Introduction: the Ingredients of a Masterpiece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compassion & Social Justice

COMPASSION & SOCIAL JUSTICE Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo PUBLISHED BY Sakyadhita Yogyakarta, Indonesia © Copyright 2015 Karma Lekshe Tsomo No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the editor. CONTENTS PREFACE ix BUDDHIST WOMEN OF INDONESIA The New Space for Peranakan Chinese Woman in Late Colonial Indonesia: Tjoa Hin Hoaij in the Historiography of Buddhism 1 Yulianti Bhikkhuni Jinakumari and the Early Indonesian Buddhist Nuns 7 Medya Silvita Ibu Parvati: An Indonesian Buddhist Pioneer 13 Heru Suherman Lim Indonesian Women’s Roles in Buddhist Education 17 Bhiksuni Zong Kai Indonesian Women and Buddhist Social Service 22 Dian Pratiwi COMPASSION & INNER TRANSFORMATION The Rearranged Roles of Buddhist Nuns in the Modern Korean Sangha: A Case Study 2 of Practicing Compassion 25 Hyo Seok Sunim Vipassana and Pain: A Case Study of Taiwanese Female Buddhists Who Practice Vipassana 29 Shiou-Ding Shi Buddhist and Living with HIV: Two Life Stories from Taiwan 34 Wei-yi Cheng Teaching Dharma in Prison 43 Robina Courtin iii INDONESIAN BUDDHIST WOMEN IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Light of the Kilis: Our Javanese Bhikkhuni Foremothers 47 Bhikkhuni Tathaaloka Buddhist Women of Indonesia: Diversity and Social Justice 57 Karma Lekshe Tsomo Establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha in Indonesia: Obstacles and -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Konzerte Spielzeit Januar – Juni 2020 20 Jahre

KONZERTE SPIELZEIT JANUAR – JUNI 2020 20 JAHRE NRW-NETZWERK GLOBALER MUSIK BERGKAMEN BIELEFELD BOCHOLT BONN BRILON DETMOLD DÜSSELDORF GELSENKIRCHEN GÜTERSLOH HAMM HERNE KEMPEN KÖLN MESCHEDE MÜNSTER PADERBORN REMSCHEID SIEGEN SOLINGEN WUPPERTAL BRÜSSEL | BELGIEN LEIDEN | NIEDERLANDE KONZERTE JANUAR – JUNI 2020 LEE NARAE PALVAN HAMIDOV 09.01.2020 REMSCHEID 15.04.2020 DÜSSELDORF 10.01.2020 DETMOLD 19.04.2020 PADERBORN 13.01.2020 GÜTERSLOH 20.04.2020 SIEGEN 14.01.2020 HAMM 21.04.2020 HAMM 15.01.2020 DÜSSELDORF 22.04.2020 KÖLN 16.01.2020 WUPPERTAL 23.04.2020 GÜTERSLOH 19.01.2020 SOLINGEN 24.04.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 20.01.2020 SIEGEN 25.04.2020 LEIDEN 22.01.2020 KÖLN 23.01.2020 KEMPEN NIYIRETH ALARCÓN 10.05.2020 PADERBORN LO CÒR DE LA PLANA 11.05.2020 BERGKAMEN 05.02.2020 DÜSSELDORF 13.05.2020 KÖLN 08.02.2020 MESCHEDE 14.05.2020 WUPPERTAL 12.02.2020 GÜTERSLOH 17.05.2020 BRILON 13.02.2020 WUPPERTAL 18.05.2020 SIEGEN 14.02.2020 DETMOLD 19.05.2020 HAMM 16.02.2020 SOLINGEN 20.05.2020 DÜSSELDORF 17.02.2020 SIEGEN 22.05.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 18.02.2020 HAMM 25.05.2020 BOCHOLT 19.02.2020 KÖLN 26.05.2020 HERNE 21.02.2020 BRÜSSEL 27.05.2020 KEMPEN 28.05.2020 REMSCHEID SAFAR 12.03.2020 REMSCHEID TAMALA 13.03.2020 DETMOLD 01.06.2020 DETMOLD 15.03.2020 BRILON 03.06.2020 DÜSSELDORF 16.03.2020 BERGKAMEN 04.06.2020 HERNE 17.03.2020 HAMM 07.06.2020 BONN 18.03.2020 DÜSSELDORF 08.06.2020 BERGKAMEN 19.03.2020 WUPPERTAL 14.06.2020 PADERBORN 21.03.2020 LEIDEN 16.06.2020 HAMM 22.03.2020 PADERBORN 17.06.2020 KÖLN 23.03.2020 BOCHOLT 18.06.2020 WUPPERTAL 24.03.2020 GÜTERSLOH 19.06.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 25.03.2020 KÖLN 20.06.2020 MÜNSTER 26.03.2020 BONN 27.03.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 28.03.2020 BRÜSSEL 29.03.2020 KEMPEN ALLE TERMINE AUCH AUF 31.03.2020 HERNE www.klangkosmos-nrw.de VORWORT Klangkosmos NRW hat Geburtstag! Im Januar 2000 fand das erste Konzert unter dem Label „Klangkosmos“ in Köln statt. -

