Conference Program 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title 11Th Street Waltz Sean Mcgowan Sean

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title Title Creator(s) Arranger Performer Month Year 101 South Peter Finger Peter Finger Mar 2000 11th Street Waltz Sean McGowan Sean McGowan Aug 2012 1952 Vincent Black Lightning Richard Thompson Richard Thompson Nov/Dec 1993 39 Brian May Queen May 2015 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover Paul Simon Paul Simon Jan 2019 500 Miles Traditional Mar/Apr 1992 5927 California Street Teja Gerken Jan 2013 A Blacksmith Courted Me Traditional Martin Simpson Martin Simpson May 2004 A Daughter in Denver Tom Paxton Tom Paxton Aug 2017 A Day at the Races Preston Reed Preston Reed Jul/Aug 1992 A Grandmother's Wish Keola Beamer, Auntie Alice Namakelua Keola Beamer Sep 2001 A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bob Dylan Bob Dylan Dec 2000 A Little Love, A Little Kiss Adrian Ross, Lao Silesu Eddie Lang Apr 2018 A Natural Man Jack Williams Jack Williams Mar 2017 A Night in Frontenac Beppe Gambetta Beppe Gambetta Jun 2004 A Tribute to Peador O'Donnell Donal Lunny Jerry Douglas Sep 1998 A Whiter Shade of Pale Keith Reed, Gary Brooker Martin Tallstrom Procul Harum Jun 2011 About a Girl Kurt Cobain Nirvana Nov 2009 Act Naturally Vonie Morrison, Johnny Russel The Beatles Nov 2011 Addison's Walk (excerpts) Phil Keaggy Phil Keaggy May/Jun 1992 Adelita Francisco Tarrega Sep 2018 Africa David Paich, Jeff Porcaro Andy McKee Andy McKee Nov 2009 After the Rain Chuck Prophet, Kurt Lipschutz Chuck Prophet Sep 2003 After You've Gone Henry Creamer, Turner Layton Sep 2005 Ain't It Enough Ketch Secor, Willie Watson Old Crow Medicine Show Jan 2013 Ain't Life a Brook -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2019). The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1). In: Dodd, R. (Ed.), Writing to Louis Andriessen: Commentaries on life in music. (pp. 83-101). Eindhoven, the Netherlands: Lecturis. ISBN 9789462263079 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/22291/ Link to published version: Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1) Ian Pace Introduction Assumptions of over-arching unity amongst composers and compositions solely on the basis of common nationality/region are extremely problematic in the modern era, with great facility of travel and communications. Arguments can be made on the bases of shared cultural experiences, including language and education, but these need to be tested rather than simply assumed. Yet there is an extensive tradition in particular of histories of music from the United States which assume such music constitutes a body of work separable from other concurrent music, or at least will benefit from such isolation, because of its supposed unique properties. -

PROBES #2 Devoted to Exploring the Complex Map of Sound Art from Different Points of View Organised in Curatorial Series

Curatorial > PROBES With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes PROBES #2 devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points of view organised in curatorial series. All the ‘normal’ music we listen to is out of tune, especially when it’s ‘in tune’. Curated by Chris Cutler, PROBES takes Marshall McLuhan’s So, should music be in harmony with the laws of physics, or adjusted to fit the conceptual contrapositions as a starting point to analyse and wishful thinking of stave notation? expose the search for a new sonic language made urgent after the collapse of tonality in the twentieth century. The series looks at the many probes and experiments that were 01. Summary launched in the last century in search of new musical resources, and a new aesthetic; for ways to make music In the late nineteenth century two facts conspired to change the face of music: adequate to a world transformed by disorientating the collapse of common practice tonality (which overturned the certainties technologies. underpinning the world of Art music), and the invention of a revolutionary new form of memory, sound recording (which redefined and greatly empowered the Curated by Chris Cutler world of popular music). A tidal wave of probes and experiments into new musical resources and new organisational practices ploughed through both disciplines, bringing parts of each onto shared terrain before rolling on to underpin a new PDF Contents: aesthetics able to follow sound and its manipulations beyond the narrow confines 01. Summary of ‘music’. This series tries analytically to trace and explain these developments, 02. -

