minister Konstanty Radziwill - health minister Marek Grobarczyk - maritime economy and inland waterways minister Anna Strezynska - digitisation minister Witold Banka - sports minister Beata Kempa - minister, member of the Council of Ministers, head of PM's Office Elzbieta Witek - minister, member of the Council of Ministers, government spokesperson Henryk Kowalczyk - member of the Council of Ministers, chairman of the Government Standing Committee Mariusz Kaminski - minister, member of the Council of Ministers, coordinator of special services Krzysztof Tchorzewski - member of the Council of Ministers (expected future energy minister) "I feel fully co-responsible for the country's affairs with the prime minister and her government", President Andrzej Duda said Monday at the appointment of Poland's Beata Szydlo government. -

MINISTER Rodziny, Pracy I Polityki Społecznej DF.Y.02101.2.2018.IW

Warszawa, dn. 2018 -06- 0 5 MINISTER Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej DF.Y.02101.2.2018.IW wg rozdzielnika Na podstawie § 35 ust. 1 i 2, § 36 ust. 1, § 40 ust. 2 oraz § 52 uchwały nr 190 Rady Ministrów z dnia 29 października 2013 r. - Regulamin pracy Rady Ministrów (M.P. z 2016 r. poz. 1006, z późn. zm.), zwracani się z prośbą o wyrażenie opinii wobec projektu rozporządzenia Ministra Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej w sprawie przyznawania z Funduszu Pracy środków na podjęcie działalności na zasadach określonych dla spółdzielni socjalnych utworzenie stanowiska pracy w spółdzielni socjalnej oraz na finansowanie kosztów wynagrodzenia skierowanej osoby. Przedmiotowy projekt został udostępniony w Biuletynie Informacji Publicznej na stronie podmiotowej Rządowego Centrum Legislacji, w serwisie Rządowy Proces Legislacyjny. Uwagi proszę przekazać w terminie 14 dni od dnia otrzymania niniejszego pisma także drogą elektroniczną na adres: [email protected] i i oanna.bielinska@mrpi ps. gov .pi. Stanisław Szwed SEKRETARZ STANU Otrzymują: 1. Pan Piotr Gliński, Wiceprezes Rady Ministrów, Minister Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego 2. Pani Beata Szydło, Wiceprezes Rady Ministrów 3. Pan Jarosław Go win, Wiceprezes Rady Ministrów, Minister Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego 4. Pan Andrzej Adamczyk, Minister Infrastruktury 5. Pan Witold Bańka, Minister Sportu i Turystyki 6. Pan Mariusz Błaszczak, Minister Obrony Narodowej 7. Pan Marek Gróbarczyk, Minister Gospodarki Morskiej i Żeglugi Śródlądowej 8. Pan Krzysztof Jurgiel, Minister Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi 9. Pan Joachim Brudziński, Minister Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji 10. Pan Łukasz Szumowski, Minister Zdrowia 11. Pan Teresa Czerwińska, Minister Finansów 12. Pan Henryk Kowalczyk, Minister Środowiska 13. Pan Krzysztof Tchorzewski, Minister Energii 14. -

Poland Daily [email protected]