August 1909) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1909 Volume 27, Number 08 (August 1909) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 27, Number 08 (August 1909)." , (1909). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/550 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUGUST 1QCQ ETVDE Forau Price 15cents\\ i nVF.BS nf//3>1.50 Per Year lore Presser, Publisher Philadelphia. Pennsylvania THE EDITOR’S COLUMN A PRIMER OF FACTS ABOUT MUSIC 10 OUR READERS Questions and Answers on the Elements THE SCOPE OF “THE ETUDE.” New Publications ot Music By M. G. EVANS s that a Thackeray makes Warrington say to Pen- 1 than a primer; dennis, in describing a great London news¬ _____ _ encyclopaedia. A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE THREE MONTH SUMMER SUBSCRIP¬ paper: “There she is—the great engine—she Church and Home Four-Hand MisceUany Chronology of Musical History the subject matter being presented not alpha¬ Price, 25 Cent, betically but progressively, beginning with MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. -

18Th Century Quotations Relating to J.S. Bach's Temperament

18 th century quotations relating to J.S. Bach’s temperament Written by Willem Kroesbergen and assisted by Andrew Cruickshank, Cape Town, October 2015 (updated 2nd version, 1 st version November 2013) Introduction: In 1850 the Bach-Gesellschaft was formed with the purpose of publishing the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) as part of the centenary celebration of Bach’s death. The collected works, without editorial additions, became known as the Bach- Gesellschaft-Ausgabe. After the formation of the Bach-Gesellschaft, during 1873, Philip Spitta (1841-1894) published his biography of Bach.1 In this biography Spitta wrote that Bach used equal temperament 2. In other words, by the late 19 th century, it was assumed by one of the more important writers on Bach that Bach used equal temperament. During the 20 th century, after the rediscovery of various kinds of historical temperaments, it became generally accepted that Bach did not use equal temperament. This theory was mainly based on the fact that Bach titled his collection of 24 preludes and fugues of 1722 as ‘Das wohltemperirte Clavier’, traditionally translated as the ‘Well-Tempered Clavier’ . Based on the title, it was assumed during the 20 th century that an unequal temperament was implied – equating the term ‘well-tempered’ with the notion of some form of unequal temperament. But, are we sure that it was Bach’s intention to use an unequal temperament for his 24 preludes and fugues? The German word for ‘wohl-temperiert’ is synonymous with ‘gut- temperiert’ which in turn translates directly to ‘good tempered’. -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

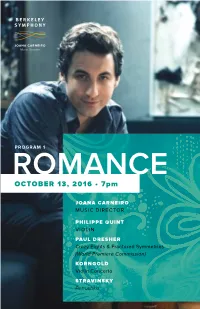

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts Musicianship in Exile: Afghan Refugee Musicians in Finland Facets of the Film Score: Synergy, Psyche, and Studio Lari Aaltonen, University of Tampere Jessica Abbazio, University of Maryland, College Park My presentation deals with the professional Afghan refugee musicians in The study of film music is an emerging area of research in ethnomusicology. Finland. As a displaced music culture, the music of these refugees Seminal publications by Gorbman (1987) and others present the Hollywood immediately raises questions of diaspora and the changes of cultural and film score as narrator, the primary conveyance of the message in the filmic professional identity. I argue that the concepts of displacement and forced image. The synergistic relationship between film and image communicates a migration could function as a key to understanding musicianship on a wider meaning to the viewer that is unintelligible when one element is taken scale. Adelaida Reyes (1999) discusses similar ideas in her book Songs of the without the other. This panel seeks to enrich ethnomusicology by broadening Caged, Songs of the Free. Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience. By perspectives on film music in an exploration of films of four diverse types. interacting and conducting interviews with Afghan musicians in Finland, I Existing on a continuum of concrete to abstract, these papers evaluate the have been researching the change of the lives of these music professionals. communicative role of music in relation to filmic image. The first paper The change takes place in a musical environment which is if not hostile, at presents iconic Hollywood Western films from the studio era, assessing the least unresponsive towards their music culture. -