Newslist Drone Records 31. January 2009

DR-90: NOISE DREAMS MACHINA - IN / OUT (Spain; great electro- acoustic drones of high complexity ) DR-91: MOLJEBKA PVLSE - lvde dings (Sweden; mesmerizing magneto-drones from Swedens drone-star, so dense and impervious) DR-92: XABEC - Feuerstern (Germany; long planned, finally out: two wonderful new tracks by the prolific german artist, comes in cardboard-box with golden print / lettering!) DR-93: OVRO - Horizontal / Vertical (Finland; intense subconscious landscapes & surrealistic schizophrenia-drones by this female Finnish artist, the "wondergirl" of Finnish exp. music) DR-94: ARTEFACTUM - Sub Rosa (Poland; alchemistic beauty- drones, a record fill with sonic magic) DR-95: INFANT CYCLE - Secret Hidden Message (Canada; long-time active Canadian project with intelligently made hypnotic drone-circles) MUSIC for the INNER SECOND EDITIONS (price € 6.00) EXPANSION, EC-STASIS, ELEVATION ! DR-10: TAM QUAM TABULA RASA - Cotidie morimur (Italy; outerworlds brain-wave-music, monotonous and hypnotizing loops & Dear Droners! rhythms) This NEWSLIST offers you a SELECTION of our mailorder programme, DR-29: AMON – Aura (Italy; haunting & shimmering magique as with a clear focus on droney, atmospheric, ambient music. With this list coming from an ancient culture) you have the chance to know more about the highlights & interesting DR-34: TARKATAK - Skärva / Oroa (Germany; atmospheric drones newcomers. It's our wish to support this special kind of electronic and with a special touch from this newcomer from North-Germany) experimental music, as we think its much more than "just music", the DR-39: DUAL – Klanik / 4 tH (U.K.; mighty guitar drones & massive "Drone"-genre is a way to work with your own mind, perception, and sub bass undertones that evoke feelings of total transcendence and (un)-consciousness-processes. -

The History of Rock Music - the 2000S

The History of Rock Music - The 2000s The History of Rock Music: The 2000s History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2006 Piero Scaruffi) Bards and Dreamers (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Bards of the old world order TM, ®, Copyright © 2008 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Traditionally, the purposefulness and relevance of a singer-songwriter were defined by something unique in their lyrical acumen, vocal skills and/or guitar or piano accompaniment. In the 1990s this paradigm was tested by the trend towards larger orchestrastion and towards electronic orchestration. In the 2000s it became harder and harder to give purpose and meaning to a body of work mostly relying on the message. Many singer-songwriters of the 2000s belonged to "Generation X" but sang and wrote for members of "Generation Y". Since "Generation Y" was inherently different from all the generations that had preceeded it, it was no surprise that the audience for these singer-songwriters declined. Since the members of "Generation X" were generally desperate to talk about themselves, it was not surprising that the number of such singer- songwriters increased. The net result was an odd disconnect between the musician and her or his target audience. The singer-songwriters of the 2000s generally sounded more "adult" because... they were. -

THE ROCK IS STILL ROLLING FINAL.Pdf

‘THE ROCK IS STILL ROLLING’: CAMUS’ ABSURDITY AND THE MUSIC OF SATIE NIMISHI ILANGO MA by Research University of York Music December 2016 It is nigh on impossible to find examples of musicological scholarship that have correlated Western art music to the philosophical concept of absurdity as theorised by Albert Camus. Erik Satie’s music has characteristics that can be related to aspects of absurdity, despite pre- dating Camus’ theory. Much of the theory of absurdity will come from Camus’ extended essay entitled The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), which delineates his thinking on absurdity as part of the human condition: essentially that life is rendered meaningless by its unceasing, repetitive cycles. My thesis will focus on two of Satie’s works in relation to absurdity, Socrate and Vexations. Their characteristic features, such as repetition and immobility, bear a striking resemblance to the corresponding plays of the Theatre of the Absurd. The term for this category of plays and their grouping was coined by Martin Esslin, whose comparison of absurdity to another art form has been invaluable in the formulation of my own methodology. Whilst Satie may not have written in a consciously absurd way, ultimately I aim to reveal that a new and illuminating reading of Satie’s music can be generated through the lens of absurdity. LIST OF CONTENTS Abstract 2 List of Contents 3 List of Musical Examples 4 Acknowledgements 6 Declaration 7 Chapter 1: Introduction 8 Chapter 2: Absurdity 18 Chapter 3: Socrate 38 Chapter 4: Vexations 82 Chapter 5: Conclusion -