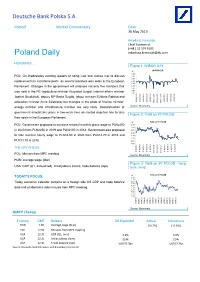

Deutsche Bank Polska S.A. Poland Market Commentary Date 30 May 2019 Arkadiusz KrzeƑniak Chief Economist (+48 ) 22 579 9105 Poland Daily [email protected] HEADLINES… Figure 1: WIBOR O/N % WIBOR O/N 2.20 POL: On Wednesday evening leaders of ruling Law and Justice met to discuss 2.00 1.80 replacements in ministerial posts as several ministers won seats in the European 1.60 1.40 Parliament. Changes in the government will embrace not only five ministers that 1.20 1.00 won seat in the PE (agriculture minister Krzysztof Jurgiel, internal affairs minister 0.80 10/31/2018 11/30/2018 12/31/2018 0.60 5/30/2018 6/30/2018 7/31/2018 8/31/2018 9/30/2018 1/31/2019 2/28/2019 3/31/2019 4/30/2019 Joahim BrudziĔski, deputy MP Beata Szydáo, labour minister ElĪbieta Rafalsa and education minister Anna Zalewska) but changes in the posts of finance minister, energy minister and infrastructure minister are very likely. Reconstruction of Source: Bloomberg government should take place in two-week time as elected deputies has to take Figure 2: Yield on 5Y POLGB their seats in the European Parliament. % Yield on 5Y POLGB POL: Government proposed to increase minimal monthly gross wage to PLN2450 2.70 2.60 in 2020 from PLN2250 in 2019 and PLN2100 in 2018. Government also proposed 2.50 2.40 to hike minimal hourly wage to PLN16.00 in 2020 from PLN14.70 in 2019 and 2.30 2.20 PLN13.70 in 2018. 2.10 2.00 5/30/2018 6/30/2018 7/31/2018 8/31/2018 9/30/2018 10/31/2018 11/30/2018 12/31/2018 1/31/2019 2/28/2019 3/31/2019 4/30/2019 THE DAY AHEAD… POL: Minutes from MPC meeting Source: Bloomberg HUN: average wage (Mar) Figure 3: Yield on 5Y POLGB – long USA: GDP (Q1, annualized), initial jobless claims, trade balance (Apr) term trend % Yield on 5Y POLGB TODAY’S FOCUS: 3.50 3.30 Today economic calendar contains on a foreign side US GDP and trade balance 3.10 2.90 2.70 data and on domestic side minutes from MPC meeting. -

Minister Srodowiska

Warszawa Z015 _03. 0 2 MINISTER SRODOWISKA DP-II.0230.24.2016.MT Wg rozdzielnika Działając na podstawie postanowień uchwały Nr 190 Rady Ministrów z dnia 29 pażdziernika 2013 r. — Regulamin Pracy Rady Ministrów (M.P. poz. 979) uprzejmie informuj ę, że na stronie internetowej Ministerstwa Środowiska pod adresem: htt,s://bi • mos ov.ill)rawo/ ro .ekt «bwieszczen/ został zamieszczony projekt obwieszczenia Ministra Środowiska w sprawie stawek opłat na rok 2017 z zakresu przepisów Prawa geologicznego i górniczego wraz z uzasadnieniem. Uprzejmie proszę o zgłoszenie ewentualnych uwag do ww. projektu w terminie 10 dni od dnia otrzymania niniejszego pisma. Ewentualne uwagi prosz ę przekazywać również drogą elektroniczn ą na adres: [email protected] . Jednocze śnie uprzejmie informuj ę, że brak odpowiedzi w ww. terminie pozwol ę sobie potraktować jako uzgodnienie projektu. z up. xd'f.I~l r.. y. i: [°/;. GLORrN å r Prof Otrzymuj ą: dr h •lu sz - O rio W; yxek 1. Pan Piotr Gliński Wicepremier, Minister Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego 2. Pan Jarosław Gowin Wicepremier, Minister Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego 3. Pan Mateusz Morawiecki Wicepremier, Minister Rozwoju 4. Pan Andrzej Adamczyk Minister Infrastruktury i Budownictwa 5. Pan Witold Bańka Minister Sportu i Turystyki 6. Pan Mariusz Błaszczak Minister Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji 7. Pan Marek Gróbarczyk Minister Gospodarki Morskiej i Żeglugi Śródlądowej 8. Pan Dawid Jackiewicz Minister Skarbu Państwa 9. Pan Krzysztof Jurgiel Minister Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi 10.Pan Antoni Macierewicz Minister Obrony Narodowej 11.Pan Konstanty Radziwiłł Minister Zdrowia 12.Pani Elżbieta Rafalska Minister Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej 13.Pani Anna Streżyńska Minister Cyfryzacj i 14.Pan Paweł Szałamacha Minister Finansów 15.Pan Krzysztof Tchórzewski Minister Energii 16.Pan Witold Waszczykowski Minister Spraw Zagranicznych 17.Pani Anna Zalewska Minister Edukacj i Narodowej 18.Pan Zbigniew Ziobro Minister Sprawiedliwości 19.Pan Mariusz Kamiński Minister — Czlonek Rady Ministrów, Koordynator ds. -

