Dreaming of Virtuosity”: Michael Byron, Dreamers of Pearl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

Russell-Mills-Credits1

Russell Mills 1) Bob Marley: Dreams of Freedom (Ambient Dub translations of Bob Marley in Dub) by Bill Laswell 1997 Island Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance, image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings: Russell Mills 2) The Cocteau Twins: BBC Sessions 1999 Bella Union Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) 3) Gavin Bryars: The Sinking Of The Titanic / Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet 1998 Virgin Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 4) Gigi: Illuminated Audio 2003 Palm Pictures Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Jean Baptiste Mondino 5) Pharoah Sanders and Graham Haynes: With a Heartbeat - full digipak 2003 Gravity Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 6) Hector Zazou: Songs From The Cold Seas 1995 Sony/Columbia Art and design: Russell Mills and Dave Coppenhall (mc2) Design assistance: Maggi Smith and Michael Webster 7) Hugo Largo: Mettle 1989 Land Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance: Dave Coppenhall Photography: Adam Peacock 8) Lori Carson: The Finest Thing - digipak front and back 2004 Meta Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Lori Carson 9) Toru Takemitsu: Riverrun 1991 Virgin Classics Art & design: Russell Mills Cover -

Computer Music Experiences, 1961-1964 James Tenney I. Introduction I Arrived at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in September

Computer Music Experiences, 1961-1964 James Tenney I. Introduction I arrived at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in September, 1961, with the following musical and intellectual baggage: 1. numerous instrumental compositions reflecting the influence of Webern and Varèse; 2. two tape-pieces, produced in the Electronic Music Laboratory at the University of Illinois — both employing familiar, “concrete” sounds, modified in various ways; 3. a long paper (“Meta+Hodos, A Phenomenology of 20th Century Music and an Approach to the Study of Form,” June, 1961), in which a descriptive terminology and certain structural principles were developed, borrowing heavily from Gestalt psychology. The central point of the paper involves the clang, or primary aural Gestalt, and basic laws of perceptual organization of clangs, clang-elements, and sequences (a higher order Gestalt unit consisting of several clangs); 4. a dissatisfaction with all purely synthetic electronic music that I had heard up to that time, particularly with respect to timbre; 2 5. ideas stemming from my studies of acoustics, electronics and — especially — information theory, begun in Lejaren Hiller’s classes at the University of Illinois; and finally 6. a growing interest in the work and ideas of John Cage. I leave in March, 1964, with: 1. six tape compositions of computer-generated sounds — of which all but the first were also composed by means of the computer, and several instrumental pieces whose composition involved the computer in one way or another; 2. a far better understanding of the physical basis of timbre, and a sense of having achieved a significant extension of the range of timbres possible by synthetic means; 3. -

Richard Teitelbaum

RICHARD TEITELBAUM . f lectro-Acoustic Chamber Music February 27-28, 1979 8:30pm $3.50 / $2.00 members / TDF Music The Kitchen Center 484 Broome Street On February 27- 28, The Kitchen Center will present works by Richard Teitel baum. Performers of the compositions and improvisations on the program include George Lewis, trombone and electronics; Reih i Sano, shakuhachi; and Richard Teitel baum, Pol yMoog, MicroMoog and modular Moog synthesizers. The program of electro-acoustic chamber music opens with "Blends," a piece for shakuhachi and synthesizers featuring the playing of Reihi Sano. The piece was composed and first per- formed in 1977, while Teitelbaum was studying in Japan on a Fullbright scholarship. Reihi Sano, who is currently an artist-in-residence at Wesleyan University, has a virtuoso command of the shakuhachi, the endblown bamboo flute. This performance of "Blends" is an American premiere. Similarly, a new work with George Lewis, incorporates Lewis's prodigious com- mand of the trombone and live electronics in a semi-improvisational piece. George Lewis has been involved with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians since 1971, and has played with musicians as diverse as Anth0n.y Braxton, Phil Niblock and Count Basie, in addition to studying philosophy at Yale University. Teitelbaum and Lewis have played at Axis In SoHo, Studio RivBea and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. An extensive synthesizer solo by Teitelbaum, entitled "Shrine" (1976-78) rounds out the concert program. Richard Teitelbaum is one of the prime movers of live electronic music. Classically trained, and with a Master's degree in Music from Yale, he studied in Italy with Luigi Nono. -

Solo Percussion Is Published Ralph Shapey by Theodore Presser; All Other Soli for Solo Percussion

Tom Kolor, percussion Acknowledgments Recorded in Slee Hall, University Charles Wuorinen at Buffalo SUNY. Engineered, Marimba Variations edited, and mastered by Christopher Jacobs. Morton Feldman The King of Denmark Ralph Shapey’s Soli for Solo Percussion is published Ralph Shapey by Theodore Presser; all other Soli for Solo Percussion works are published by CF Peters. Christian Wolff Photo of Tom Kolor: Irene Haupt Percussionist Songs Special thanks to my family, Raymond DesRoches, Gordon Gottlieb, and to my colleagues AMERICAN MASTERPIECES FOR at University of Buffalo. SOLO PERCUSSION VOLUME II WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1578 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2015 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. AMERICAN MASTERPIECES FOR AMERICAN MASTERPIECES FOR Ralph Shapey TROY1578 Soli for Solo Percussion SOLO PERCUSSION 3 A [6:14] VOLUME II [6:14] 4 A + B 5 A + B + C [6:19] Tom Kolor, percussion Christian Wolf SOLO PERCUSSION Percussionist Songs Charles Wuorinen 6 Song 1 [3:12] 1 Marimba Variations [11:11] 7 Song 2 [2:58] [2:21] 8 Song 3 Tom Kolor, percussion • Morton Feldman VOLUME II 9 Song 4 [2:15] 2 The King of Denmark [6:51] 10 Song 5 [5:33] [1:38] 11 Song 6 VOLUME II • 12 Song 7 [2:01] Tom Kolor, percussion Total Time = 56:48 SOLO PERCUSSION WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1578 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. TROY1578 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Sardono Dance Theater and Jennifer Tipton: Rain Coloring Forest