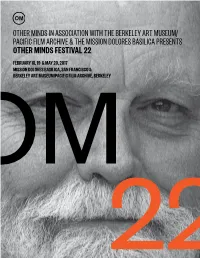

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings. -

Kalvos & Damian: the Car Guys of New Music

“Kalvos & Damian: The Car Guys of New Music” A Presentation to the Colloquium at Wesleyan University, March 29, 2018 Dennis Báthory-Kitsz From 1995 to 2008, two composers going by the pseudonyms “Kalvos” and “Damian” hosted an eponymous radio show. It became the first new music show online in the U.S., where they interviewed more than 350 composers in the studio and on road trips, set up 48 on-air concerts including a full opera with a cast of 40, arranged the first trans- Atlantic internet/radio simulcast between Vermont and the Netherlands, put on a major new music festival with 37 concerts in one weekend, held a two-day international composer combat, and won international recognition including the prestigious ASCAP/Deems Taylor Award—and they did it entirely on small contributions and by a wacky, seat-of-their-pants imagination. And in 2010, they disappeared after 560 programs. Who were they? Why did they do it? What happened to them? Here is the story of “Kalvos & Damian”—the “Car Guys” of new music. Kalvos & Damian’s New Music Bazaar BACKGROUND—BECAUSE THINGS ARE SO COMPLICATED Background on us: David Gunn and I are both lifelong composers. We always took our work seriously, but not our attitudes toward new art and music and its pretensions. I was Project Director for an arts group in Trenton, New Jersey, that gave concerts and festivals of unusual material, from 1973-1978. The largest was the Delaware Valley Festival of the Avant-Garde, modeled after Charlotte Moorman’s annual New York Avant-Garde Festival, where I had played every year. -

A Sweeter Music Preben Antonsen (B.1991) Dar Al-Harb: House of War * Polansky (B’Midbar) No

Cal Performances Presents Program Sunday, January 25, 2009, 3pm The Residents drum no fife (Why We Need War) * Hertz Hall Polansky (B’midbar) No. 6 * A Sweeter Music Preben Antonsen (b.1991) Dar al-Harb: House of War * Polansky (B’midbar) No. 14 * Sarah Cahill, piano Mamoru Fujieda (b.1952) The Olive Branch Speaks John Sanborn, video Terry Riley (b.1935) Be Kind to One Another (Rag) * Commissioned by Stephen B. Hahn and Mary Jane Beddow. PROGRAM * World Premiere Peter Garland (b.1952) After the Wars (excerpts) * Sarah Cahill would like to thank the following individuals: 1. “The nation is ruined, but mountains and Dorothy Cahill, Robert Cole, Miranda Sanborn, Liz and Greg Lutz, Robert Bielecki, rivers remain” (Tu Fu) Margaret Dorfman, Steve Hahn and Mary Jane Beddow, Jerry Kuderna, Paul Dresher, 2. “Summer grass/all that remains/ Joshua Raoul Brody, Skip Sweeney, Bonnie Hughes, Dave Jones Design, Margaret Cromwell, of young warriors’ dreams” (Basho) Joseph Copley and, most of all, John Sanborn, the collaborator and partner of my dreams. Larry Polansky (b.1953) (B’midbar) No. 1 * Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Frederic Rzewski (b.1938) Peace Dances * Commissioned by Robert Bielecki. Polansky (B’midbar) No. 17 * Education & Community Event Yoko Ono (b.1933) Toning * Composers Forum: The Music of Peace: Can Music Be Political? Friday, January 23, 2009, 6–7:30pm Jerome Kitzke (b.1955) There Is a Field * Wheeler Auditorium 1. I Sarah Cahill and several of the commissioned composers discuss the intersection 2. Look Down Fair Moon of politics and music, especially in works without text, and what it means to write 3.