Elżbieta Rafalska

MINISTER Warszawa, dniaj^fgrudnia 2016 Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej Elżbieta Rafalska DPR.IV.02111.3.5.2016.AK2 wg rozdzielnika Na podstawie § 35 ust. 1 uchwały Nr 190 Rady Ministrów z dnia 29 października 2013 r. - Regulamin pracy Rady Ministrów (M. P. z 2016 r. poz. 1006), uprzejmie informuje, Ze na stronie internetowej Ministerstwa Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej w Biuletynie Informacji Publicznej w zakładce Projekty aktów prawnych oraz na stronie podmiotowej Rządowego Centrum Legislacji w serwisie Rządowy Proces Legislacyjny zostd zamieszczony projekt rozporządzenia Ministra Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej zmieniającego rozporządzenie w sprawie bezpieczeństwa i higieny pracy przy pracac i związanych z narażeniem na pole elektromagnetyczne. Jednocześnie uprzejmie informuję, Ze rozporządzenie to musi wejść w życie z dniem 1 stycznia 2017 r. ze względu na konieczność wydłużenia upływającego z dniem 31 grudnia 2016 r. okresu przejściowego, o którym mowa w § 15 nowelizowanego rozporządzenia. W związku z powyższym zwracam się z uprzejmą prośbą o zgłaszanie ewentualnyc i uwag do przedmiotowego projektu w terminie 7 dni od dnia otrzymania niniejszego pisma. Ewentualne uwagi proszę kierować również drogą elektroniczną na adres: [email protected]. Niezgloszenie uwag w tym terminie pozwolę sobie uznać za akceptację projektu. 1. Pani Beata Kempa, Minister - członek Rady Ministrów, Szef Kancelarii Prezesa Racy M inistrów, 2. Pan Henryk Kowalczyk, Minister - członek Rady Ministrów, Przewodniczący Komitet Stałego Rady Ministrów, 3. Pan Mariusz Kamiński, Minister - członek Rady Ministrów, Koordynator Służ Specjalnych, 4. Pani Elżbieta Witek, Minister - członek Rady Ministrów, 5. Pan Piotr Gliński - Wiceprezes Rady Ministrów, Minister Kultury i Dziedzictw Narodowego, 6. Pan Jarosław Gowin - Wiceprezes Rady Ministrów, Minister Nauki i Szkolnictw W yższego, 7. -

1.10.2020 A9-0162/134/Rev Amendment

1.10.2020 A9-0162/134/rev Amendment 134/rev Anna Zalewska, Alexandr Vondra, Ryszard Antoni Legutko, Beata Kempa, Grzegorz Tobiszowski, Beata Mazurek, Kosma Złotowski, Jadwiga Wiśniewska, Andżelika Anna Możdżanowska, Zdzisław Krasnodębski, Joanna Kopcińska, Margarita de la Pisa Carrión, Angel Dzhambazki, Andrey Slabakov, Izabela-Helena Kloc, Zbigniew Kuźmiuk, Elżbieta Kruk, Beata Szydło, Witold Jan Waszczykowski on behalf of the ECR Group Report A9-0162/2020 Jytte Guteland European Climate Law (COM(2020)0080 – COM(2020)0563 – C9-0077/2020 – 2020/0036(COD)) Proposal for a regulation Recital 17 Text proposed by the Commission Amendment (17) As announced in its Communication (17) As announced in its ‘The European Green Deal’, the Communication ‘The European Green Commission assessed the Union’s 2030 Deal’, the Commission assessed the target for greenhouse gas emission Union's 2030 target for greenhouse gas reduction, in its Communication “Stepping emission reduction, in its Communication up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition - "Stepping up Europe's 2030 climate Investing in a climate-neutral future for the ambition - Investing in a climate neutral benefit of our people”9, on the basis of a future for the benefit of our people"9, on comprehensive impact assessment and the basis of a comprehensive impact taking into account its analysis of the assessment and taking into account its integrated national energy and climate analysis of the integrated national energy plans submitted to the Commission in and climate plans submitted to the accordance with Regulation (EU) Commission in accordance with 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the of the Council10. -