Read a Complete Transcript of the Interview

In the 1st Person : March 2005 NewMusicBox The Inside Story: Stephen Scott talks with Frank J. Oteri Friday, November 12, 2004—4:30-5:30 p.m. The American Music Center Videotaped by Randy Nordschow Transcribed by Randy Nordschow and Frank J. Oteri Like much of the music I love, Stephen Scott's music first entered my life on an LP. It was over 20 years ago, when I was a DJ at Columbia University's radio station WKCR. Stephen Scott's LP, New Music for Bowed Piano, arrived in the mail with two others—one featuring music by Ingram Marshall, the other by Paul Dresher—all on a record label I had never heard of before called New Albion. In the years since, I've actively followed the careers of all three, both as a listener and someone who writes about music. I've talked with Ingram for NewMusicBox and I've written program notes about Paul Dresher. But, until now, I was never able to verbally catch up with Stephen Scott until he came to visit us at the American Music Center. In some ways, Stephen Scott is the most methodical of these three postminimalist composers who all made minimalism less methodical in very different ways. Not in terms of compositional techniques, but in terms of his sonic vocabulary: all of his work on recordings and most of the music he composes is for his own ensemble of musicians who bow, hammer, scrape, and do any number of other activities inside a grand piano. To this day, aside from this brief video of his piece Entrada, I've never "seen" his music live. -

Flexible Tuning Software: Beyond Equal Temperament

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2011 Flexible Tuning Software: Beyond Equal Temperament Erica Sponsler Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Computer and Systems Architecture Commons, and the Other Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Sponsler, Erica, "Flexible Tuning Software: Beyond Equal Temperament" (2011). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 239. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/239 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Flexible Tuning Software: Beyond Equal Temperament A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Erica Sponsler Candidate for B.S. Degree and Renée Crown University Honors May/2011 Honors Capstone Project in _____Computer Science___ Capstone Project Advisor: __________________________ Dr. Shiu-Kai Chin Honors Reader: __________________________________ Dr. James Royer Honors Director: __________________________________ James Spencer, Interim Director Date:___________________________________________ Flexible Tuning Software: Beyond Equal -

Music and the Making of Modern Science

Music and the Making of Modern Science Music and the Making of Modern Science Peter Pesic The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected]. This book was set in Times by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pesic, Peter. Music and the making of modern science / Peter Pesic. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-02727-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Science — History. 2. Music and science — History. I. Title. Q172.5.M87P47 2014 509 — dc23 2013041746 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Alexei and Andrei Contents Introduction 1 1 Music and the Origins of Ancient Science 9 2 The Dream of Oresme 21 3 Moving the Immovable 35 4 Hearing the Irrational 55 5 Kepler and the Song of the Earth 73 6 Descartes ’ s Musical Apprenticeship 89 7 Mersenne ’ s Universal Harmony 103 8 Newton and the Mystery of the Major Sixth 121 9 Euler: The Mathematics of Musical Sadness 133 10 Euler: From Sound to Light 151 11 Young ’ s Musical Optics 161 12 Electric Sounds 181 13 Hearing the Field 195 14 Helmholtz and the Sirens 217 15 Riemann and the Sound of Space 231 viii Contents 16 Tuning the Atoms 245 17 Planck ’ s Cosmic Harmonium 255 18 Unheard Harmonies 271 Notes 285 References 311 Sources and Illustration Credits 335 Acknowledgments 337 Index 339 Introduction Alfred North Whitehead once observed that omitting the role of mathematics in the story of modern science would be like performing Hamlet while “ cutting out the part of Ophelia. -

Lou Harrison Centennial EVA SOLTES EVA

Please turn off all electronic Photography and audio/video recording devices before entering the in the performance hall are prohibited. performance hall. Lou Harrison Centennial EVA SOLTES EVA DEPARTMENT OF These performances are made possible in part by: PERFORMING ARTS, MUSIC, The P. J. McMyler Musical Endowment Fund AND FILM The Ernest L. and Louise M. Gartner Fund The Cleveland Museum of Art The Anton and Rose Zverina Music Fund 11150 East Boulevard The Frank and Margaret Hyncik Memorial Fund Cleveland, Ohio 44106–1797 The Adolph Benedict and Ila Roberts Schneider Fund The Arthur, Asenath, and Walter H. Blodgett Memorial Fund [email protected] The Dorothy Humel Hovorka Endowment Fund cma.org/performingarts The Albertha T. Jennings Musical Arts Fund #CMAperformingarts Programs are subject to change. Series sponsors: Friday, October 20, 2017 TICKETS 1–888–CMA–0033 cma.org/performingarts Welcome to the PerformingLou Harrison Arts 2017–18 Centennial Cleveland Museum of Art Friday, October 20, 2017, 7:30 p.m. cma.org/performingartsGartner Auditorium, the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Museum of Art’s performing arts series #CMAperformingarts offers a fascinating concert calendar notable for its boundless multiplicity. This year, visits from old friends Chamber Music in the Galleries CIM Organ Studio Wednesday, October 4, 6:00 Sunday, March 11, 2:00 and new bring century-spanning music from around the Mr. Harrison’s Gamelans globe, exploring cultural connections that link the human Butler, Bernstein & the Hot 9 Wu Man & heart and spirit. Wednesday, October 11, 7:30 Huayin Shadow Puppet Band Suite for Violin and Wednesday,Lou Harrison March 21, (1917–2003) 7:30 Lou Harrison Centennial American Gamelan (1973) & Richard Dee In the Galleries Friday, October 20, 7:30 Chamber Music in the Galleries 1.