SARDONO DANCE THEATER AND JENNIFER TIPTON: RAIN COLORING FOREST SEPTEMBER 16 – 18, 2010 | 8:30 PM SEPTEMBER 19, 2010 | 3:00 PM presented by REDCAT Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater California Institute of the Arts SARDONO DANCE THEATER AND JENNIFER TIPTON: RAIN COLORING FOREST WORLD PREMIERE Directed, choreographed and performed by Sardono W. Kusumo Artwork by Sardono W. Kusumo Lighting Designed by Jennifer Tipton Original music composed and performed by David Rosenboom Digital Projections by Maureen Selwood Dance and vocals Bambang “Besur” Suryono Dancer I Ketut Rina Assistant lighting designer Iskandar K. Loedin Animation assistants Meejin Hong and Joanna Leitch Produced by REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater) Rain Coloring Forest Managing Producer: Laura Kay Swanson Production Crew: Ernie Mondaca, Israel Mondaca, Patrick Traylor, Tiffany Williams Special thanks to The Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia in Los Angeles , Mr. Arifin Panigoro, Astra Price, Nathan Ruyle and Linda Wissmath. Rain Coloring Forest is made possible by the Contemporary Art Centers (CAC) network, administered by the New England Foundation for the Arts (NEFA), with major support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. CAC is comprised of leading art centers, and brings together performing arts curators to support collaboration and work across disciplines, and is an initiative of NEFA’s National Dance Project. BIOGRAPHIES Sardono W. Kusumo (Director and Choreographer) has been acclaimed as one of the most cutting- edge contemporary choreographers and brilliant theatrical imagists of Asia, even at the beginning of his artistic career. He has been credited by Michel Cournot of Le Monde (Paris) as the creator of the five most captivating yet silent minutes of the Festival Mondiale at the Théâtre de Nancy (1973). -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

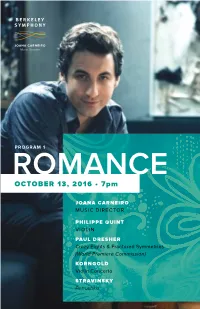

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

EV16 Inner DP

16 extreme voice JohnJJohnohn FoxxFoxx Exploring an Ocean of possibilities Extreme Voice 16 : Introduction All text and pictures © Extreme Voice 1997 except where stated. 1 Reproduction by permission only. have please. , g.uk . ears in My Eyes Cerise A. Reed [email protected] , oice Dancing with T obinhar r and eme V Extr hope you’ll like it! The Gift http://www.ultravox.org.uk , e ris, URL: has just been finished, and should be in the shops in June. EMAIL (ROBIN): Monument g.uk Rage In Eden enewal form will be enclosed. Cheques etc payable to (0117) 939 7078 We’ll be aiming for a Christmas issue, though of course this depends on news and events. We’ll Cerise Reed and Robin Har [email protected] UK £7.00 • EUROPE £8.00 • OUTSIDE EUROPE £11.00 as follows: It’s been an exceptionally busy year for us, what with CD re-releases and Internet websites, as you’ll been an exceptionally busy year for us, what with CD re-releases It’s TEL / FAX: THIS YEAR! 19 SALISBURY STREET, ST GEORGE, BRISTOL BS5 8EE ENGLAND STREET, 19 SALISBURY best! ”, and a yellow subscription r y eatment. At the time of writing EV16 EMAIL (CERISE): ry them, or at least be able to order them. So far ry them, or at least be able to order essages to the band, chat with fellow fans, download previously unseen photographs, listen to messages from Midge unseen photographs, listen to messages from essages to the band, chat with fellow fans, download previously ee in the following pages. -

Worldnewmusic Magazine

WORLDNEWMUSIC MAGAZINE ISCM During a Year of Pandemic Contents Editor’s Note………………………………………………………………………………5 An ISCM Timeline for 2020 (with a note from ISCM President Glenda Keam)……………………………..……….…6 Anna Veismane: Music life in Latvia 2020 March – December………………………………………….…10 Álvaro Gallegos: Pandemic-Pandemonium – New music in Chile during a perfect storm……………….....14 Anni Heino: Tucked away, locked away – Australia under Covid-19……………..……………….….18 Frank J. Oteri: Music During Quarantine in the United States….………………….………………….…22 Javier Hagen: The corona crisis from the perspective of a freelance musician in Switzerland………....29 In Memoriam (2019-2020)……………………………………….……………………....34 Paco Yáñez: Rethinking Composing in the Time of Coronavirus……………………………………..42 Hong Kong Contemporary Music Festival 2020: Asian Delights………………………..45 Glenda Keam: John Davis Leaves the Australian Music Centre after 32 years………………………….52 Irina Hasnaş: Introducing the ISCM Virtual Collaborative Series …………..………………………….54 World New Music Magazine, edition 2020 Vol. No. 30 “ISCM During a Year of Pandemic” Publisher: International Society for Contemporary Music Internationale Gesellschaft für Neue Musik / Société internationale pour la musique contemporaine / 国际现代音乐协会 / Sociedad Internacional de Música Contemporánea / الجمعية الدولية للموسيقى المعاصرة / Международное общество современной музыки Mailing address: Stiftgasse 29 1070 Wien Austria Email: [email protected] www.iscm.org ISCM Executive Committee: Glenda Keam, President Frank J Oteri, Vice-President Ol’ga Smetanová,