1.10.2020 A9-0162/162/Rev Amendment

1.10.2020 A9-0162/162/rev Amendment 162/rev Anna Zalewska, Alexandr Vondra, Ryszard Antoni Legutko, Eugen Jurzyca, Beata Kempa, Jadwiga Wiśniewska, Elżbieta Kruk, Grzegorz Tobiszowski, Kosma Złotowski, Beata Mazurek, Angel Dzhambazki, Andrey Slabakov, Joanna Kopcińska, Andżelika Anna Możdżanowska, Zdzisław Krasnodębski, Margarita de la Pisa Carrión, Izabela-Helena Kloc, Witold Jan Waszczykowski, Zbigniew Kuźmiuk on behalf of the ECR Group Report A9-0162/2020 Jytte Guteland European Climate Law (COM(2020)0080 – COM(2020)0563– C9 0077/2020 – 2020/0036(COD)) Proposal for a regulation Citation 1 Text proposed by the Commission Amendment Having regard to the Treaty on the Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in Functioning of the European Union, and in particular Article 192(1) thereof, particular Articles 192(1) and 194(2) thereof, Or. en AM\P9_AMA(2020)0162(162-168)_REV_EN.docx PE658.338v01-00 EN United in diversityEN 1.10.2020 A9-0162/163/rev Amendment 163/rev Anna Zalewska, Alexandr Vondra, Ryszard Antoni Legutko, Beata Kempa, Jadwiga Wiśniewska, Elżbieta Kruk, Grzegorz Tobiszowski, Kosma Złotowski, Beata Mazurek, Angel Dzhambazki, Andrey Slabakov, Joanna Kopcińska, Andżelika Anna Możdżanowska, Zdzisław Krasnodębski, Margarita de la Pisa Carrión, Izabela-Helena Kloc, Witold Jan Waszczykowski, Zbigniew Kuźmiuk on behalf of the ECR Group Report A9-0162/2020 Jytte Guteland European Climate Law (COM(2020)0080 – COM(2020)0563– C9 0077/2020 – 2020/0036(COD)) Proposal for a regulation Recital 1 Text proposed -

Komunikatzbadań NR 10/2017

KOMUNIKATzBADAŃ NR 10/2017 ISSN 2353-5822 Zaufanie do polityków w styczniu Przedruk i rozpowszechnianie tej publikacji w całości dozwolone wyłącznie za zgodą CBOS. Wykorzystanie fragmentów oraz danych empirycznych wymaga podania źródła Warszawa, styczeń 2017 Znak jakości przyznany CBOS przez Organizację Firm Badania Opinii i Rynku 14 stycznia 2016 roku Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej ul. Świętojerska 5/7, 00-236 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] http://www.cbos.pl (48 22) 629 35 69 ZAUFANIE DO POLITYKÓW W STYCZNIU % Andrzej Duda 59 11 28 2 Beata Szydło 53 13 31 31 Paweł Kukiz 49 19 23 4 5 Zbigniew Ziobro 41 13 39 4 3 Jarosław Kaczyński 37 11 50 3 Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz 36 18 10 4 32 Mateusz Morawiecki 36 14 18 5 27 Jarosław Gowin 35 21 24 6 14 Elżbieta Rafalska 30 13 14 4 39 Mariusz Błaszczak 29 13 29 4 24 Antoni Macierewicz 29 12 51 5 3 Anna Zalewska 27 12 25 5 32 Witold Waszczykowski 26 15 28 4 26 Grzegorz Schetyna 26 22 41 4 6 Ryszard Petru 25 19 41 4 11 Stanisław Karczewski 23 12 16 5 44 Piotr Gliński 22 17 21 4 37 Marek Kuchciński 22 14 30 5 29 Konstanty Radziwiłł 21 14 20 5 39 Włodzimierz Czarzasty 15 19 19 5 41 Zaufanie Obojętność Nieufność Trudno powiedzieć Nieznajomość Badanie „Aktualne problemy i wydarzenia” (320) przeprowadzono metodą wywiadów bezpośrednich (face-to-face) wspomaganych komputerowo (CAPI) w dniach 7–15 stycznia 2017 roku na liczącej 1045 osób reprezentatywnej próbie losowej dorosłych mieszkańców Polski. -

Parlament Europejski

28.5.2021 PL Dziennik Urzędo wy U nii Europejskiej C 203/1 Poniedziałek, 25 listopada 2019 r. IV (Informacje) INFORMACJE INSTYTUCJI, ORGANÓW I JEDNOSTEK ORGANIZACYJNYCH UNII EUROPEJSKIEJ PARLAMENT EUROPEJSKI SESJA 2019-2020 Posiedzenia od 25 do 28 listopada 2019 r. STRASBURG PROTOKÓŁ POSIEDZENIA W DNIU 25 LISTOPADA 2019 R. (2021/C 203/01) Spis treści Strona 1. Wznowienie sesji . 3 2. Otwarcie posiedzenia . 3 3. Oświadczenie Przewodniczącego . 3 4. Zatwierdzenie protokołów poprzednich posiedzeń . 3 5. Komunikaty Przewodniczącego . 3 6. Wnioski o uchylenie immunitetu . 4 7. Skład komisji i delegacji . 4 8. Sprostowania (art. 241 Regulaminu) (dalsze postępowanie) . 4 9. Negocjacje przed pierwszym czytaniem w Parlamencie (art. 71 Regulaminu) (podjęte działania) . 4 10. Podpisanie aktów przyjętych zgodnie ze zwykłą procedurą ustawodawczą (art. 79 Regulaminu) . 5 C 203/2 PL Dziennik Urzędo wy U nii Europejskiej 28.5.2021 Poniedziałek, 25 listopada 2019 r. Spis treści Strona 11. Pytania wymagające odpowiedzi ustnej (składanie dokumentów) . 5 12. Składanie dokumentów . 6 13. Porządek obrad . 8 14. Alarmująca sytuacja klimatyczna i środowiskowa — Konferencja ONZ w sprawie zmiany klimatu w 2019 r. 9 (COP25) (debata) . 15. Przystąpienie UE do konwencji stambulskiej i inne środki przeciwdziałania przemocy ze względu na płeć 10 (debata) . 16. Umowa UE-Ukraina zmieniająca preferencje handlowe w odniesieniu do mięsa drobiowego i przetworów 11 z mięsa drobiowego przewidziane w Układzie o stowarzyszeniu między UE a Ukrainą *** (debata) . 17. Trzydziesta rocznica aksamitnej rewolucji: znaczenie walki o wolność i demokrację w Europie Środkowo- 11 Wschodniej dla historycznego zjednoczenia Europy (debata) . 18. Postępowania wszczęte przez Rosję przeciwko litewskim sędziom, prokuratorom i śledczym prowadzącym 12 dochodzenie w sprawie tragicznych wydarzeń, do których doszło w Wilnie 13 stycznia 1991 r. -

Komunikat Posła Do PE Krzysztofa Jurgiela Po Posiedzeniu

Krzysztof Jurgiel Białystok, dnia 16 maja 2020 r. Poseł do Parlamentu Europejskiego ul. Zwycięstwa 26 C 15 - 703 Białystok Tel. 85 742- 30- 37; 508 801 810 [email protected] Komunikat Prasowy nr 16 z obrad Parlamentu Europejskiego ( 13 – 16 maja 2020 r.) W dniach 13 – 16 maja 2020 r. w Brukseli odbyła się sesja Parlamentu Europejskiego. Podczas sesji podjęto następujące tematy: Wspólna debata - Konkluzje z posiedzenia nadzwyczajnego Rady Europejskiej w dniu 23 kwietnia 2020 r. Oświadczenie Rady i Komisji Europejskiej - Nowe Wspólne Ramy Finansowe, środki własne i plan naprawczy Oświadczenie Rady i Komisji Na początku debaty wystąpił Charles Michel, przewodniczący RE. Oświadczył, że kryzys związany z pandemią COVID-19 jest bezprecedensowy, musimy więc podjąć decyzje bezprecedensowe. Ponad 540 mld euro ma być skierowane na wsparcie miejsc pracy, przedsiębiorstw oraz państw członkowskich. Obecnie szczególnie ważne zadanie – to przywrócenie funkcjonowania rynku wewnętrznego UE. Pandemia nie może anulować ambicji w zakresie cyfryzacji, nadal trzeba walczyć ze zmianami klimatycznymi, stąd aktualność Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu. Unia musi wyciągnąć wnioski z przeszłości, zadbać o strategiczne działy produkcji (m. in. leki, środki ochronne), by były wytwarzane z etykietą „Made in Europe”. Biorąc pod uwagę olbrzymie następstwa kryzysu epidemiologicznego należy wynegocjować ambitny wieloletni budżet (WRF), ale te środki nie wystarczą. Zostanie stworzony Fundusz Naprawczy, aby zmobilizować więcej środków finansowych. Ch. Borel powtarzał: - więcej spójności, konwergencji, integracji, współpracy i solidarności. Wspominając 70. lecie Deklaracji Roberta Schumana wskazał, że podobnie jak zaraz po II wojnie św., Europejczycy wykażą się odwagą, kreacyjnością, aby w dramacie tego kryzysu z energią przeprowadzić odbudowę i transformację europejską. Z kolei zabrała głos Ursula von der Leyen, przewodnicząca KE. -

Protokół Posiedzenia W Dniu 26 Listopada 2019 R. (2021/C 203/02)

28.5.2021 PL Dziennik Urzędo wy U nii Europejskiej C 203/19 Wtorek, 26 listopada 2019 r. PROTOKÓŁ POSIEDZENIA W DNIU 26 LISTOPADA 2019 R. (2021/C 203/02) Spis treści Strona 1. Otwarcie posiedzenia . 25 2. Komunikat Przewodniczącego . 25 3. Przygotowania do posiedzenia Rady Europejskiej w dniach 12-13 grudnia 2019 r. (debata) . 25 4. Wznowienie posiedzenia . 26 5. Uroczyste posiedzenie — Wystąpienie Ołeha Sencowa, laureata Nagrody im. Sacharowa za 2018 r. 26 6. Oświadczenia Przewodniczącego . 26 7. Wznowienie posiedzenia . 26 8. Głosowanie . 27 8.1. Umowa UE-Ukraina zmieniająca preferencje handlowe w odniesieniu do mięsa drobiowego i przetworów z mięsa drobiowego przewidziane w Układzie o stowarzyszeniu między UE 27 a Ukrainą *** (głosowanie) . 8.2. Zmiana zasad dotyczących podatku od wartości dodanej i podatku akcyzowego w odniesieniu 27 do działań obronnych w ramach Unii * (głosowanie) . 8.3. Powołanie Joëlle Elvinger na członka Europejskiego Trybunału Obrachunkowego (głosowanie) . 27 8.4. Powołanie François Rogera-Cazali na członka Trybunału Obrachunkowego (głosowanie) . 28 8.5. Powołanie Alexa Brenninkmeijera na członka Trybunału Obrachunkowego (głosowanie) . 28 8.6. Powołanie Nikolaosa Milionisa na członka Trybunału Obrachunkowego (głosowanie) . 28 8.7. Powołanie Klausa-Heinera Lehnego na członka Trybunału Obrachunkowego (głosowanie) . 28 8.8. Prawa dziecka w związku z 30. rocznicą uchwalenia Konwencji o prawach dziecka (głosowanie) 29 9. Wyjaśnienia dotyczące stanowiska zajętego w głosowaniu . 30 10. Korekty oddanych głosów i zgłoszenia zamiaru oddania głosu . 30 11. Wznowienie posiedzenia . 30 12. Zatwierdzenie protokołu poprzedniego posiedzenia . 30 C 203/20 PL Dziennik Urzędo wy U nii Europejskiej 28.5.2021 Wtorek, 26 listopada 2019 r. Spis treści Strona 13.